23 September 2021

Jason Fulford has blue eyes and smiles a lot. He never loses his cool. He is courteous, patient and never makes obvious remarks. Last June, at the opening of his exhibition at Micamera in Milan entitled Picture Summer on Kodak Film, like the monograph published by Mack in 2020, he was wearing a camouflage mask in red, green, blue and pink and clutching a blue Frisbee. Fulford is one of the most interesting figures in the world of American photography: he has an effervescent mind, is cultured and boasts a great sense of humor. He is a book designer, publisher (he founded J&L Books in 2000), and as has brought out ten or so books of his own photography (the most famous are Raising Frogs for $$$, The Mushroom Collector and Hotel Oracle). He has been awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship and his pictures have appeared in The Atlantic, Harper’s, The New Yorker, The New York Times and The New York Times Magazine. His latest effort is Photo No-Nos (Aperture, 2021), a book in which he has asked artists, publishers, critics and curators for their taboos in photography. There are contributions from, among others, Joel Meyerowitz, Vince Aletti, Nadav Kander, Alec Soth, Duane Michals, Mark Steinmetz, Alex Webb, Taryn Simon, John Gossage and Guido Guidi. The result is a surprising book that gives a list of over a hundred and fifty subjects which, according to some, ought not to be photographed. It runs from the A of Abandoned Buildings to the Z of Zoom Screenshot. At C, among other things, we find Current & Political Topics. At P there are even Pickup Trucks. At S, A Shoe Left Behind After a Disastrous Event. For Y there’s Yakuza. An intriguing theme that, as Fulford says in the introduction, despite being “framed in terms of negatives,” highlights “the reasons why people are motivated to make pictures.” This is the door that we have used to enter the strange world of Jason Fulford.

Photo No-Nos: Meditations on What Not to Photograph, a cura di Jason Fulford, copertina, © Aperture, 2021.

Where did the idea for this book come from?

I’ve been discussing this with friends and colleagues for some time. Among photographers it’s quite common to talk about of which are our clichés or our best shots. Reflecting on this sort of thing is part of the artistic process: it’s normal to think about your own work and ask other people for their reactions. And it’s a fact: there are pictures that you start to take and go on doing it, while other images lose their interest. The point is to understand why.

What did you ask your colleagues?

Very simple questions: “Are there things that tell yourself not to photograph?” “Is there anything you’ve never photographed?” “What have you stopped photographing?” “What rule have you set yourself and then broken?”

Is it an instruction book?

No, not at all. The approach is not dogmatic, and it doesn’t tell the reader what is right to photograph and what is not. There was a generation of teachers who gave their students lists of subjects to avoid; they did it with the best intentions, to get them to understand that they could take more interesting pictures than the usual stereotypes, but now things have changed. Even artists don’t think like that anymore, they don’t set themselves creative, stylistic or linguistic limits. Making this book has largely been a matter of listening to the stories and experiences of each one of them.

How did you choose the names?

I started with photographers I knew personally. Then, during the first lockdown, I also contacted young photographers whom I’d never met, looking for them in areas where my work had never taken me. I passed whole days on the internet studying the work of new authors.

Why do you think that this “negative” approach might render the theme interesting?

The first time I proposed this book to Aperture was six or seven years ago. They agreed to publish it, but then it was me who chose to give up the project because the subject, even just thinking about it, had a negative effect on me.

In what sense?

It had literally paralyzed me. Every time I took a photograph I asked myself whether it was right or not to do so. I asked myself the question obsessively: will it be too contrived, too sentimental or perhaps even too beautiful? It went on like this for months and at a certain point I said to myself that I couldn’t do this book.

