6 March 2020

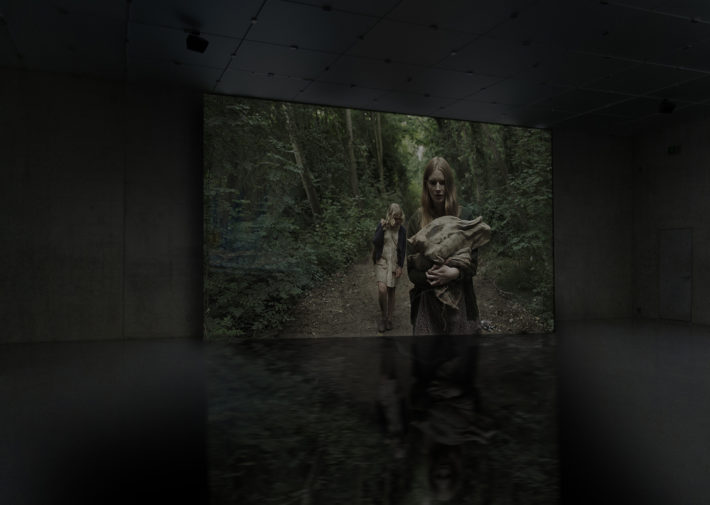

The Israeli artist Gili Lavy is known for her large-scale video projections that probe the relationship between places, individuals and beliefs. It is no accident that Lavy favors sites steeped in history as locations for her works. From November 6 to December 8, 2019, under the auspices of the BAM (Biennale Arcipelago Mediterraneo), Lavy returned to show in Palermo, a city she is fond of and one that has an age-old history of cultural stratification. Her works had already been exhibited in the Sicilian capital in 2017, during the Festival of Migrant Literature, to be specific at Palazzo Chiaromonte-Steri, the former seat of the Spanish Inquisition. On this occasion, however, the venue was the former monastery of La Magione, built by the last Norman king at the end of the 12th century in the old Arab quarter of the Kalsa. We met Gili Lavy in another former religious house, the convent of Santa Caterina d’Alessandria, where for over seven centuries Dominican nuns lived a cloistered life, secluded from the rest of the world: a place with an authentic atmosphere, opened to the public for the first time in 2017 and close to the themes tackled by the artist in her video installation La mère divine (The Divine Mother).

Let’s start with La mère divine (2015), one of your most widely viewed works and shortlisted in 2017 for the Mario Merz Prize in Turin.

It is a dual-channel video installation shot in Ratisbonne Monastery, in Jerusalem, the city where I was born and raised, and in which four faiths and many beliefs coexist. The monastery has always held a great fascination for me. Every day, on my way to school, I used to pass through the grounds of this place and my curiosity was stirred by such an iconic religious institution. Today I realize that my interest stemmed in part from its location in the heart of Jerusalem, next to the first Jewish girls’ school in Israel, a synagogue and the Artists’ House Gallery, built by a wealthy Arab in the 1880s. It was founded in the 19th century by a Jew who had converted to Catholicism and has undergone a series of transformations up to the present day: it was first turned into an orphanage, then the headquarters of an Austrian artillery regiment during the First World War, a hostel for pilgrims and today, finally, the campus of the Department of Theology of the Salesian Pontifical University. It is one of the many exceptional sites that can be found in Jerusalem, built before it became the capital of Israel.

Gili Lavy, La mère divine, dual-channel moving-image installation, still from video, 2015. Courtesy of Gili Lavy.

In La mère divine we see the daily lives of some women in a religious institution, a routine made up of prayers, chants and frugal meals.

Yes, viewers find themselves watching the protagonists in a state of complete devotion, practically in thrall to religion. I wanted to show women on their journey of faith and mourning, in a phase in which there is no longer hardly any inner quest concerning the meaning of the place or these feelings. At the root of my research there is a question: what do certain rituals signify in themselves? I also wanted to investigate the transitions that have been made in the establishment over the centuries, both as a place of worship and as a refuge in a land that was undergoing religious and territorial changes, altering perspectives, modifying rituals and bringing into question the classical structures of thought.

Your installations often show groups of individuals isolated from the world. Can you tell us why?

One of the themes of my research is migration, not just in the traditional sense, but as representation of a constant movement, of mutability, of uprooting and in general of reality understood as the most precarious of mental perceptions. In particular, one concept I work on is “post-trauma,” that is to say the period of time that follows a dramatic event or a catastrophe. I tend to focus on this specific moment, only hinting at what has happened and concentrating on the consequences, on what is left or what has gone. The groups of protagonists of my installations often find themselves outside their environment and overcome by a feeling of extraneousness. They have in common a sense of disorientation that oppresses them and a daily existence made up of quasi tribal rituals; their interactions call to mind situations that are often real, sometimes constructed.

Do you think there are similarities, from the cultural viewpoint, between Palermo and the city of your birth?

