19 September 2019

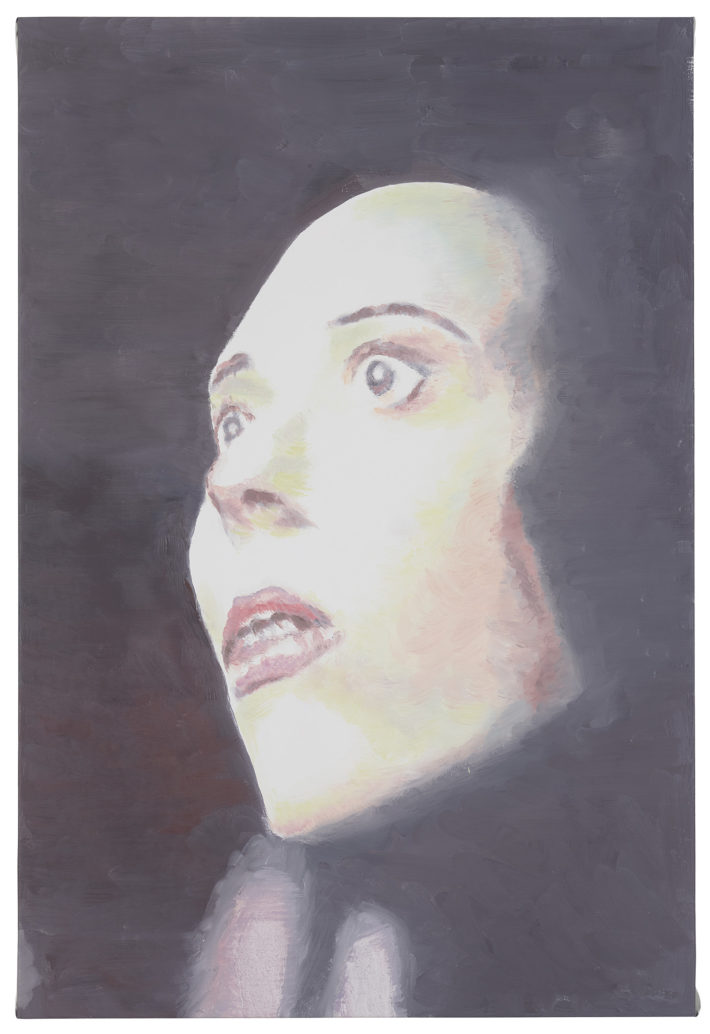

A piece of advice for anyone wishing to visit Luc Tuymans’s major exhibition at Palazzo Grassi: get hold of the indispensable guide edited by Marc Donnadieu (you can download it from the website). Read it all and thoroughly. Otherwise you will run the risk of coming out of the exhibition without having experienced its most intense moments. This is not my opinion, it is Tuymans himself who makes the suggestion: “The small gap between the explanation of a picture and a picture itself provides the only possible perspective on painting.”1 To put it another way: what you will see represented on the canvases of the painter from Antwerp will not be comprehensible if you are unaware of the motivations that induced the artist to choose that subject. For instance: when you stand in front of the portrait of a man in a pith helmet, there is nothing in the picture to tell you that it is an image of Issei Sagawa—as its title declares. And without knowing that its subject is the Japanese man who, in 1981, killed and cannibalized a fellow student at the Sorbonne in Paris, you will not in any way be able to grasp, in all its eloquent ambiguity, the poetry of that image. It is clear that the artist’s style, formal choices and undeniable technical skill are essential for the game to function, otherwise it would be sufficient to read the explanations, without even going to the exhibition. So: one eye on the pictures, one eye on the guide. End of the advice. In reality, when you come to think of it, this is not so much a recommendation as the key to the interpretation of a line of artistic research that derives its fascination precisely from the aura of mystery in which it is cloaked. An aura that Caroline Bourgeois, curator of the exhibition, defines as “his silence,” explaining that Tuymans “doesn’t take viewers by the hand but on the contrary gives them the freedom to decide what the painting’s real subject is, what is said, and what is suggested off frame.”2

