28 November 2018

In his recent essay, The Game, Alessandro Baricco takes on the task of imparting order to the digital revolution that is changing the nature of our society at such a dizzy speed. To do so, he says that he is ready to renounce complexity from the start: “We are too much in need of a legible synthesis to waste much time in the cult of precision.”1 That Baricco really wants to renounce complexity is not entirely true, and the same could be said of Sanguine: Luc Tuymans on Baroque, the imposing exhibition curated by Tuymans at the Fondazione Prada, which will run until February 25. It is a show that sees in the duality of simple/complex a stimulus for the interpretation of a hypertrophied and hyperconnected contemporary world. Tuymans’s too is an attempt to decipher reality through reductio ad unum, i.e. the search for a minimum common denominator, in this case the baroque, that unites the 17th century and the age in which we live. First staged at the Festival of the Baroque in Antwerp which opened last June, Tuymans’s exhibition has moved to Milan, where it is being presented on an even grander scale: it comprises, in fact, 80 works by 63 artists, 25 of them created exclusively for the buildings in Milan and many intended to be site specific and to hold a dialogue, through affinities and contrasts, with their location. Above and beyond historiographical approaches and critical interpretations, the Belgian artist is convinced that the peculiar artistic climate of the 17th century had anticipated much of what we have become today: the exaggerated image, the propensity for the erotic and violent, the emotional and moral wringing and the fideistic propaganda, if not the populism. A common thread, in short, that runs through twists and turns from Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (1647-52) to augmented reality, from Caravaggio’s The Cardsharps (1594) to the social media, from the colonnade of St. Peter’s to sovereigntism.

Luc Tuymans at the Fondazione Prada, Milan. Photo: Ugo Dalla Porta. Courtesy Fondazione Prada.

Active since the early eighties, Tuymans contributed to the reappraisal of the European canons of painting and then went on to experiment with different art forms, always in search of an up-to-date and pregnant meaning. This is not the first time he has ventured into politics, having already tackled themes like the Holocaust (two of his father’s brothers had been members of the Hitler Youth) or colonial crimes in the Belgian Congo. In September 2002, perhaps in reaction to the attacks of the September 11, 2001, he felt the need to play down the reference to current affairs, proposing a gigantic still life measuring five by four meters at documenta11: the result was more political than many other avowedly engaged proposals. Even today, with a past as a bouncer and security guard (it appears that, at the age of nineteen, he was dazzled by the sight of a series of El Greco paintings that he was had to keep an eye on in Budapest), he has not lost a degree of pragmatism, unusual for an artist of his importance and reputation: “It’s certainly not this artist’s finest work, but it’s the one that we were able to get hold of,” he would say several times while accompanying us on our visit to Sanguine. He describes the baroque era as “a transition”:2 what better definition could be found for our present? The reasons for his attraction to this era are evident from the selection of works, never based on dogma. If we are more or less all agreed on the fact that the baroque period, between the end of the 16th century and the early part of the 18th, was one in which classical rigor exploded into a jumble of volumes, compositions and sceneries, fusing the most extreme realism with a masterly illusionism and making itself the vehicle of an agonizing reflection on matters of life, passion and death, it is also true that it has not been easy to come to a unanimous verdict on its value. One of the first to define it, the Dictionnaire de Trévoux of 1771 described the baroque taste as something in which “the rules of proportion are not observed, where everything is represented according to the artist’s whim.”3 It would not be until the 19th century and to an even greater extent the postmodern era that we would come to appreciate the baroque rhapsody in all its liberating force.

Willem de Rooij, Bouquet IX, 2012. Photo: Szymon Rogiński. Courtesy Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne / New York.

