2 July 2018

On Via Rovani, in Milan, there is an air of unnatural calm amongst apartment blocks that are more Austrian than Lombard, with their marble stairs, brass knobs and cast-iron elevators. Paolo Rosselli lives and works there as if “sunk to the bottom of a big city,” to quote a line from one of Paolo Conte’s songs, enveloped in the strong aroma of his Danish pipe tobacco. The conversation takes place in his photographic studio, under the vigilant gaze of a 19th-century lady along with a small and deserted Superstudio landscape and several cups of coffee.

A short time ago you presented at the Venice Biennale your latest book, A Talk on Architecture in Photography, published by Scopio Editions, which is a concentrate of your most recent work and above all a dialogue with Pedro Gadanho. How did this project come about? Portugal doesn’t seem to be a country with which you have any special ties.

It all started from an initiative by Pedro Leão Neto, who has launched a series of books devoted to individual artists, architects and photographers for Scopio Editions. In 2015 I was invited to hold a public talk at the Casa das Artes in Porto with Pedro Gadanho, who at the time was curator of architecture at the MoMA in New York and now is the director of the new MAAT (Museu de Arte, Arquitetura e Tecnologia) in Lisbon. In fact, I’ve only worked occasionally in Portugal, chiefly in 1998 to photograph the station at the Lisbon Expo designed by Santiago Calatrava, an architect with whom I collaborated a great deal in the eighties and nineties1. On that occasion I happened to meet José Charters Monteiro, a pupil of Aldo Rossi’s in Milan as well as his translator into Portuguese, with whom I later formed a close friendship, but that, as they say, is another story.

Pedro Gadanho, Paolo Rosselli, A Talk on Architecture in Photography: Photographs by Paolo Rosselli, Porto, Scopio Editions, 2018.

Reading it I find a number of constants, architecture of course, but also something that I don’t know if it can rightly be called a genre, the picture taken “from the car,” a kind of photography that you first embarked on with a film camera and then with a digital one. It doesn’t appear to me that this momentous technological transition has had much of an influence in your case, at least in this type of production. What do you think?

Yes, it’s true, the automobile or rather the view from the auto is a subject-image that goes a long way back. I think I must have started it in India, without any intention of making it a constant of my work. What I mean to say is that some of the ideas that characterize your photography often emerge unconsciously and it’s only after a long time that you realize that they’re there, obvious, almost crying out for attention. At that point you start to make adjustments or to ring the changes. I think this is linked to memory, a question that I also find fascinating: memory, it seems to me, is not something fixed, intentional, controllable, but a faculty that is reactivated when it is stimulated and remodels what is recalled. It’s a process that fascinates me because it regards not just the kind of memory studied in the neurosciences, but also—although in quite another manner—the digital kind. I moved to the digital more out of an interest of a perceptual nature than for technical reasons. Working on a photograph like the one of Jean Nouvel’s Torre Glòries in Barcelona, I realized just how superior the digital was technically, able to reach previously unknown levels of perception, without counting the multiple levels of analysis that I described in my book Sandwich digitale. At the same time, however, it should be said that the digital is turning into an almost ungovernable system owing to the quantity of data that it produces and accumulates. Digital memory is taking up more and more space, as the proliferation of data centers around the world shows.

Calcutta, 1981. Photo: © Paolo Rosselli.

Among the photographs in your Portuguese book, there’s one in particular that made an impression on me, one of the few not published previously: the picture in which you see part of the top of the Casa da Música designed by OMA sticking out amongst the roofs of the surrounding buildings. It struck me because it is a work of architecture famous for being totally decontextualized, as if it were a meteorite—Roberto Gargiani has compared it to a Suprematist tektonik.2 In your photograph, instead, it is mingled with the roofs of other buildings, almost contextualized by force, so that it is barely noticeable. Your picture deflates an established historiographical interpretation.

Yes, it looks like a scene created specifically to confute an interpretation. In reality, I was in my hotel and took the photo through a rather dirty window. I wasn’t interested in recontextualizing the Casa da Música, I just liked seeing it mixed up with all the rest. In my view the building works well in the Rotunda da Boavista because it provokes a rupture with its 20th-century fixity. I didn’t want to carry out a sort of reexamination of the Casa, only to show how the perception of a work of architecture changes in relation to the point from which it is viewed. I took a similar picture of Norman Foster’s 30 St Mary Axe in London.

Casa da Música, OMA, Porto, 2016. Photo: © Paolo Rosselli.