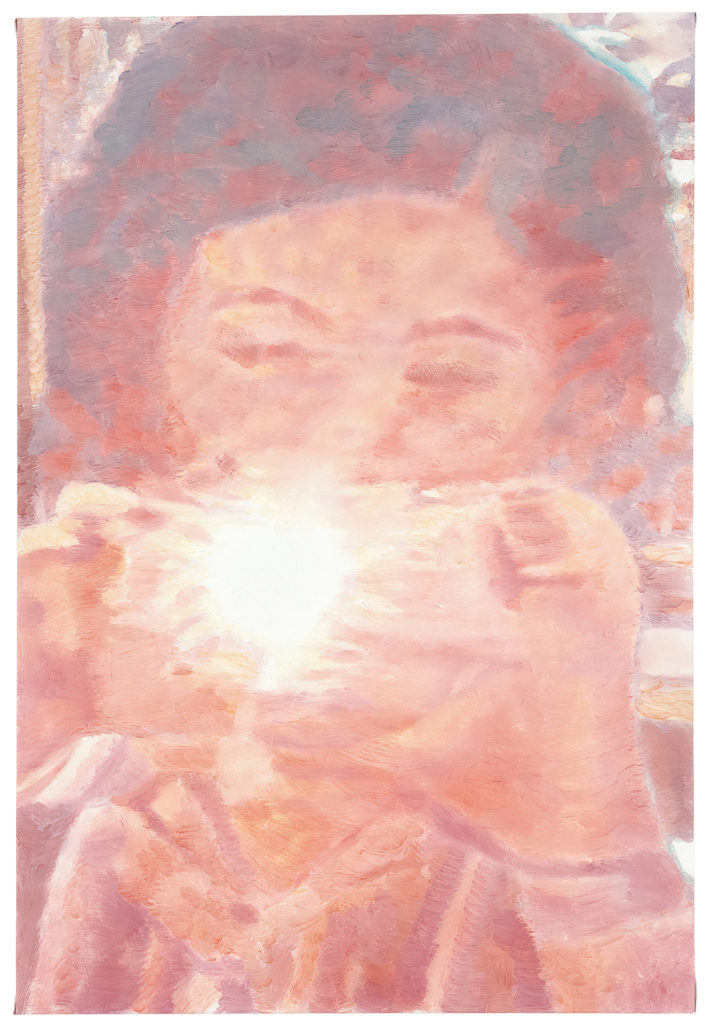

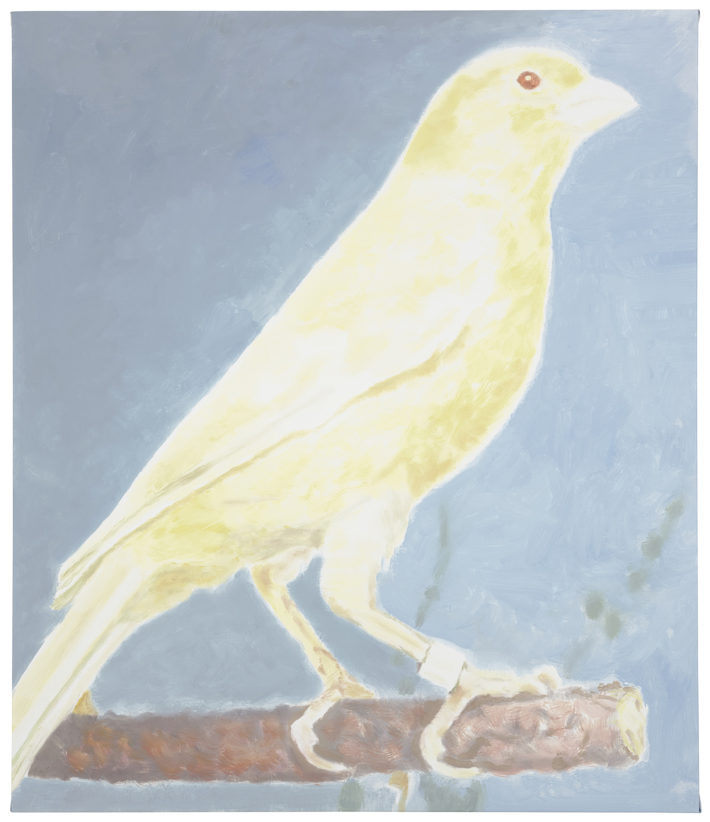

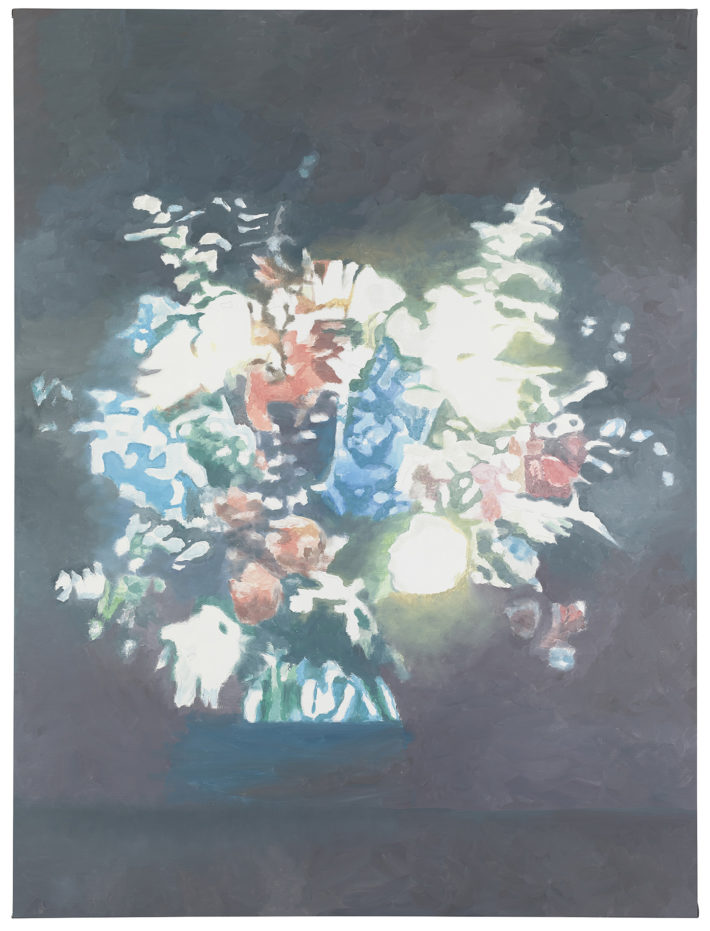

Luc Tuymans, Candle, 2017, oil on canvas, private collection. Courtesy and photo: Studio Luc Tuymans, Antwerp.

