29 December 2018

Art is always ahead of its time, and so it is that a century after his death Egon Schiele (1890-1918) turns out to be a perfect contemporary of ours. All it takes is a visit to the retrospective at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris, curated by Suzanne Pagé, Dieter Buchhart and Olivier Michelon (over a hundred paintings and drawings, many of them in private hands, on show until January 14, 2019), to realize the extraordinary prescience that Schiele displayed in terms of his representation of the distinctive characteristics of modernity: the solitude of the individual, anguished narcissism, a sexual drive torn between libido and death instinct, the isolation of artists that leads to their negation and to the negation of art. All themes that pervaded the culture of crisis in fin-de-siècle Vienna, the Vienna of Schoenberg, Wittgenstein and Adolf Loos, cosmopolitan theater of the Experiment Weltuntergang, a magnificent laboratory where, speaking twelve languages, people experimented with the end of the world and the advent of decadence under the aegis of the Imperial-Regia, an exhausted monarchy that had now passed its peak in which all artists, shut up in their cells, could shout out their madness to the world any way they wished.

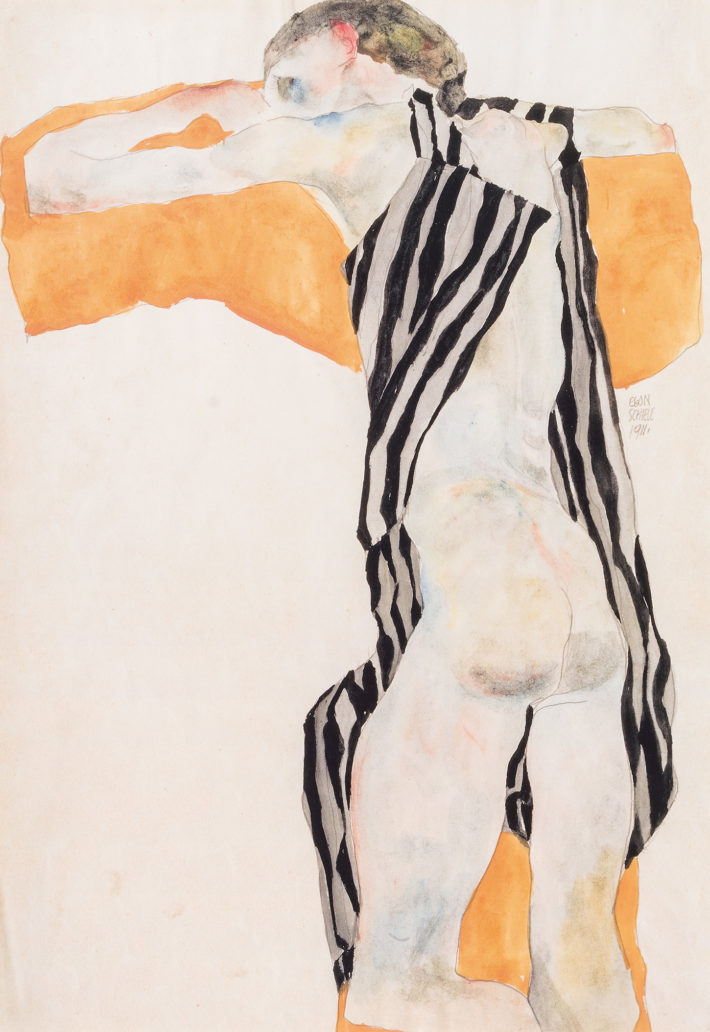

Egon Schiele, Sitzender männlicher Rückenakt (Seated Male Nude, Back View), 1910. Watercolor, gouache and black crayon on paper. Neue Galerie New York. Gift of the Serge and Vally Sabarsky Foundation, Inc. Photo: © Hulya Kolabas for Neue Galerie New York.

And yet nothing seemed predestined for that delicate and slender boy, son of a stationmaster in Tulln an der Donau, a town on the outskirts of Vienna, left without a father at the age of just fourteen following his death from syphilis in 1904 after a period of slow mental degeneration. It’s true that he started to draw very early on. He first picked up a pencil when just eighteen months old and never put it down again. He was a precocious, highly innovative genius and would burn his life out in a flash, dying of Spanish flu at the age of just 28 after having anticipated the crisis of the modern, the wounds of the Great War and many of the lacerations of the 20th century. He made rapid progress right from the start, exasperating his professor of drawing at the Academy of Fine Arts, Christian Griepenkerl, who reassured his mother when she asked if he had talent: “Yes, too much. He messes up the entire class.”1 He was a taciturn and ardent child, and while still very young showed a true calling, neglecting his homework so he could draw all the time. This drove his father so crazy that one day, tormented by the myriad sheets of paper scattered around the house, he flew into a rage and made a bonfire out of them. Schiele was traumatized for life by this, and relived the trauma as an adult when, convicted of indecent behavior in 1912, he spent three weeks in jail and had to witness another burning of his drawings, ordered by an inflexible judge.

