27 October 2020

There are artists who do not stop producing masterpieces in their old age. Instead of diminishing, their creative energy intensifies. Titian, Bellini, Rembrandt, Degas, Manet, Picasso, Cy Twombly: they all had great endgames, but it is the fortune of a very few. The French critic and publisher Tériade showed that he was well aware of this when, at the beginning of the seventies, he told his friend Henri Cartier-Bresson: “You have done all that you could do in photography…. You have said all that you had to say, and you have nothing more to prove. You would not be able to go as far, and then you would stumble, repeat yourself and become fossilized. You should go back to painting and drawing.”1 The photographer, who had just turned sixty (he was born in 1908) and was already considered a living monument of contemporary photography, took his advice and in 1974 hung up his Leica and brought to a close the glorious career that had earned him the title of “eye of the century.” He really did devote himself to drawing, returning every so often, up until 1980, to take the odd portrait on commission.

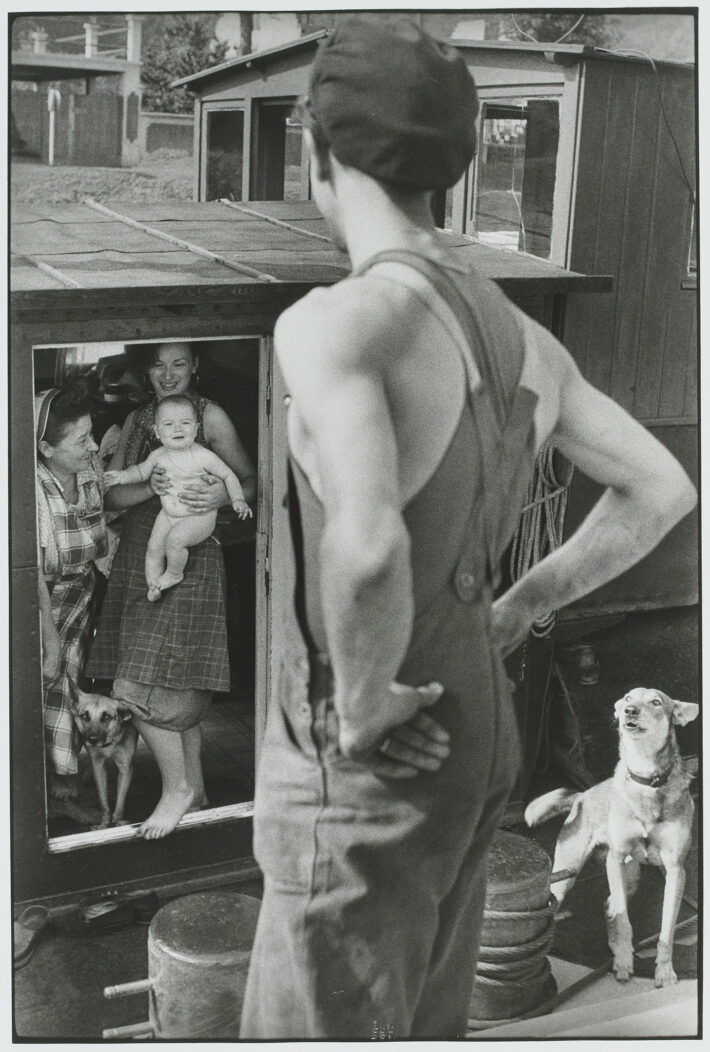

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Bougival, France, 1956, épreuve gélatino-argentique de 1973 © Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson / Magnum Photos.