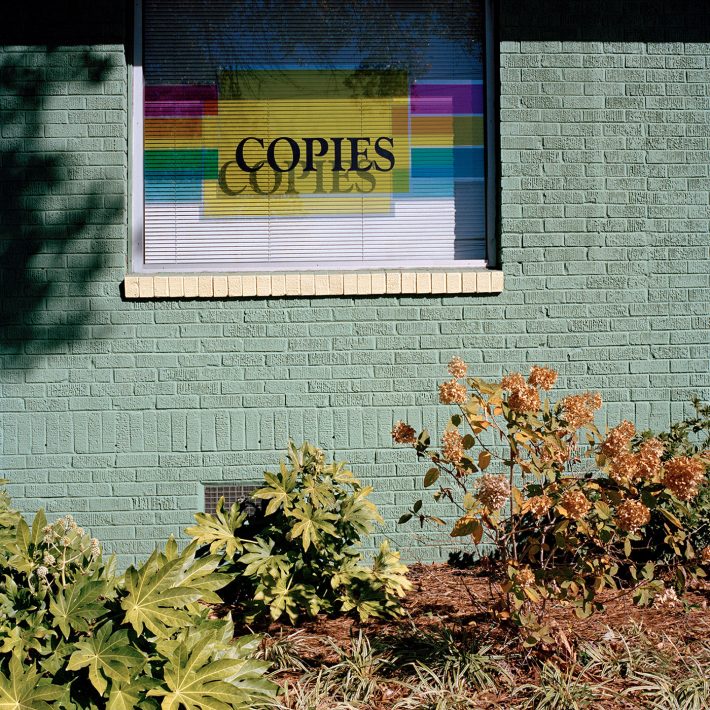

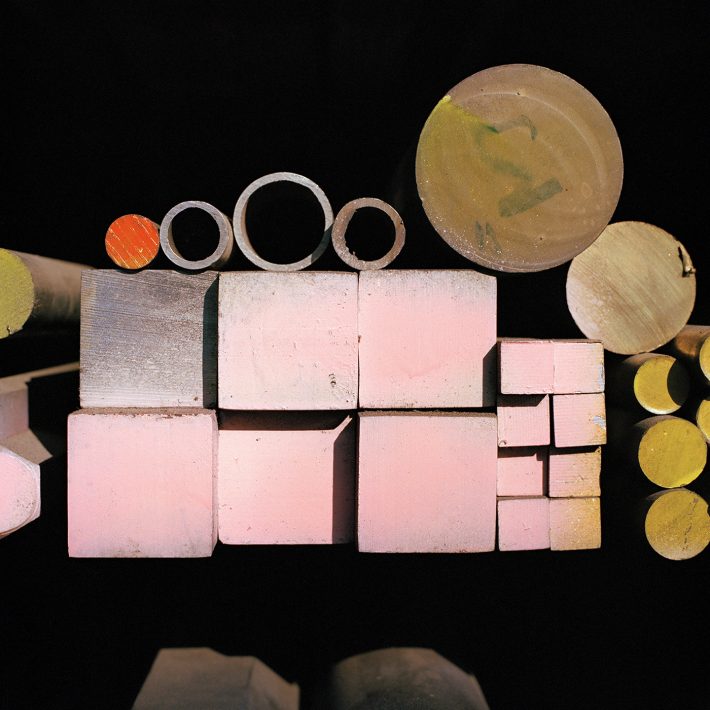

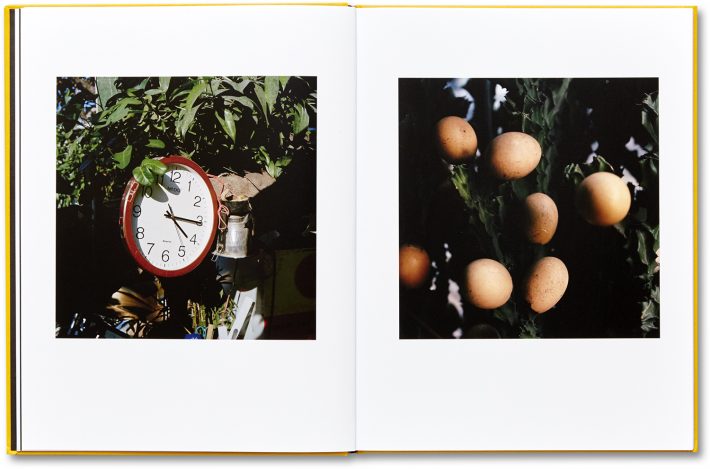

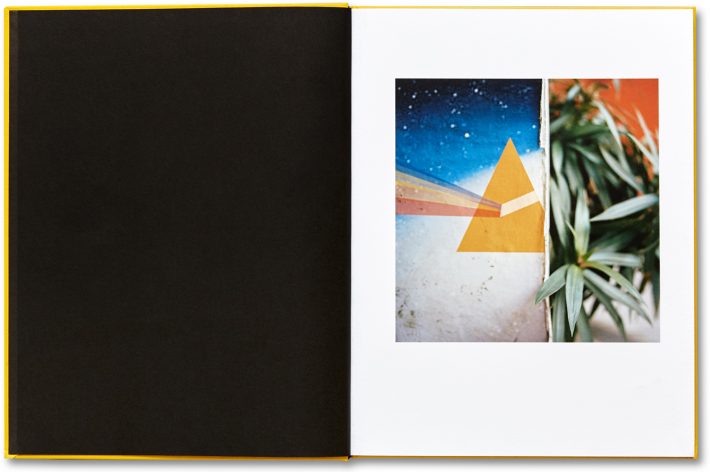

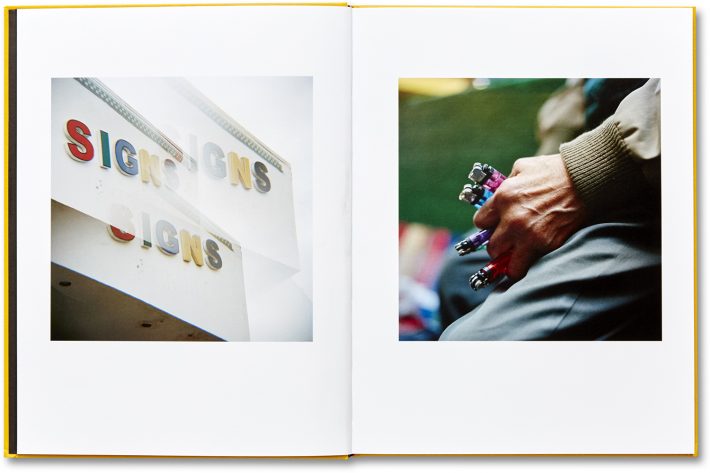

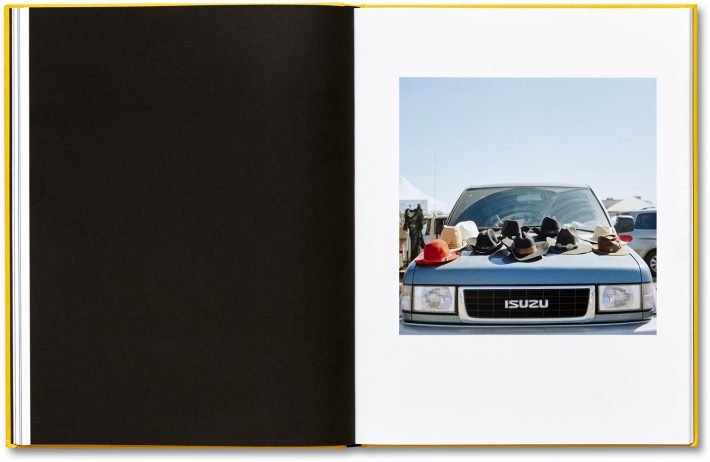

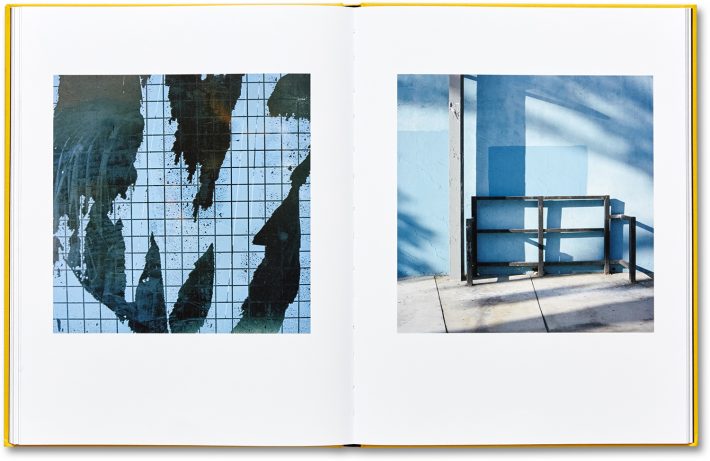

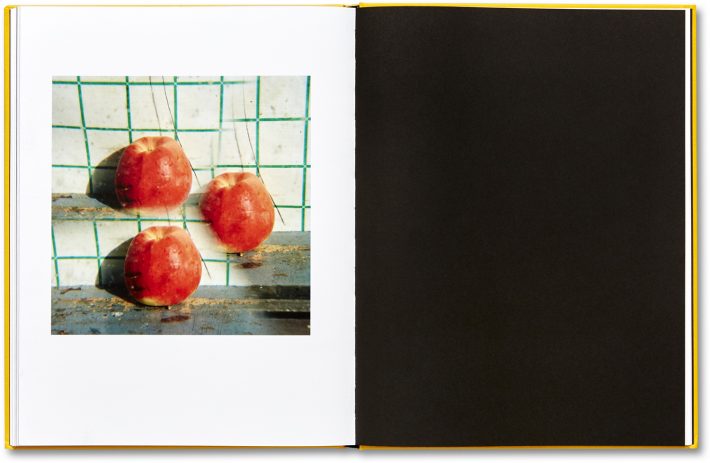

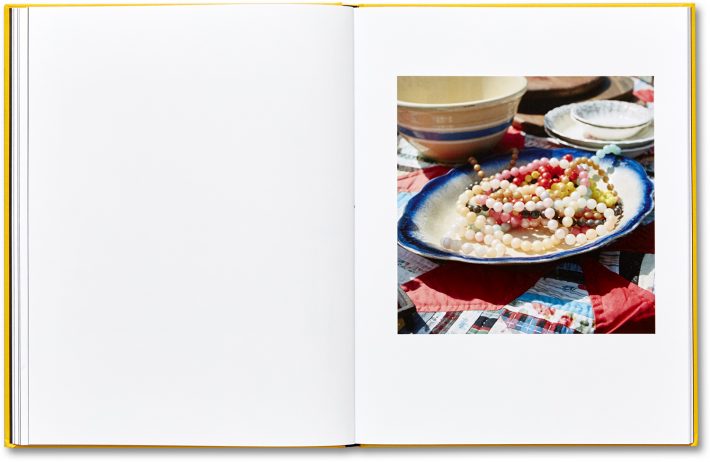

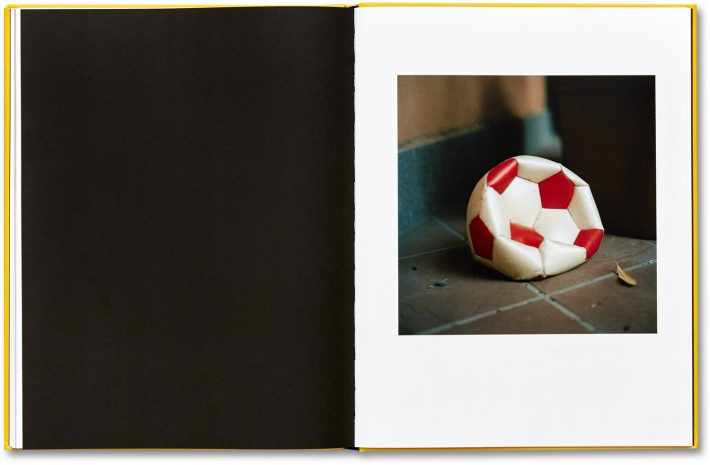

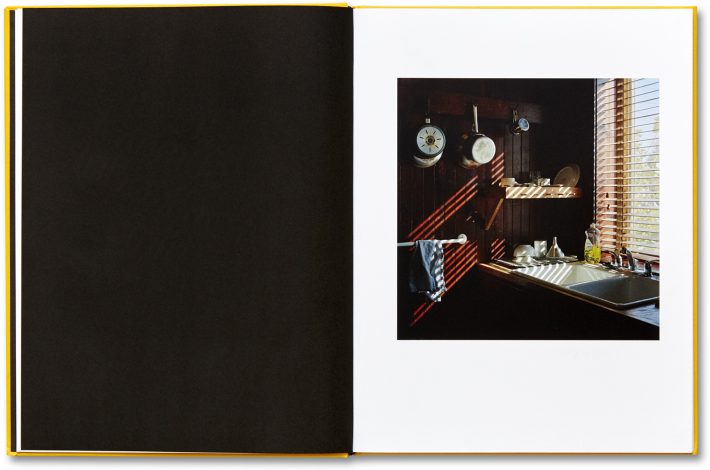

Jason Fulford, image from Picture Summer on Kodak Film (© MACK, 2020). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

What allowed you to return to the idea?

I softened my approach a bit. Someone says it in the book: shoot first, ask questions later.” You can take the picture anyway and question yourself about what you’ve done afterward. You can take the photo and then discard it, not show it to anyone. That’s another question I asked: “Is there a picture you’ve never shown to anybody?”

