12 June 2019

Paolo Di Paolo, Italy’s Cartier-Bresson, ran the risk of being lost in the labyrinth of 20th-century history, just one more photographer among many, if it were not for the fact that twenty years ago his daughter Silvia, looking for a pair of skis in the cellar, came by chance across an immense archive of his pictures: 250,000 negatives, contact prints, prints and slides. A perfectly organized collection of material, dating from between 1954 and 1968. When his daughter asked him for an explanation of her discovery, he responded: “They’re mine, I took them. I used to be a photographer. I’ve put it all behind me now, I don’t want to talk about it.”1 Used to be indeed, because in 1966, when Mario Pannunzio’s magazine Il Mondo ceased publication, he took the decision to give up the profession of photographer (he would actually do so in 1968) and withdraw to the countryside, outside Rome, to study, write books and devote himself to his passions: winegrowing, his dogs, vintage cars. His life changed, but fortunately his talent has reemerged, thanks to that archive. Now in his nineties, he was born at Larino, in Molise, in 1925, Di Paolo is a shy, reserved and modest man, not at all how you would imagine a genius of 20th-century photography, a wizard of the humanist approach to the medium, of French derivation, and the creator of essential and powerful images. The man behind his rediscovery is Alessandro Michele: yes, the ebullient creative director who has succeeded in relaunching the Gucci brand in the space of just a few years, revolutionizing it. Passionate about photography and “fascinated by the contemporary look of the faces” and “the authentic style of his pictures, the intensity of life and experience they convey,”2 Michele decided that Gucci would be the sole sponsor of the splendid exhibition curated by Giovanna Calvenzi, Mondo Perduto, which will run at the MAXXI Museo nazionale delle arti del XXI secolo in Rome until September 1: the visitor is taken on an unprecedented journey back to the Italy of the fifties and sixties by over 250 pictures, divided up into various sections, whose subjects include protagonists from the world of art, the movies and culture as well as lots of ordinary people.

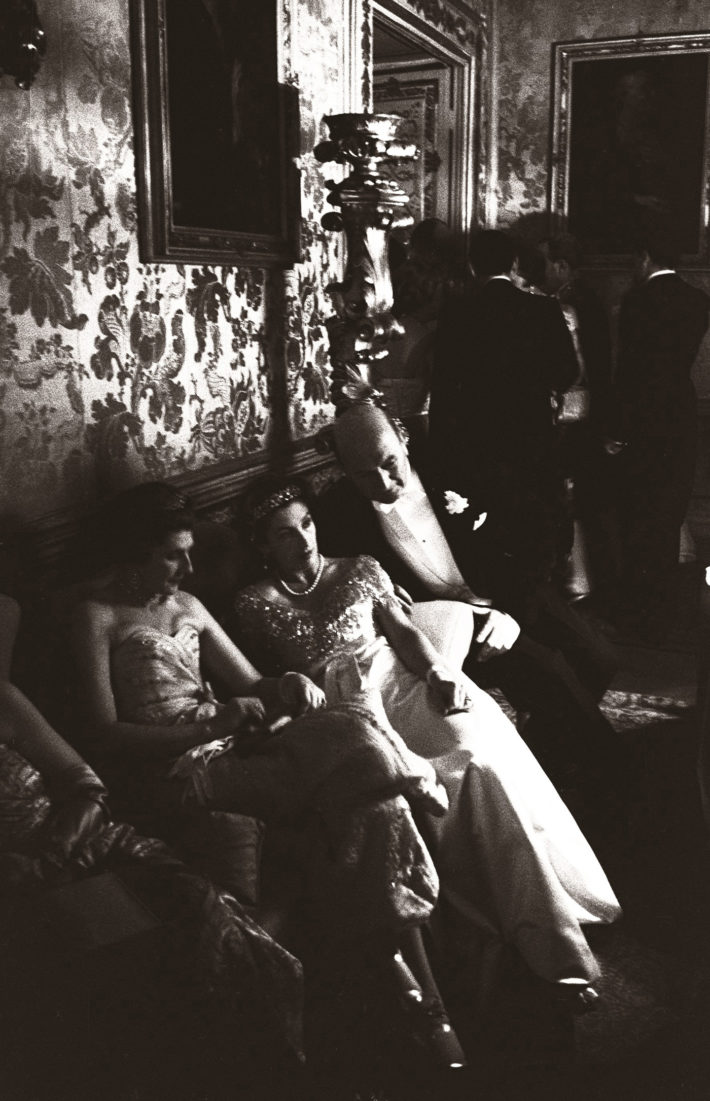

Ball at Palazzo Rospigliosi, Rome, 1958. Photo: Paolo Di Paolo, © Archivio Paolo Di Paolo, Courtesy MAXXI Photography Collection.

