5 October 2018

There is a fascinating and controversial evolutionary theory that links the human race with water. According to this theory, in vogue in the 1960s,1 human beings are descended from a group of apes who were driven by a scarcity of food to move to the sea shore, where they could hunt for fish, mollusks and crustaceans. Obliged to spend a lot of time in the water, these apes adapted to their environment by becoming almost amphibian. This would explain why we are able to dive and swim and why we love water. Who knows? What must be true, instead, is the definition of ignorance given by the ancient Romans: a man who “neither knows how to read or swim.”2 Still in the Roman era, however, it seems, that “the more degenerate the emperor, the more sumptuous tended to be his Baths.”3 We are told this by Charles Sprawson, who has written a bestselling book on swimming, Haunts of the Black Masseur, and nothing since. After the thermae and public baths, places of intrigue, sex and care of the body, aquatic spaces devoted to recreation, sport and relief have assumed different forms and functions over the centuries: from architectural structures floating on rivers to swimming pools in the city, from Olympic-size pools to the iconic ones of California and the most sophisticated of contemporary infinity pools.

Deligny pool, Paris, 1950. © Keystone France and Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images.

In the mid-19th century, Milan boasted the luxurious Bagni Diana in the Porta Venezia area, built in 1842 by the architect Andrea Pizzala. The baths were demolished in 1908 to make room for the Hotel Diana, but were filmed by the brothers Auguste and Louis Lumière. On YouTube you can find the video Bains de Diane à Milan, from 1896, in which we see men diving—women were allowed access only at certain hours of the morning. For the mingling of the sexes we have to thank England, with its fashion for “lidos,” named after the famous Lido of Venice: open-air swimming pools equipped with bathrooms, changing rooms and a place to lie in the sun. In the thirties, Coco Chanel, who until just a few years earlier did not want to be mistaken for a sunburned peasant girl, changed her mind: being tanned was chic. But is it was not until after the war that sunbathing spread among the masses and costumes grew skimpier, passing from the scandalous one-piece swimsuit of Annette Kellerman—arrested for “indecency” in 1907—to the bikini introduced by Louis Réard, who gave up working on car engines to make a fortune devoting himself to women’s breasts.

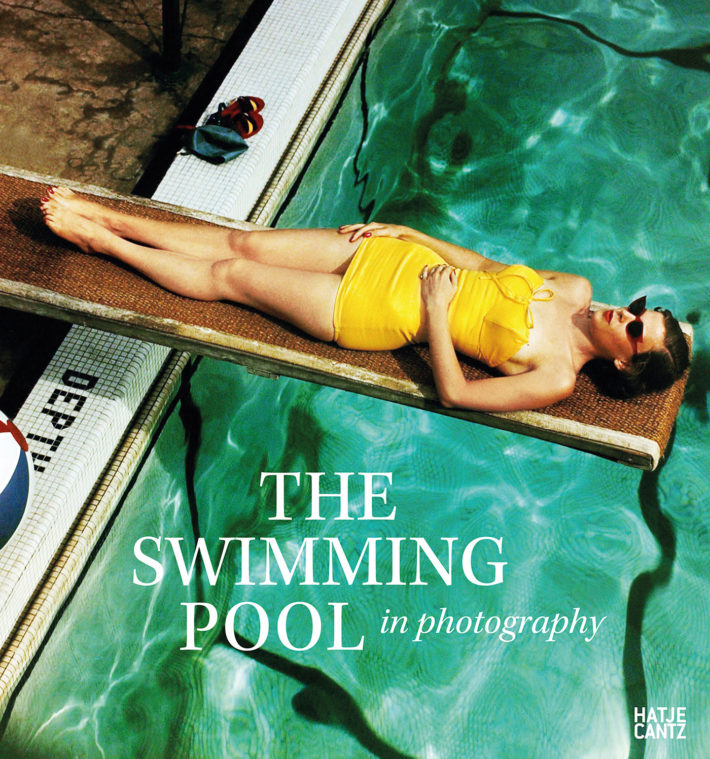

The Swimming Pool in Photography (cover) (Berlin: Hatje Cantz, 2018). © Hatje Cantz.

