22 February 2019

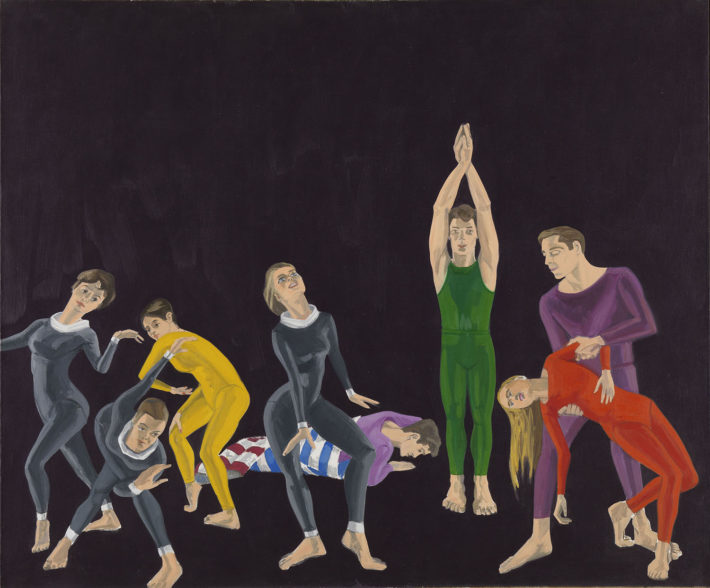

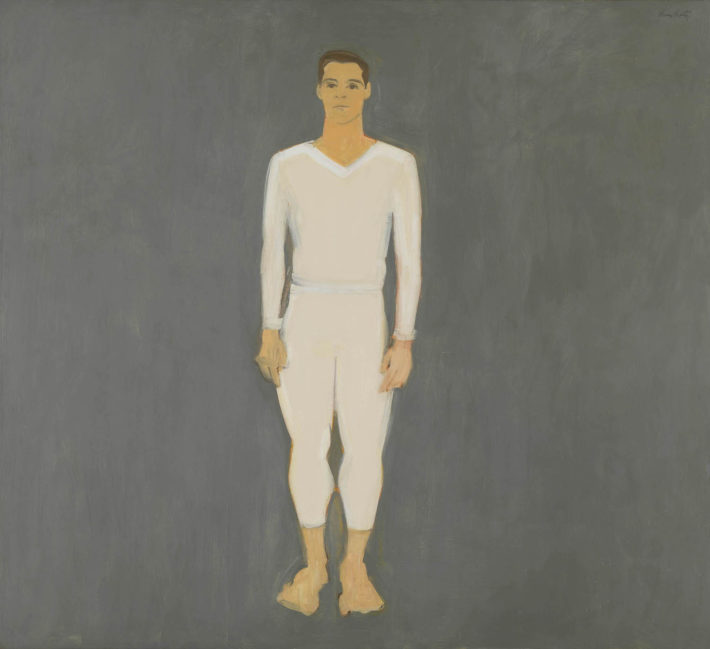

Alex Katz is one of those artists who put a strain on the categories into which historians try to pigeonhole the protean flow of art. Born in New York in 1927, fifteen years after Jackson Pollock and just one before Andy Warhol, he could be considered the link between two generations of American painting: that of Abstract Expressionism and that of Pop Art. And yet today, in 2019, Katz continues to paint his large and enigmatic pictures sixty-three years after the death of the inventor of dripping and thirty-two after that of the Pope of Pop. And he is not just a survivor from the golden age of American art: his work retains its freshness, untouched by the passage of time. It suffices to look at the large pictures on display in a recent exhibition at the Timothy Taylor Gallery in London, entitled Coca-Cola Girls: they have the vitality of paintings straight out of the studio of a young artist. It’s hard to say what elixir of eternal youth he draws his inspiration from, but the best way to enter his world is probably to visit the retrospective curated by Jacob Proctor that the Brandhorst Museum in Munich is devoting to him in these months (running until April 22). Over ninety works, including large and small canvases, cutouts and sketches, drawn chiefly from the magnificent collection of Udo and Anette Brandhorst (he is still alive, but she died in 1999). The presence of around twenty of Katz’s works among the acquisitions of the refined German patrons (who over the years have amassed the most important collection of Cy Twombly’s paintings in Europe as well as over a hundred works by Andy Warhol), tells us a great deal about the popularity of the artist from New York. In Munich it is possible to retrace the entire span of the American painter’s output, from the 1950s to the 2010s, including such emblematic pictures as The Black Dress (1960), Paul Taylor Dance Company (1963-64), Winter (1996) and Grey Coat (1997).