Paolo Di Paolo puts in an appearance with his calm voice and the cultured Italian of a former student of philosophy, speaking from the videos projected between the various sections of the exhibition. The first and stunning one is entitled Society/Rome and opens with a photo from 1954, I piccoli guerrieri di Monte Mario (The Little Warriors of Monte Mario). Three children shot from behind as they gaze at Rome, with the profile of the dome of St. Peter’s in the background, from the top of the Monte Mario hill, where the road called the Panoramica passes today. All of Di Paolo’s aesthetic is there: the immediacy, the discretion, the poetry entrusted to a stolen and yet true moment, with no staging. The same dimension can be found in a photo from 1962, taken for Il Mondo on the occasion of the opening of the Rome-Florence section of the Autostrada del Sole. The pictures in that feature did not go down well with the editorial staff of Il Mondo. Di Paolo, who was a candid and above all free spirit, produced a reportage that fifty years later still stirs us, but that at the time risked being too eccentric even for that eccentric journal in a format of 35 x 50 cm which practiced the art of illustration without captions, publishing emblematic photos, images that were a story in their own right, accompanying long and learned articles signed by the most influential intellectuals of the time but which the gossips claimed no one read. People bought Pannunzio’s Il Mondo, the story went, solely to leaf through it, to look at the pictures, to parade it as the status symbol of a cultivated, liberal, nonconformist élite, impervious to the Catholic-Communist grip of the big parties with mass-appeal. To bear witness to the opening of the new stretch of highway that was supposed to unite postwar rural Italy as it raced toward the economic boom, Di Paolo chose not to photograph the cutting of the ribbon, in the presence of a cardinal, mayors rigged out in the tricolor and a host of politicians, but to make his way along the same stretch of highway in advance, driving next to it on the Via Flaminia and the Via Tiberina and stopping on a little hill: he had decided to show the violent laceration inflicted by the freeway on the landscape of Tuscia. And he took the photo of two boys and an adult from behind, staring at the new road, one with a kitten on his shoulder next to a bunch of corncobs, another barefooted and lying on the ground in front of the fence around a field of cows, and finally a third, perhaps the father of the first two, holding a child in his arms and gazing at that endless stretch of road traversed by a single white car shooting past in the background.

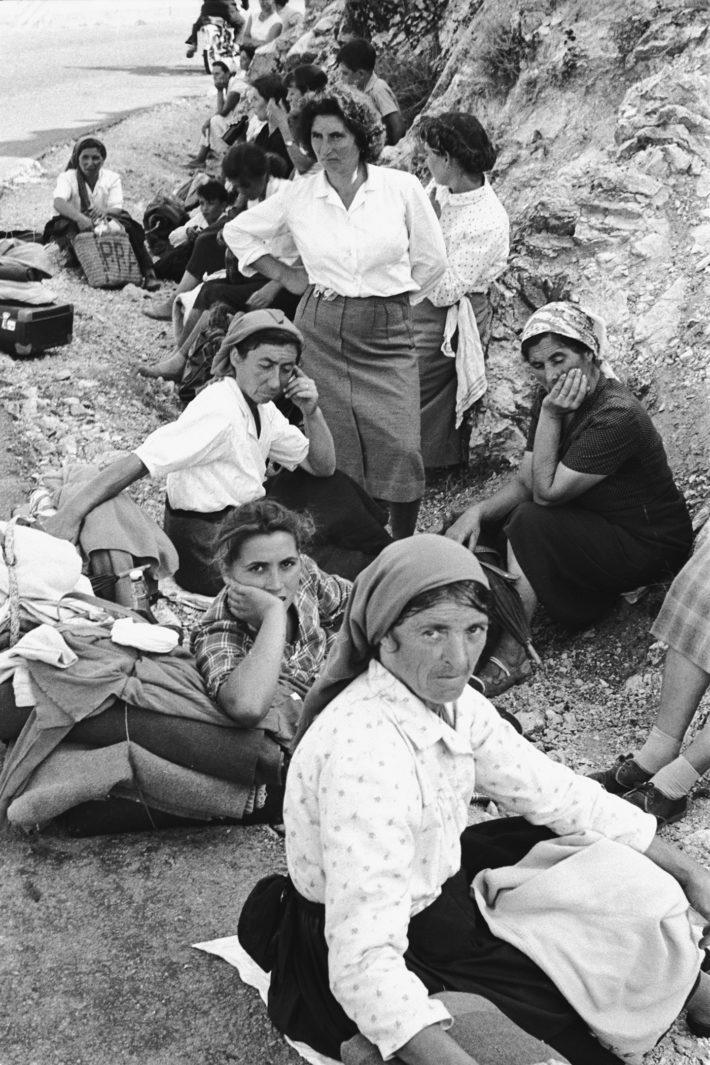

Pilgrims’ Rest, Passo delle Tre Croci between Molise and Campania, to the south of Cassino, 1957. Photo: Paolo Di Paolo, © Archivio Paolo Di Paolo.