The book contains a long list of words in alphabetic order. Did you extract them from the texts you received or did each photographer make his or her own list?

Both. And one of the things I like most about this book is linked to this choice: by putting the words in alphabetic order, chance associations are formed that are sometimes very interesting and amusing.

What are the “prohibited” subjects that struck you most?

From each person I got what I wanted. It’s a book I’d never have been able to write by myself and I’m very happy with the result. Someone has written of not wanting to photograph cats, others metaphors, still others have spoken of certain commercial operations; some said celebrities, self-portraits, hands, stereotypes; there’s the street photographer who never asks permission to take people’s pictures and the one who, instead, never does so without asking.

In the book there are two inserts of pictures. Each has a caption and a page number. How were they chosen?

They are the images that photographers sent me as examples of when they’d broken a rule they’d set themselves. Then I added a phrase taken from their texts: a phrase that does not refer directly to the photograph and that creates an interesting connection. The name of the author is not given, just the number of the page on which his or her contribution can be found. It’s an idea taken from Nadja, a novel by André Breton in which various photos are inserted, each associated with a page number: if you go to the page you find, in the story, a reference to the photograph. It’s another way of browsing the book.

Do you think that this book tells us what each of the photographers believes?

It depends on the contributions. Some are lighthearted and others more serious. Roger Ballen’s, for instance, ends like this: “It is clear to me that at this time in history, a great percentage of contemporary artists and photographers are not interested in making the transition from exploring media-driven slogans to coming to terms with the enigmatic, mysterious boundaries of our short lives on this planet.”

And you, do you have a list?

I have a very long one. I got my sister to read it and she told me that it seems to describe my work exactly (laughs).

What effect did it have on you to hear that?

It touched something profound. Perhaps it made me feel guilty about the things I’m attracted to. I don’t know. Probably what I try to avoid rationally is also what, unconsciously, fascinates me.

Jason Fulford, image from Picture Summer on Kodak Film (© MACK, 2020). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