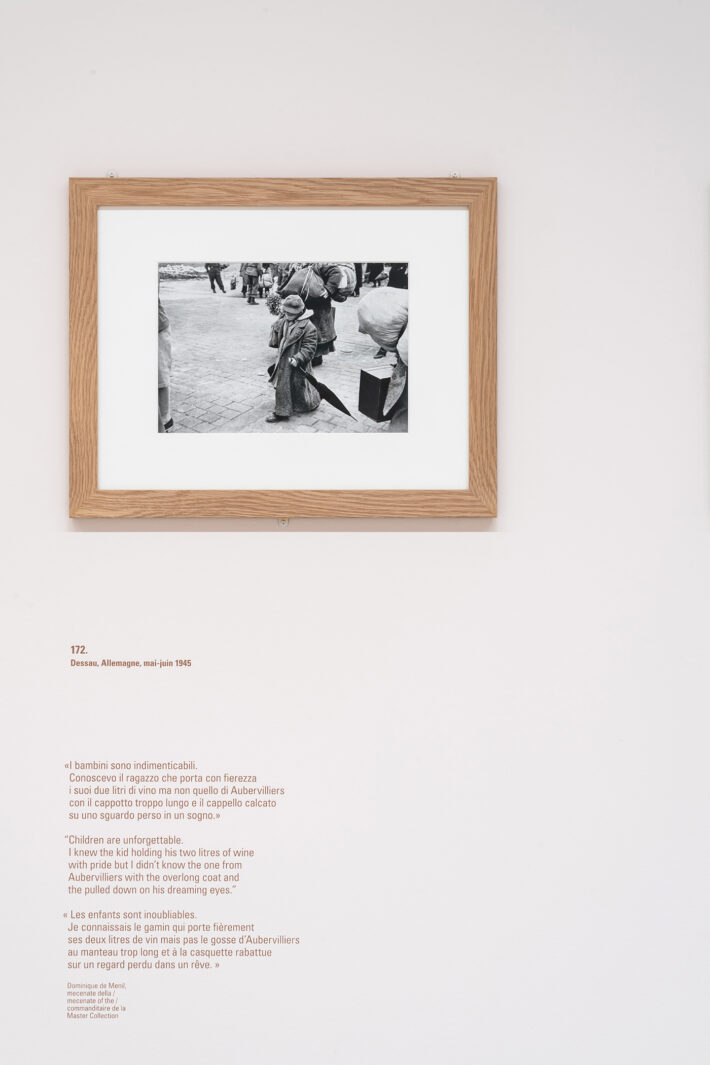

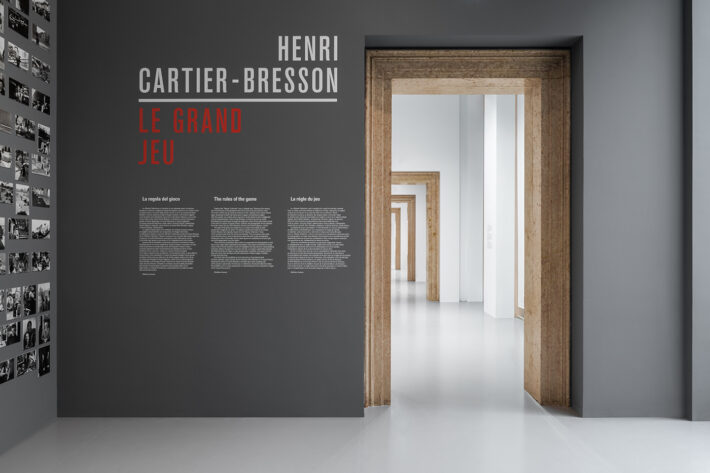

It was in this period, when it was already clear that his work as a photographer was a thing of the past, that the request arrived from the collectors and patrons of the arts John and Dominique de Menil to make a selection of the best of his output. It was an opportunity for HCB to take stock of that work and draw up what is today considered a true artistic testament. And thus the Master Collection was born, or Le Grand Jeu, as the photographer’s friends called it: 385 gelatin silver prints, all measuring 30×40 centimeters, made by George Fèvre at his Parisian lab Pictorial, following the precise instructions of the photographer, and stored in five boxes. Six sets were produced, and are now in the Menil Collection in Houston, at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris, at the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson and at the University of Osaka, in Japan. The last of the six has recently been acquired by the Pinault Collection, which until March 20, 2021, will be showing these images at Palazzo Grassi in an exhibition divided into five different sections. The title is Le Grand Jeu and refers not just to the unofficial title of the Master Collection but also to the game in which five different curators have been invited to take part. The rules of this game, drawn up by Matthieu Humery, who has coordinated the operation, are simple: the participants have been asked to pick fifty pictures out of the ones chosen by Cartier-Bresson. None of them was aware of the choices made by the other curators. Each was free to choose the setting, the color of the walls and the style of the frames. The players were the master of the house, the collector François Pinault, the photographer Annie Leibovitz, the film director Wim Wenders, the writer Javier Cercas and the conservator and director of the Department of Prints and Photography of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France Sylvie Aubenas.