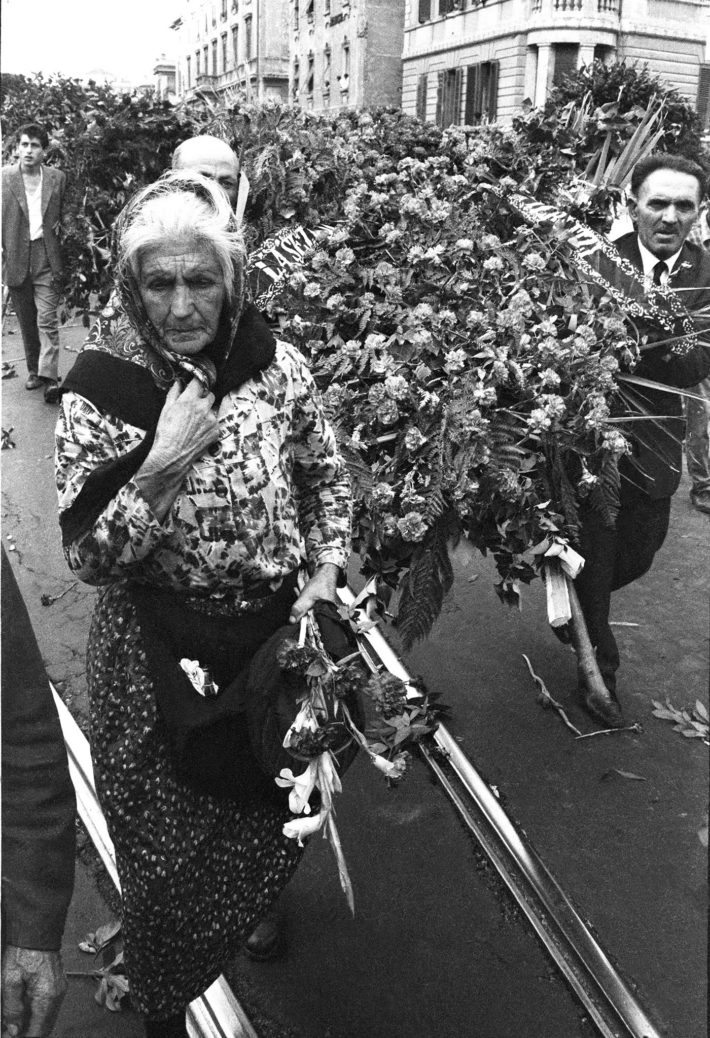

Then there are the pictures of the rural world, and here too there is no affectation, but an anthropological attention filled with empathy, sometimes brusque, often moved, always lucid, unwavering, flawless. Like the Sosta delle pellegrine (Pilgrims’ Rest) at the Passo delle Tre Croci between Molise and Campania, to the south of Cassino, a photo from 1957 taken in a part of the world with which Di Paolo, born in Larino, was thoroughly familiar. Some women, crouching in a row among the rocks of the mountain, their heads wrapped in scarves, stare into the lens with expressions filled with distrust, curiosity, amazement: no preciosity, no anthropological affectation, just a vivid attention to the harshness of existence. The same can be said of the elderly peasant woman who a few years later, in 1964, contritely follows the funeral procession of Palmiro Togliatti with a bunch of faded gladioli in her hand, and behind her a parade of garlands carried on mourners’ shoulders. If we think of the depravation of Neorealism, of the rhetoric of the humiliated and downtrodden, of the ideology of the party of the masses, here we are somewhere else, on a completely different plane: the scenes are sincere, vivid, sorrowful. The fact is that despite being a great photographer, Di Paolo always wanted to remain an amateur. And in fact at the entrance to the exhibition we find a quote from Emilio Cecchi, “The rose-tinted indulgence of his work is the exclusive heritage of the dilettante,” reminding us in ironic fashion that as a perfect amateur Di Paolo has always gone along with his instinct and kept his freedom: “The amateur always follows his instinct, he is a free person; the professional, on the other hand, works to commission, he has to do what is asked of him, and well. Above all he can’t say no,” he explained two years ago in conversation with Francesco Maria Orsolini3.