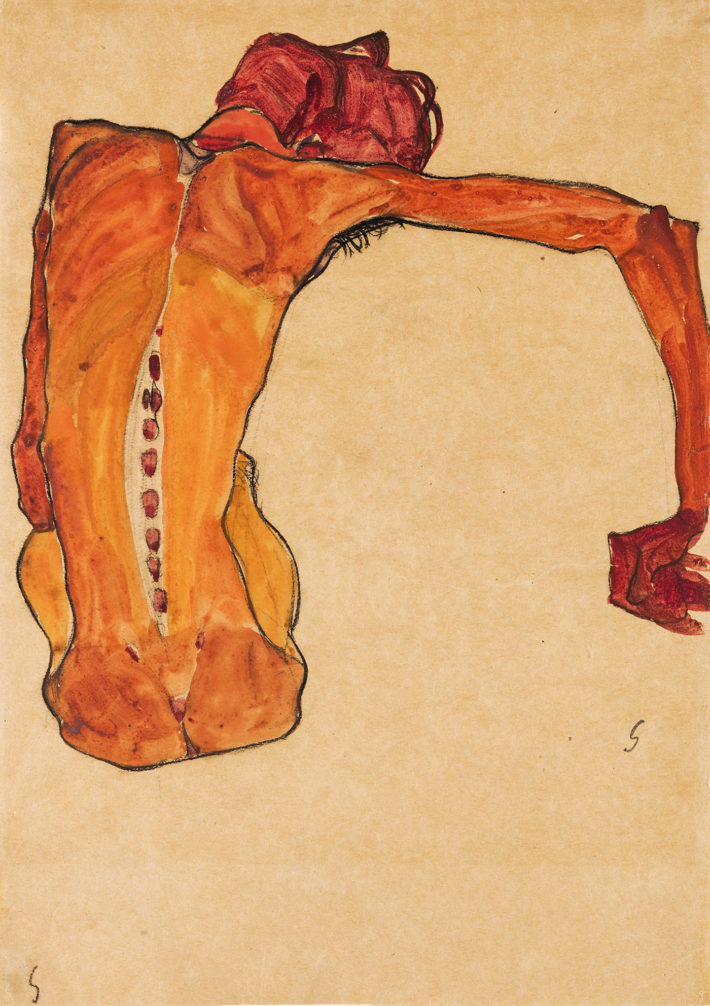

At the outset, to give free rein to his torments and anxieties, Schiele chose the medium of drawing and a line able to “anchor the content to the form,” as Werner Hofmann put it.2 From the ornamental line of the Secession, close to the Jugendstil, he moved on to the Expressionist one of the 1910s, in reaction to the mythological compositions and worldly themes of Gustav Klimt. He used it to churn out portraits and self-portraits of a distorted and unbalanced character, where the outlines and a few touches of paint set the figures in tension with the empty background. He tried out new techniques like painting wet-on-wet, letting the water produce the forms, as can be seen in some stunning watercolors on show in Paris (Seated Male Nude, Back View, 1910, or Moa, 1911). And set off in search of an equilibrium, pursuing a more disturbing fluidity, one that was attentive to the psyche of his subjects and influenced by puppet theater and the world of mime. Thus, over the course of ten years, Schiele managed to come up with a range of extraordinary solutions, of which the exhibition in Paris offers a perfect synthesis. He was devoted to “knowledge through the flesh” and “deformation of the body as such, in the absence of space,” in the words of Werner Hofmann,3 as if it were “a landscape with ruins,” adds Dieter Buchhart.4 He used line like a chisel to carve himself and to spread his discoveries around, explains Alessandra Comini,5 cultivating an extreme exhibitionism, with no sham circumspection, in order to offer powerful, upsetting and immodest images of himself and others.

Egon Schiele, Moa, 1911. Gouache, watercolor and pencil on paper. Private collection, London. Photo: © Mathias Kessler, 2017.