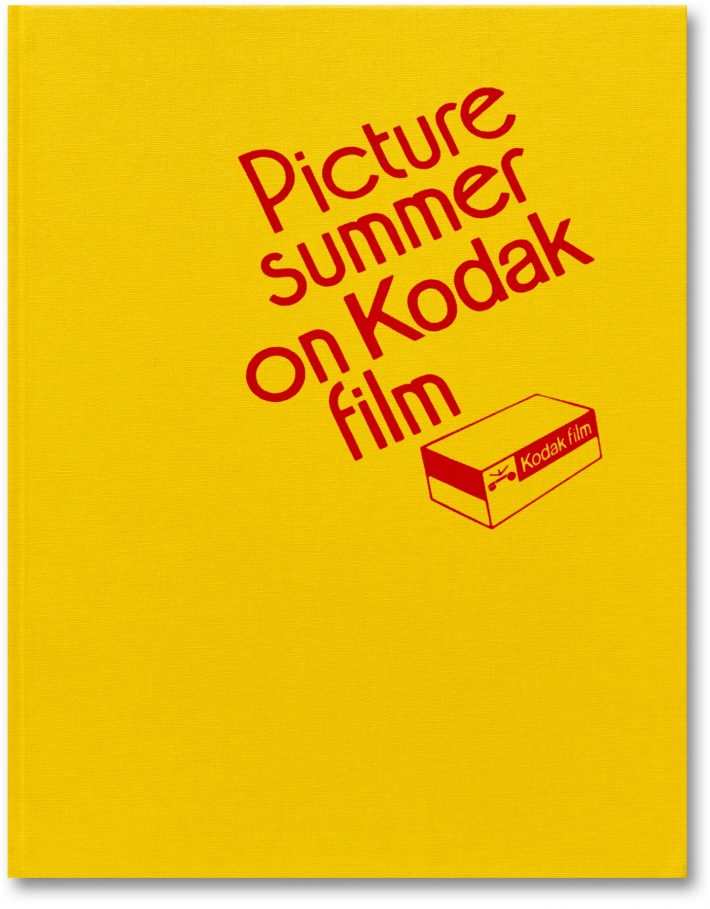

Your latest book of photographs was published in 2020 by Mack. It’s called Picture Summer on Kodak Film. How did it come about?

It started with a couple of trips to California. I was walking in some areas outside Los Angeles, and it was a very hot summer. I had a few photos that were going in a certain direction. Then I paid a visit to Italy, where, in Ferrara, I saw an exhibition on Giorgio de Chirico. I think it must have been in 2015. There was a group of still lifes from the 1916-17 period. I fell in love with them, even though I find it hard to explain why. It’s more than the simple and rather surreal aspect of seeing familiar objects juxtaposed in an unusual way. It’s an aesthetic, chromatic, spatial question; and there was a connection between those paintings and my pictures of California: a certain light, the idea of time coming to a stop, the colors, the shadows.

In the book, though, there are pictures taken in many countries.

Yes, one time I met my publisher, Michael Mack, and I showed him a series of projects I was working on. He was interested in this one and suggested not limiting it to California, so I widened the field. I inserted photos taken in Italy, Canada, Japan, Mexico, Nepal, Thailand and Vietnam.

And why that title?

Once, in California, I and my wife Tamara were struck by a beam of light that came from the window of an old store selling photographic and video material—it was the light reflected by some DVDs. The thing intrigued us and we went in. I bought a prism filter that I then used to take a lot of pictures, some of which ended up in the book. There were also some old Kodak adverts and one that stood out was a large cardboard cutout with a woman in a tennis outfit inviting you to photograph the summer. This idea of “photographing the summer” started to get mixed up with other ideas. I started thinking about de Chirico and photography, whose principal elements are light and time; photography is literally the time that you give the light to strike the film, but in de Chirico there is this very special light that creates a sense of absence of time. I tried to follow these two lines: time and the absence of time.

Et quid amabo nisi quod aenigma est? And what shall I love if not the enigma? This is the sentence that de Chirico wrote at the bottom of his first self-portrait in 1911 and that you have put on the back of the book cover. What kind of enigma interests you?

I love enigma because it’s something that lasts longer, that persists; it’s that quality in an image which attracts you, but you’re not really able to explain why. The enigma is what prompts you to go back and look at it again. This is the sort of image that I like to make for myself and that I hope will interest the reader too. I don’t want to do a book that you skim through, understand, appreciate and then that’s it. I want to create a work capable of stimulating interest every time someone looks at it, even at a distance of years.

Why?

I don’t know why. And in my life, things are the exact opposite; my wife and I like to solve crosswords, which once they are finished end up in the trash can, and you never think of them again. Food too is a pleasure that doesn’t last. I love moments that are not recorded, something that happens and doesn’t come back; perhaps it has to do with the experience I’ve had with certain images and that I wish was repeated.