I would say so. I have a magical relationship with Palermo. I had the privilege of discovering its charm in 2017, on the occasion of my solo exhibition at the Palazzo Chiaromonte-Steri, curated by Agata Polizzi and the Fondazione Merz. The Mediterranean mentality, the markets, the street life, the heat and above all the mixture of identities, cuisines, cultures and histories, all this makes Palermo and Jerusalem unique cities. Jerusalem is built on four different religions, with four different quarters; Palermo is built around four main markets. In addition, even though in very different ways, both cities have been places of terror, and I believe they have much in common in terms of trauma and survival. Jerusalem and Palermo are the product of migrations and the combination of different cultural identities: Arab, Jewish, Spanish, Greek and still others. This is also reflected in my research, and it is partly for this reason that Palermo interests me.

Jewish children evacuated from Gush Etzion playing in the Ratisbonne Monastery courtyard, 1949. National Photo Collection of Israel, Photography Department, Goverment Press Office.

Talk to us about the community portrayed in Autumn Clouds (2014).

Autumn Clouds explores the post-traumatic condition through the eyes of a group of orphans and is set in an unknown place, a sort of mental space. A dramatic event has just occurred, but we don’t know what. There is no solution to the problem and everything is permeated by a strong sense of uncertainty. Presenting sacraments and rituals that are more guessed at than seen, the work investigates the meaning of faith in a world filled with tension, loss and violence, and it does so through long moments of “emptiness” that are intended to underline the lack of a choice.

Absence (2016) also shows us a community in a difficult situation of a dreamlike character.

Absence was made almost three years after Autumn Clouds. It portrays the journey of a group of refugees within a reality limited by social and religious constraints. In the imaginary ancient religion I have represented, called Mastane, there is a belief in patriarchal sanctification, so that the dead man becomes a saint. Using a language invented for the occasion, the video recounts an exhausting journey of return from the Holy Land, a journey that is longer and more difficult than expected.

A journey with no end?

A journey in search of what perhaps cannot be found. In all my works these communities seem very detached from what they are living through. All my characters represent a damaged state of being in a romantic setting. I am thinking of the pictures of the Romantic painters, in which very profound themes are set in landscapes of aching beauty.

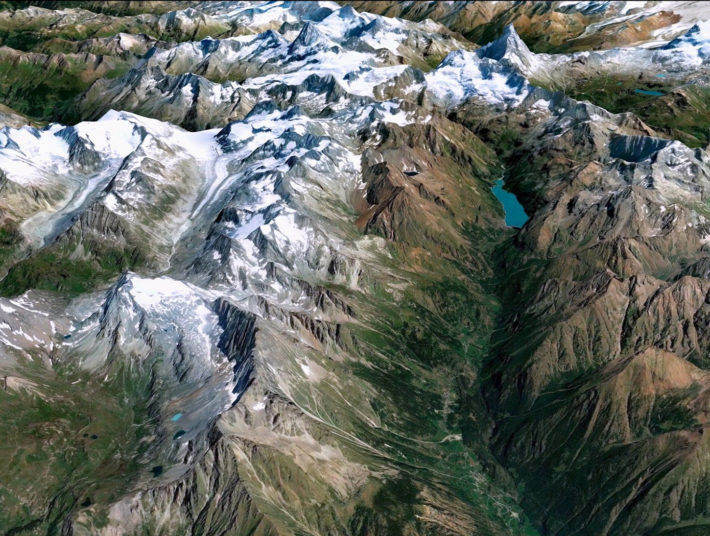

In Acreage (2018), a group of young people have to deal with a hostile and snowclad landscape: is this too the result of an unfortunate event?

Acreage is a three-channel installation that reflects on the various meanings of a piece of land that is only regarded as “territory.” A group of refugees find themselves in the mountains, in an unspecified place in which they have to stay for unknown reasons. In my works the posttraumatic moment often tends to be the consequence of a disaster. I grew up in a similar situation and I wanted to re-create the state of psychological tension that characterizes a violent territory. In all my works, there is a threat concealed behind the tranquil atmosphere. For me, the posttraumatic moment is essential. It is the representation of a catastrophe that has occurred, the moment in which everything has already happened and we find ourselves surrounded by the effects produced by an event, faced with a new reality. And in the face of all this, viewers are left to their own devices. They are given no clues to its interpretation.

Gili Lavy, Acreage, three-channel moving-image installation, still from video, 2017-18. Courtesy of Gili Lavy.

In Acreage, the landscape has a central role.

Yes, very much so. The feeling of emptiness, of bewilderment, is difficult to convey, but when I started to imagine Acreage, I immediately thought that a group of people in the Scottish Highlands would be able to put across the idea well. Shooting in that part of the world was a very powerful experience. I hadn’t planned to film the cold winds that blew on the set, but then I realized that they were a fundamental element. Nature played a very important part in the construction of the work. In Acreage, the human beings are like the wind: they arrive, pass by and tell us a great deal with their silence. In this work too I return to the concepts of absence and invisibility, and question the idea of the border, a constant cause of dispute and tension. I treated the land as an archive, leaving the viewer in front of a mysterious space, with no points of reference.

