29 June 2020

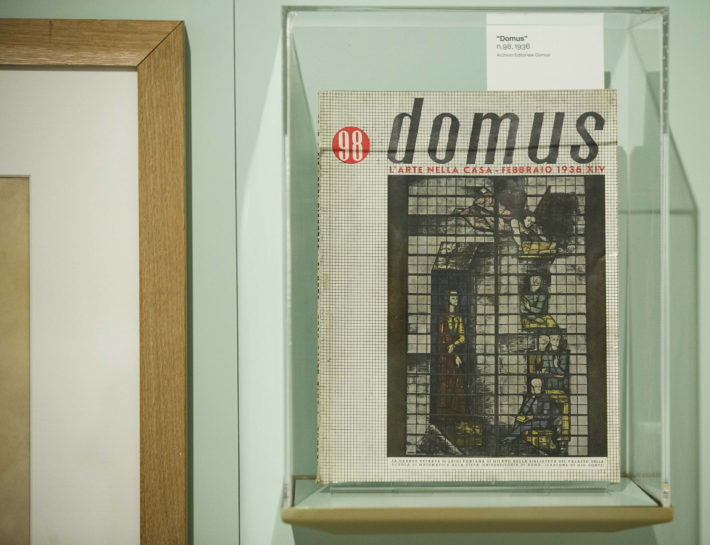

If God is in the detail, then the spirit of Loving Architecture, the exhibition that the MAXXI Museo nazionale delle arti del XXI secolo has devoted to Gio Ponti, extended until September 27 following its temporary closure as a result of the pandemic, can be summed up in the words framed on the fourth floor of the museum in Rome designed by Zaha Hadid. Set in a rectangle so small it almost escapes notice is the letter that another great architect, Adalberto Libera, wrote to Ponti about the drawing his colleague had commissioned from him for the cover of his magazine, Verso la casa esatta. A letter that contains a whole world: “As you have taken the amicable trouble to tell me in two letters that the cover is no good, it must really be very bad […]. But you are a better judge than I am. I have no experience in publishing. Do as you like and I have no doubt that I will be completely satisfied.” The architect and the publisher, the designer and the editor, the poet and the critic. The particular and the universal. When, after many years have passed and we have made our peace with the word, we are perhaps going to find out what we should have always known, that Gio Ponti was the first, the greatest and very likely the only true influencer that Italian architecture has ever had. And this is due not so much to his talent as a designer as to his ability to break down the process into all its facets (like those of a crystal, which not coincidentally Ponti saw as the perfect metaphor for architecture) in a multiplicity of moments and aspects that ranged from the project itself to its communication, in a single flow of beauty.

Gio Ponti, Taranto Con-Cathedral, Taranto, 2019. Photo: © Delfino Sisto Legnani. Courtesy: Fondazione MAXXI.

A year after Tutto Ponti at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, the exhibition at the MAXXI curated by Maristella Casciato and Fulvio Irace takes stock of the most versatile and fascinating figure in our architecture, our design and perhaps the whole world of “Made in Italy.” So many-sided was he, in fact, that even the title Loving Architecture, borrowed from Ponti’s manifesto Amate l’architettura, a book published in 1957 which achieved cult status before going out of print and returning to the bookstores in 2008 in a Rizzoli edition, appears reductive. For, as is clear from the way the exhibition has been organized, Ponti’s lesson is that everything is design, and so it is not just his architecture we should love but also his industrial design, along with his photography, his books and his magazines. Today we would say that we ought to love his communication.

Loving Architecture, then, but also this exhibition made up of archive materials, models, photographs, publications and classics of product design like the Superleggera chair for Cassina or the washbasins for Ideal Standard, closely linked with Ponti’s architectural projects and organized into eight sections that evoke the architect’s key concepts. The exhibition pays homage to Ponti and tries in its turn to be Pontian, in other words immersive, fluid and colorful, greeting the visitor in the lobby of the MAXXI with an installation of banners made of Alcantara, hanging in the spaces that run the full height of Zaha Hadid’s building. Reproducing stylized façades of skyscrapers, they call to mind the skyline of a Pontian city that we have never seen. Emerging from the elevators that lead to the exhibition rooms, visitors find the linoleum flooring that Ponti dubbed giallo fantastic, or “fanciful yellow,” used to cover the ramp and taking them straight into the Pirellone, the skyscraper he designed in Milan. And even before entering the gallery, Thomas Demand’s photographic project depicts the models of vertical buildings conserved at the Study Centre and Communication Archive (CSAC) of Parma University, present in the exhibition. Inside the gallery, a giddy display of models, reproductions and images that, from Villa Planchart in Caracas to the Pirelli Tower, passing through the Co-Cathedral of Taranto, lead to the inevitably Instagrammable part of the display: a sitting room à la Ponti, with the designer’s armchairs, coffee table, lamps and movable partitions looking onto the profile of the Pirellone and leading the visitor’s gaze out, toward the view of Rome through the glass wall of the museum.

Gio Ponti, Taranto Con-Cathedral, Taranto, 2019. Photo: © Delfino Sisto Legnani. Courtesy: Fondazione MAXXI.

