27 January 2020

Charlotte Perriand’s life (1903-99) spanned a century, but she was only 25 when she designed several pieces of furniture that are today regarded as classics. Who was this young woman who was going to leave such a mark, designing from a very early age the furnishings for masterpieces of Le Corbusier’s architecture like Villa Church, Villa Savoye and the Cité de Refuge de l’Armée du Salut, not to mention the Swiss Pavilion at the Cité Universitaire? A pioneer of interior design, an open-minded and independent artist convinced that “there are no readymade formulas” in creation. Throughout her life she delighted in mixing things up, passing naturally from design to architecture and city planning, flirting freely with painting, sculpture and photography in order to bring about a synthèse des arts, and always turning back to nature to draw new resources and new ideas in view of the sole imperative of her life: putting the art d’habiter on a new foundation, improving the everyday existence of her contemporaries. We can read the story of this extraordinary woman who revolutionized the modern culture of living and the very way in which we look at art and experience it in the autobiography she wrote at the age of 90, relating in detail and without any shame her coming of age, the disappointments, difficulties and many successes that punctuated her life.1 But today we can also gain a direct insight into it through her interior designs, and through the drawings, plans, furniture, spaces and constructions that she realized over the course of her career.

Charlotte Perriand, Fauteuil pivotant, B302, 1927. Photo: © Paris, 2019, Courtesy of Vitra Design Museum.

In fact, the Fondation Louis Vuitton is devoting a fascinating exhibition to her. Entitled Charlotte Perriand: Inventing a New World, it is open until February 24 and accompanied by a fine catalogue edited by Sébastien Cherruet and Jacques Barsac, to which Charlotte’s daughter, Pernette Perriand-Barsac, has also contributed.2 As soon as you go into the “sailing ship” designed by Frank Gehry in the Bois de Boulogne, entering the first of the nine galleries that host the exhibition, you encounter the original Chaise longue basculante B 306, the famous chrome-plated tubular steel chair with a seat made of rubber covered with fabric designed for the interiors of Villa Church and La Roche, in line with Le Corbusier’s program. Charlotte Perriand came up with the design for it in 1928, taking her inspiration from Dr. Pascaud’s medical recliner and Thonet’s rocking chair. “I beg you to emphasize that it functions simply by sliding, without any mechanical intervention,” she wrote in the patent,3 indicating the various possible positions. The chrome steel structure, welded like a bicycle frame, was supposed to permit the chair’s mass production at a reduced cost. But while that chair, which has now been brought out again by Cassina, partner of the exhibition and official manufacturer of Charlotte Perriand’s furniture, became an iconic piece and symbol of identity par excellence for the cultured and refined upper middle class, ninety years ago it was too advanced, too far ahead of its time, and proved to be a commercial flop: brought into production by Thonet in 1930, just 170 of them were sold in ten years. The other original piece on display in Paris, by way of introduction to Charlotte Perriand’s new world, is the Fauteuil pivotant of 1927, a swivel armchair upholstered in red leather with a round seat and a curved back, both of them padded, that stands on a very light framework of chrome-plated tubular steel. With this invention, the young CP, only child of a tailor and seamstress from Savoy with an atelier on Place du Marché Saint-Honoré and freshly graduated from the Ecole des Arts Décoratifs, dismissed the dominant Art Deco style of the time, perhaps without even realizing it, and before she entered Le Corbusier’s studio.

Charlotte Perriand, Collier roulement à billes chromées, 1927. Photo: © Adagp, Paris, 2019 / AChP.

She was a young woman with an infectious smile, sparkling blue eyes and blond hair, cut very short in the style of a street urchin, and went around in Charleston dresses with geometric patterns. She did nothing but draw and one day took her sketches to a talented artisan with a workshop in the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, from whom she learned the workings of the strangest mechanisms. It was he whom she got to make a necklace out of chromed copper ball bearings, the Collier roulement à billes inspired by one of Fernand Léger’s still lifes (Le Mouvement à billes, 1926) that would become the declaration of her freedom and of that of the women of her generation, as well as “a symbol of my adherence to the twentieth-century machine age,” as she would declare.4 Fascinated by the civilization of machines, by airplanes and automobiles, she drank her fill of the creative energy that in those years inspired the Cubism of Braque and Picasso, the airy sculptures of Calder and the great allegories of Léger (her future and unfailing friend, who referred to her as “my little seal”), like that monumental oil painting entitled Le Transport des forces, executed for the International Exposition of 1937, which looms over the Chaise longue and the Fauteuil pivotant in the exhibition in Paris: a picture in which the contrasts between colors and forms represent the modern factory and the industrial progress that was offering humanity the possibility of control over nature.

