15 September 2017

Since the 1970s Hiroshi Sugimoto has produced a highly recognizable corpus of photographs: marine horizons, theaters, drive-ins and dioramas. Silent images, tending to essentiality and plucked from the flow of the time, that catch the eye as archetypes of a civilization still pervaded by a sense of eternity. Sugimoto’s photographic technique is always the same: the evocative power of the large format and the grace of black and white. But the artist is also known for his sculptures and his architectural projects, and in October will open his foundation’s arts facility, called the Enoura Observatory, in Odawara, an hour’s drive from Tokyo. We spoke to him at the Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, where his exhibition Le Notti Bianche, curated by Filippo Maggia and Irene Calderoni, is still under way.

Let’s start from the beginning. At high school you were interested in painting, and then you chose to take up photography. How did this change take place?

It happened after I graduated from the Art Center College of Design in Los Angeles, in California, in 1975. I was on my way to New York, I wanted to become an artist and I deliberately chose photography instead of painting. At the time, though, no one was using photography in the artistic field: the only possibility was to take up commercial photography, and that’s what I did. I worked as an assistant photographer for a few months and then realized that it was not my destiny. In the meantime I was coming into contact with the contemporary art scene in New York.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Teatro dei Rozzi, Siena, 2014. Summertime.

What exhibitions did you go to see in New York?

Dan Flavin, Ellsworth Kelly. I was interested in Minimalist Art, not the work of photographers.

In those years the hippie movements and many people of your age in general were fascinated by a spirituality traditionally associated with Eastern cultures and religions. Did the fact of being Japanese influence your relationship with American society?

Yes, and it was all new for me. In Japan I had attended a Christian school and so had never given much weight to the religious tradition of my country. Then I arrived in California and everyone there asked me about Buddhism. So I started to read a lot of books on the subject. I caught up on it.

Are you religious?

I think that art and religion have the same origins in the history of humanity, but I don’t practice any religion. For me art is more important. My artistic research investigates the mind and the moment at which we become aware, as human beings. Religion has a fundamental role in all this, because it looks into the spiritual aspect. Human beings have been very religious for most of their existence on Earth, then science emerged and over the last hundred years they have lost much of their spiritual bent.

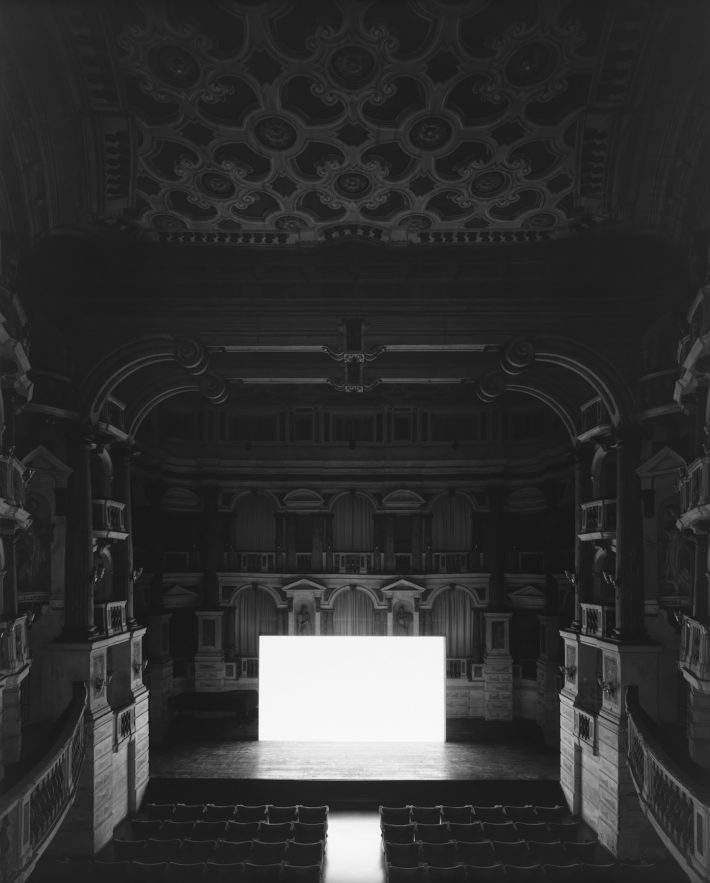

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Teatro Comunale di Ferrara, Ferrara, 2015. II Conformista (Screen side).