While studying at university in Rome, he lived for several years by his wits, before becoming the editor-in-chief of a travel magazine. One day he happened to see a Leica IIIc on display in a camera store at the Stazione Termini, fell in love with it, bought it on an installment plan, without even knowing how to use it, and quit his job. It was 1953, Di Paolo was almost thirty years old and started to take photographs for pleasure, frequenting the artists of the Forma 1 group who used to meet up at the Osteria Fratelli Menghi on Via Flaminia. One evening he showed some of his photos of the new Settebello, the train from Rome to Milan, to Rinaldo Ossola’s wife, and she offered to take them to Pannunzio’s Il Mondo. Some time passed, and then Di Paolo presented himself at the magazine’s editorial office, on the second floor of Via di Campo Marzio 24. It was the beginning of a collaboration that would last until March 13, 1966, when Di Paolo, having read the announcement of its closure in the journal’s editorial, went to the post office on Piazza San Silvestro to send the telegram that would put an end to his own career: “Today for me and for other friends the ambition to be a photographer has died.”4 Thirteen years and 573 photos published. For Di Paolo Il Mondo was an experience that left its mark, and it is no accident that in the exhibition it is brought back to life not just through his pictures, but also by an installation reproducing the furniture of the time, the editor’s desk under a print with a portrait of Cavour, the printer’s type on which Pannunzio measured the length of the articles with a piece of string and many illustrated pages of the magazine in display under glass.

The funeral of Palmiro Togliatti, Rome, August 25 1964. Photo: Paolo Di Paolo, © Archivio Paolo Di Paolo, Courtesy MAXXI Photography Collection.

These were the years of la dolce vita, when Rome and the studios of Cinecittà were besieged by producers, directors and actors from all over the world. Di Paolo lived through that time with great discretion. He was the epitome of the anti-paparazzo, ashamed even to be seen with a camera hung around his neck, and cultivated a singular approach that entailed a relationship of empathy, if not complicity, with the subject of his photograph. He displayed a sublime indifference to the idea of the scoop, and yet this did not prevent him from pulling several of them off. His first such scoop, the photo of the newly betrothed Lucia Bosè and Luis Dominguín on an outing to the Castelli, happened almost by chance, thanks to the friends with whom he frequented Otello alla Concordia, the restaurant on Via della Croce, a haunt of actors, directors and producers. Di Paolo, who was already contributing to La Settimana Incom, began to work with the magazine Tempo as well, proposing illustrated stories and doing features. He was known for being trustworthy, and so was able to gain access even to exclusive circles like those of the Roman aristocracy, which he observed with the same poetic disenchantment as when he depicted the world of people at the bottom of the heap. And so we have the photo of the ball at Palazzo Pallavicini Rospigliosi, in 1958, with two elegant and bored matrons slumped on a couch, and alongside a man making a rather awkward attempt to entertain them; and the surreal pictures of the wedding of Olimpia Torlonia in the basilica of Santi Apostoli, with butlers dressed in livery shot from behind under the portico and the hat of a guest in the foreground, echoing the circular shape of the apse.