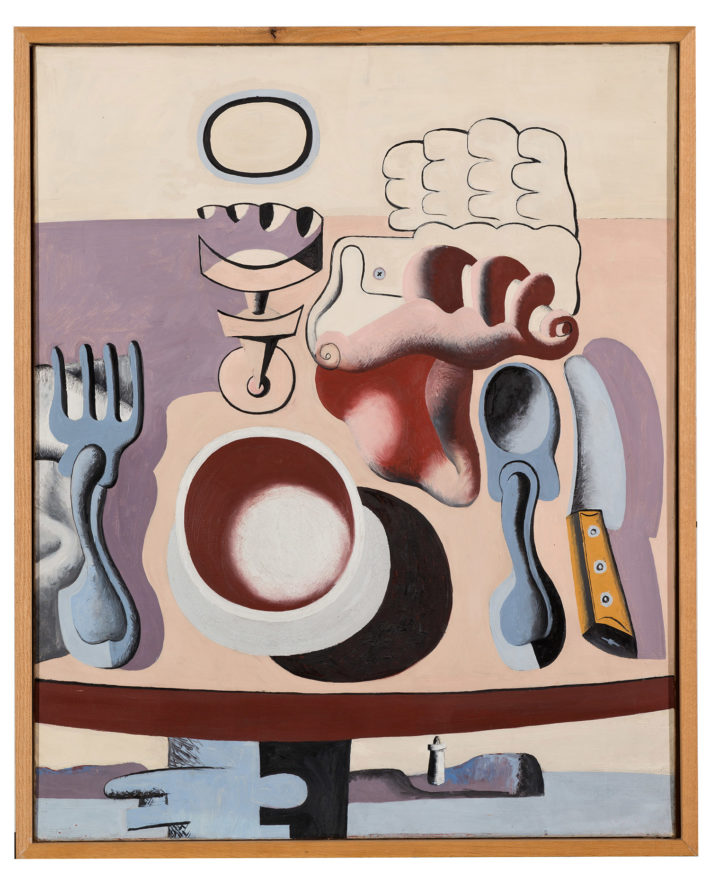

Fernand Léger, Nature morte (Le Mouvement à billes), 1926. Photo: © Adagp, Paris, 2019 / Kunstmuseum Basel, Martin P. Bühler.