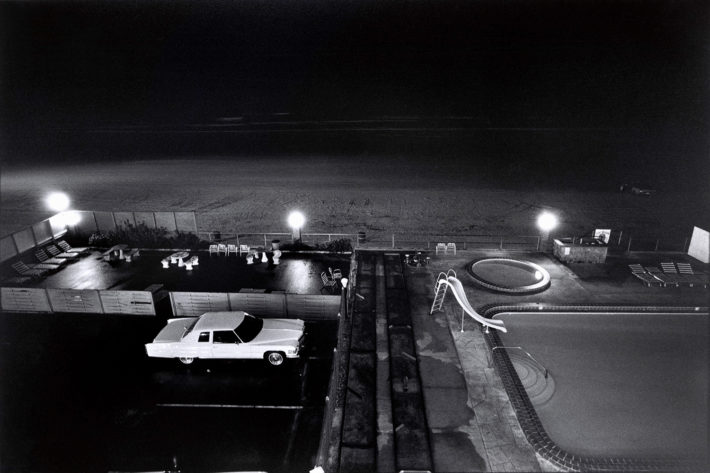

The swimming pool is not just a place for sportsmen and women or idle loafers, but one which has stories told about it everywhere. This is what Francis Hodgson says in the introduction to his The Swimming Pool in Photography,4 a fascinating volume brought out recently by Hatje Cantz. The fashion for lidos in the UK, we read in Ken Worpole’s Here Comes the Sun, reached its peak in the thirties, partly as a result of public funding: the new facilities were supposed to give jobs to the unemployed.5 The lido was an informal space that helped men and women meet one another other. Swimming and dancing were considered complementary recreational activities. In its issue of May 1936, CHUTE: The Magazine for Swimming, Sunbathing and Open-Air Recreation had a column entitled “Where to Swim and Dance,” a guide to lidos with live music and dancehalls. But it was in the United States that the swimming pool became a cult. The Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas concludes his Delirious New York6 with the story of a group of young Soviet architects who in the thirties, at the height of Stalinism, decide to flee their country: they arrive in New York, years later, aboard a floating swimming pool—that they designed themselves—capable of crossing the ocean. If you like America, you like swimming pools. For this we can blame David Hockney’s pictures, Joan Didion who always wanted one and the “aquamusicals” with Esther Williams. Along with California and its water crises: surrounded by desert, its inhabitants dreamed of private oases, and created them. And it was there that the custom of skateboarding in empty and abandoned pools developed in the seventies. If you think about it, Frank Perry would not have been able to shoot The Swimmer (1968) in Rome. In the film, based on the short story by John Cheever published in The New Yorker in 1964, Burt Lancaster decides on a hot summer’s day to swim his way home across the county, passing from one backyard pool to another, from one house to another, on a journey that brings to light his personal failures and the cracks in the American dream.

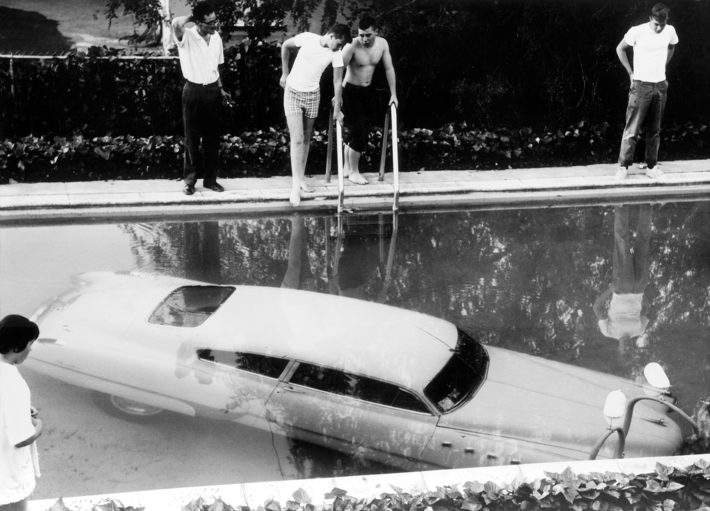

Car parked in swimming pool, Beverly Hills, California, May 4, 1961. © Keystone and Getty Images.