Jason Fulford, image from Picture Summer on Kodak Film (© MACK, 2020). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

Do you love enigma only in images or in reality too?

Only in images, I think. Indeed, in real life I always try to understand everything.

But your images are pictures of real things.

In one sense yes.

And in the other sense?

The problem is the relationship between things. Like in de Chirico’s still lifes: that thing next to the other. It can happen in some photographs, and if it doesn’t happen in a single photo, that kind of experience can come from placing two images next to each other, which gives rise to something new. That’s the point for me.

With literature it can happen that what we read, a novel, a poem, helps us to live and to understand real life.

That’s what happens to me too.

And with photographs?

Not with my photographs.

Are there photographs by other people that help you understand the world and yourself?

Mostly it happens to me through words.

Whose words, for example?

There are some authors from the South that I love: Flannery O’Connor, Harry Crews, Tennessee Williams. And there is a French author I like to reread: Alain Robbe-Grillet. Recently I read Søren Kierkegaard’s Either/Or again too.

In the book you chose to include a photo of one of Josef Albers “homages to the square.” What relationship do you have with his work?

What impresses me about Albers is that, as a teacher, he put a great deal of emphasis on saying that art education should be an integral part of the liberal arts. Art, according to Albers, should not just be the basis for the training of artists, but also doctors, anthropologists, lawyers and so on. Art shapes thought. For me, the most important message he left is that perception often no longer corresponds to the facts. And he shows us it: two different colors appear the same to us if they are placed alongside other colors. I think this is his great lesson. And I like the way he delivered it to us: something very profound communicated in an essential and direct way. I love the forms of his “homages to the square,” as simple as child’s play but profound and multilayered from the conceptual viewpoint. This combination of simplicity and profundity is one of the characteristics of the art I love.

Jason Fulford, image from Picture Summer on Kodak Film (© MACK, 2020). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

The book that made you famous was The Mushroom Collector. In an interview published in Aperture you quoted something John Cage said: “It’s useless to pretend to know mushrooms. They escape your erudition. The more you know them, the less sure you feel about identifying them.” What relationship is there between photography and looking for mushrooms?

There are two ways of thinking about this relationship. The first is direct, literal. I always carry my camera with me because I don’t know what’s round the corner: I look for images that I don’t expect and when I see them, I shoot. The second way is metaphorical: the mushroom is a great metaphor for many different things. It grows underground, in the subconscious, sprouts here or there without being sown. It’s a clear and open metaphor. In Kinski, My Best Friend, the documentary about the difficult relationship between the director Werner Herzog and the actor Klaus Kinski, at a certain point Herzog talks about Fitzcarraldo and how the idea for the film arose: the legend of a man who to achieve his own goals had dismantled a ship in order to rebuild it on the other side of a hill. And Herzog adds: “It’s a great metaphor. For what? I don’t know to this day. But I know it’s a great metaphor.” The mushroom for me is a metaphor of the same kind. It’s a subject that can be compared to different things and at different moments in life.

You’re known for your talent in editing, the capacity to choose images and create significant sequences. How did you develop an interest in this part of the work?

I always say that photographers can be divided into two categories: the sculptors and the collectors. The former start with an idea and try to document it. I belong to the second kind: I bring home pictures I’ve taken in an intuitive way, for no particular reason, apart from the choice of the subject, and then I select them. It was fairly early in my career that I happened to discover the potentialities of editing and it has become fifty percent of my creative process. Taking photos is like gathering the words, the vocabulary, and editing is trying to put them in order, giving a meaning, even an ambiguous one, to those words.

What do you mean by ambiguous?

It’s something that has to do with what we what we were saying before about enigma: it’s what I’m trying to obtain with my sequences of photographs. Attaining that result is not easy. Often you find combinations of images that are dead ends, so you discard the combinations that don’t work and keep the ones that open up to more, new and unpredictable meanings. The definitive book becomes the one without dead ends.