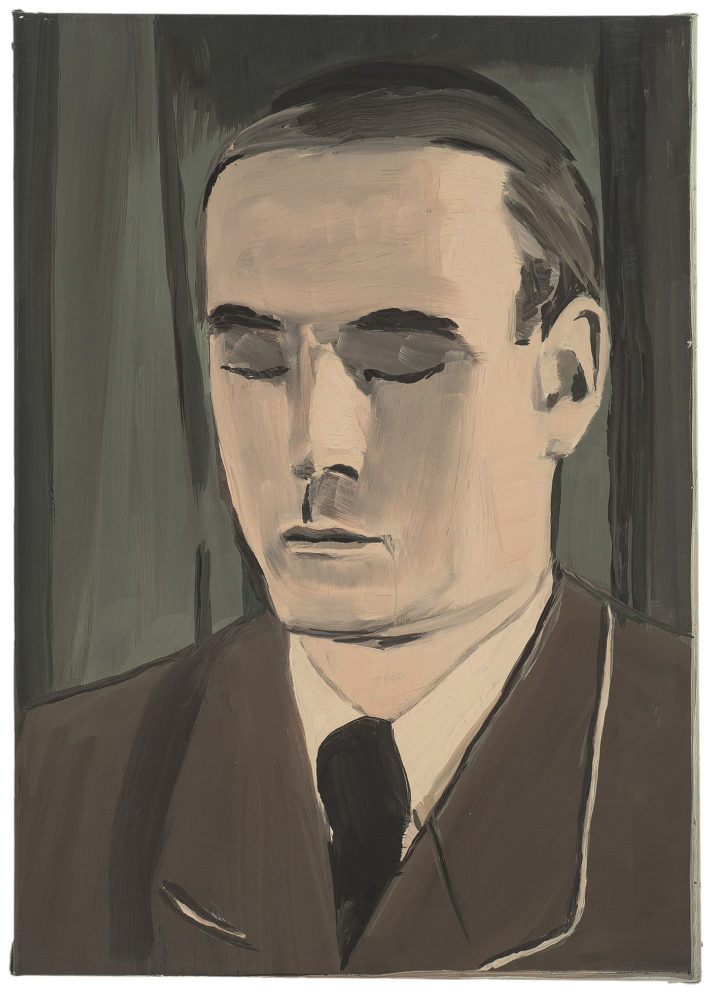

And so, left to our own devices but equipped with the guide in A5 format, we visitors make our way with courage and curiosity into the brightly lit inner courtyard of Palazzo Grassi. Here the painter has had a large mosaic made out of marble. Taking up the whole of the floor, it has the same title and motif as a work from 1986: Schwarzheide. The image is that of a row of trees viewed from below, standing out against a white sky. The work is traversed by eight vertical lines that divide it into nine strips. Donnadieu explains that Schwarzheide is the name of one of the forced labor (not death) camps in the Germany of the Third Reich. The subject is based on a drawing by one of the prisoners, Alfred Kantor, who had cut it into strips to avoid it being confiscated. The work can be walked on. After crossing it, we come to the grand staircase, above which is set a small painting: Secrets (1990). It is a portrait with his eyes closed of Albert Speer, chief architect of the Nazi party and Minister of Armaments and War Production of the Third Reich. The portrait is tightly framed, passport photo style. He is facing Schwarzheide, but does not see it. In his two books, Inside the Third Reich and Spandau, the Secret Diaries, Speer claimed not to have been aware of the final solution for the Jews ordered by Hitler. It is an opening worthy of his reputation as an engaged artist, one who tackles sensitive themes such as the Holocaust, colonialism and the dark sides of religion or contemporary politics. His own life has been marked by the contradictions of history: his mother’s family had played a part in the Dutch Resistance and hidden refugees, while two of his father’s brothers had been members of the Hitler Youth. One of them, moreover, was called Luc, like Tuymans.

Luc Tuymans, Instant, 2009, oil on canvas, private collection. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London. Photo: Studio Luc Tuymans, Antwerp.