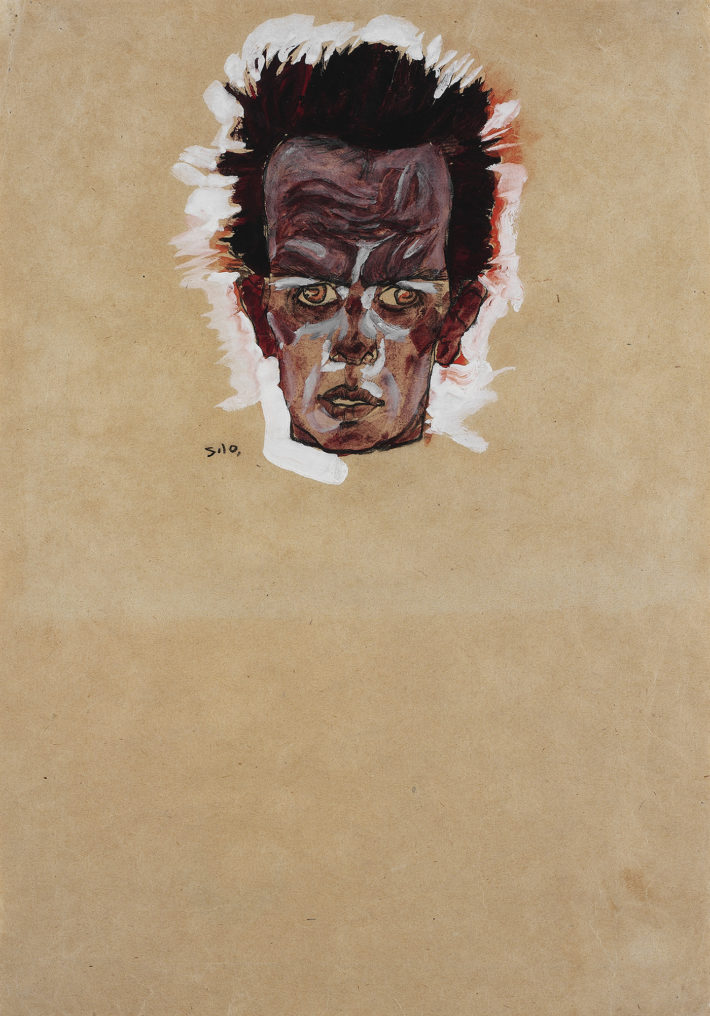

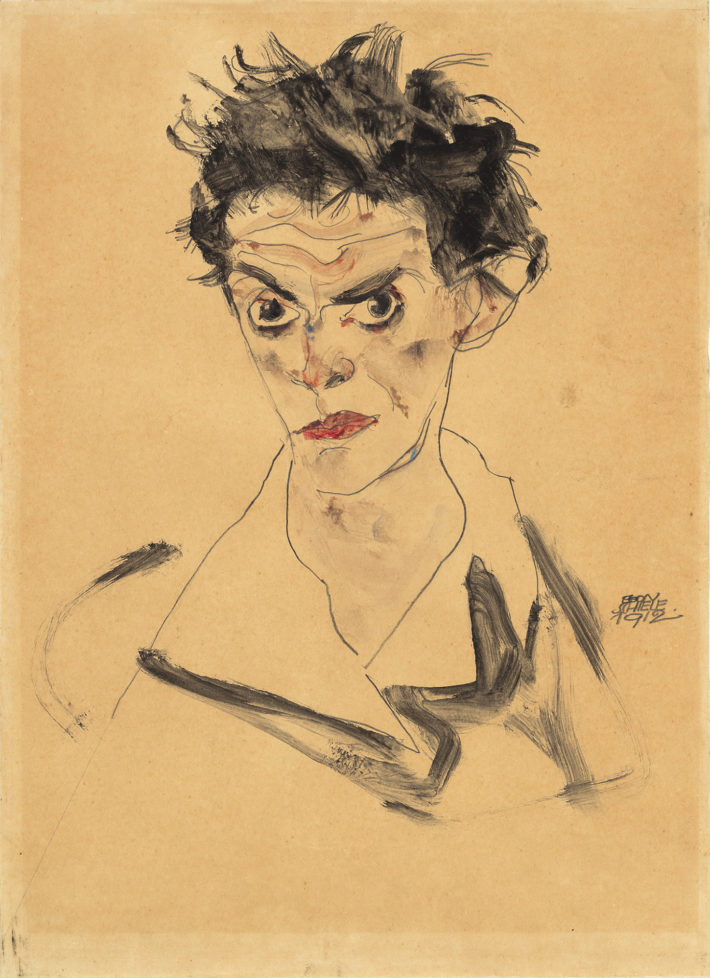

After leaving the academy, Schiele entered straight into the world of art, bursting into the garden villa in Josefstadt that housed the studio of his teacher Gustav Klimt, who seems to have been fascinated by that pupil with an emaciated and rebellious air. At the age of 19, aware of himself and his talent, Schiele needed few means to create: all it took was an old pier glass inherited from his mother, drawing paper, pencils and grease pastels in order to start drawing in a new and provocative way, renouncing relief and three-dimensional shading and following the line in itself, indifferent to any sense of shame, modesty or pity, so as to put on display searing obsessions, forbidden feelings, the storm raised by the most pressing impulses. Thus we find him in front of the mirror, portraying himself as he masturbates, with an outsized phallus in his hands (Eros, 1911). The end of ideal beauty, of the “microgenitomorphism” of the ancients theorized by Polykleitos: the penis is painted as he saw it, in its crude reality, exalted and represented according to nature. This was in 1910, a time when masturbation was considered an illness, a cause of madness, and when even Freud, who considered it a “primary addiction,” was loath to mention it to his adolescent son, whom he had treated by a colleague. Schiele, whom Freud never met and with whose works he was not familiar, would be the artist who best illustrated the reshaping of consciences and forms underway in Viennese culture: a reformation that was at the same time “affirmation of self and destruction, postulate of a modernity and critique of modernity itself,” as Jean Clair points out in his fine essay.6 Was not modern man master of his own house, was he not in control of himself? Was he at the mercy of a mysterious energy, Eros, the libido, the death instinct that drove him into compulsive repetition in order to find pleasure and pain? Thus we find Schiele depicting the drama of the modern ego in his double self-portrait in pencil on paper, where a self of tranquil appearance is presented in the company of another self, who instead has wild eyes, a furrowed brow, a mop of hair on his head and outstretched hands with long splayed fingers, while the other holds him still from behind and peers down his nose at him (Double Self-Portrait, 1910). In another self-portrait, Schiele paints himself with a formless mass of hair, looking as if it were standing on end after an electric shock, and a high, wrinkled forehead, curly eyebrows, a faraway look, his gaze turned inward on an unfathomable black hole, and slightly parted lips (Self-Portrait, Head, 1910).

Egon Schiele, Eros, 1911. Gouache, watercolor and chalk on paper. Private collection. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