Do you believe that science has taken the place of religion in our society?

With the help of science people have begun to gain a better understanding of nature, a previously unknown part of the world whose control was associated with the presence of a deity. The truth is that that world is still today, to a great extent, unknown.

Your fascination with nature and the past is also reflected in your collection of fossils, meteorites and prehistoric finds. For a while you were even a dealer in antiquities. What is the point of contact with art, if there is one?

My method, as an artist, requires me to study myself. For this reason, I devote energy to my collection too. In addition, when I touch these objects I feel the passage of time.

Time plays a key part in your work: I’m thinking of the celebrated series of Seascapes and that of Movie Theatres, which you decided to go back to on the occasion of your exhibition at the Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo in Turin, entitled Le Notti Bianche [White Nights]. What has changed with respect to the first edition of the work?

At the beginning it involved showing a movie inside a theatre. The scene was ghostly and the only light came from the screen. I was in the middle, between the screen and the seats, but only the camera watched the movie: I set it up and went out.

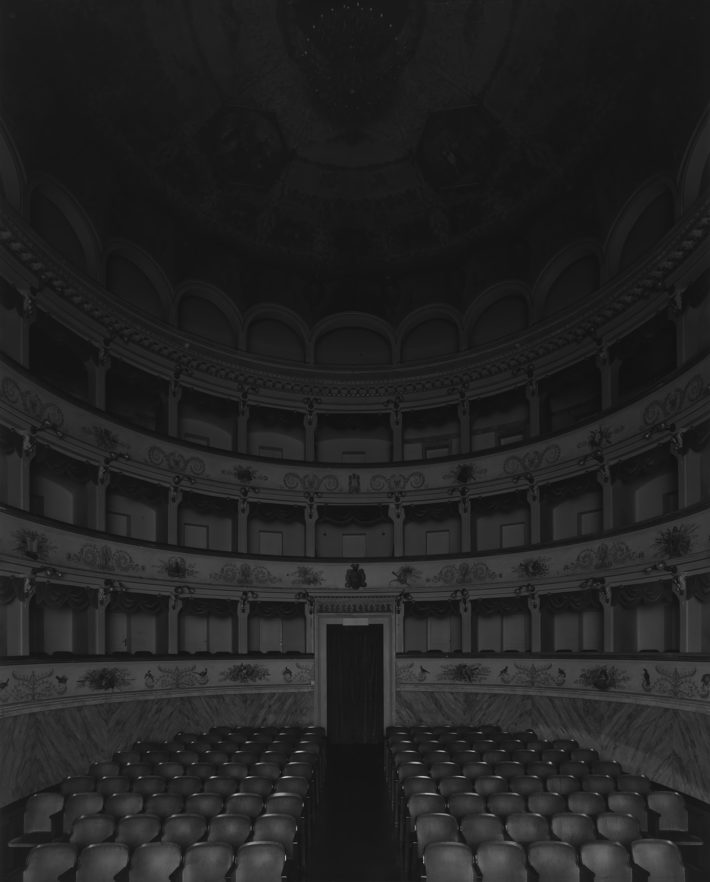

In this edition of Movie Theatres, after photographing stage and screen, for the first time you have turned the lens through 180° onto the seats and gallery, which are completely empty. Did you want to criticize the role of the viewer in today’s society, the use we make of instruments for the recording of reality?

The camera, the instrument in itself, is the only point of view: it looks, bears witness and vanishes. It is a concept of Duchampian inspiration. There are no others gazes because there is no audience, or they are invisible, defunct.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Ohio Theatre, Ohio, 1980. From the Movie Theatres series. Courtesy: Hiroshi Sugimoto.

I have read that at the entrance of your studio in Chelsea, New York, there is a photograph of Duchamp’s bicycle wheel, his first readymade, next to a print from the Theatres series. What does this juxtaposition signify?

Marcel Duchamp is one of my points of reference, all the early avant-gardes have had a great sway over me. The reason I associated the two images is that Duchamp has influenced me, while my work is there to keep an eye on the present, on contemporary reality. I think it is important to devote a lot of time to you own work, months or years, to examine it in depth before showing it to others. I want to give my work a strong presence, because it is from its presence that I judge a work of art.

If I think about your work and Duchamp’s I can see the affinity in their relationship with reality and its surmounting. Yours is also a conceptual art that tends to go beyond the present time.