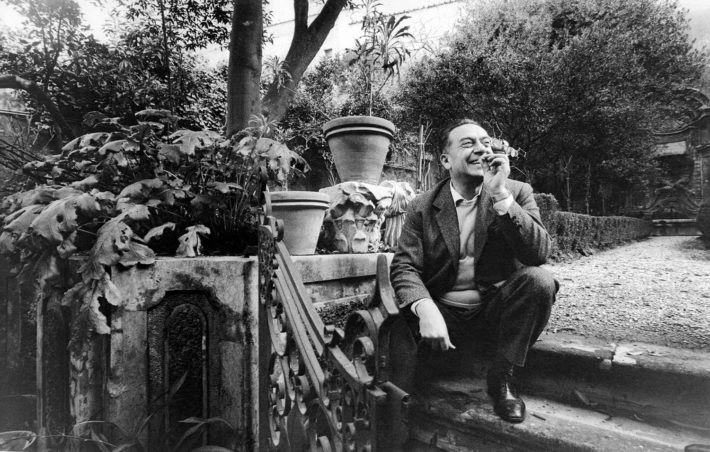

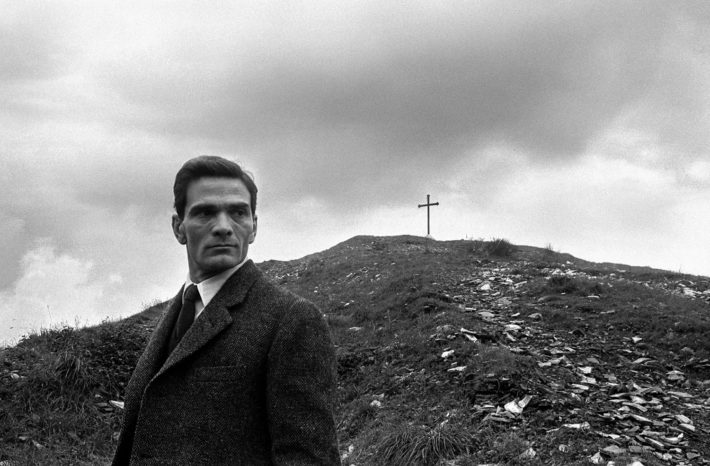

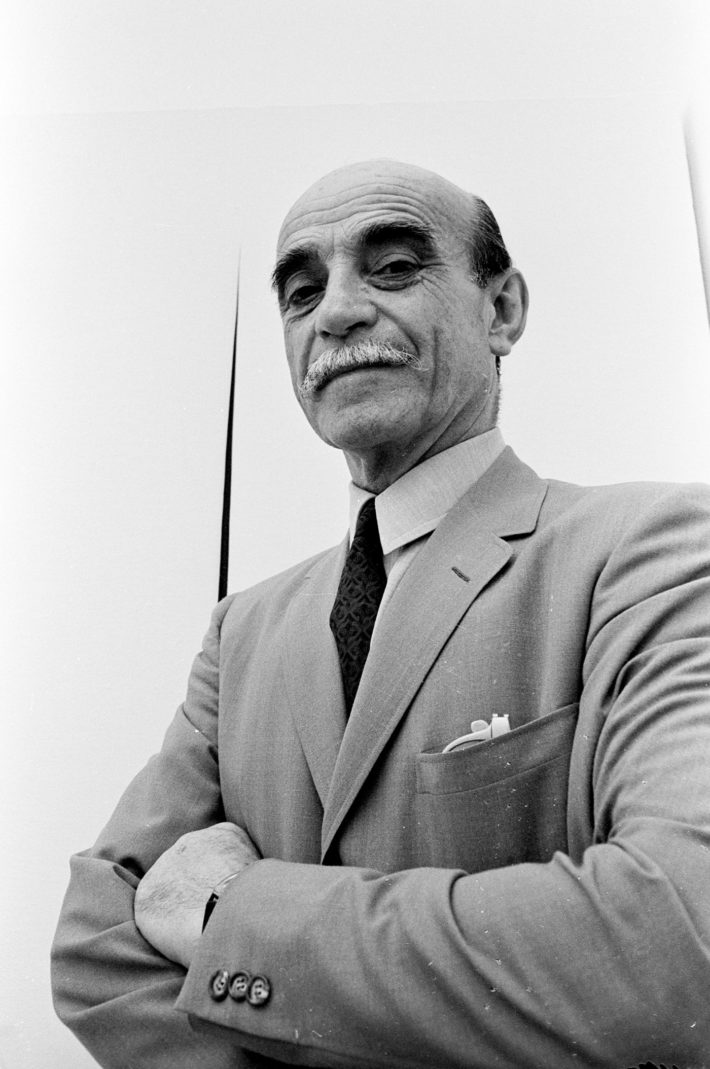

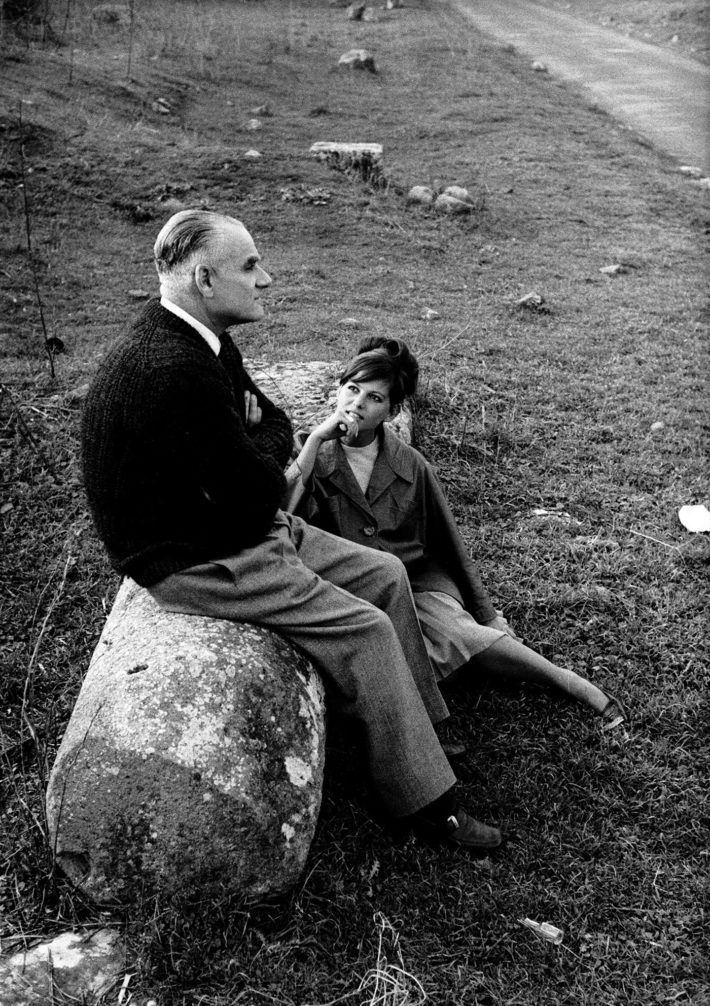

His finest photos came by chance, out of his acquaintance with actors, writers, artists and directors. Many remain unpublished, they were private affairs: Di Paolo is a discreet man, someone you can trust. There are photos of Mimmo Rotella doing one of his décollages in Piazza del Popolo, of Leoncillo Leonardi and Mario Mafai in their respective studios in Rome, of Enrico Castellani in front of his sculptures in relief, of Lucio Fontana, looking very elegant in jacket and necktie, in front of his “slashes.” Dressed in a tight-fitting bodice that left her shoulders bare, the legendary director of the Galleria Nazionale di Arte Moderna, Palma Bucarelli, smiles next to a thoughtful Giorgio Bassani, in the nymphaeum of Valle Giulia, at the Premio Strega of 1957, while Elsa Morante chats with Maria Bellonci. For the weekly Tempo, at the suggestion of Sennuccio Benelli, Paolo Di Paolo staged some “impossible encounters,” coupling the poet Salvatore Quasimodo and Fellini’s star Anita Ekberg, the singer Mina and Luchino Visconti, the aristocratic director of Senso. Or the communist Nilde Iotti and the cabaret artiste Renato Rascel, the writer Alberto Moravia and Claudia Cardinale: he seated on a fallen column and she on the ground, gazing up at him. Sometimes he plays on the strong contrast between black and white, like the one between the raven chignon of Gina Lollobrigida and her diaphanous skin, in the foreground, and the sculpted white hair above the Grecian and sunburned features of Giorgio de Chirico. For Giovanni Ansaldo and Jayne Mansfield, the contrast is instead between discordant frames: massive and almost immobile that of the famous Genoese journalist, a friend of Ciano’s, wearing a hat and with a walking stick behind his back, slender and sinuous that of the American film star, an erotic bombshell in high heels, dressed in a satin pantsuit. Then there are the portraits of artists and writers always caught unawares, without artifice, like Renato Guttuso smiling as he smokes a cigarette seated on the steps of a garden or Ezra Pound, hieratic between the bare walls of his monastic studio; Carlo Emilio Gadda in front of the little elephant of Santa Maria della Minerva and Ungaretti playing with his cat against the backdrop of shelves piled with books.

Charlotte Rampling on the set of Sequestro di persona, Sardinia, 1966. Photo: Paolo Di Paolo, © Archivio Paolo Di Paolo.