The same year, Schiele returned to the double self-portrait with the Selbstseher, or viewer of himself, in which he showed the dark demon pushing him from behind to carry out obscene acts, the only one responsible for his perversions (Self-Seer, 1910). In this way he was able to articulate his poorly suppressed anger, the anxiety and disquiet that drove him to introspection. It was as if in portraying himself he wished to rediscover his childhood traumas, the impulses of his soul: “Have adults forgotten how corrupt, sexually driven and aroused they were as children? Have they forgotten how the frightful passion burned and tortured them when they were children? I have not forgotten, for I have suffered terribly under it,” wrote Schiele.7 And in this research he also involved his sister Gerti, four years younger than him, who posed for him in the nude and took part in long clandestine sessions of anatomy, along with other kids he picked up on the street, as well as models professionally disposed to adopt more provocative poses. Little by little, the ornamental line, the line of Klimt, master of Jugendstil fluidity, began to break up into a tense, angular, expressionistic line. In 1912 Schiele left for Krumau, the medieval town in Bohemia less than two hundred kilometers from Prague, where his mother was born and where he lived with the model Wally Neuzil. Shortly afterward, the pair moved to Neulengbach, fifty kilometers from Vienna, into a little place with a garden where Wally played mistress of the house and Schiele painted their portraits and The Hermits (1912), a large picture with two figures in which he portrayed himself next to Klimt. Fortune smiled on Schiele and he showed in Vienna, Munich, Cologne and Budapest, but then turned its back on him the day he was accused of indecency: arrested, he suffered the indignity of the seizure of a hundred or so erotic drawings and then, after three weeks of imprisonment and a hasty trial, was released. In prison Schiele kept a diary, in which he reflected on art: “Kunst kann nicht modern sein. Kunst ist urewig” (“Art cannot be modern. Art is primordially eternal”).8 He tried to paint on the walls with his saliva, before obtaining paints and brushes with which he executed thirteen watercolors, including a view of his cramped cell and pictures of his chair and his clothes, infusing his life into the inanimate objects, and four fabulous self-portraits in which he painted himself in a vertical position, as if hanging in empty space. “Hindering the artist is a crime, it is murdering life in the bud,” he wrote in block capitals next to the first. Lying on his back on the pallet, wrapped in his red coat with its enormous buttons, without showing his feet or his hands, the prisoner directs an imploring gaze from the depths of his wide eyes, in order to convey his feelings of outrage, indignation and humiliation (I Love Antitheses, 1912). In another portrait his hands reappear, contracted as if trying to seize hold of empty space, clutching at the coat and crumpling the cloth (I Will Gladly Endure for Art and My Loved Ones, 1912). They are a symbol of his return to life.