Yes. When you look at Duchamp’s work you realize that it is often situated in the fifth dimension. As an artist I try to enter another space, outside of the present time. His art is very philosophical, it makes use of metaphor and often lacks explanations. His work is mysterious and poetic. I’m thinking of The Large Glass (1915-23): no one knows what is going on, and yet it grabs your attention. I go on looking at it, and it keeps its strong presence. I have learnt a lot from Duchamp.

Do you think that the art of today carries too much information?

It’s like wallpaper, and there’s a big difference between wallpaper and art.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Teatro all’Antica, Sabbioneta, 2015.

You take pictures with a film camera and print in black and white, two choices that you have never abandoned since the seventies. Not even after the digital revolution and the triumph of color. What do they mean for you today?

Digital photography is easy, while it is more and more difficult to carry on with analog photography, because film is hard to find and photographic paper is disappearing. I have to prepare my own paper and solvents, something I already did, but now I have no alternative. In my studio we do photography in the old way, and today this is even more important. I’m the last relic of this photographic tradition, and I’m proud of it.

I imagine there are other side effects, when you’re traveling, for example. How much does your equipment weigh?

My assistants carry over a hundred kilos. I don’t travel light.

And then analog photography, unlike digital, is the fruit of a process. How do you handle it?

Yes, and it is still the same process as was invented in 1839, even though we are in the 21st century. When I take pictures in theatres I set up a dark room to develop the photographs.

In a decade crammed with events for the history of photography, one that has seen destabilizing developments like the closure of numerous photographic agencies and the emergence of the social networks, vehicles of a completely new imagery, the debate over the status of the photograph has not only not challenged the value of your work, but has made it—if possible—even more decisive.

I don’t argue with the way the world is going. The world is changing, I stay myself. I think that photography has come to an end with the 21st century. Today there is a new instrument, a new language, but it is no longer photography. Photography, invented in the 19th century, was magic, it froze movement and recorded history. That status has been lost forever. Now you take a picture and then you alter it any way you want with Photoshop or some other program. Digital photography has little to do with reality, it’s just a clipping from our imagination.

When did “photography come to an end?”

In 2012, when Kodak declared bankruptcy. Kodak represented photography from its beginnings until that day. The daguerreotype was successful for a limited period of 4 or 5 years, but it was Talbot’s calotype that gave rise to photography, which lasted for 170 years. That’s a long time, if you think about it.

In October you’ll be opening a center devoted to art and performance at Enoura, an hour’s drive from Tokyo. It will be called the Observatory and house the offices of your Odawara Art Foundation. What role do space and time have in this project?

I envision the Observatory as a ruin, which will last much longer than me and perhaps even humanity. Another five thousand years, perhaps. It is a Parthenon, a dark room: it is the center from which to look at the world. It is located in front of the ocean, you can see the sea. It’s a special work of architecture, designed to frame the ideal viewpoint for solstices and equinoxes. I have called it an “observatory” because it combines art and astronomy. The beginning and the end of humanity imply vision, being present. How much time do we have left? I’m very pessimistic: from the capitalist perspective we are destined to keep growing, but this cannot happen. We have grown too much and too fast. Now we have to turn back.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Le Notti Bianche, Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, Turin.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Le Notti Bianche, Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, Turin.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Le Notti Bianche, Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, Turin.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Le Notti Bianche, Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, Turin.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Le Notti Bianche, Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, Turin.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Le Notti Bianche, Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, Turin.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Le Notti Bianche, Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, Turin.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Teatro Scientifico del Bibiena, Mantua, 2015. I Vitelloni (screen side).

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Teatro Scientifico del Bibiena, Mantua, 2015. I Vitelloni (seating side).

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Teatro Olimpico, Vicenza, 2015.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Villa Mazzacorrati, Bologna, 2015. Le Notti Bianche (screen side).

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Villa Mazzacorrati, Bologna, 2015. Le Notti Bianche (seating side).

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Teatro Goldoni, Bagnacavallo, 2015. Il Gattopardo (screen side).

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Teatro Goldoni, Bagnacavallo, 2015. Il Gattopardo (seating side).

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Teatro Comunale Masini, Faenza, 2015. Le Notti di Cabiria (screen side).

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Teatro Comunale Masini, Faenza, 2015. Le Notti di Cabiria (seating side).

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Teatro Farnese, Parma, 2015. Salò (screen side).

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Teatro Farnese, Parma, 2015. Salò (seating side).