With actors the pace changes, but is always intimate, sincere. Paolo Di Paolo observes conspiratorially the budding love affair between Yves Montand and Simone Signoret, following them like an ordinary tourist around the Roman Forum on a rainy day. Here we see the pair kissing like teenagers under the walls of the Palatine Hill; Yves Montand with his cheeky face aping a statue, his umbrella held high and one leg raised, while Simone gazes raptly at her new Adonis. Both of them are as free and easy as in real life, since they know that those pictures will never end up in the newspapers. Empathy, complicity and discretion open every door. One day, Egle Monti suggested he go to see Anna Magnani at her villa at Punta Rossa, on Cape Circeo. After lunch in an atmosphere of suspicion, Magnani changed into a bathing costume and invited him to go down to the beach with her to photograph Luca, the disabled son she had always kept secret. They are photos of a disarming humanity. Very different from those of Charlotte Rampling, who instead summoned Di Paolo to photograph her almost nude on the set of Sequestro di persona (Sardinia Kidnapped), seated in an armchair wearing nothing but pantyhose and a goatskin. Then there was the meeting with Pier Paolo Pasolini, which happened in 1959 when Di Paolo proposed doing a feature on the vacations of the Italians to Arturo Tofanelli, editor of the periodicals Tempo and Successo. Tofanelli liked the idea, but wanted the texts to be written by Pasolini, thirty-seven at the time and already the author of Ragazzi di vita and Una vita violenta. The pair set off together from Rome for Ventimiglia, the first stop on their journey, in Di Paolo’s MG TD Arnolt, but soon realized they had different aims and sensibilities: “He was looking for a lost world of literary phantoms, an Italy that was no longer there, I was seeking an Italy that looked to the future,” Di Paolo would say.5 So they decided to tackle the subsequent stages of the journey separately. The reportage, entitled “La lunga strada di sabbia,” would be published in three installments in Successo, with a selection of Di Paolo’s pictures that fixed forever the identity of a country undergoing change and looking forward. Emblematic, in this sense, the photo of the family made up two adults, perhaps grandparents, wrapped up in their clothing, and a child in swimming trunks and singlet: they are on the shore, the sea in front of them, staring into the distance. It is a melancholic image that speaks of our illusions, our hopes, of the bitter-sweet romance that is part of the story of every Italian family.