The theme of Nazism crops up several times in the exhibition, which presents 80 works produced over the entire course of his career. In Our New Quarters (1986) the artist reproduces the design of one of the postcards that detainees at Theresienstadt, a “model” transit camp set up by the Nazis to mislead foreign media about the reality of the concentration and death camps, were invited to send to their loved ones. In the triptych Recherches (Investigations, 1989), the painter uses photographs he took at the concentration camps of Auschwitz and Buchenwald: a lamp on the desk of a Nazi officer, the tooth of a prisoner and the view from the window of an office. In Toter Gang (Dead End, 2018), he uses the image of the steel door that led into Hitler’s bunker at Berchtesgaden. These are reflections on the regime’s propaganda, on its profanation of corpses and on absolute evil. They are almost notes, painted with a calculated haste that is a hallmark of his style (every picture, however large or small, was finished in the course of a single day). The horror is never tackled head on, the abyss is always concealed behind the banality of ordinary objects or everyday situations.

Luc Tuymans, Toter Gang, 2018, oil on canvas, private collection. Courtesy Luc Tuymans and David Zwirner, New York/London. Photo: Studio Luc Tuymans, Antwerp.

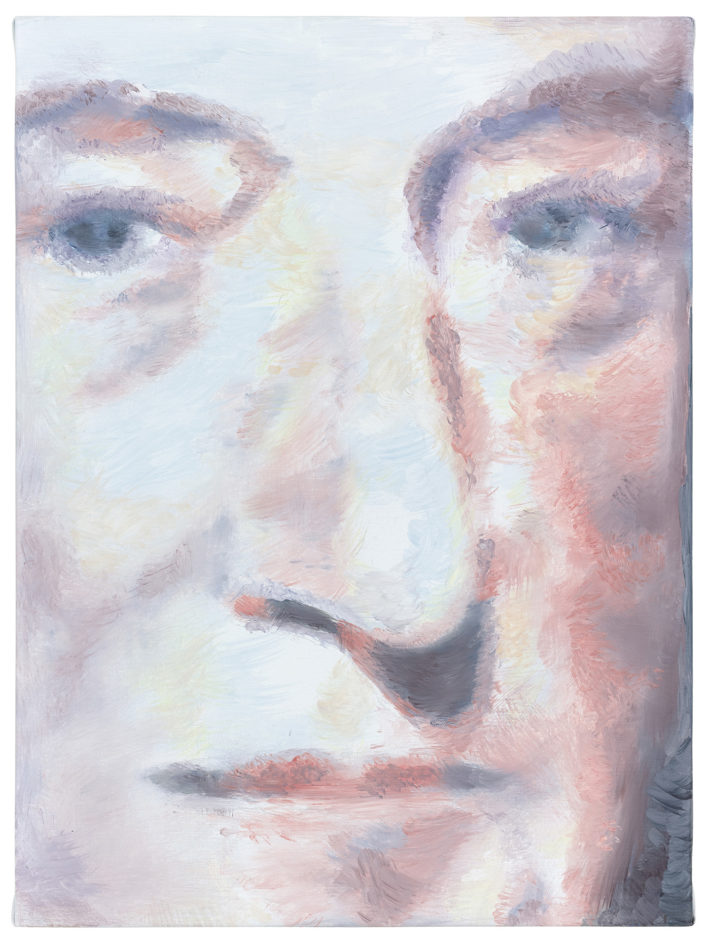

Tuymans’s take on the theme of September 11 is surprising too. The occasion was that of Documenta 11 at Kassel, in 2002, where just a few months after the attacks in New York it was expected that the artists would try to deal with the subject. “My wife and I were there during 9/11. We saw the planes going into the buildings from our hotel room. I thought it was impossible to do something with the event at that time. It’s not the way that painting works,” the artist has explained.3 So he chose to create Still Life (2002), whose dimensions of 3 by 5 meters probably make it one of the biggest such paintings in the history of art. A delicate composition of fruit alongside a jug of water floats in a neutral space, where the surface on which the objects are set can be imagined thanks to the diminutive shadow they cast. Donnadieu writes: “The point is not to show the explosion, the two smashed buildings, or the bodies buried under the rubble, but what is left beyond good and bad, after the catastrophe, once the cloud of dust has settled: the natural or human determination to keep going no matter what, to grow again, to rethink oneself, fruits and water, substance and color, the density of life being reborn. Still life can also mean that there is, still, life.”4 In Venice the large picture hangs next to the small canvas William Robertson (2014), a portrait of the 18th-century Scottish historian and theologian, again depicted in a close-up of the face that makes the intense blue of the eyes stand out. It is as if, to look at Still Life, Tuymans has asked to borrow the penetrating gaze of the Enlightenment intellectual.

Luc Tuymans, William Robertson, 2014, oil on canvas, The Broad Art Foundation. Photo: Studio Luc Tuymans, Antwerp.