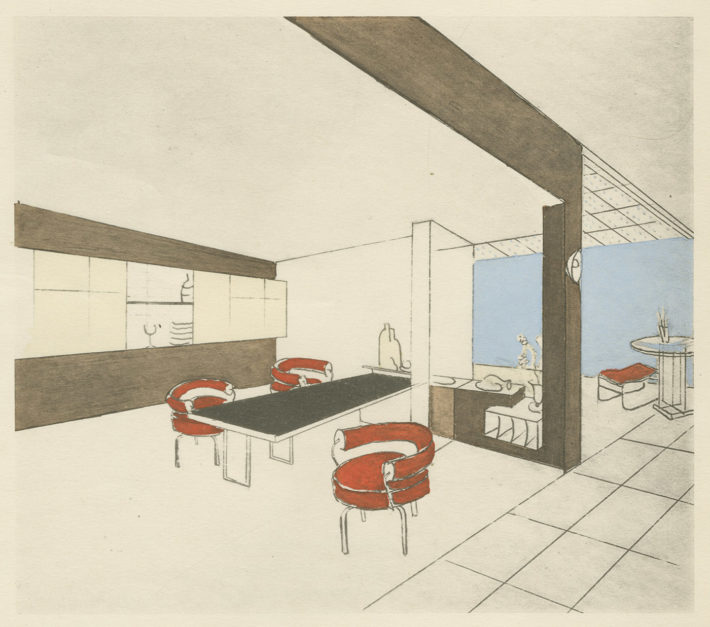

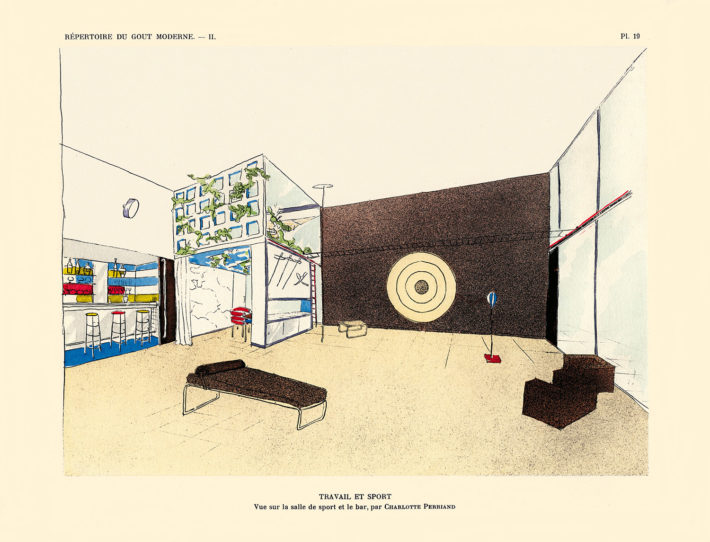

A champion of the modern, Charlotte Perriand was the first to apply to the furnishing of interiors the rational principles of Taylorism, which had transformed the traditional factory into a large-scale industrial concern scientifically organized in every aspect, including the arrangement of its offices. And yet, as a genuine pioneer, she designed the famous swivel armchair for her apartment on Place Saint-Sulpice, where she had gone to live with her husband, Percy Scholefield, a phlegmatic and considerably older English textile merchant and friend of her parents whom she married at a very young age in order to be able to leave home and seek her freedom. That first home, the former studio of a photographer with an immense expanse of glass facing onto the church, became for her an experimental laboratory of forms and life. Charlotte had thought of everything. It was there that she installed a folding door and the piece of furniture that was to become another legend of 20th-century interior design, the famous Bar sous le toit, or “bar in the attic,” that would be shown at the Salon d’Automne in 1927: a nickel-plated copper and anodized aluminum bar cabinet, equipped with utensils and crockery and made with industrial materials and techniques, that served as a sitting room for gatherings of her artist friends, Gérard Sandoz, Jean Fouquet, the painter Marianne Clouzot, Jacqueline Lamba and her new boyfriend André Breton, the photographer Dora Maar (who in 1935 would become Picasso’s companion), with whom she discovered the jazz of Louis Armstrong and the African dances of Josephine Baker. An adjoining space was used as the dining area, re-created in 1928 al Salon des Artistes Décorateurs (SAD), and communicated with the kitchen through a dumbwaiter set in a closet: two glass-and-steel shelves of clean lines that served as a buffet. The groundbreaking innovation was the dining table set on a retractable structure of chrome-plated tubular steel, with a wooden top covered with rubber, that could be extended to seat up to 11 people. Around it, swivel chairs and stools, a round table made of glass and stainless steel and a sculpture placed there as if by chance. Hypermodern forms, pioneering creations in years in which the dominant style of furniture was made of solid wood embellished with naiads and fauns.

Charlotte Perriand, Air France Agency, London, 1957. Photo: © Adagp, Paris, 2019 / Gaston Karquel / AChP.

The exhibition in Paris includes not just original drawings and photographs dug up from CP’s archives, but also real-size examples of her furniture: original pieces or reproductions, displayed in an extremely faithful setting created for the purpose. Anyone looking at it from close-up will experience the same emotion that Frank Gehry had when he entered CP’s home for the first time and discovered “her mastery of space and composition,” as he puts it in the preamble to the catalogue.5 “Everything was exquisitely composed at the human scale, immediate but not contrived. It was clear to me that she understood sculpture in the highest sense of the word, as the relationship between objects in the world. Moving through the modest space, I could feel the spaces as she had composed them. Everything had a purpose in a way that you can only do when designing for yourself.”6 The visitor will have the same sensation on entering the apartment presented at the Salon d’Automne in 1929 and perfectly reconstructed for this exhibition in a space accessible to the public: a new approach to dwelling that was the culmination of the program launched by Le Corbusier back in 1925, at the Pavilion of the Esprit Nouveau, with the intention of abandoning traditional modules in favor of bureaus, superimposable containers and a series of pieces of furniture made of steel, like the ones CP had already designed or would design, such as the Fauteuil grand confort and the Fauteuil à dossier basculant.

Charlotte Perriand, Fish Vertebra, 1933. Photo: © Adagp, Paris, 2019 / AChP.