An exhibition that is a continual challenge, and that, just as Ponti’s Amate l’architettura was “a book not on architecture but for architecture,” sets out to be an exhibition not on architecture but for architecture, not on design but for design. A show that becomes the three-dimensional representation of a redemption and that, to borrow the words of Salvatore Licitra, Ponti’s grandson and curator of the exhibition in Paris last year, gives the lie to the analyses that in the past have presented Ponti as “an eclectic opportunist lacking cultural integrity,”1 clearing the field of the studies that, “according to the taste or interest of the writers, consider ‘dominant and significant’ one ‘genre’ rather than another.” We have had to wait for the times of interdisciplinarity, of cultural fluidity—Licitra even speaks of the “cultural changes engendered by digital technology”—in order to make “a unified analysis of his work, focused on perception, both natural and understandable.”2

Here the flatware for Christofle, the ceramics for Marazzi, the door handles for Olivari, the washbasins for Ideal Standard, the Superleggera chair for Cassina and the model of his design for the Diamante car, together with the grand works of architecture, tell a unique story, that of a man who by reason and instinct saw himself as the ambassador of a culture in which architecture, art and design became one and the same thing. There are also the images of the furnishings3 for the first-class cabins on the Conte Grande and the Andrea Doria (1950-1952) and the prestigious settings of the Conte Biancamano (1950), enriched with the ceramics of artists like Melotti, Fontana, Melandri and Leoncillo: “In the 1950s, years of recovery and renewal, collaboration with artists became the utopia of a synthesis of the arts, which had a tangible example in naval furnishings,” where Ponti followed, as Paolo Campiglio explains, the principle by which “the interiors of ships constitute a sort of floating museum, an emblem of Italian creativity in the world, with unfailing recourse to tradition”; whence the abundance of “themes from mythology or folklore, like playing cards and masks.”4 And then the apartments in Milan, designed for himself or his daughters, conceived as stage sets for the furniture of Ponti himself and Mollino, the decorations of Fornasetti, the ceramics of Melotti, the paintings of De Pisis and Funi, and later Albers, Wirkkala’s glassware, Noguchi’s big spherical lamps and finally, at the time when he had developed a passion for contemporary art, the works of Gilardi, Merz, Paladino, Luciano Fabro, Prini and others.

Gio Ponti, Palazzo Liviano, Padua, 2019. Photo: © Giovanna Silva. Courtesy: Fondazione MAXXI.

But, once again, we would not be able to understand Ponti fully if we did not go beyond the strict limits of design. “Ponti knew that—just as was being done by the people at Olivetti in Italy and their counterparts on the other side of the Atlantic (the Eameses first and foremost)—a plan of communication is a powerful sounding board for the idea intrinsic to the product itself,”5 writes Domitilla Dardi in an essay in the exhibition catalogue that offers perhaps the best summary of Ponti’s figure, “Art Direction in Italian Design.” “His experience as an editor of major magazines was put to the service of the company, although he did not use it for publishing polished advertising, but instead for a real editorial product, a corporate publication with the company name as its title, accompanied by the subheading: ‘Summary of the problems of wellbeing.’ This was a stroke of genius: it wasn’t just about products, indeed it had very little to say about them, but instead talked about a right to mental, intellectual, and aesthetic wellbeing, as well as physical wellbeing.”6

Ponti had a similar awareness of the role of photography, to the point where he felt compelled to write in Domus as early as 1932, as Roberto Dulio recalls in another essay in the catalogue, that “photography needs to be used artfully; this artfulness means knowing how to ‘achieve’ with photography what we already see in and understand about things: but that is not all. The independence of the photographic view in itself has also and once again revealed to us an unknown side to things, it has given us a new sense of them and a new way of interpreting the images.”7 Dulio explains that such an “acute awareness of the use of photography and its implications, along with the interest that Ponti always harbored for art, publishing, fashion, advertising, could only lead to the honing of a sophisticated strategy of visual communication. Long before the use of photography, the images […] were what paged the ideas suggested by tradition in taste—actually: style, as Ponti himself would say—that was absolutely modern.”8 And in fact “Domus’s success in the postwar years, […] was due to the fact that it was a magazine where the photography counted more than the text. Large images and short texts, and it was much appreciated around the world,”9 said Lisa Ponti. Perhaps, though, what was truly miraculous about Ponti was that the Milanese architect did not arrive at this awareness through theory, as the curator Fulvio Irace points out.10 It was Ponti himself who said that “my mind is not naturally predisposed for the determination of principles, for the designing of theories,”11 but for individual action. What we still lack today, more than many other things.

Gio Ponti. Loving Architecture

Curated by Maristella Casciato and Fulvio Irace, with Margherita Guccione, Salvatore Licitra and Francesca Zanella.

MAXXI Museo nazionale delle arti del XXI secolo, Rome

November 27, 2019—September 27, 2020

Gio Ponti. Loving Architecture, view of the exhibition at the MAXXI, Rome, 2019-20. Photo: © Musacchio, Ianniello & Pasqualini. Courtesy: Fondazione MAXXI.