Alex Katz, Coca-Cola Girl 36, 2018, oil on linen. © Alex Katz/DACS, London/VAGA, New York, Courtesy Timothy Taylor, London/New York. Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates.

The story of Alex Katz, going by his own words, has been that of a continuous misunderstanding on the part of the critics and the public. “They’re always putting me in a context I don’t belong to,”1 he declared in an interview granted to Donald Kuspit at the beginning of the nineties: “I make big heads, so people think I’m a Pop artist. They think I’m a weak solution to the Pop problem. That’s wrong. I’m not dealing with Pop issues.”2 On the other hand, he continues: “Because I wasn’t an Abstract Expressionist, they thought I have no depth, nothing to do with the unconscious, as thought it could be articulated only one way, through one style.”3 The painter has never concealed his admiration for the great exponents of the New York School, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Franz Kline and Willem de Kooning: the world at the time lay at their feet. No one had the same force, the same energy, powerful enough to shift the center of the art world from the rubble of old Europe to the maze of Manhattan’s skyscrapers. It was the beginning of the fifties. Katz looked at what was going on and understood, but didn’t want in. He couldn’t go along with what had by then almost become a dogma: an image for modern times could only be an abstract one. When he started to work—his first show was in 1954—Edward Hopper was still fully active, but it seemed clear that that kind of figuration belonged to the past. The young Alex knew that, if he wanted to keep playing in the field of figurative painting, he would have to go in quite another direction. And so he started to develop “a representational art that’s really physical,”4 as he explained to Constance Lewallen in 1991: “It’s a modern idea, in terms of picturemaking, and that’s what I set out to do. Because people were saying representation is obsolete, I set out to find how to make it part of the modern world.”5

Alex Katz, Winter, 1996, oil on canvas. © Alex Katz, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018, Courtesy Udo and Anette Brandhorst Collection. Photo: Haydar Koyupinar, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich.