A while ago you told me that, in the eighties, when Luigi Ghirri happened to be in Milan, he used to come to see you every so often and tell you that what was needed was a photography of landscape, by which he meant the landscape of Italy, on which as is well known he was working along with other photographers and writers like Gianni Celati.3 You took up his suggestion, but focused your attention on other landscapes: India, for which you recently set up a website, and the Engadine,4 in Switzerland.

In reality I did work on the Italian landscape after Luigi died, but in a very particular way, comparing the black-and-white photographs of the Fratelli Alinari—Jacob Burckhardt’s collection on the historical monuments of Italy—with my own color pictures taken a century later.5 My first trip to India, on the other hand, was in 1979 and following that I didn’t have much contact with Italian photographers; I was almost always working abroad and was fairly out of touch, staying away for months on end. When I paid my first visit to India I was 27. I went there with Arturo Schwarz: I’d finished my architecture degree two years earlier, had worked in Ugo Mulas’s studio and made a trip to New York, on which I took photographs that I never published because I didn’t consider them ready. Immediately afterward I started to work on commission. It was with Arturo Schwarz, or rather thanks to his reputation as a scholar, that I published my first two books.6 Schwarz is an almost prodigiously intellectual man, an individualist with a strong personality. Among other things I remember that on the first trip to India we were joined by a common friend, Fernanda Pivano, who knew the country having been there several times, both with Ettore Sottsass and for her study of Allen Ginsberg’s work.7 And so, somewhat by chance, even my first published work as a photographer of architecture was Indian,8 on Chandigarh. First I ought to say that I knew hardly anything about Le Corbusier, except through books, because at my university—incredibly—he was considered an example not to be followed. Speaking in general, I think that India is unique owing to the presence of an extremely ancient past that coexists with a contemporary landscape. Elements of an archaic reality appear on every corner of the street as in no other part of the world. In this sense, the Indian street is a sort of training ground for perception, a concentrate of experiences that it’s impossible to find elsewhere. In Europe everything is more limited, compressed, and you no longer find this combination of superimposed signs. Going there often, in the seventies and eighties and later on too, I perhaps saw the globalized city a little earlier than others did: Mumbai and its boundless expanse of skyscrapers and slums, Calcutta and its decrepitude, a true visual explosion. New York in comparison is a much more basic city. Moving on to the so-called Italian landscape, and if you like its still unfamiliar charms, I recently showed in an exhibition at the Museo Nazionale Romano in the Baths of Diocletian a work on the area of Amatrice9—done at the invitation of Stefano Boeri. On that occasion I discovered, to give an example, that along the stretch of road that leads toward Lake Campotosto there is a sort of perfect environment—a true revelation, at least for me. The landscapes of China or India now have serious problems of pollution, they are compromised. But there is an unspoiled and delicate area between Lazio, Abruzzo and the Marche that recalls the background of a Leonardo painting.

Campotosto, Abruzzo, Italy, 2017. Photo: © Paolo Rosselli.

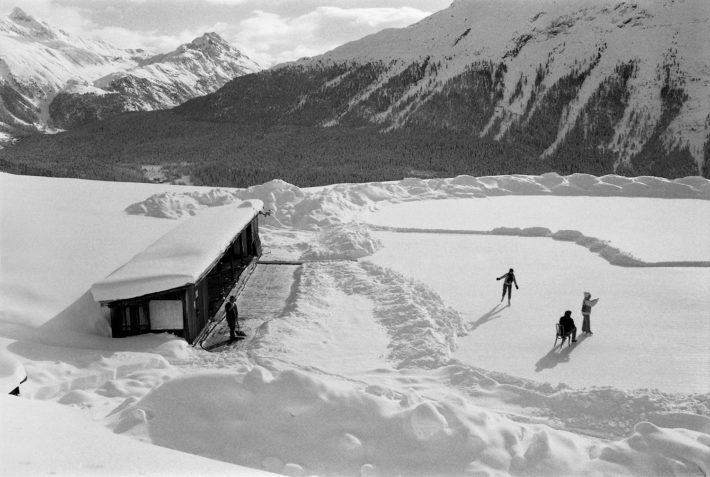

And the Engadine? I know that you’re working on a new book devoted to the same places, but over thirty years later, and I know too that it was right there that Rem Koolhaas got the impression that the countryside was undergoing radical changes10 For example, today it is full of chalets with no cows, renovated by architects from Milan to house things like art galleries.

If the Engadine has been well preserved it is largely due to the common sense of the Swiss and the active role of the state: as far as I know, the local farmers receive subsidies to take care of the landscape. The Engadine of today houses many art galleries in what were once farm buildings. There are contemporary works of art all over the place, in the parks and almost on the mountain sides. An important Swiss artist, Not Vital, puts his works on show amidst the nature of his park. And over the last thirty years a great architect, Hans-Jörg Ruch,11 has reclaimed and revealed the ancient structure of the Engadine house, reinventing it. My work is still in preparation, so I’ll pass over what is going to be published.