But the extraordinary thing is that CP did not have to wait until her meeting with Le Corbusier to give vent to her creativity; it was long before then that she started to design pieces completely off her own bat. To be sure, the turning point came for her in 1927, when she read the Swiss architect’s two essays, Vers une architecture and L’art décoratif aujourd’hui, and had a revelation: “Those books made me see past the wall that was blocking my view of the future. So I took a decision: I was going to work with Le Corbusier.”7 But their first meeting was a disaster. She presented herself at no. 35 Rue de Sèvres, the studio that the Swiss architect and his cousin Pierre Jeanneret had set up in a long corridor that had formerly been the cloister of a Jesuit monastery (a building that was later demolished and replaced by a glass and concrete construction). She took out her drawings and when Le Corbusier asked her what she wanted, blurted out the only sentence she had prepared: “To work with you.”8 He looked her up and down through his round spectacles, glanced through the drawings and dismissed her with the words: “We don’t embroider cushions here.”9 Disheartened, the poor woman turned on her heel, but not before telling the genius about her Bar sous le toit on show at the Salon. These were not easy times for women: the world of architecture was peopled with extremely misogynous men. Charlotte felt herself to be a failure: she had not been able to get herself accepted. So it was a delightful surprise for her to find out, a few days later, that Le Corbusier had seen her furniture and was ready to let her join his studio to design the interiors of his new buildings. The mutual understanding between them in design would be so great that CP’s name would be overshadowed and even erased by Le Corbusier’s, and their collaboration would last for about ten years.

Le Corbusier, Le déjeuner près du phare, 1928. Photo: © Adagp, Paris, 2019 / Fondation Le Corbusier.

They were years of great complicity. The pair shared a passion for emptiness: “Vacuum is all potent because all containing,”10 as Taoism teaches us. But they would also be years filled with enthusiasms and jealousies, seeing that, after her divorce from the Englishman, Charlotte discovered Moscow and Berlin, founded an association of artists and had a love affair with Le Corbusier’s cousin and partner Jeanneret, forming a fruitful and complicated relationship with him. Together they would embark on research into art brut, studying with Fernand Léger the shapes of pebbles on the beaches of Dieppe, the fractals of fossils and the trunks of trees. And together they would make a break with Le Corbusier, before separating in the summer of 1940, when Charlotte left for Tokyo. Appointed, thanks to her friend, colleague and former intern Junzo Sakakura, an adviser on industrial design to the Japanese government, CP was supposed to stay in Japanese for just a year and a half to prepare a major exhibition. She was to remain there for six years, as the war upset her plans, separating her from Jeanneret and leading to her finding a new love, Jacques Martin, who would become her second husband and the father of her daughter Pernette. From that time on, the life of this infinitely resourceful girl from the mountains, a skilled skier and off-piste enthusiast, but also a lover of the sea and fanatic swimmer, would be an unending series of encounters and discoveries in which Cartesian rigor would be closely intertwined with an opening up to the world, with the study of non-European civilizations, in a continual process of renewal in order to try out new forms and unprecedented solutions.

Charlotte Perriand, La Maison de thé, 1993, reconstruction, 2019, Fondation Louis Vuitton, Parigi. Photo: © Adagp, Paris, 2019 / Fondation Louis Vuitton / Marc Domage.

It is necessary to see the whole of the exhibition in Paris, going through each of the nine galleries devoted to different periods of her life, in order to reconstruct all the passages, influences and mysterious threads that bind the years in Japan, with the discovery of the link between creativity and tradition, to her stay in Brazil, where she followed her husband, an Air France executive, to the design of the ski resort of Les Arcs in the seventies, 4500 apartments in the mountains of the Savoy facing onto Mont Blanc, and of the Tea House, a perfect symbol of the dialogue between cultures, a straw hut surrounded by a bamboo grove that she built at the headquarters of UNESCO in Paris for the Japanese Cultural Festival in 1993. On the other hand, back in Tokyo in the mid-fifties, CP had promoted the synthesis of the arts (architecture, furniture, objects of everyday use, tapestries, polychrome sculptures, wall hangings) in order to stage a major exhibition with the works of Le Corbusier, Fernand Léger and her own at the Takashimaya department store. Returning to Paris, she started to a produce furniture in partnership with the Galerie Steph Simon, taking on the market and distribution directly. Then she set off again for Rio de Janeiro, where she would enrich her language with new ideas, without ever forgetting her origins and her trademark, inventing new technological and industrial solutions, but united with a respect for nature, with her passion for the mountains and for water and the sea, which was the other side of her love for high altitudes. As if the challenge of inventing from scratch the art d’habiter in the 20th century could be met only by containing the force of technology and machinery, reining in industry so as to let nature breathe and to draw new lifeblood from it.

Charlotte Perriand: Inventing a New World

Curated by Jacques Barsac, Sébastien Cherruet, Gladys Fabre, Sébastien Gokalp and Pernette Perriand-Barsac.

Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris

October 2, 2019 – February 24, 2020

Le Corbusier, P. Jeanneret, C. Perriand, Chaise longue basculante, B306, 1928-29, Vitra Design Museum. Photo: © F.L.C. / Adagp, Paris, 2019 / Courtesy of Vitra Design Museum.