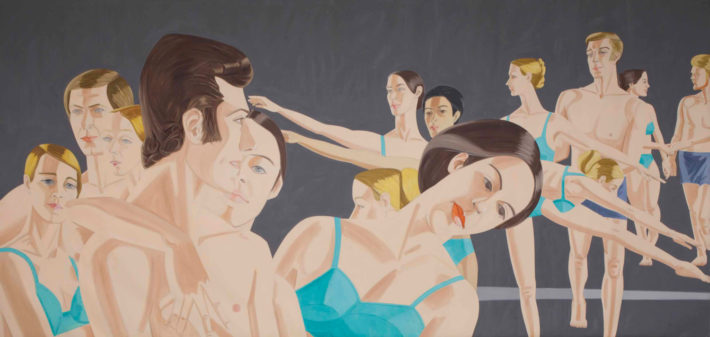

It was an uphill struggle, and the reason why is clear: recognizable subjects, as in old-style figuration, combined with the monumental scale introduced by the New York School. As the years passed Katz’s style began to take shape: the human figure or figures stand out against uniform backgrounds (like Édouard Manet’s The Fifer), without any attempt at narration. Sometimes the subject is repeated one or more times (his wife Ada, in The Black Dress, is replicated six times). And perhaps the genre of the group portrait is the one that most intensely reflects the unsettling character of Katz’s painting. This is most evident in works like Lawn Party (1965) and like Private Domain (1969), with the majesty of its six-meter-width, included in the exhibition at the Brandhorst. For his Italian debut at the Galleria Emilio Mazzoli, in 1990, Achille Bonito Oliva wrote: “The American artist has created a sort of oblique realism, aimed at the attainment of a clear and precise vision, a focus and a point of view that draw on the perspective of photography and the cinema.”6 At the center of Katz’s pictures lies not “the materialist ecstasy of Pop Art, the static survey of things, but a movement of dematerialization and cropping that decontextualizes the image and makes it the sole protagonist of the framing.”7 The idea of cropping was to play a leading role in the series of cutouts,8 where the figures are removed from their backgrounds and placed on freestanding structures. The background no longer exists. “The figure is portrayed in the peace and quiet of an everyday action,” continued the Italian critic: “shifted from the all-encompassing plane of its existence into the artificial and isolated one of art, where what is at work is the selectivity of an attention that purifies space and time and lays the foundations for the vision of a new physical and mental image, fruit of an intertwining of manual skill and intense intellectualism.”9 There can be no doubt that for Katz painting is a mental thing. Even though his cultural references seem to diverge from the ones that underpinned the period of Abstract Expressionism. Many have pointed out the parallels between his painting and the atmosphere of cool jazz. Drawing on Herbert Hellhund’s analysis of the musical genre that emerged in New York between the fifties and sixties, the German art historian Jochen Poetter has detailed its characteristics: “Emotionally controlled or indifferent, lacking moral commitment, smart, attentive, focusing on the essentials.”10 And again: “Tasteful, aesthetically attractive, intellectual.”11 All qualities that can well be applied to Katz’s painting and with which he himself identifies: “That was jazz, something hot done in a cool way. I prefer Stan Getz to Sartre, I get my stylization from Getz, not from some overphilosophized existence.”12

Alex Katz, The Black Dress, 1960, oil on canvas. © Alex Katz, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018, Courtesy Udo and Anette Brandhorst Collection. Photo: Haydar Koyupinar, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich.

And when it comes to “something hot done in a cool way” in painting it is hard not to think of Piero della Francesca, and it was precisely to the painter from Sansepolcro that David Sylvester made reference in a long interview recorded in 1997. Katz confirmed the insight: “I liked Piero a lot in the early fifties and actually I kept trying to get a Fulbright [the Fulbright Scholar Fellowships in Fine Arts, editor’s note] to go to Italy to see his paintings. I love the Baptism in the National Gallery. The details in the background seem so brand-new-looking, like someone could have done it today. I like his casting of characters.”13 For Katz, Piero was able to bestow a “static quality” on the gestures of his figures, a characteristic that he also finds in the works of Jacques-Louis David, where the gestures are “very very clear”14 and “very decisive.” And he goes on to say: “I am very conscious of trying to make gestures very clear.” Take, for example, Grey Coat (1997): the full-length figure of Ada, Katz’s wife and muse, wrapped in a gray coat, is set against a uniform dark green ground. The woman is seen in profile and with her head turned to the left, looking at the viewer. Her arm is bent at a right angle and her hand seems to be resting gently on her stomach. The folds of the coat appear frozen, not by the cold of New York but by the freeze-frame of a video recorder (this was the nineties). The eyes are brown. There are a few streaks of white in her gray hair. Her shiny lipstick reflects light coming from who knows where. The figure occupies the left-hand half of the picture, the rest is an empty expanse of green. Ada, a now mature woman whose charm has remained untouched by time, almost in the image of her husband’s painting, is plainly aware of being observed from outside the picture. We don’t know where she’s coming from. Nor do we know where she is or where she is going. All we see is her frosty image. What we are looking at struggles to stir precise questions in us and is clearly unable to answer the few that do arise. Oscar Wilde would probably have described her as a “sphinx without a secret.”15

Alex Katz, Red Hat (Alba), 2013, oil on canvas. © Alex Katz, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018, private collection. Photo: Andreas Pauly.