Muottas Muragl, Engadine, 1984. Photo: © Paolo Rosselli.

In general you cite very few photographers: Mulas in passing, almost more for autobiographical reasons; Ossip Brik for a conceptual aspect that is important to you. Your most significant references seem to be more literary: V.S. Naipaul, who brings us back to India, or J.M. Coetzee. Authors who may certainly have exercised a certain influence, but much more indirectly.

In just a few months Ugo Mulas taught me a great deal, as I wrote in one paragraph of Sandwich digitale. But writers, indirectly, affect me much more than photographers, I must admit, although it is not true that I’m not interested in the work of my contemporary photographer colleagues; on the contrary, as you know, I’m interviewing them one by one. I liked Lee Friedlander, for example, a lot when I was young because I found him visually complex and, at the same time, playful. I was particularly attracted to his visual construction, an aspect to which I still attach importance today, but I couldn’t tell you if I’ve really been influenced by it. I even have a signed copy of one of his books because about ten years ago I reviewed it for Domus.12 What I like about him is his elegant and uninhibited study of the composition of the image. But if there is one figure that deserves particular respect today it’s that of the writer; obviously, not all writers without distinction. I’m not particularly fond of negative literature, self-pitying litanies, novels that play footsie with their readers, whispering that the world is rotten. For the understanding of the world I can’t manage without books, without writers, without the words they choose, the pages, even the gaps they leave. Tolstoy in Anna Karenina may almost be better at teaching you to see than a photographer, as in his account of the horse race in St. Petersburg where he describes the scene from the viewpoint of both the onlookers and one of the riders. Writers have a highly developed sensibility that helps me to understand where and how I live today. The Life and Times of Michael K is an unsettling book13 by a great South African author, John Maxwell Coetzee, who’s a good match with William Kentridge. There’s an affinity between them that goes beyond their nationality, perhaps because they have both come out of a tragic situation that they have been able to tackle in an extremely generous, humane way. Then there are other, more humorous writers, like Saul Bellow, whom I’ve been rereading recently. The term humorous should not be misunderstood: as you know, even Kafka makes you smile at the beginning of Metamorphosis. Bellow for me is a truly wise man. In general, I’m drawn to playful writing and I think, or hope, that many of my photographs are a bit playful too. By the way, just between ourselves, who knows why in photography black-and-white has always been considered more “rigorous” than color? Could it be the usual simplification of self-styled critics? Going back to writers, if Coetzee is extraordinarily skillful, I also admire the lucidity of Joseph Brodsky’s essays. If I were a high-school teacher I’d certainly put them on the curriculum. Brodsky explains what the devil is life, art and writing. He’s incomparable.

Torre Glòries, Jean Nouvel, Barcelona, 2007. Photo: © Paolo Rosselli.

The first of your numerous books with which I was directly involved was the Terragni Atlas, published to mark the centenary of the great architect from Como and among other things the first you did after your shift to the digital—and realized without ever using a wide-angle lens.14 It’s a crucial book because it shows how the reexamination of a classic through photography can renew its interpretation and literally translate it for the future. Specifically, you rescued Terragni from the black-and-white image that characterizes so many exponents of the heroic period of Modernism, all of them regarded—wrongly—as purists because their works were published in magazines and books in black and white, as well as because of interpretations like Peter Eisenman’s conceptual and autonomist one. Instead your photographs showed us not only a Terragni in color, but also an architect who was in no way autonomous. On the contrary he was highly attentive to the context in which he placed the not very many of his projects that were actually built, almost all of them masterpieces. And as you rightly wrote at the time, “The photograph looks at, thinks about and translates the architecture; as a result, when seen, this starts to change.”

In every work you have to start from scratch, make a clean sweep. Usually I begin without selecting much; I look and that’s all, and above all I don’t practice self-censorship. Then little by little I put my discourse together without taking the work of those who have preceded me into account. That book on Terragni was also a way of clarifying things: at last we can judge him as an artist, setting aside the dispute over his ideological affiliations. I acted in the same way in the case of Brunelleschi, whom I tried to reassess in a highly compressed photograph of the cathedral viewed from a distance, in a Florence that for me retains an air of curious precariousness. In a certain sense the architecture of the past has the ability to repulse photography, to not admit it into its world. So much so that in Florence, immersed in the climate of the Renaissance in front of the Ponte di Santa Trinita, I waited for an oarsman to pass under the arches. It seemed to me to be the only way to bring a Michelangelesque bridge of the late Renaissance into the present day.