Egon Schiele, Selbstbildnis, Kopf (Self-Portrait, Head), 1910. Gouache, watercolor and charcoal on paper. Ömer Koç. Photo: © Hadiye Cangókçe.

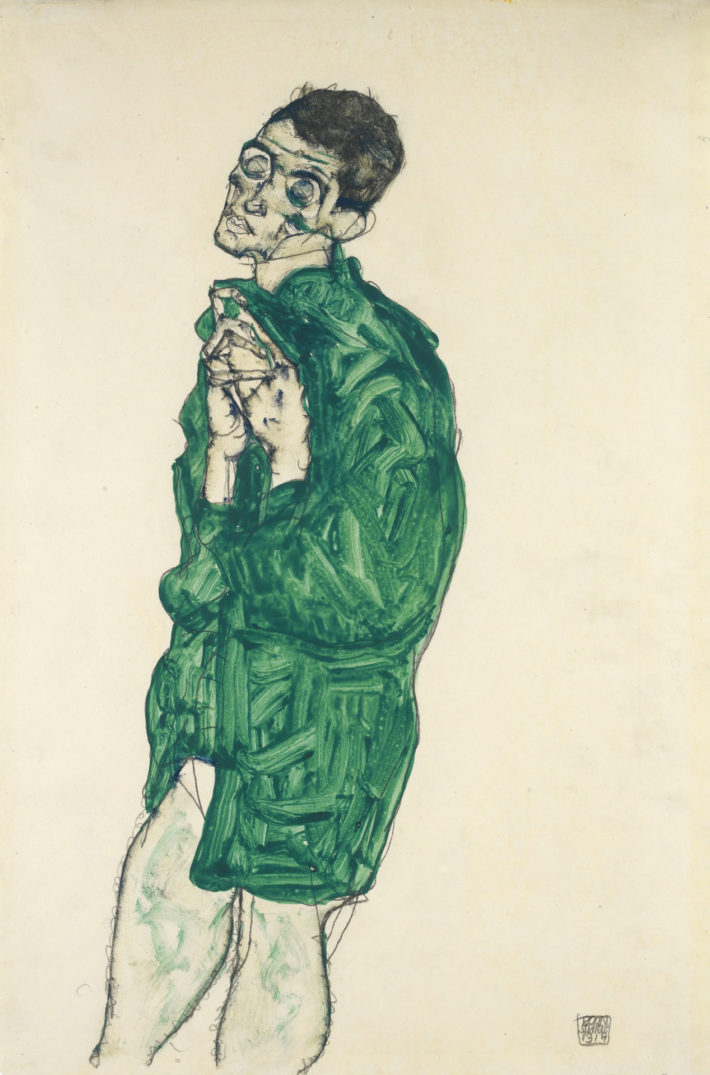

The artist was free again and embarked on a series of ascetic drawings of himself alone, or next to Wally, his muse, whom he clasps in a consoling embrace. But in the meantime, another self begins to stir and agonize, its eyebrows knitted, its hair disheveled, its cheeks ruddy, its hands held out in a defensive gesture, while its body gives off a strange reddish glow. At the end of 1913 he invented a new logo, enclosing in a rectangle his signature written in block letters on two rows: it was as if after the long exploration of the emptiness at the heart of his existence he had decided to retreat into himself, observes Alessandra Comini, and attempt to establish a less conflictual relationship with the world. And so at the exhibition held in Vienna in December 1914, Schiele chose to portray himself as a modern martyr, persecuted and tortured like San Sebastiano (Self-Portrait in Green Shirt with Eyes Closed, 1914). His expressionistic line reached the peak of abstraction, of its angular and broken character. Schiele took the rules of anatomy to a grotesque extreme, treating the faces of his models as if they were the heads of manikins, but the geometry was always based on their organic structure. When he tried to emerge from his feelings of despair and resentment, Klimt came to his aid, persuading the Hungarian industrialist August Lederer to entrust Schiele with the portraits of his children. What counted now was not just the precision of the contours, the definition of the line. What mattered above all was the reflection of inner life. His pictures were selling well. In 1913 he moved house, going to live in an attic at 101 Hietzinger Hasuptstrasse, where he had a studio on the ground floor. Opposite lived the Harms sisters, Adéle and Edith, 23 and 21 years old respectively, daughters of a German who worked for the Austrian railroads. On the eve of the First World War Schiele began to court Edith. In February 1915 he was mobilized, but was given a deferment for health reasons. Drafted again in May, he left for Prague on June 21, 1915, four days after marrying Edith. Although he did not want to give up Wally, she was so outraged by the marriage that she left him, going to work as a volunteer nurse in a military hospital. Three years later, on October 28, 1918, shortly before the armistice, Edith died of the Spanish flu and Schiele, already ailing himself, portrayed the couple lying on the bed in a tender embrace (Lovers, 1918, unfinished). Three days later, on October 31, 1918, he too succumbed to the influenza.