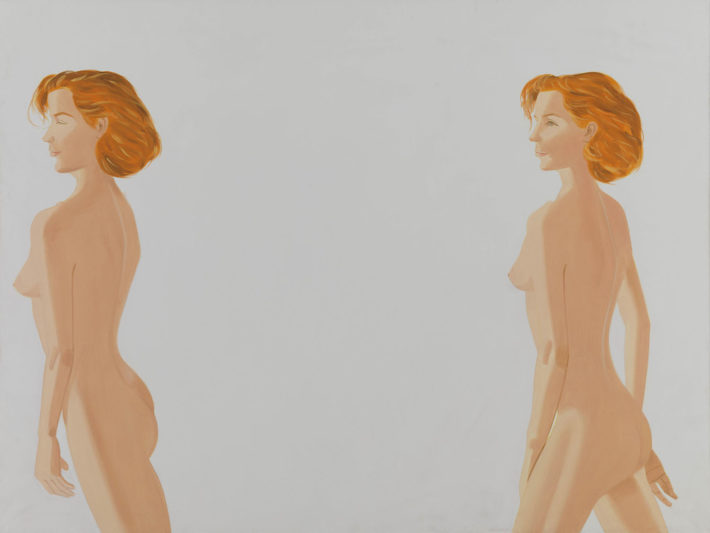

The mistake we should not make when looking at one of Katz’s works is to believe that what we see is something other than mere painting. And this is true for both the portraits and the landscapes. The pictures do not have a particular person as their subject (significantly, Katz often refers to the portraits as “heads”), nor do they depict a precise landscape in Maine (where, since 1954, he has had a second studio that he uses during the summer). It is as if the subject presented were simply the means through which he arrives at painting and a bait with which to lure the viewer. “It could be a pretty girl, or it could be something else,” says Katz. “What you think you are looking at could be one thing, but it keeps changing.”16 There is no interest in psychology or sociology, the attention to detail has more to do with a taxonomical study17 and with the contemplation of beauty: “Because you live in the city where there is a value on elegance and beauty and that’s like one of the things I’m involved with. I think some people find it hard to accept that as being art—elegance and beauty—they want to see social messages, suffering, inner expression, all of those things which I’m not interested in.”18 The artist has concentrated on representing the precise shade of color or the texture of the hair or skin and, above all, their relationship with the light. And it is on the representation of light that David Sylvester dwells, lamenting the inability of printed reproductions to convey the greatness of Katz’s works.19 And it is the artist himself who insists on the preeminence of painting over the subject portrayed (“Ultimately, content is not important. The style is what is important”)20 and admits: “I can’t think of anything more exciting than the surface of things.”21 Perhaps it is this lack of interest in narrative content that has saved Katz’s work from getting bogged down in the manner of so much figurative painting of the 20th century, which at a distance of years appears, with a few extraordinary exceptions, so dated. Over the course of his career, the artist from New York has moved in the direction of an increasing simplification of the composition, accompanied by an ever growing attention to the manner of execution. The classical quality of these images, the way they belong to that free zone in which figurative painting and conceptual art are able to coexist, suggests a comparison of the American artist with a painter who has won over the hearts of the custodians of painting for painting’s sake as well as the minds of devotees of the avant-garde: Giorgio Morandi. Katz shares with him the universal dimension, the sense of mystery, the remote metaphysical aura. These are the elements of his art, an art whose low temperature has slowed down the entropy of a talent that, in the long run, has stood up to the passage of time.

Alex Katz

Curated by Jacob Proctor

Museum Brandhorst, Munich

December 6, 2018-April 22, 2019

Alex Katz, Private Domain, 1969, oil on linen. © Alex Katz, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018, Courtesy Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, London / Paris / Salzburg. Photo: Charles Duprat.

Alex Katz, Red Nude, 1988, oil on canvas. © Alex Katz, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018, Courtesy Udo and Anette Brandhorst Collection. Photo: Haydar Koyupinar, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich.

Alex Katz, Grey Coat, 1997, oil on canvas. © Alex Katz, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018, Courtesy Udo and Anette Brandhorst Collection. Photo: Haydar Koyupinar, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich.

Alex Katz, Flowers 3, 2011, oil on board. © Alex Katz, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018, private collection. Photo: Andreas Pauly.

Alex Katz, Big Wave, 2001, oil on board. © Alex Katz, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018, private collection. Photo: Andreas Pauly.

Alex Katz, January 4, 1992, oil on linen. © Alex Katz, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018, Courtesy Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, London / Paris / Salzburg. Photo: Ulrich Ghezzi.

Alex Katz, Moonlight, 1997, oil on canvas. © Alex Katz, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018, Courtesy Udo and Anette Brandhorst Collection. Photo: Haydar Koyupinar, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich.