You can come to a sticky end in swimming pools: “The poor dope. He always wanted a pool. Well, in the end he got himself a pool—only the price turned out to be a little high…”: this is what the deceased Joe Gillis, played by William Holden, says in the opening scene of Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1950), observing himself floating fully dressed and face down in the swimming pool of the film star Norma Desmond, promising to tell us the whole truth before it is distorted by Hollywood columnists. Sixty years later, Skyler, the wife of Walter White, the chemistry professor in the unforgettable TV series Breaking Bad, jumps fully dressed into the swimming pool, in the midst of a nervous breakdown. Walter is unable to reconcile the two faces of the American dream: domestic happiness and financial security. Either one or the other. And the swimming pool is there to remind him of it, reflecting his failures; first bogus financial ease, then destruction of the family equilibrium. What used to be a status symbol (having enough money and time to allow yourself a pool), now completes the picture of the standard American family, along with wife, children, SUV and dog. It is no longer a mark of success, at least in the United States. To rediscover the connotation of exclusivity it is not necessary to go to the infinity pool of the Four Seasons in the Seychelles or the one on the rooftop of Marina Bay Sands in Singapore, all you need is a renovated farmhouse in Tuscany with no Wi-Fi: the height of luxury is no longer just having free time, but being able to spend it offline.

The corpse of Joe Gillis (William Holden) floating in the swimming pool of the villa belonging to Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson) in Sunset Boulevard, 1950, directed by Billy Wilder. © AF Archive/Alamy Stock Photo.

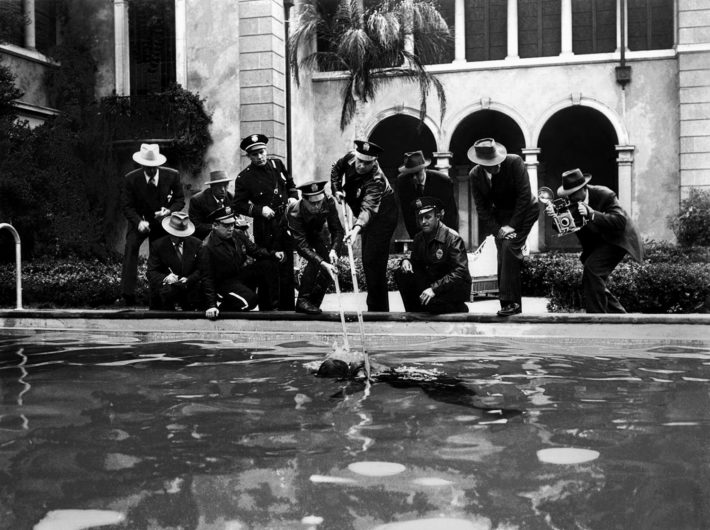

Not to insist on drama, but in the movies the association between corpses and swimming pools is one that has been around for a long time: from The Alphabet Murders (1965) to The Day of the Locust (1975) and Dario Argento’s Suspiria (1977), where “a lot of strange, absurd things” happen. In the dystopian future of Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville: une étrange aventure de Lemmy Caution (1965), people sentenced to death are executed in a swimming pool. In another dystopian future, the one depicted in Elio Petri’s The 10th Victim (1965), Marcello Mastroianni tries to kill Ursula Andress by arranging for her to be eaten by a crocodile in a swimming pool, turning the idea of an artificial space that protects against the perils of nature on its head. And if you have seen Cat People, whether Jacques Tourneur’s version (1942) or Paul Schrader’s (1982), you will know that it’s not a good idea to take a dip at night, even in a swimming pool. In order not to end up swimming in the pool of corpses in Dario Argento’s Phenomena (1985), the water has to undergo processes of coloring, disinfection and thermoregulation. By a variety of means: chlorine, bromine, electrolysis of salt or UV sterilization. Otherwise, without bactericides, all it would take is a class of schoolchildren to pollute a swimming pool and turn it into a bacteriological bomb—remember what Michael Phelps admitted to the Wall Street Journal in 2012: “I think everybody pees in the pool.” Never mind the brats. And it’s not just a matter of keeping the water clean. There are fungi, germs, verrucas. And warm water, which as well as being a bad habit and a tiresome concession to children and the elderly, is ruinous for the health: its ideal for bacteria. At this point better a crocodile on the bottom than swimming in a neglected pool.