Tuymans starts out from this situation of uncertainty and proposes a selection through which runs a subtle strand of ambiguity, at times of irony, picking out the most daring aspects of the baroque. Because if the exhibition includes works by undisputed masters like Rubens, van Dyck and Zurbarán, it is their almost random juxtaposition with those of contemporary artists that creates an unprecedented sense of vertigo. Thus we find defined as baroque here Mark Manders’s imposing plaster heads that have been cut in half (Room with Unfired Clay Figures, 2011-15), as well as the deceptive light of Pavel Büchler’s Eclipse (2009) or the African hyperrealism of Cheikh Ndiaye’s Cinéma Rio Lakota (2017). The game, a refined and perilous one, is precisely this: thematic cues, signs of modernity and at the same time of historicity, could be found in all the artistic expressions of the last few decades. At the beginning of the exhibition, for instance, we immediately come across a large vase of fresh white flowers, Bouquet IX (2012) by the Dutch artist Willem de Rooij, that encompasses many indications: illusion, decay, theatricality. The attention to detail, to anatomy and to nature, represented at its most ripe, a moment prior to fading, was a must of the 18th century, stemming from the scientific revolution and the demystification of death (“Death, be not proud, though some have called thee / Mighty and dreadful, […] / Thou art slave to Fate, Chance, kings, and desperate men,”4 wrote John Donne in those years).

Berlinde De Bruyckere, In Flanders Fields, 2000. Collection M HKA (Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp) / Collection Flemish Community, Antwerp.