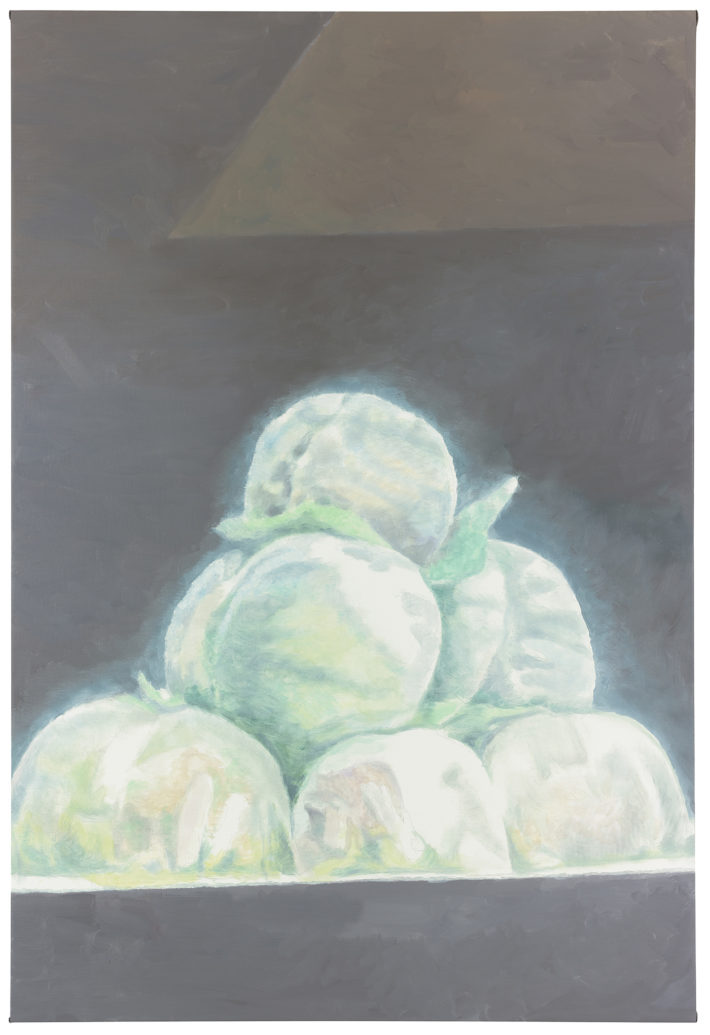

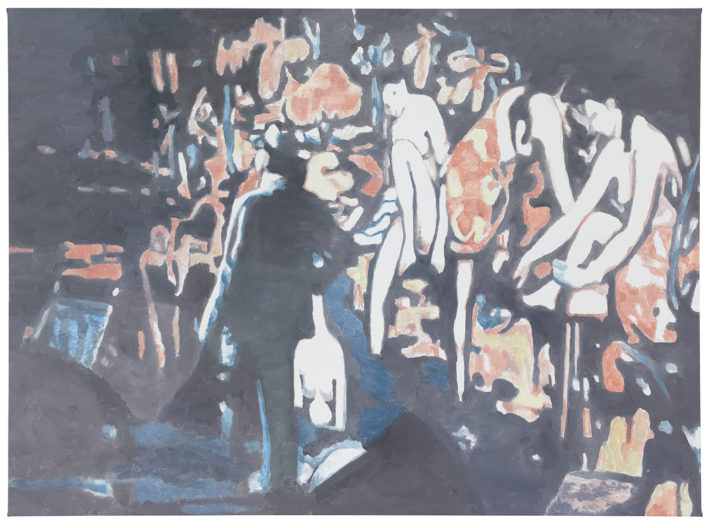

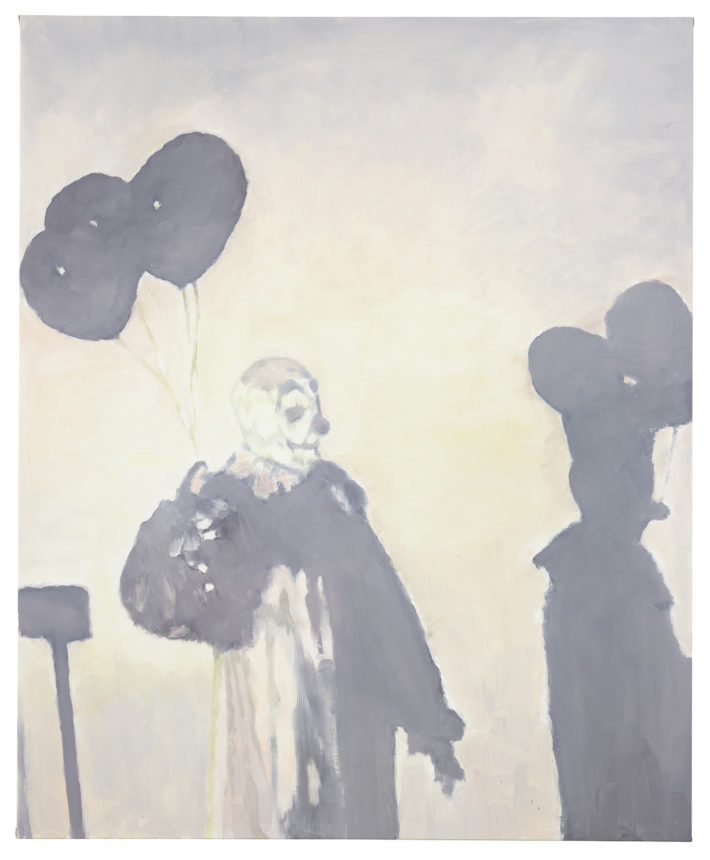

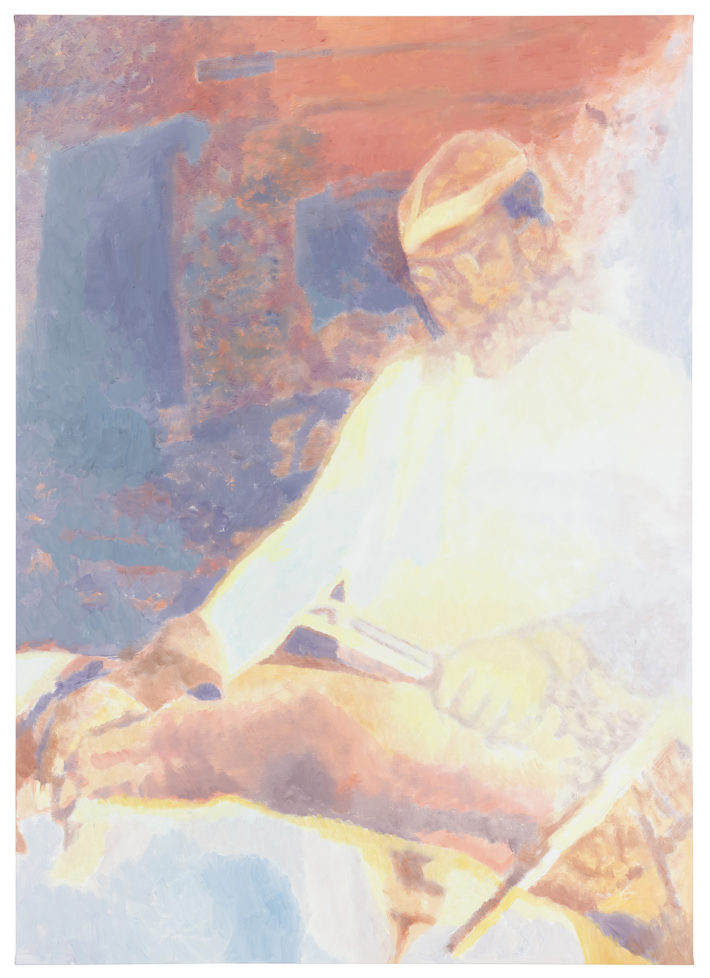

The oblique approach taken by Tuymans, who seems to derive a certain amount of pleasure from making the viewer feel uneasy, is exemplified by Murky Water (2015), an extraordinary triptych commissioned by the Dutch municpality of Ridderkerk, which wanted a tapestry for its town hall. The artist chose a subject very different from what a local authority would have thought suitable for celebrating the beauties of its town: three views, based on the same number of polaroid pictures, of Ridderkerk’s murky canals. Algae and drinking straws floating on their putrid and stagnant waters. It is no surprise that today the work no longer belongs to the municipality which commissioned it, but to the Collezione Prada. And yet the three canvases emanate a strange sort of splendor, vibrant with a light that is at once pale and clear. The murky water, a reflection of personal and collective corruption, seems to have been transfigured. It is the same light as in Sundown (2009) or Instant (2009), and above all as in Candle (2017), where nothing is left of the candle but its name and it is the whole painting that turns into light. In recent years Tuymans has perfected his technique of painting, turning it more and more into a refined investigation of the potentialities of gradations of color. The painter, explains Jarrett Earnest, “builds his pictures with very finely calibrated color dynamics—a wide range of hues in every work, though kept within a narrow tonal range. A sun-bleached palette of porcelain, cream, and bone somehow manages to infuse rosy pinks, buttery yellows, and deep lavenders.”5 It is only when you look closely at the canvases that you can discern this play of liquid and rapid brushstrokes, which creates—viewed from a distance—a luminous and magical aura. It is an effect that can also be found in pictures of subjects not directly connected with light. I’m thinking of Peaches (2012), Cook (2013) Ballone (Balloons, 2017) and even the aforementioned Toter Gang.

Luc Tuymans, Peaches, 2012, oil on canvas, private collection. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London. Photo: Studio Luc Tuymans, Antwerp.