In the exhibition, the pictures are accompanied by brief texts (and in Wenders’s case by a video too) excerpted from the longer essays in the catalogue published by Marsilio. The show, which occupies the entire second floor of the palazzo facing onto the Grand Canal, does not, therefore, present the whole of the Master Collection (which is, however, reproduced in its entirety at the end of the catalogue), but offers us different takes on a corpus of images of which, moreover, Cartier-Bresson never made clear the criteria on which they were selected. There is no chronological order, there is no rigorous geographical subdivision, there is no, to a casual observer, connection between themes that would justify the sequence. And yet, as Jean-François Chevrier has written: “We should take seriously the fact that an artist who photographs is not just a person who takes pictures. He can also be someone who composes an overarching discourse on the basis of his own images, who assembles them and gives them a sense as a whole.”2 To say what is the sense of this sequence is to say who HCB was and what vision he had of the world. It is what the many critics who have written of him have tried to do. But the impression that one gets, after seeing this exhibition, is that the material from which the five curators made their choice is so vast and rich that they were able to see their own reflections in it, offering visitors what is certainly a personal portrait of Cartier-Bresson, but also, and perhaps above all, a picture of themselves.

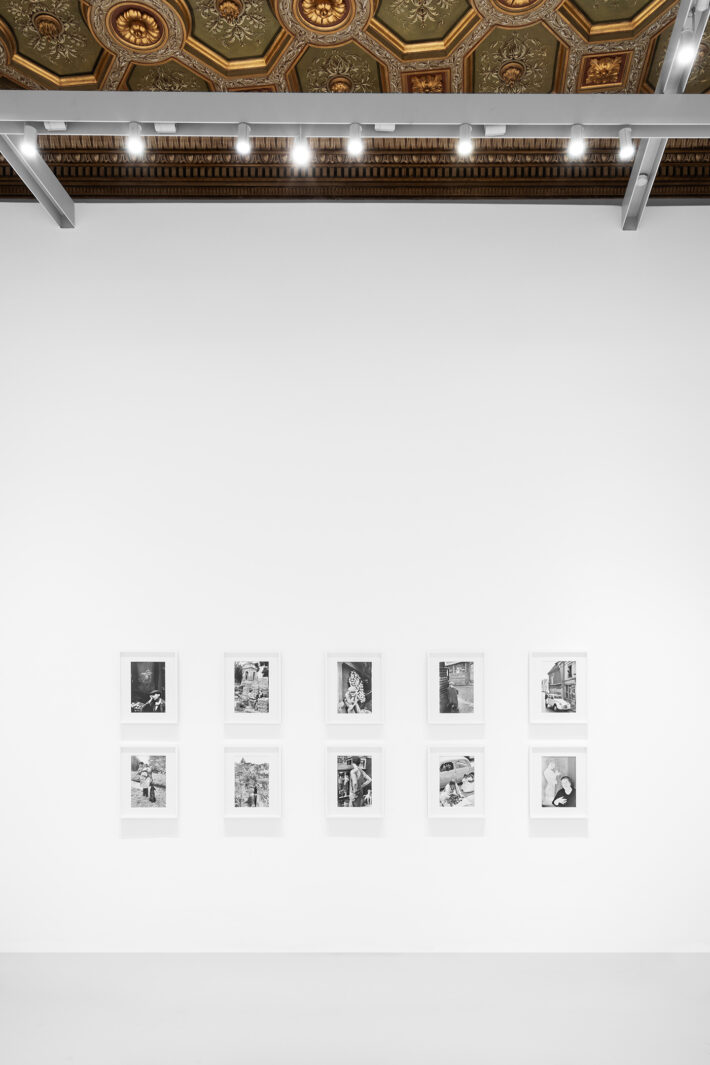

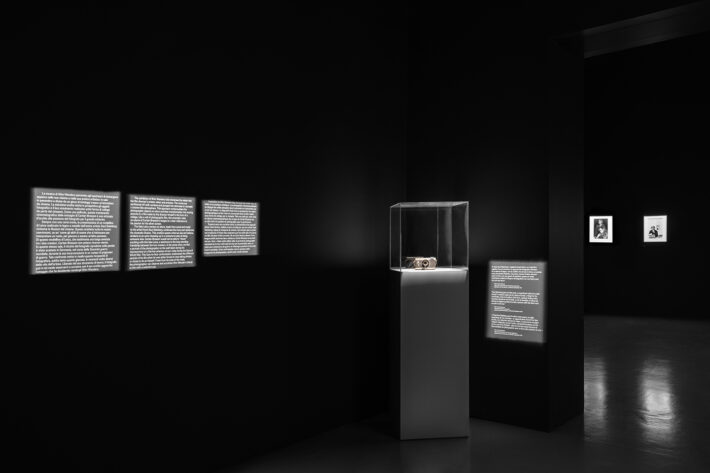

Works by Henri Cartier-Bresson, installation view Henri Cartier-Bresson. Le Grand Jeu at Palazzo Grassi, 2020 © Palazzo Grassi. Photo: Marco Cappelletti.

Those who are familiar with HCB’s work will find the great classics, like Dimanche sur le bords de Seine (1938), Derrière la gare Saint-Lazare (1932) and the portraits of Matisse, Giacometti and Beckett. But they will also find less well-known and no less surprising images. Going back to Cartier-Bresson today, even when we think we have already digested and assimilated him, is an experience that obliges us to reflect again on what we think photography is and the way in which we have chosen to look at the world. “I believe that