Egon Schiele

Curated by Suzanne Pagé, Dieter Buchhart and Olivier Michelon

Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris

October 3, 2018-January 14, 2019

Egon Schiele, Liebespaar (Lovers), 1918 (unfinished). Oil on canvas. Private collection, Leopold. Photo: © private collection, Leopold.

Egon Schiele, Liegende Frau mit blondem Haar (Reclining Woman with Blonde Hair), 1914. Transparent and opaque watercolor over graphite on paper. Baltimore Museum of Art, Fanny B. Thalheimer Memorial Fund and Friends of Art Fund. Photo: © Mitro Hood.

Egon Schiele, Selbstbildnis mit Lampionfrüchten (Self-Portrait with Chinese Lantern Plant), 1912. Oil and gouache on wood. Leopold Museum, Vienna. Photo: © Leopold Museum, Vienna.

Egon Schiele, Die Eremiten (The Hermits), 1912. Oil on canvas. Leopold Museum, Vienna. Photo: © Leopold Museum, Vienna.

Egon Schiele, Selbstdarstellung in grünem Hemd mit geschlossenen Augen (Self-Portrait in Green Shirt with Eyes Closed), 1914. Gouache and pencil on paper. Private collection. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Egon Schiele, Liegender Mädchenakt in gestreiftem Kittel (Reclining Nude Girl in Striped Smock), 1911. Pencil and watercolor on paper. Private collection, Vienna. Courtesy of Kunsthandel Giese & Schweiger, Vienna. Photo: © Kunsthandel Giese & Schweiger, Vienna.

Egon Schiele, Selbstbildis (Self-Portrait), 1912. Watercolor over graphite on light brown wove japan paper. National Gallery of Art, Washington. Gift of Hildegard Bachert in memory of Otto Kallir, 1997. Photo: Courtesy of National Gallery of Art, Washington.

Egon Schiele, Selbstporträt mit Pfauenweste, stehend (Self-Portrait with Peacock Waistcoat, Standing), 1911. Gouache, watercolor and black crayon on paper, mounted on cardboard. Ernst Ploil, Vienna. Photo: Courtesy of Ernst Ploil, Vienna.