Alex Katz, 3 p.m. November, 1996, oil on canvas. © Alex Katz, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018, Courtesy Udo and Anette Brandhorst Collection. Photo: Haydar Koyupinar, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich.

Alex Katz, Ives Field 1, 1964, oil on canvas. © Alex Katz, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018, private collection.

Alex Katz, Paul Taylor Dance Company, 1963-64, oil on canvas. © Alex Katz, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018, Courtesy Udo and Anette Brandhorst Collection. Photo: Haydar Koyupinar, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich.

Alex Katz, Paul Taylor, 1959, oil on canvas. © Alex Katz, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018, Courtesy Udo and Anette Brandhorst Collection. Photo: Haydar Koyupinar, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich.

Alex Katz, Emma 4, 2017, oil on canvas. © Alex Katz, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018, Courtesy Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, New York / Rome, private collection.

Notes

1 Donald Kuspit, Alex Katz. Night Paintings (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1991), 64; quoted by Kevin Power in “Pleasant decorous days of chatter: Alex Katz in the company of poet-friends,” published in Alex Katz, ed. Vittoria Coen, catalogue of the exhibition at the Galleria Civica di Arte Contemporanea, Trento, November 21, 1999-January 16, 2000 (Turin: Hopefulmonster, 1999), 130.

2 Ibidem.

3 Ibidem.

4 Constance Lewallen, “Interview with Alex Katz,” View, VII, no. 5 (1991), 5; quoted by Margrit Brehm in “Art by nature,” published in Coen, ed., Alex Katz, 52.

5 Ibidem.

6 Achille Bonito Oliva, “Il realismo obliquo di Alex Katz,” in Alex Katz (Modena: Galleria Mazzoli, 1990); English trans., “The oblique realism of Alex Katz,” published in Coen, ed., Alex Katz, 34.

7 Ibidem.

8 Matt Saunders, “The Cutouts,” in Alex Katz: Painting the Now, ed. Jacob Proctor, catalogue of the exhibition at the Museum Brandhorst, December 6, 2018-April 22, 2019 (Munich: Hirmer, 2018), 38-40.

9 Achille Bonito Oliva, in Coen, ed., Alex Katz, 34.

10 Jochen Poetter, “Something Hot Done in a Cool Way. On the Syncopated Compositions of Alex Katz,” in Robert Storr, Margrit Brehm and Jochen Poetter, Alex Katz: American Landscape (Staatliche Kunsthalle, Baden-Baden, 1995); text published in Coen, ed., Alex Katz, 100.

11 Ibidem.

12 Ibidem, 98.

13 David Sylvester, “Interview with Alex Katz,” in David Sylvester and Merlin James, Alex Katz. Twenty Five Years of Painting (London: The Saatchi Gallery, 1998); text published in Coen, ed., Alex Katz, 192.

14 Ibidem.

15 “The Sphinx Without a Secret” is a well-known short story by Oscar Wilde, published in 1887, about “a woman with a mania for mystery,” in which a photograph of her face is described as having a “beauty moulded out of many mysteries.”

16 “Alex Katz interviewed by David Salle,” in Alex Katz: Unfamiliar Images, texts by Enzo Cucchi and Vincent Katz (Milan: Alberico Cetti Serbelloni Editore, 2002), 15; Kirsty Bell quotes from the interview in “It Could Be a Pretty Girl, or It Could Be Something Else,” in Proctor, ed., Alex Katz. Painting the Now, 11.

17 Ibidem, 12.

18 David Sylvester, “Interview with Alex Katz,” published in Coen, ed., Alex Katz, 200.

19 David Sylvester, “Introduction,” published in Coen, ed., Alex Katz, 166.

20 “Alex Katz: ‘Ultimately, content is not important. The style is what is important,’” Studio International (October 23, 2017).

21 Calvin Tomkins, “Painterly Virtues, Alex Katz’s life in art,” The New Yorker, August 27, 2018. “Ignoring character and mood, he offered the pure sensation of outward appearance—not who the people were, but how they appeared at a specific moment. ‘I can’t think of anything more exciting than the surface of things,’ he later told an interviewer.”