Paolo Di Paolo. Mondo Perduto

Curated by Giovanna Calvenzi

MAXXI Museo nazionale delle arti del XXI secolo, Rome

April 17–September 1, 2019

Between Rimini and Bellaria, photo from the reportage “La lunga strada di sabbia,” 1959. Photo: Paolo Di Paolo, © Archivio Paolo Di Paolo, Courtesy MAXXI Photography Collection.

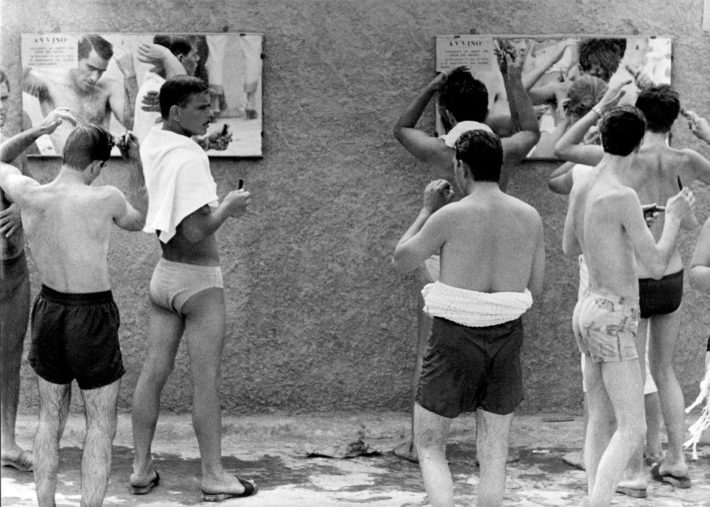

Lido di Corollo, Naples, 1959. Photo: Paolo Di Paolo, © Archivio Paolo Di Paolo.

Viareggio, 1959. Photo: Paolo Di Paolo, © Archivio Paolo Di Paolo.

Sofia Loren sul set di “Sofia Loren on the set of Pane, amore e…, Pozzuoli, Naples, 1955. Photo: Paolo Di Paolo, © Archivio Paolo Di Paolo.

Maria Bellonci, with the fan, Elsa Morante, Giorgio Bassani, Palma Bucarelli and Paolo Monelli at the Premio Strega, Rome, 1957. Photo: Paolo Di Paolo, © Archivio Paolo Di Paolo.

Renato Guttuso at Salita del Grillo, Rome, 1964. Photo: Paolo Di Paolo, © Archivio Paolo Di Paolo.

Autostrada del Sole, opening of the Rome-Florence section, 1962. Photo: Paolo Di Paolo, © Archivio Paolo Di Paolo.

Pier Paolo Pasolini at the “Monte dei Cocci,” Rome, 1960. Photo: Paolo Di Paolo, © Archivio Paolo Di Paolo, Courtesy MAXXI Photography Collection.

Pier Paolo Pasolini at the “Monte dei Cocci,” Rome, 1960. Photo: Paolo Di Paolo, © Archivio Paolo Di Paolo, Courtesy MAXXI Photography Collection.

Underpass, New York, 1963. Photo: Paolo Di Paolo, © Archivio Paolo Di Paolo, Courtesy MAXXI Photography Collection.

Gina Lollobrigida and Giorgio de Chirico, Rome, 1961. Photo: Paolo Di Paolo, © Archivio Paolo Di Paolo, Courtesy MAXXI Photography Collection.

The Little Warriors of Monte Mario, Rome, 1954. Photo: Paolo Di Paolo, © Archivio Paolo Di Paolo.

Lucio Fontana at the Venice Biennale, 1966. Photo: Paolo Di Paolo, © Archivio Paolo Di Paolo.

Simone Signoret and Yves Montand, Aventino, Rome, 1956. Photo: Paolo Di Paolo, © Archivio Paolo Di Paolo.