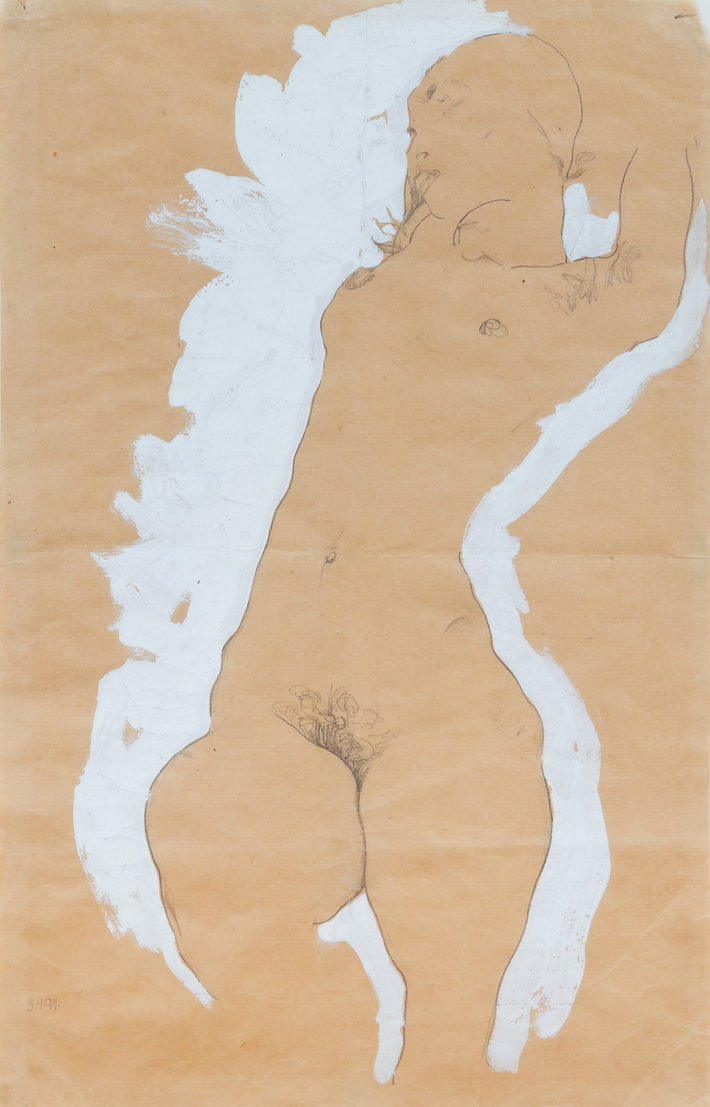

Egon Schiele, Mädchenakt mit weisser Umrandung (Female Nude with White Border), 1911. Gouache and pencil on paper. Collection of Johan H. Andresen. Photo: © Christian Øen.

Egon Schiele, Woman with Mirror, 1915. Gouache and pencil on paper. Tel Aviv Museum of Art Collection, c. 1953. Photo: © Elad Sarig.

Egon Schiele, Seated Semi-Nude with Hat and Purple Stockings (Gerti), 1910. Charcoal and watercolor on paper. Private collection. Courtesy of W&K – Wienerroither & Kohlbacher, Vienna. Photo: Courtesy of W&K – Wienerroither & Kohlbacher.

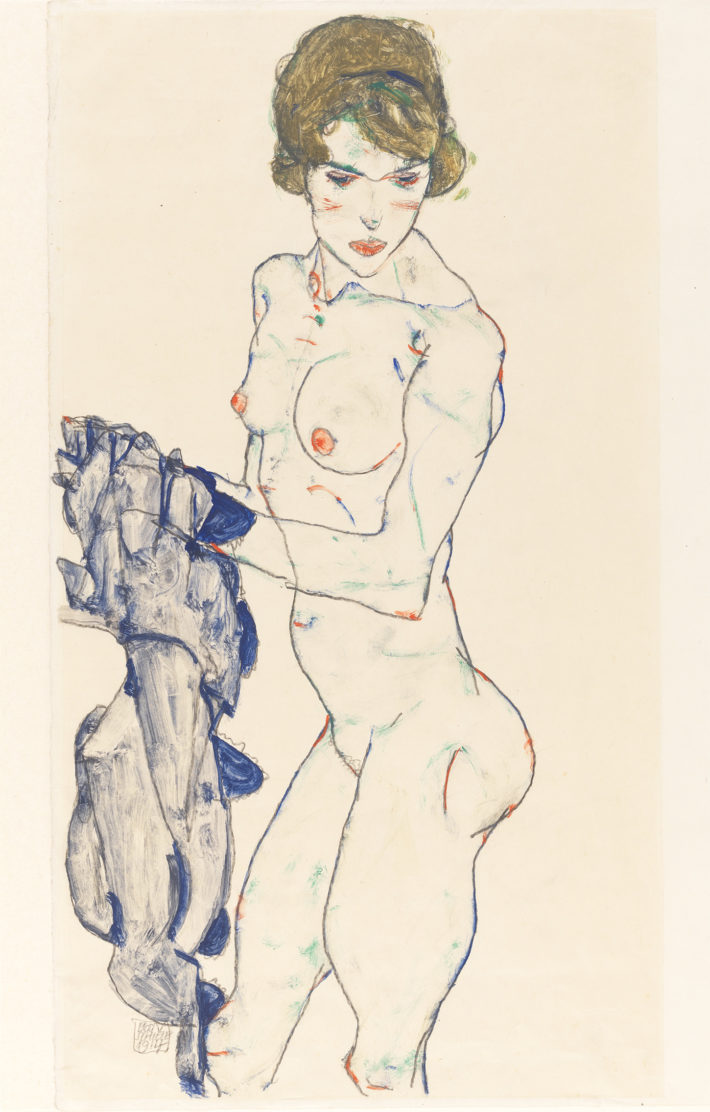

Egon Schiele, Stehender Akt mit Tuch (Standing Nude with a Patterned Robe), 1917. Gouache and black crayon on buff paper. National Gallery of Art, Washington. Gift of The Robert and Mary M. Looker Family Collection, 2016. Photo: Courtesy of National Gallery of Art, Washington.