Arriving at the end of the exhibition, we walk back through it again, partly to be sure of not having missed anything and partly in order to reconsider it in the light of the title that Tuymans himself chose for his show in Venice: La Pelle (The Skin). It is an allusion to the novel of the same name by Curzio Malaparte, which speaks of Naples liberated from the Germans and, at the same time, invaded by Allied troops in 1943, at the height of the Second World War. At Palazzo Grassi, the only reference to the writer is in reality a citation of Jean-Luc Godard’s film Le Mépris (Contempt, 1963), based on a novel by Alberto Moravia and shot on Capri in the splendid Villa Malaparte where La pelle was written. If it were not for the subject Tuymans’s picture would not attract much attention, but it says a great deal about the artist’s way of thinking and working. The picture represents the villa’s fireplace, behind which is concealed a small window that, but this is something only we who have read the catalogue know, faces onto the sea of Capri. The painting lives off the reflected light of the myths to which it makes reference: Godard, the Nouvelle Vague, Brigitte Bardot, Michel Piccoli, the fascination of the villa itself. But it also evokes the dimension of a humanity corrupted by the events of life, as happens in the relationship between the protagonists of Le Mépris and in the war-torn Naples described in La pelle. We think about these things walking back through the rooms of Palazzo Grassi, asking ourselves where, hanging on these walls, depicted in oil on canvas, this corruption really appears. Hanging it is, but it can’t be seen. It takes shape in our heads only at the moment in which the cognitive trap set by Tuymans is sprung. When, that is, we become aware of the rift between what we see and what we know about the work; or more precisely, when we realize that what is painted is never the direct representation of something that exists in reality, but the translation into painting of an initial image that, for its part, had already distanced itself from the world, in the ambiguous manner of which only images are capable: showing solely what they want to show.