USA. Florida. 1975. Photo: Elliott Erwitt. © Elliott Erwitt/Magnum Photos.

Of course, water is also source of life and realm of passions: the pool can be the lover’s bed for Baz Luhrmann’s William Shakespeare’s Romeo + Juliet (1996) or the catalyst of erotic tensions in Jacques Deray La Piscine (1969). In The Springboard in the Pond, an essay on the theme by the historian of architecture Thomas A.P. van Leeuwen, we read: “[…] since America, including Hollywood, is emphatically puritanical and therefore hypocritical, the introduction of the swimming pool as a pretext to show nude or seminude bodies was a spectacular opportunity. Eros could be shown in an athletic and hygienic context, providing legal as well as tasteful entertainment for the voyeur as family man.”7 On the edge of the swimming pool—or nearby—seduction can be more or less explicit: Tara Reid certainly is so with Jeff Bridges in The Big Lebowski (1998) by the Coen brothers, offering to suck his cock for 1000 dollars. In George Cukor’s Something’s Got to Give (1962), the last movie Marilyn Monroe appeared in before her death, the star goes for a swim in the nude, inviting Dean Martin to join her in the pool, but Dean doesn’t accept and she dries herself. Marilyn had lived for years at the Beverly Carlton Hotel in Beverly Hills, which used to have a pool in the shape of a figure of eight that was photographed by Loomis Dean in 1954.

Faye Dunaway at the Beverly Hills Hotel on the morning of March 29, 1977, the day after winning the Oscar for Best Actress in Network, 1976, directed by Sidney Lumet. Photo: Terry O’Neill. © Terry O’Neill/Iconic Images/Getty Images.

Celebrities and swimming pools, a classic. One of the best pictures in the book published by Hatje Cantz is by Terry O’Neill: it was taken in 1977, portrays Faye Dunaway and is part of a series. We’ll come back to it later, first let’s look at O’Neill: a British jazz drummer, he dreamed of working as an air steward on flights between London and New York, which would have left him more free time to become a famous musician; he applied, but there were no openings and so he fell back on the job of a photographer at Heathrow airport—as he himself recounts. It turned out to be the right move. In the sixties and seventies he photographed them all: the Rolling Stones, the Beatles, Brigitte Bardot, Audrey Hepburn, Marianne Faithfull, Liz Taylor, David Bowie, Elton John, his friend Frank Sinatra. And Faye Dunaway. She is the protagonist of a memorable group of photos taken on March 29, 1977, the day after she won the Oscar—the one for Best Actress in Network. O’Neill was not looking for the usual portrait with the statuette, he wanted to capture the moment in which its winner realized that her career had reached a turning point; the moment after which everything would be multiplied: money, fame, prestige, offers of roles. O’Neill put his idea to Faye Dunaway, she agreed and at 6 in the morning of that March day she got up to have herself immortalized on the set of the Beverly Hills Hotel, with the swimming pool behind her, newspapers on the ground and the signs of a sleepless night on her face. Languid, absorbed, beautiful. In one of the shots she is smiling, and it is the smile of a woman who loves the person she is looking at. Terry and Faye would marry in 1983.

Esther Williams in a scene from the film Million Dollar Mermaid, 1952, directed by Mervyn LeRoy. © Getty Images