Charlotte Perriand, Sideboard, 1977. Photo: © Adagp, Paris, 2019 / MAD, Paris / Jean Tholance.

Charlotte Perriand, reception, 1955. Photo: © Adagp, Paris, 2019 / AChP.

Charlotte Perriand, furniture, Galerie Steph Simon, 1956. Photo: © Adagp, Paris, 2019 / Gaston Karquel / AChP.

Charlotte Perriand, Salle à manger 28, 1927. Photo: © Adagp, Paris, 2019 / AChP.

Charlotte Perriand, Travail et Sport, 1927-29. Photo: © Adagp, Paris, 2019 / AChP.

Charlotte Perriand, Stool, c. 1955. Photo: © Adagp, Paris, 2019 / Galerie Patrick Seguin.

Le Corbusier, P. Jeanneret and C. Perriand, Fauteuil grand confort, 1928.

Charlotte Perriand, Nuage bookcase, Steph Simon edition, c. 1958. Photo © Adagp, Paris, 2019 / Studio Shapiro / Galerie Downtown – François Laffanour.

Le Corbusier, Fernand Léger and Charlotte Perriand, Proposal for a Synthesis of the Arts, Tokyo, 1955; reconstruction, 2019, Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris. Photo: © Adagp, Paris, 2019 / F.L.C. / Fondation Louis Vuitton / Marc Domage.

Le Corbusier, Fernand Léger, Charlotte Perriand, Proposal for a Synthesis of the Arts, Tokyo, 1955; reconstruction, 2019, Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris. Photo: © Adagp, Paris, 2019 / Fondation Louis Vuitton / Marc Domage.

Charlotte Perriand, Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret, Un équipement intérieur d’une habitation, Salon d’automne, 1929; reconstruction, 2019, Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris, with the participation of Cassina and Sice Previt. Photo: Adagp, Paris, 2019 / Fondation Louis Vuitton / David Bordes.

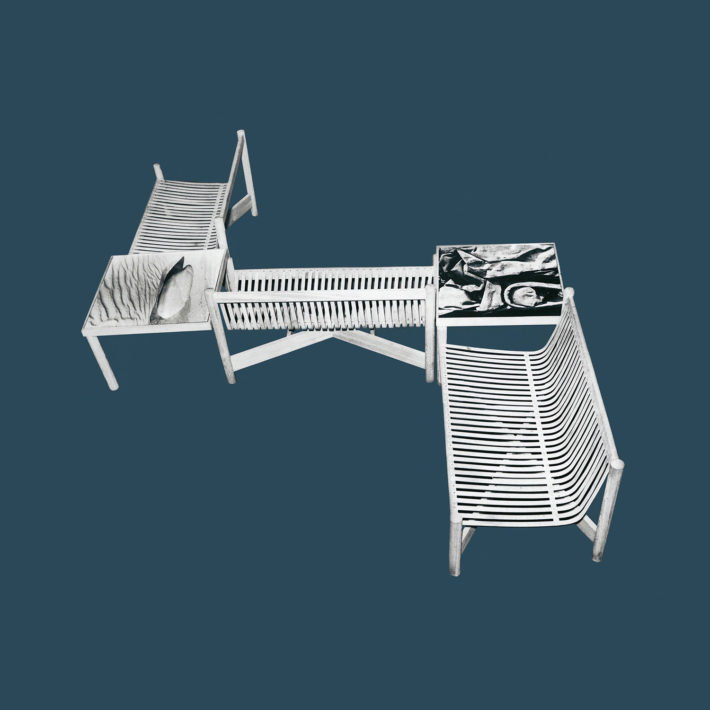

Charlotte Perriand, Méandre banquettes, composed of standard elements with wooden frame and seat and back made of bamboo strips, 1940. Photo: © Adagp, Paris, 2019.

Notes

1 Charlotte Perriand, Une vie de création, Editions Odile Jacob, Paris, 1998.

2 Sébastien Cherruet and Jacques Barsac (eds.), Charlotte Perriand: Inventing a New World (Paris: Fondation Louis Vuitton-Éditions Gallimard, 2019).

3 Sébastien Cherruet and Jacques Barsac (eds.), Charlotte Perriand: Inventing a New World, 72.

4 Charlotte Perriand, Une vie de création, 23.

5 Sébastien Cherruet and Jacques Barsac (eds.), Charlotte Perriand: Inventing a New World, 18.

6 Ibidem.

7 Charlotte Perriand, Une vie de création, 24.

8 Charlotte Perriand, Une vie de création, 25.

9 Ibidem.

10 Okakura Kakuzo, The Book of Tea (New York: Putnam’s, 1906), 16.