Luc Tuymans, München, 2012, oil on canvas, Pinault Collection. Photo: Studio Luc Tuymans, Antwerp.

Tuymans says: “I’m a contemporary artist, which means that I work with images. There’s nothing unusual in that. By contrast, the choice that one makes is extraordinary, because it’s not really immediate. To my mind, it’s important to discover the meaning of things. If I see an image, I need to know where it comes from, what it might mean. Or it might be that I don’t understand it, and that’s why it attracts me.”6 Elsewhere he adds: “I don’t believe that all images are real. I’m wary of them, and of my own images too. We should always mistrust, ask ourselves questions.”7 And in yet another place he declares: “I can only observe that behind the mask of what is presented as ‘image’ lies a substantial loss of meaning.”8 We need to understand better what Tuymans intends by the word “meaning.” Perhaps something that needs to be sought through images and that images help us to mislay. Emerging from Palazzo Grassi one has a feeling of vertigo. Before getting back on board the vaporetto, a sort of awareness surfaces in us: we have understood that we haven’t understood. A rather old and somewhat Socratic feeling. Which, luckily, has not stripped us of our desire to go back and look again. At the painting and the world.

Luc Tuymans: La Pelle

Curated by Caroline Bourgeois and Luc Tuymans

Palazzo Grassi, Venice

March 24, 2019-January 6, 2020

Luc Tuymans, Schwarzheide, 2019, marble mosaic, after the 1986 oil on canvas of the same name, Fantini Mosaici, Milan. Installation view, La Pelle, Palazzo Grassi, Venice, 2019. Photo: Matteo De Fina, Palazzo Grassi.

Luc Tuymans, Our New Quarters, 1986, oil on canvas, MMK Museum für Moderne Kunst Frankfurt am Main. Gift of the artist. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London. Photo: Ben Blackwell.

Luc Tuymans, Sundown, 2009, oil on canvas, private collection. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London. Photo: Studio Luc Tuymans, Antwerp.

Luc Tuymans, Le Mépris, 2015, based on a photograph by François Halard, Mimi Haas Collection. Photo: Studio Luc Tuymans, Antwerp.

Luc Tuymans, Issei Sagawa, 2014, oil on canvas, Tate. Purchased with the funds provided by Tate Members, Tate International Council, the Nicholas Themans Trust and Art Fund, 2017. Photo: Studio Luc Tuymans, Antwerp.

Luc Tuymans, Magic, 2007, oil on canvas, private collection, Brussels. Photo: Studio Luc Tuymans, Antwerp.

Luc Tuymans, Allo! I, 2012, oil on canvas, private collection. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London. Photo: Studio Luc Tuymans, Antwerp.

Luc Tuymans, Isabel, 2015, oil on canvas, private collection. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London. Photo: Studio Luc Tuymans, Antwerp.

Luc Tuymans, Ballone, 2017, oil on canvas, private collection. Photo: Studio Luc Tuymans, Antwerp.

Luc Tuymans, Cook, 2013, oil on canvas, private collection. Photo: Studio Luc Tuymans, Antwerp.

Luc Tuymans, Technicolor, 2012, oil on canvas, private collection. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London. Photo: Studio Luc Tuymans, Antwerp.