a collection, or in any case the one that I have built and continue to enrich, aims to hold on to the ineluctable passage of time. The works and the dialogue created between them are the expression of life itself, its dynamism and passion. Cartier-Bresson is an artist who shows us the furtive, comical, and familiar aspects of life.”3 This is how François Pinault explains, in a few words, the sense of his being a collector, his desire to acquire the Master Collection and the criteria on which he made his selection for the exhibition. The images are divided into four sections: Happy Days, The Happenstance of Daily Life, Strangeness in the Street and Portraits. “Truth, simplicity, humility: that is what characterizes the work of Cartier-Bresson in my eyes,” continues the collector: “That is what I wanted to try to reflect in the choices I have made. Undoubtedly, there is a link with my love of minimalist art. I love the fact that a lot is said with a minimum of means.”4

On the other hand Annie Leibovitz, presenting her selection, confesses first of all that it was precisely the encounter with HCB’s photographs that made her want to become a photographer. “I was a young painting student at the San Francisco Art Institute when I looked at The World of Henri Cartier-Bresson, which had just been published. Maybe it was something about the word ‘world,’ as well as the pictures, that seduced me. The idea that a photographer could travel with a camera to different places, see how other people lived, make looking a mission—that that could be your life was an amazing, thrilling idea.”5 Leibovitz’s discourse, in reality, focuses on two pictures that are not in the exhibition. One is the portrait that Cartier-Bresson made of Susan Sontag, her partner in life, in 1972. “Susan sat on a couch with a coat wrapped around her because she was cold. Cartier-Bresson sat on a chair opposite her with his camera in his lap. They talked for a few minutes and every now and then she would hear a click. He never brought the camera to his eye.”6 For the photographer, the result is one of the most beautiful portraits of Sontag, which succeeded in capturing her intelligence and charisma. A photograph, however, that HCB did not include in the Master Collection and so could not be presented in Le Grand Jeu.