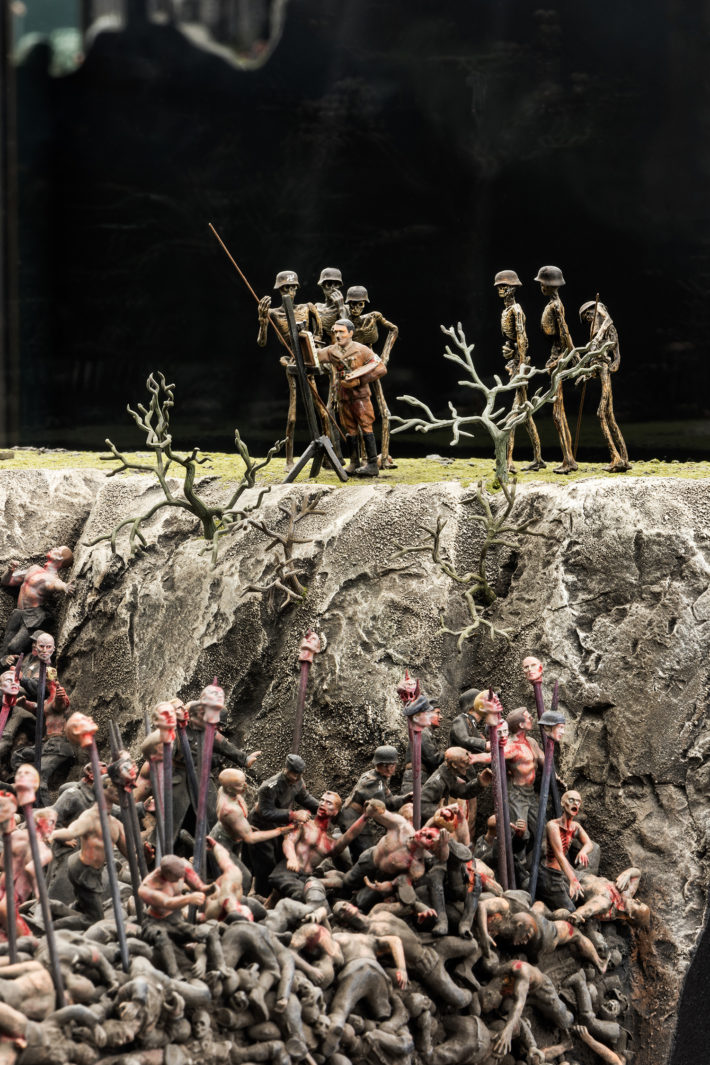

Besides, life and death are linked by very fine threads: Berlinde De Bruyckere’s stuffed horses (In Flanders Fields, 2000), also a metaphor for the horrors of the First World War, or Marlene Dumas’s sorrowful portrait of a Dead Girl (2002), are examples of a violence that is not even particularly sublimated but fairly explicit (apropos of this, Tuymans should be given credit for having found room for a large number of female artists). Violence also holds sway in Edward Kienholz’s Five Car Stud (1969-72), which stages the brutal castration of a black man by a gang of white men (the work, seen by Tuymans right here at the Fondazione Prada, in 2016, is proposed again in the exhibition through a film made by Alex Salinas). Another outstanding piece in this sense is Fucking Hell (2008) by Jake and Dinos Chapman, a sort of diorama of human atrocity in which thousands of tiny plastic figures represent Nazis, their victims and pigs. A grim, apocalyptic theater, teeming with horrors and prodigious in its accuracy, almost an extreme form of modeling: clearly baroque contrasts that continue to bolster the dual spirit of Sanguine. Dual in a manner of speaking, for in reality this exhibition has multiple faces, all of which are summed up in the reflections of Carla Arocha and Stéphane Schraenen’s Circa Tabac (2007), in which disjointed mirrors capture fragments of the surrounding works to great scenic effect.

Marlene Dumas, Dead Girl, 2002. LACMA (Los Angeles County Museum of Art), purchased with funds from the Buddy Taub Foundation, Jill and Dennis Roach, directors (M.2003.1). © 2018 Digital Image Museum Associates / LACMA / Art Resource NY / Scala, Florence.

There are numerous contributions that work on the semiconscious threshold of opposites: freedom and oppression, purity and indelicacy, gigantism and minutiae, but above all falsehood and truth. It takes a while to realize that the little girl wandering around an abandoned restaurant in Fukushima in Pierre Huyghe’s video Untitled (Human Mask), of 2014, is in reality a monkey wearing a mask and a wig. Or that Javier Téllez’s Nosferatu (The Undead), of 2018, interpolates the classic horror movie of 1922 with modern interviews and other contributions to reflect on mental illness as a horrific connotation of our times. Or again, that the reassembled statues of Nadia Naveau, a brilliant linkup of rococo and Disney, speak of a syncretism between past and present. This interplay of diverted perceptions and unfulfilled expectations is perhaps the most successful move in Tuymans approach to exhibiting. And yet we are inclined to think that the biggest attractions of the whole show are the two Caravaggios that the curator is proud to have been able to lay his hands on: the Boy Bitten by a Lizard (1596-97) and the David with the Head of Goliath (1609-10), located almost at random along the route, are mesmerizing in the way that they suggest everything there is to say on the baroque of yesterday and today. And looking at other masterpieces from the period that have been included the suspicion arises that this where the real contemporary narrative is to be found: Jacob Jordaens’s Erichthonius Discovered by the Daughters of Cecrops (1617) is a manifesto against fat shaming; Guido Cagnacci’s The Death of Cleopatra (1660-62) has been ready, since the second half of the 17th century, to end up as a meme; A Porter, dressed as a humble worker and posed as a distinguished aristocrat, is the image that Adriaen Brouwer would have posted if Instagram and its ennobling make-believe had existed a few centuries ago. But above all Caravaggio: the resistance to conformist public opinion, the rebellion against a simplifying authority, the expression of a marginality that fixes what will be the canon of posterity. Caravaggio is like punk, like vaporwave, as subversive as fact checking.

Jake Chapman and Dinos Chapman, Fucking Hell, 2008. Image of the exhibition Sanguine. Luc Tuymans on Baroque, Fondazione Prada. Photo: Delfino Sisto Legnani and Marco Cappelletti. Courtesy Fondazione Prada.