Giovanni Ansaldo and Jayne Mansfield, from the series “Gli incontri impossibili” published in Tempo, 1961-62. Photo: Paolo Di Paolo, © Archivio Paolo Di Paolo.

Alberto Moravia and Claudia Cardinale, from the series “Gli incontri impossibili” published in Tempo, 1961-62. Photo: Paolo Di Paolo, © Archivio Paolo Di Paolo.

Monica Vitti and Michelangelo Antonioni, Rome, 1958. Photo: Paolo Di Paolo, © Archivio Paolo Di Paolo.

Wedding of Olimpia Torlonia, Rome, 1965. Photo: Paolo Di Paolo, © Archivio Paolo Di Paolo.

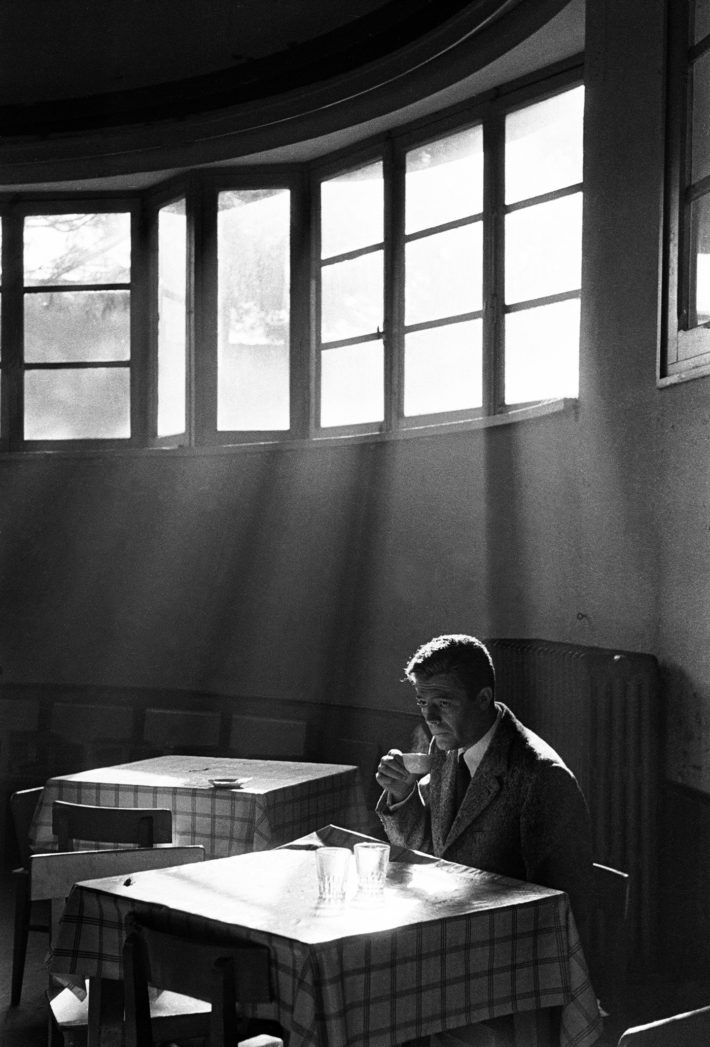

Marcello Mastroianni, undated. Photo: Paolo Di Paolo, © Archivio Paolo Di Paolo, Courtesy MAXXI Photography Collection.

Oriana Fallaci, Film Festival, Venice Lido, 1963. Photo: Paolo Di Paolo, © Archivio Paolo Di Paolo.

Fashion photo, Tor di Nona, Rome, 1957-58. Photo: Paolo Di Paolo, © Archivio Paolo Di Paolo.

Stroll on Via Monte Napoleone, Milan, 1962. Photo: Paolo Di Paolo, © Archivio Paolo Di Paolo.

Notes

1 Silvia Di Paolo, “Mio padre,” in Paolo Di Paolo. Fotografie 1954-1968, ed. Giovanna Calvenzi with the collaboration of Silvia Di Paolo, catalogue of the exhibition Paolo Di Paolo. Mondo Perduto at the MAXXI, Rome (Venice: Marsilio, 2018), 11.

2 Alessandro Michele, “Le emozioni nel racconto di Paolo Di Paolo,” in Paolo Di Paolo. Fotografie 1954-1968, 9.

3 “Vi racconto che cos’era Il Mondo di Pannunzio, dove diventai fotografo,” interview with Paolo Di Paolo conducted by Francesco Maria Orsolini, Il Reportage, no. 30 (April-June 2017).

4 Quoted in Giovanna Calvenzi, “Un mondo perduto o un mondo ritrovato?” in Paolo Di Paolo. Fotografie 1954-1968, 291.

5 Ivi, 290.