Pools are for swimming, and diving. This is something that Esther Williams knew all too well. First a champion swimmer and then a Hollywood actress, she broke her neck and risked being paralyzed for life because of the costume—a very heavy crown—in which she took a dive in Million Dollar Mermaid (1952), a biopic about the aforementioned Annette Kellerman, an Australian swimmer famous all over the world both for her talents in the water and because she was the first to wear a one-piece bathing suit, stirring a great scandal. In a photo in The Swimming Pool in Photography we see Esther smiling into the camera, suspended above a pool in which, arranged in a radial pattern, some thirty men and women are waiting for her. Even horses dive, or almost. Francis Hodgson speaks8 of the attractions of Atlantic City, where horses were thrown into the swimming pool, as in the photo taken by Barbara Laing in 1991, in which a mule drops from an 18-foot-high diving platform into a pool at the World’s Only High-Diving Mules Show in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Today the society for the prevention of cruelty to animals would have something to say. Diving in photography crosses political barriers. There is the Soviet artist Alexander Rodchenko’s Dive (1934), and there is the work of Leni Riefenstahl, a controversial filmmaker and photographer who was an excellent swimmer in addition to being close to the Nazi regime. Then there are the athletes: the British champion Betty Slade, Johnny Weissmuller, in a picture taken at Brighton Beach in New York, where he broke the hundred meter record with a time of 1.17 seconds, and Blandine Fagedet, winner of the female diving contest at the Georges-Vallerey swimming pool in Paris. But the most ambitious project was Aaron Siskind’s: his Pleasures and Terrors of Levitation, made between the fifties and sixties, is one of the most important photographic studies of the practice of diving.

Pleasures and Terrors of Levitation #37, 1953. Photo: Aaron Siskind. © Aaron Siskind Foundation.

Martin Parr, that brilliant chronicler of common sense, has also immortalized the swimming pool, in his own way. His pictures have the peculiarity of spoiling our appetite (the series entitled Real Food is a sort of stomach pump in reverse) or taking away any desire to go on vacation (Global Tourism could be an ad for the prevention of skin cancer) or even to visit a swimming pool. Let’s take The Last Resort (1983-85), the series that made him famous in which he documented the working class at play during the Thatcher era at New Brighton, near Liverpool: a child having its nappy changed on the ground, squeezed by its anxious mother, or left to itself in a high chair under the sun, near the putrid water. White trash before this became a question of identity. We are in the mid-eighties, a time when cultured reportage was still done in black and white; but Parr loved color, had the Americans Stephen Shore and William Eggleston in mind and in addition used the flash, which gave a touch of hyperrealism to his pictures. In one of The Last Resort’s photos there are two young people in the foreground snuggling on a bench, and in front of them—because the picture is taken from behind—a crowd of bathers lying on large slabs of asphalt: it looks like the swimming pool of the Reichssportfeld at the summer Olympics of 1936, in Berlin, photographed by Lothar Rübelt. Except that we are not in the Third Reich: the weather is fine, the day is hot and people are having a good time. The only one who seems to have noticed the camera is a blond boy, right at the center of the frame. He has his back to the swimming pool and is looking in the opposite direction to everyone else—perhaps he would like to be somewhere else. And we wonder if that child knows how to swim, and if his parents think the same way as the ancient Romans: you don’t want to stay ignorant, do you?

Panoramic pool on the roof of the Cité Radieuse, the celebrated housing development designed by Le Corbusier and built between 1947 and 1952, in Marseille. © Pixabay.

Swimming pool designed by Alain Capeilleres at Le Brusc, France. Photo: Martine Franck, 1976. © Martine Franck/Magnum Photos.

Woman at swimming pool, 1950s, USA. Photo: H. Armstrong Roberts. © Getty Images.

Blandine Fagedet, winner of the female diving contest at the Piscine Georges-Vallerey in Paris, July 13, 1962. © Keystone France and Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images.

Notes

1 The theory was popularized by the marine biologist Alister Hardy, who on March 17, 1960, published an article in the New Scientist entitled “Was Man More Aquatic in the Past?” It was later taken up and built on by the writer Elaine Morgan through a number of books, but has never been fully accepted by the scientific community.

2 Charles Sprawson, Haunts of the Black Masseur: The Swimmer as Hero (London: Cape, 1992), 49.

3 Ibidem, 46.

4 The Swimming Pool in Photography, text by Francis Hodgson (Berlin: Hatje Cantz, 2018), 7-9.

5 Ken Worpole, Here Comes the Sun: Architecture and Public Space in Twentieth-Century European Culture (London: Reaktion Books, 2000), 113.

6 Rem Koolhaas, Delirious New York: A Retroactive Manifesto of Manhattan (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1978).

7 Thomas A.P. van Leeuwen, The Springboard in the Pond: An Intimate History of the Swimming Pool (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1998), 159.

8 The Swimming Pool in Photography, 35.