Picture Summer on Kodak Film by Jason Fulford, cover, © MACK, 2020.

Jason Fulford, Picture Summer on Kodak Film (© MACK, 2020). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

Jason Fulford, Picture Summer on Kodak Film (© MACK, 2020). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

Jason Fulford, Picture Summer on Kodak Film (© MACK, 2020). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

Jason Fulford, Picture Summer on Kodak Film (© MACK, 2020). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

Jason Fulford, Picture Summer on Kodak Film (© MACK, 2020). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

Jason Fulford, Picture Summer on Kodak Film (© MACK, 2020). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

Jason Fulford, Picture Summer on Kodak Film (© MACK, 2020). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

Jason Fulford, Picture Summer on Kodak Film (© MACK, 2020). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

Jason Fulford, Picture Summer on Kodak Film (© MACK, 2020). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

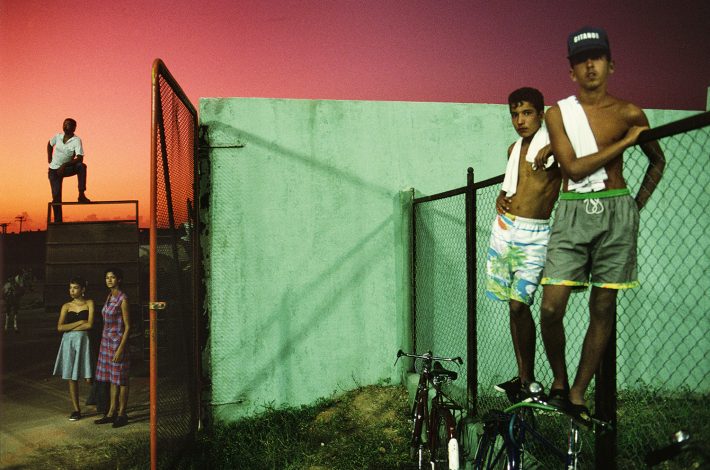

Alex Webb, Sancti Spiritus, Cuba, 1993; from Photo No-Nos: Meditations on What Not to Photograph, edited by Jason Fulford (© Aperture, 2021). © Alex Webb.

Jeff Mermelstein, New York City, 1993; from Photo No-Nos: Meditations on What Not to Photograph, edited by Jason Fulford (© Aperture, 2021). © Jeff Mermelstein.

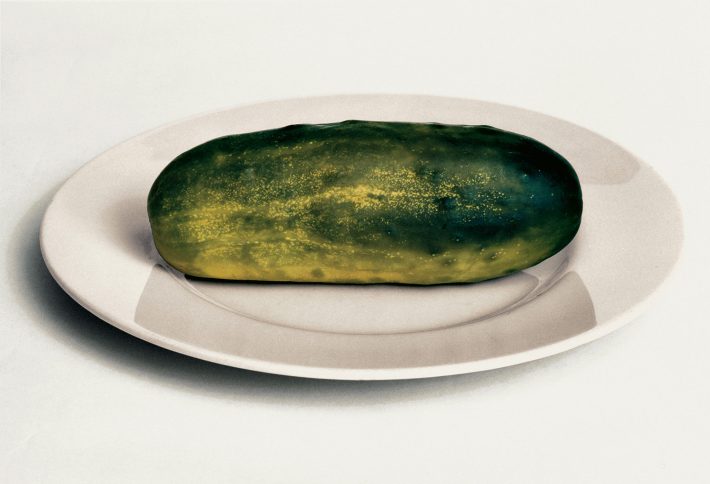

Duane Michals, A Gursky Gherkin Is Just a Very Large Pickle, 2001; from Photo No-Nos: Meditations on What Not to Photograph, edited by Jason Fulford (© Aperture, 2021). © Duane Michals.

September Dawn Bottoms, Solofa Halley of Jungle Boyz Exotics in Tulsa, Oklahoma, October 2019; from Photo No-Nos: Meditations on What Not to Photograph, edited by Jason Fulford (© Aperture, 2021). © September Dawn Bottoms.