Works by Henri Cartier-Bresson, installation view Henri Cartier-Bresson. Le Grand Jeu at Palazzo Grassi, 2020 © Palazzo Grassi. Photo: Marco Cappelletti.

But the other picture is the one that she herself tried to take of the great photographer. She asked him for an appointment, but got no answer. So she went to see him at the Magnum office in Paris and succeeded in having lunch with him. But HCB was categorical: no interview, no photograph. Annie did not sleep that night. She went back the next day and waited for him on a bridge that she knew he would cross on his way to the agency and, when she saw him, started to take pictures from a distance. When he realized what was going on, he hid his face with his hat and started yelling: “How could you do this?” She had betrayed his trust. Then he calmed down and said: “If you’re going to take my picture,” he said, “take a good one.” At that point he allowed Leibovitz to take a few shots. Afterward, he confided to her that “he didn’t want to be photographed because he felt that he wouldn’t be able to do his work on the street if people knew what he looked like. They would behave differently.” So Leibovitz never published that picture.

For the Spanish writer Javier Cercas, the door into the world of the French photographer is through literature. The four sections into which his section is divided are introduced by portraits of four of his heroes: Ezra Pound, Albert Camus, William Faulkner and Samuel Beckett. Each of them represents one of the aspects that Cercas considers characteristic of the HCB’s work. The first is that in many of these photographs the essential part seems to be located outside the frame. We are made aware of this by the effect it has on the people in the picture. The second aspect, he explains, is “the dreamlike intensification of reality,”7 a legacy of the time Cartier-Bresson spent in Surrealist circles in his youth. The third is the element of violence, linked to war and revolution. The last is the element of Spanish reality, which the writer underlines by including in the exhibition film clips that HCB shot during the Spanish Civil War. Looking at Cartier-Bresson’s images, Cercas asks himself: “Can art be reporting without falling into chaos and without ceasing to be art? Can art be a form of reporting and reporting be a form of art? And isn’t all of this an oxymoron?”8 For the writer the best answer to these questions can be found in the photographs, which embody the concept of which HCB has become the symbol: the “decisive moment.” Cercas observes: “It is not about retouching reality, using its chaos to construct a form that reality itself does not possess—that is what art has always done, and it is what the photographer Irving Penn did, for example, if we want to mention one of Cartier-Bresson’s contemporaries—but rather to discover an order and a signification, or an illusion of signification in the ‘formless’ magma of reality, and wait until it is captured, like catching a fly in midflight.”9

Works by Henri Cartier-Bresson, installation view Henri Cartier-Bresson. Le Grand Jeu at Palazzo Grassi, 2020 © Palazzo Grassi. Photo: Marco Cappelletti.

When you enter the section curated by Wim Wenders it is like going into a movie theater. In the darkness, Cartier-Bresson’s pictures are skillfully illuminated and look like projections of the frames of a film. As well as a great storyteller, the German director is an outstanding photographer and combines his expertise (on a technical level as well) with a capacity to see and explain what it is that he finds striking in HCB’s work. One of the photographs he has selected is the picture—taken in 1948 in Srinagar, India—of a group of women viewed from behind, in traditional dress, gazing from an elevation at the plain and the mountains on the horizon. “It even seems that the woman standing tall in the center is explaining to the others the splendor in front of their eyes (and ours). Her gesture seems to say: ‘Look at that! What majesty!’”10 But Wenders, reflecting on this image, asks himself who is the man that at that moment has lifted the Leica to his eye and taken the shot? Certainly, he is the person who has made himself the go-between for the message passed on by the Indian woman. But the director adds that he can see something else: “The desire to be that connection is so great that I can physically feel how much the man behind this camera wants to disappear himself, just wants to become the instrument, the link, the messenger for the union that is taking place in front of him. We become part of this act of veneration and devotion, of holiness and sanctity that these women seem to sense and implore. This photograph is all about this message, not about the messenger.”11 In Wenders’ eyes, Cartier-Bresson—i.e. the man present in the invisible reverse angle of these photographs—is a person of great modesty and humanity. Characteristics that are palpable in all the pictures. But that is not all. For the director each photograph carries the most revolutionary message of the 20th century, a message that that he imagines runs more or less as follows: “You are free, we are equals, we are brothers and sisters. And what I happen to be doing here, this thing called photography, is the perfect tool to spread that message. But don’t think I think higher of myself, just because I’m the one holding the camera. We share LIFE, which is so much more than mere photography.”12