Back in 1987, in his essay Neo-Baroque: A Sign of the Times, the semiologist Omar Calabrese looked precisely to the age of Bernini, Borromini and Guarini in order to make sense of a decade, the fabulous eighties, that comprised Roland Barthes and Tinto Brass, the tragedy of the Heysel Stadium and the Italian TV variety show Drive In, the pop aesthetics of Michael Jackson and the success of the Riace Bronzes, Eco’s labyrinth and Deleuze’s rhizome. A time, that is, which in his view was characterized by “a loss of entirety, totality and system in favor of instability, polydimensionality, and change.”5 A bit like what goes on in our own day, in which what dominates, to borrow again the words of Baricco with which we began, is “the sensation of having been thrust out of the known world, and of having started to colonize areas of ourselves that we had never explored and in part have not even generated yet.”6 The exhibition Sanguine seems to reassert the same fear of disorientation and so resorts to the same, familiar category of the past. In other words, Tuymans finds in baroque propaganda, in its ecstatic and bombastic images, in its violent, vital and viral temperament, all the harbingers of what is happening today: “populism, the search for the easy and emotional reaction of the public,”7 fake news and so on. In short, the baroque is pretext and refuge: every time the world loses its borderlines, its immediate recognizability, every time the rules of the game change, the only symbol able to represent it seems to be the baroque pearl. The baroque can be everything and nothing, it is precise but vague as well, it frightens and reassures. A bit like our own age.

Sanguine: Luc Tuymans on Baroque

Curated by Luc Tuymans

Fondazione Prada, Milan

October 18, 2018 – February 25, 2019

From left to right: Guido Cagnacci, The Death of Cleopatra, first half of the 17th century, Caravaggio, Boy Bitten by a Lizard, 1596-97. Image of the exhibition Sanguine. Luc Tuymans on Baroque, Fondazione Prada. Photo: Delfino Sisto Legnani and Marco Cappelletti. Courtesy Fondazione Prada.

In the foreground: Jake Chapman and Dinos Chapman, Fucking Hell, 2008. In the background, from left to right: Michaelina Wautier (attributed to), Portrait of Two Girls as Saints Agnes and Dorothy, 17th century, Anthony van Dyck, Portrait of the Artist Marten Pepijn, 1632. Image of the exhibition Sanguine. Luc Tuymans on Baroque, Fondazione Prada. Photo: Delfino Sisto Legnani and Marco Cappelletti. Courtesy Fondazione Prada.

Pierre Huyghe, (Untitled) Human Mask, 2014. Image of the exhibition Sanguine. Luc Tuymans on Baroque, Fondazione Prada. Photo: Delfino Sisto Legnani and Marco Cappelletti. Courtesy Fondazione Prada.

In the foreground: Carla Arocha and Stéphane Schraenen, Circa Tabac, 2007. In the background, from left to right: Njideka Akunyili Crosby, When the Going Is Smooth and Good, 2017, Jacob Jordaens, The Daughters of Cecrops Finding the Child Erichthonius, 1617. Image of the exhibition Sanguine. Luc Tuymans on Baroque, Fondazione Prada. Photo: Delfino Sisto Legnani and Marco Cappelletti. Courtesy Fondazione Prada.

Carla Arocha and Stéphane Schraenen, Circa Tabac (details), 2007, courtesy the artists, and Johann Georg Pinsel, Saint John the Apostle and Our Lady (detail), 1758, courtesy Lviv National Gallery, Ukraine. Photo: Alex Salinas, 2018.

Johann Georg Pinsel, Mourning Madonna (detail), 1758, Lviv National Art Gallery.

Mark Manders, Room with Unfired Clay Figures, 2011-15. Image of the exhibition Sanguine. Luc Tuymans on Baroque, Fondazione Prada. Photo: Delfino Sisto Legnani and Marco Cappelletti. Courtesy Fondazione Prada.

From left to right: Cheikh Ndiaye, Cinéma Rio Lakota, 2017, Nadia Naveau, Roi, je t’attends à Babylone, 2014, Zhang Enli, Inane, 2016. Image of the exhibition Sanguine. Luc Tuymans on Baroque, Fondazione Prada. Photo: Delfino Sisto Legnani and Marco Cappelletti. Courtesy Fondazione Prada.