Gio Ponti. Loving Architecture, view of the exhibition at the MAXXI, Rome, 2019-20. Photo: © Musacchio, Ianniello & Pasqualini. Courtesy: Fondazione MAXXI.

Gio Ponti. Loving Architecture, view of the exhibition at the MAXXI, Rome, 2019-20. Photo: © Musacchio, Ianniello & Pasqualini. Courtesy: Fondazione MAXXI.

Gio Ponti. Loving Architecture, view of the exhibition at the MAXXI, Rome, 2019-20. Photo: © Musacchio, Ianniello & Pasqualini. Courtesy: Fondazione MAXXI.

Gio Ponti. Loving Architecture, view of the exhibition at the MAXXI, Rome, 2019-20. Photo: © Musacchio, Ianniello & Pasqualini. Courtesy: Fondazione MAXXI.

Gio Ponti. Loving Architecture, view of the exhibition at the MAXXI, Rome, 2019-20. Photo: © Musacchio, Ianniello & Pasqualini. Courtesy: Fondazione MAXXI.

Gio Ponti. Loving Architecture, view of the exhibition at the MAXXI, Rome, 2019-20. Photo: © Musacchio, Ianniello & Pasqualini. Courtesy: Fondazione MAXXI.

Gio Ponti. Loving Architecture, view of the exhibition at the MAXXI, Rome, 2019-20. Photo: © Musacchio, Ianniello & Pasqualini. Courtesy: Fondazione MAXXI.

Gio Ponti. Loving Architecture, view of the exhibition at the MAXXI, Rome, 2019-20. Photo: © Musacchio, Ianniello & Pasqualini. Courtesy: Fondazione MAXXI.

Gio Ponti, School of Mathematics, Rome, 2019. Photo: © Stefano Graziani. Courtesy: Fondazione MAXXI.

Gio Ponti, School of Mathematics, Rome, 2019. Photo: © Stefano Graziani. Courtesy: Fondazione MAXXI.

Gio Ponti, Hotel Parco dei Principi, Sorrento, 2019. Photo: © Allegra Martin. Courtesy: Fondazione MAXXI.

Gio Ponti, Hotel Parco dei Principi, Sorrento, 2019. Photo: © Allegra Martin. Courtesy: Fondazione MAXXI.

Gio Ponti, Montecatini Building, Milan, 2019. Photo: © Michele Nastasi. Courtesy: Fondazione MAXXI.

Gio Ponti, Montecatini Building, Milan, 2019. Photo: © Michele Nastasi. Courtesy: Fondazione MAXXI.

Gio Ponti, Taranto Con-Cathedral, Taranto, 2019. Photo: © Delfino Sisto Legnani. Courtesy: Fondazione MAXXI.

Gio Ponti, Palazzo Liviano, Padua, 2019. Photo: © Giovanna Silva. Courtesy: Fondazione MAXXI.

Notes

1 Salvatore Licitra, “Gio Ponti: Houses Like Me,” in Gio Ponti. Loving Architecture, ed. Maristella Casciato and Fulvio Irace, catalogue of the exhibition of the same name at the MAXXI Museo nazionale delle arti del XXI secolo, Rome (Florence: Forma Edizioni, 2019), 50.

2 Ibidem.

3 Paolo Campiglio, “Ponti. An Artist among Artists,” in Gio Ponti. Loving Architecture, 99.

4 Ibidem.

5 Domitilla Dardi, “Art Direction in Italian Design,” in Gio Ponti. Loving Architecture, 222.

6 Dardi, “Art Direction in Italian Design,” 222-23.

7 Gio Ponti, “Discorso sull’arte fotografica,” in Domus, no. 53 (May 1932), 285-88, cited by Roberto Dulio in “‘Nihil est in intellectu quod non fuerit in sensu’: Photography Between Art and Communication,” in Gio Ponti. Loving Architecture, 286.

8 Duilio, “‘Nihil est in intellectu quod non fuerit in sensu’,” 286.

9 Lisa Ponti’s words are quoted in A. Maggi, “The Italian Dream: Giorgio Casali, Domus and Design Photography,” in A. Maggi and I. Zannier, eds., Giorgio Casali Photographer/Domus 1951-1983: Architecture, Design and Art in Italy, catalogue of the exhibition of the same name at the Centro Internazionale Scavi Scaligeri, Verona, February 16-May 15, 2013; Estorick Collection of Modern Art, London, June 26-September, 2013 (Cinisello Balsamo, MI: Silvana Editoriale, 2013), 49-61, the quote is on p. 51. Reproduced here from Dulio, “‘Nihil est in intellectu quod non fuerit in sensu’,” 287.

10 Fulvio Irace, “Architecture as Crystal. From the Closed Form to the Articulated Plan,” in Gio Ponti. Loving Architecture, 165.

11 Gio Ponti, “Invenzione di un’architettura composta. Dai ‘cuboni’ alla composizione di un’architettura,” Stile, no. 39 (1944), cited by Irace, “Architecture as Crystal,” 165.