Works by Henri Cartier-Bresson, installation view Henri Cartier-Bresson. Le Grand Jeu at Palazzo Grassi, 2020 © Palazzo Grassi. Photo: Marco Cappelletti.

The task of bringing the route through the exhibition to an end has fallen to Sylvie Aubenas, who as a scholar does not hide her embarrassment at having to say something about the work that, ever since the time of the exhibition at the MoMA in New York curated by Beaumont Newhall in 1947, has been dissected by the most important critics of photography: from Michel Frizot to Pierre Assouline and from Jean-François Chevrier to Agnès Sire and Peter Galassi. And so Aubenas declares that what she is showing with her selection is, before everything else, her Cartier-Bresson. The section opens with the theme of light, followed by those of children, movement, black and white (“I find emotion in black-and-white: it transposes, it is an abstraction, it is not ‘normal’”13), the arrangement of figures in space, the theme of the double and, finally, portraits. To explain his popularity, even among the laity, the scholar quotes something Claude Cookman said: “What makes Cartier-Bresson’s photography so rich and equally so apt in sparking off contradictory interpretations is that it combines the formal qualities and the accessibility of the contents to a degree that very few contemporaries have managed to achieve.”14 Certainly, HBC’s refinement of gaze, feeling for form and artistic ambition come from his early education and from his frequentation of the exponents of Surrealism in Paris. When he showed at the MoMA at the age of thirty-nine he seemed to moving toward art photography. But it was Robert Capa who gave him the advice that would change his life and, probably, help him to go down in history: “Beware of labels. They are comforting, but people will stick them on to you and you will never be able to get rid of them. You will be labeled like the little surrealist photographer… you will be lost, and will become precious and mannered. Continue on your way, but with the label of photojournalist, and keep the rest deep in your heart.”15

Henri Cartier-Bresson. Le Grand Jeu

Curated by Matthieu Humery

Palazzo Grassi, Venice

July 11, 2020 – March 20, 2021

Works by Henri Cartier-Bresson, installation view Henri Cartier-Bresson. Le Grand Jeu at Palazzo Grassi, 2020 © Palazzo Grassi. Photo: Marco Cappelletti.

Works by Henri Cartier-Bresson, installation view Henri Cartier-Bresson. Le Grand Jeu at Palazzo Grassi, 2020 © Palazzo Grassi. Photo: Marco Cappelletti.

Works by Henri Cartier-Bresson, installation view Henri Cartier-Bresson. Le Grand Jeu at Palazzo Grassi, 2020 © Palazzo Grassi. Photo: Marco Cappelletti.

Works by Henri Cartier-Bresson, installation view Henri Cartier-Bresson. Le Grand Jeu at Palazzo Grassi, 2020 © Palazzo Grassi. Photo: Marco Cappelletti.

Works by Henri Cartier-Bresson, installation view Henri Cartier-Bresson. Le Grand Jeu at Palazzo Grassi, 2020 © Palazzo Grassi. Photo: Marco Cappelletti.

Works by Henri Cartier-Bresson, installation view Henri Cartier-Bresson. Le Grand Jeu at Palazzo Grassi, 2020 © Palazzo Grassi. Photo: Marco Cappelletti.

Works by Henri Cartier-Bresson, installation view Henri Cartier-Bresson. Le Grand Jeu at Palazzo Grassi, 2020 © Palazzo Grassi. Photo: Marco Cappelletti.