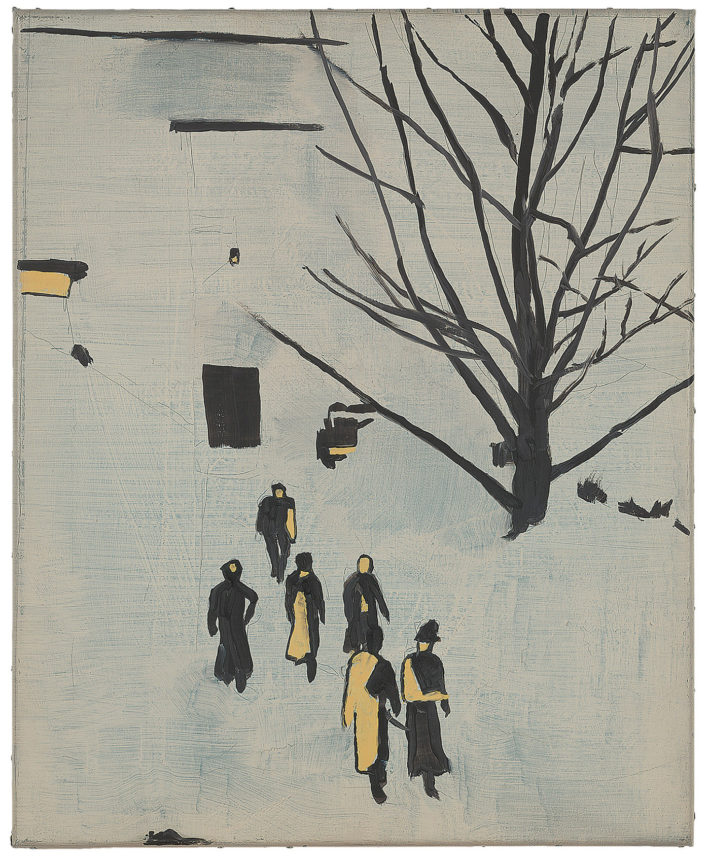

Luc Tuymans, Wandeling, 1989, oil on canvas, private collection. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London. Photo: Ben Blackwell.

Luc Tuymans, Secrets, 1990, oil on canvas, private collection. Courtesy Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp. Photo: Paul Hester.

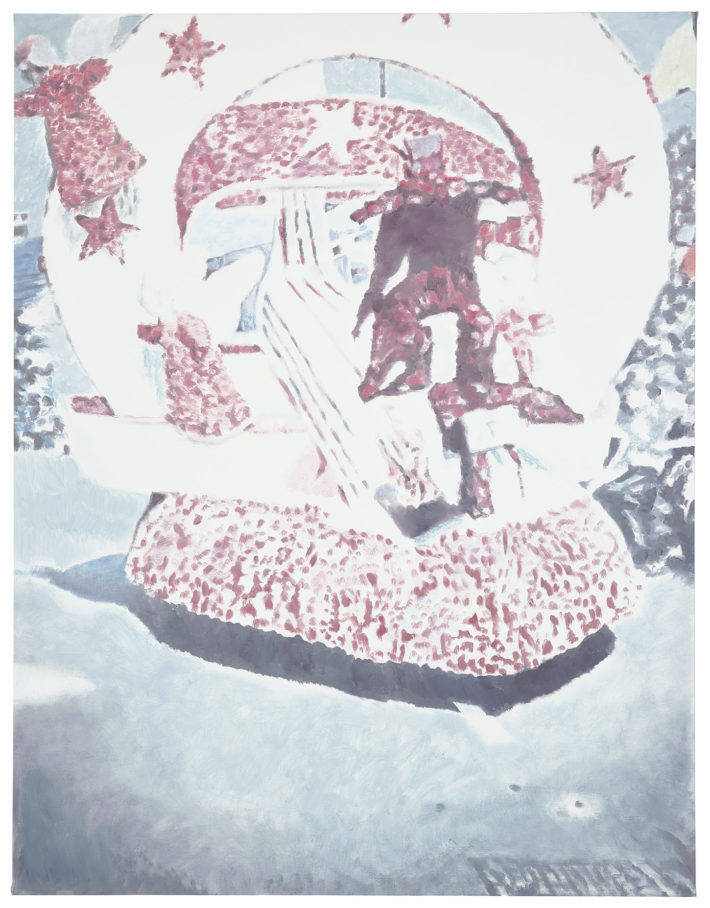

Luc Tuymans, Twenty Seventeen, 2017, oil on canvas, Pinault Collection. Photo: Studio Luc Tuymans, Antwerp.

Luc Tuymans, Corso II, 2015, oil on canvas, private collection. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London. Photo: Studio Luc Tuymans, Antwerp.

Notes

1 U. Loock et al. (eds.), Luc Tuymans (London: Phaidon, 1996, 2nd rev. ed. 2003), 112.

2 Caroline Bourgeois, in idem (ed.), Luc Tuymans: La Pelle, catalogue of the exhibition of the same name at Palazzo Grassi, Venice (Venice: Marsilio, 2019), 16.

3 Ben Eastham, “A Necessary Realism: Interview with Luc Tuymans,” Apollo: The International Art Magazine (October 2014).

4 Marc Donnadieu, in Luc Tuymans. La Pelle, guide to the exhibition of the same name, Palazzo Grassi, Venice, graphic design by Philippe Delforge (Lille: Les produits de l’épicerie, 2019), 18.

5 Jarrett Earnest, in Bourgeois (ed.), Luc Tuymans: La Pelle, 35.

6 Septembre Tiberghien, “La suspension du regard. Entretien avec Luc Tuymans,” H-art, no. 133 (2014), supplement in French, 5.

7 Luc Tuymans, presentation of the exhibition Luc Tuymans. Suspended – L’œuvre graphique (1989-2015) at the Centre de la gravure et de l’image imprimée, La Louvière, 2015.

8 Luc Tuymans, “On the Image,” in On & By Luc Tuymans, ed. Peter Ruyffelaere (London: Whitechapel Gallery/Cambridge, MA: MIT Press 2013), 50.