Egon Schiele, Weiblicher Akt mit blauem Tuch (Standing Female Nude with Blue Cloth), 1914. Gouache, watercolor and graphite on vellum paper. Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg. Photo: © Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg.

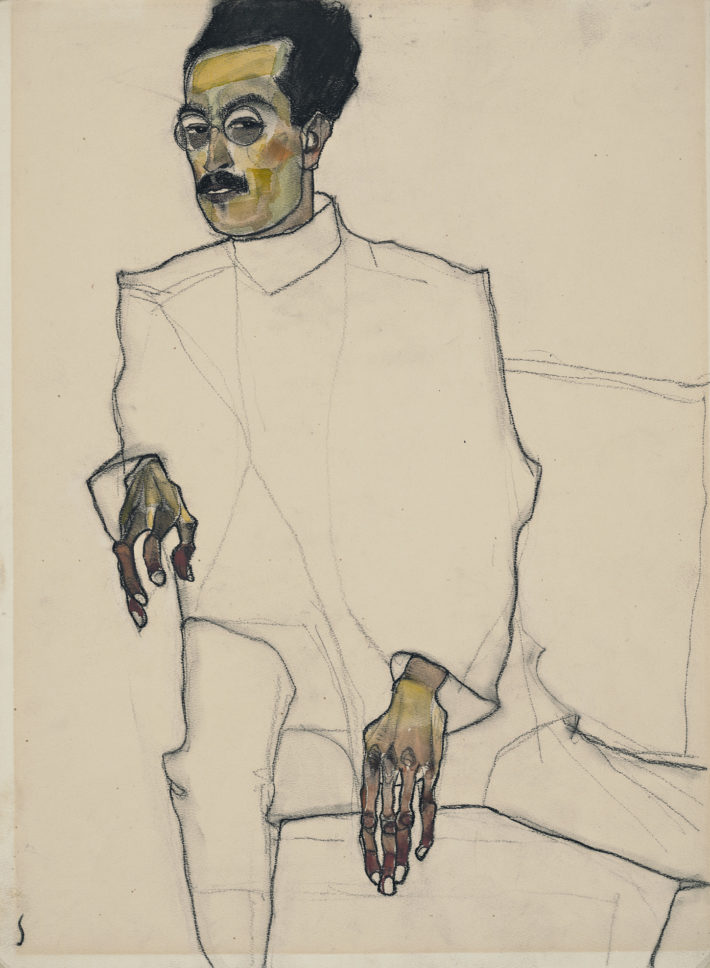

Egon Schiele, Portrait of Doctor X, 1910. Black crayon and watercolor on paper. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut, The Ella Gallup Sumner and Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund. Photo: © Allen Phillips / Wadsworth Athemuseum.

Egon Schiele, Ich werde für die Kunst und meine Geliebten gerne ausharren (I Will Gladly Endure for Art and My Loved Ones), 1912. Brush, watercolor and pencil on Japan paper. Albertina, Vienna. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Notes

1 Anton Peschka Jr, Die Wahrheit über Egon Schiele, unpublished manuscript, 45; text cited by Jane Kallir in “Egon Schiele en quête de la ligne parfait,” in Egon Schiele, catalogue of the exhibition at the Fondation Louis Vuitton (Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 2018), 28.

2 Werner Hofmann, “Egon Schiele”, Experiment Weltuntergang. Wien um 1900, catalogue of the exhibition at the Hamburger Kunsthalle (Munich: Prestel, 1981), 150-51; cited by Dieter Buchhart in “Schiele et la ligne existentielle,” in Egon Schiele, 14.

3 Werner Hofmann, “Das Fleisch erkennen”, in Alfred Pfabigan, ed., Ornament und Askese. Im Zeitgeist des Wien der Jahrhundertwende (Vienna: Christian Brandstätter, 1985), 123; cited by Buchhart in “Schiele et la ligne existentielle”, ibidem, 25.

4 Buchhart, “Schiele et la ligne existentielle,” 25 and 26.

5 Alessandra Comini, “Dessin: la ligne de vie d’Egon Schiele”, in Egon Schiele, 42.

6 Jean Clair, “Modernité d’Egon Schiele”, in Egon Schiele, 37.

7 Egon Schiele in Arthur Roessler, ed., Egon Schiele im Gefängnis (Vienna: Konegen, 1922), 33; cited by Comini in “Dessin: la ligne de vie d’Egon Schiele,” 42.

8 Egon Schiele, cited by Jean Clair in “Modernité d’Egon Schiele,” 36.