Works by Henri Cartier-Bresson, installation view Henri Cartier-Bresson. Le Grand Jeu at Palazzo Grassi, 2020 © Palazzo Grassi. Photo: Marco Cappelletti.

Works by Henri Cartier-Bresson, installation view Henri Cartier-Bresson. Le Grand Jeu at Palazzo Grassi, 2020 © Palazzo Grassi. Photo: Marco Cappelletti.

Works by Henri Cartier-Bresson, installation view Henri Cartier-Bresson. Le Grand Jeu at Palazzo Grassi, 2020 © Palazzo Grassi. Photo: Marco Cappelletti.

Works by Henri Cartier-Bresson, installation view Henri Cartier-Bresson. Le Grand Jeu at Palazzo Grassi, 2020 © Palazzo Grassi. Photo: Marco Cappelletti.

Works by Henri Cartier-Bresson, installation view Henri Cartier-Bresson. Le Grand Jeu at Palazzo Grassi, 2020 © Palazzo Grassi. Photo: Marco Cappelletti.

Works by Henri Cartier-Bresson, installation view Henri Cartier-Bresson. Le Grand Jeu at Palazzo Grassi, 2020 © Palazzo Grassi. Photo: Marco Cappelletti.

Works by Henri Cartier-Bresson, installation view Henri Cartier-Bresson. Le Grand Jeu at Palazzo Grassi, 2020 © Palazzo Grassi. Photo: Marco Cappelletti.

Works by Henri Cartier-Bresson, installation view Henri Cartier-Bresson. Le Grand Jeu at Palazzo Grassi, 2020 © Palazzo Grassi. Photo: Marco Cappelletti.

Works by Henri Cartier-Bresson, installation view Henri Cartier-Bresson. Le Grand Jeu at Palazzo Grassi, 2020 © Palazzo Grassi. Photo: Marco Cappelletti.

Works by Henri Cartier-Bresson, installation view Henri Cartier-Bresson. Le Grand Jeu at Palazzo Grassi, 2020 © Palazzo Grassi. Photo: Marco Cappelletti.

Notes

1 Pierre Assouline, Henri Cartier-Bresson: A Biography (London: Thames & Hudson, 2005), 225.

2 Jean-François Chevrier, “Henri Cartier-Bresson / Walker Evans: Photographier l’Amérique, 1929-1947,” in Revoir Henri Cartier-Bresson, ed. Anne Cartier-Bresson and Jean-Pierre Montier (Paris: Textuel, 2009), 180.

3 François Pinault, Henri Cartier-Bresson. Le Grand Jeu (Venice: Marsilio, 2020), 38.

4 Pinault, Henri Cartier-Bresson. Le Grand Jeu, 39.

5 Annie Leibovitz, Henri Cartier-Bresson. Le Grand Jeu, 73.

6 Leibovitz, Henri Cartier-Bresson. Le Grand Jeu, 74.

7 Javier Cercas, Henri Cartier-Bresson. Le Grand Jeu, 104.

8 Cercas, Henri Cartier-Bresson. Le Grand Jeu, 105.

9 Ibidem.

10 Wim Wenders, Henri Cartier-Bresson. Le Grand Jeu, 154.

11 Ibidem.

12 Wenders, Henri Cartier-Bresson. Le Grand Jeu, 155.

13 “Nul ne peut entrer ici s’il n’est pas géomètre,” interview with Yves Bourde, Le Monde, September 5, 1974, 13. Published in English as “Only Geometricians May Enter,” in Henri Cartier-Bresson: Interviews and Conversations 1951-1998, ed. Clément Chéroux and Julie Jones (New York: Aperture, 2017), 66.

14 Claude Cookman, “L’Artiste et le reporter: variation sur un sujet,” in De qui s’agit-il? ed. Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Delpire and Jean-Noël Jeanneney (Paris: Gallimard, 2004), 396.

15 Assouline, Henri Cartier-Bresson: A Biography, 142