Peter Paul Rubens, Lamentation over the Dead Christ with Saint John and the Holy Women, 1614. Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp. © Lukas-Art in Flanders VZW. Photo: Hugo Maertens.

In the foreground: Carla Arocha and Stéphane Schraenen, Circa Tabac, 2007. In the background: Caravaggio, David with the Head of Goliath, 1609-10. Image of the exhibition Sanguine. Luc Tuymans on Baroque, Fondazione Prada. Photo: Delfino Sisto Legnani and Marco Cappelletti. Courtesy Fondazione Prada.

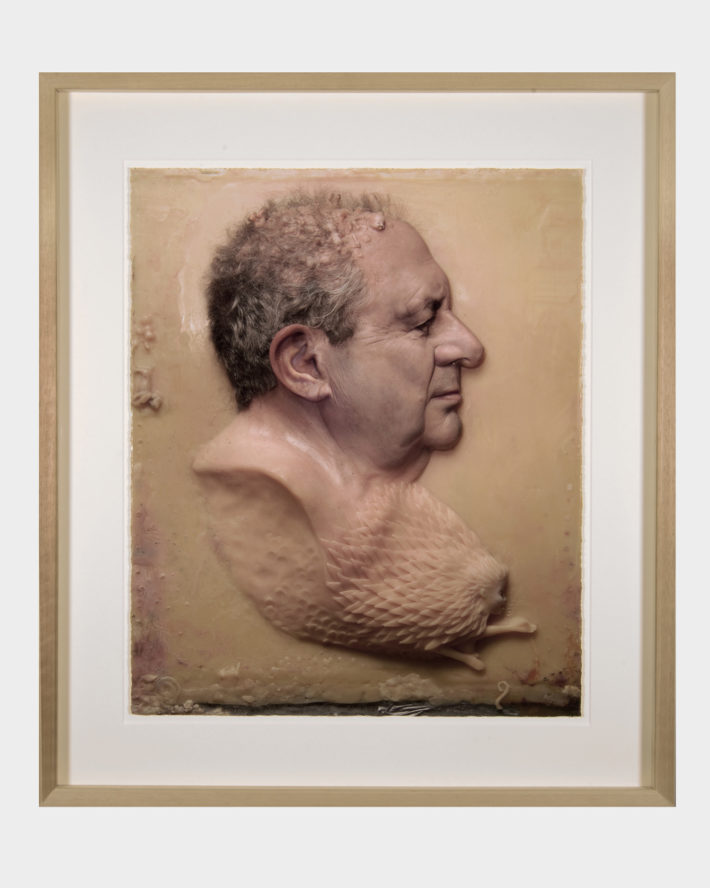

Roberto Cuoghi, Megas Dakis, 2007, private collection.

Kerry James Marshall, Vignette #2.75, 2008. Art Institute of Chicago. © 2018 The Art Institute of Chicago / Art Resource, NY / Scala, Florence.

Notes

1 Alessandro Baricco, The Game (Turin, Einaudi, 2018), 47.

2 “Luc Tuymans: Il barocco? Siamo noi,” interview conducted by Dario Pappalardo, La Repubblica (October 19, 2018).

3 “Baroque,” in Jésuites et imprimeurs de Trévoux, Dictionnaire universel françois et latin, 6th ed., vol. 1 (1771), 770.

4 John Donne, Selected Writings (Oxford-New York, Oxford University Press, 2018), 157.

5 Omar Calabrese, L’età neobarocca (Rome-Bari, Laterza, 1987), vi. English translation by Charles Lambert, Neo-Baroque: A Sign of the Times (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992), xii.

6 Baricco, The Game, 14.

7 “Luc Tuymans: Il barocco? Siamo noi.”