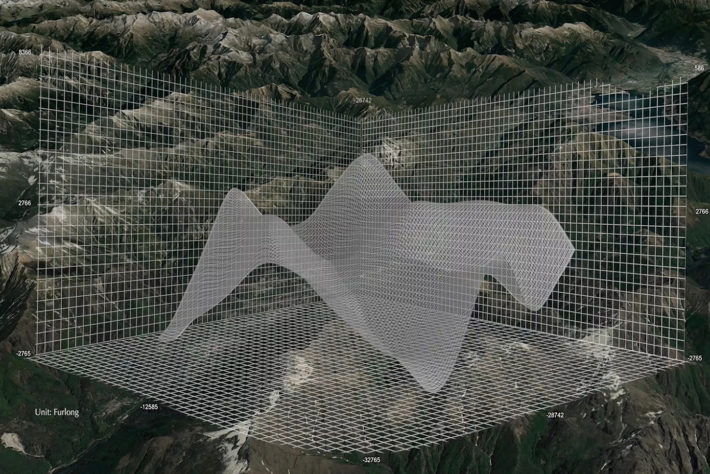

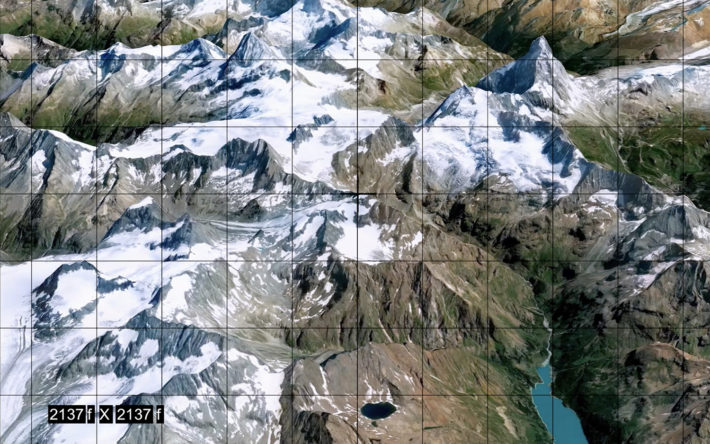

Furlong (2019), your most recent work, shown at the BAM in Palermo, presents a digital scan of the Earth’s surface. What do you mean by what you call the search for a terra nullius?

Terra nullius is a Latin expression that signifies “nobody’s land.” In international law it is used to describe an area that belongs to no one and that can be annexed by the first nation that discovers it, according to the logic of “finders keepers.” The furlong is a measure of distance that was used in the British empire. The work explores the act of measuring a piece of land, a strategic and mechanical operation that turns into a frantic search for an untouched, perhaps imaginary land. It is a journey in time and space in which we find that historical and political changes have left a mark on the geological structure of our planet. I have concentrated on images of lands in which the posttraumatic element is decisive, in order to reflect on geological catastrophes as well as political ones. The idea was to question the need to create borders between territories. Everything is entrusted to the setting: rural landscapes, primordial mountains and ancient places evoke a post-apocalyptic space that has no precise geopolitical coordinates. Furlong is an attempt to present land in its essence, isolated from any social and political phenomenon.

What are you working on now?

At the moment I am working on a major commission, a multichannel video installation that continues the inquiry into the need to create political borders, and does so by means of the tools used to map nature. Meanwhile, I continue to work with foundations and other bodies. I would very much like to work more closely with Italy.

Gili Lavy, Furlong, multichannel moving-image installation, 2019. Courtesy of Gili Lavy.

Gili Lavy, Furlong, multichannel moving-image installation, still from video, 2019. Courtesy of Gili Lavy.

Gili Lavy, Furlong, multichannel moving-image installation, still from video, 2019. Courtesy of Gili Lavy.

Gili Lavy, Furlong, multichannel moving-image installation, still from video, 2019. Courtesy of Gili Lavy.

Gili Lavy, Acreage, three-channel moving-image installation, still from video, 2018. Courtesy of Gili Lavy.

Gili Lavy, Acreage, three-channel moving-image installation, still from video, 2018. Courtesy of Gili Lavy.

Gili Lavy, Absence, single-channel moving-image installation, still from video, 2016. Courtesy of Gili Lavy.

Gili Lavy, Absence, single-channel moving-image installation, still from video, 2016. Courtesy of Gili Lavy.

Gili Lavy, Absence, single-channel moving-image installation, still from video, 2016. Courtesy of Gili Lavy.

Gili Lavy, Absence, single-channel moving-image installation, still from video, 2016. Courtesy of Gili Lavy.

Gili Lavy, Absence, single-channel moving-image installation, still from video, 2016. Courtesy of Gili Lavy.

Gili Lavy, Autumn Clouds, single-channel moving-image installation, still from video, 2014. Courtesy of Gili Lavy.

Gili Lavy, La mère divine, dual-channel moving-image installation, still from video, 2015. Courtesy of Gili Lavy.

Gili Lavy, La mère divine, dual-channel moving-image installation, 2015. Courtesy of Gili Lavy. Photo: Renato Ghiazza.

Gili Lavy, Absence, single-channel moving-image installation, 2016. Courtesy of Gili Lavy.