Gabriele Basilico, who like you studied architecture at Milan Polytechnic, acted in a diametrically opposite manner, scrupulously eliminating the human figure.

Gabriele took some very beautiful pictures and in a certain sense was a photographer who renewed a 19th-century tradition, using a view camera, great depth of field, black-and-white film; in short, something very close to Ezra Stoller. I always remember him with pleasure for his ability to make conversation, something that is truly rare. The human figure in photography is a recurrent subject of debate; many ask whether or not it should be there. It depends on the circumstances; the human presence in an image is essentially a form in its own right, one that enters into relationship with the other parts of the photograph. Including that presence means recomposing it and not putting it in there any old how.

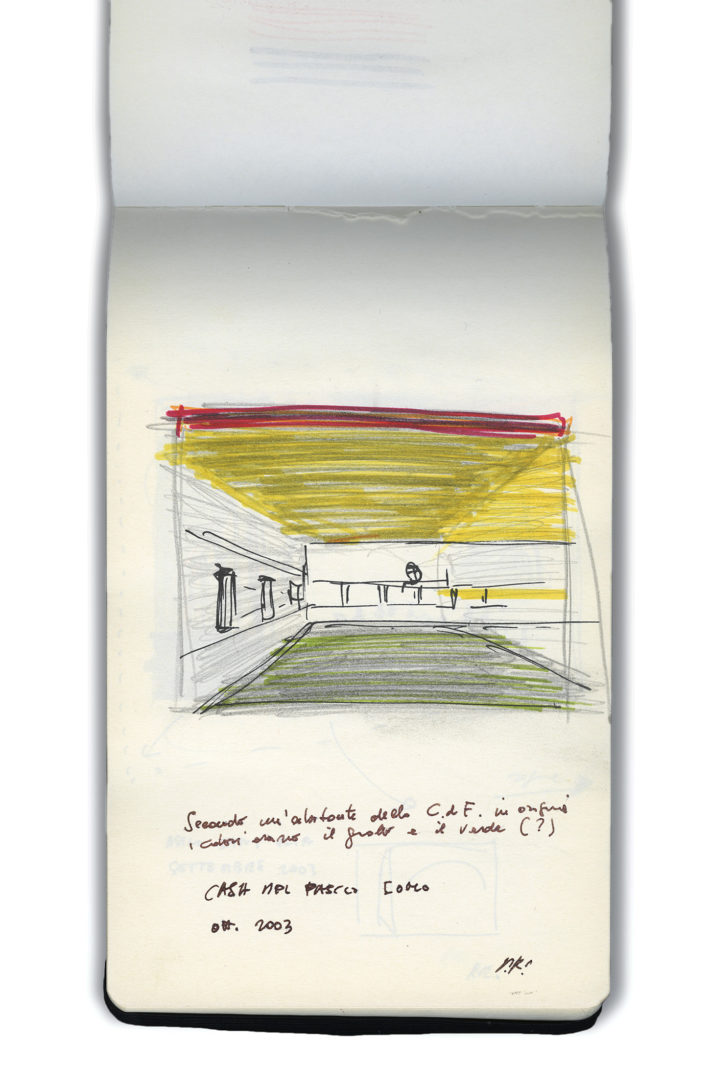

Terragni notebook, 2003. Drawing: © Paolo Rosselli.

The sketches with the framings of Terragni’s works from your notebook, published for the first time in the Portuguese book, have a lot to do with abstractionism, and I wonder if this comes naturally to you because you’ve always lived in contact with the abstraction of your grandfather Gio Ponti’s geometries or of figures like the historian of abstractionism Paolo Fossati, who worked with your father Alberto.

No, I don’t think so. Painting hasn’t had much influence on me, I prefer literary references as I told you. Nonetheless, Terragni for me didn’t just create architectural volumes, but something that has to do with a complex and, if I can put it this way, conceptual, abstract geometry. The ceiling of the Casa del Fascio in Como is not a simple ceiling, rather it is a structure on several levels; the staircase is a musical motif, the window is studied in its own right and as part of the composition of the façade. You can’t photograph Terragni’s work from a distance or as a whole, lest you lose everything. This is why I make sketches of the framings that came to mind in front of his buildings, or as a reminder, after I’d taken the pictures. Paring down the volumes by drawing them sometimes helps me to grasp the reality; the photographs I take are never the product of rational analysis, but of notes, of light glosses that are born out of an attentive but delicate state of mind.

Aren’t they somewhat ironic?

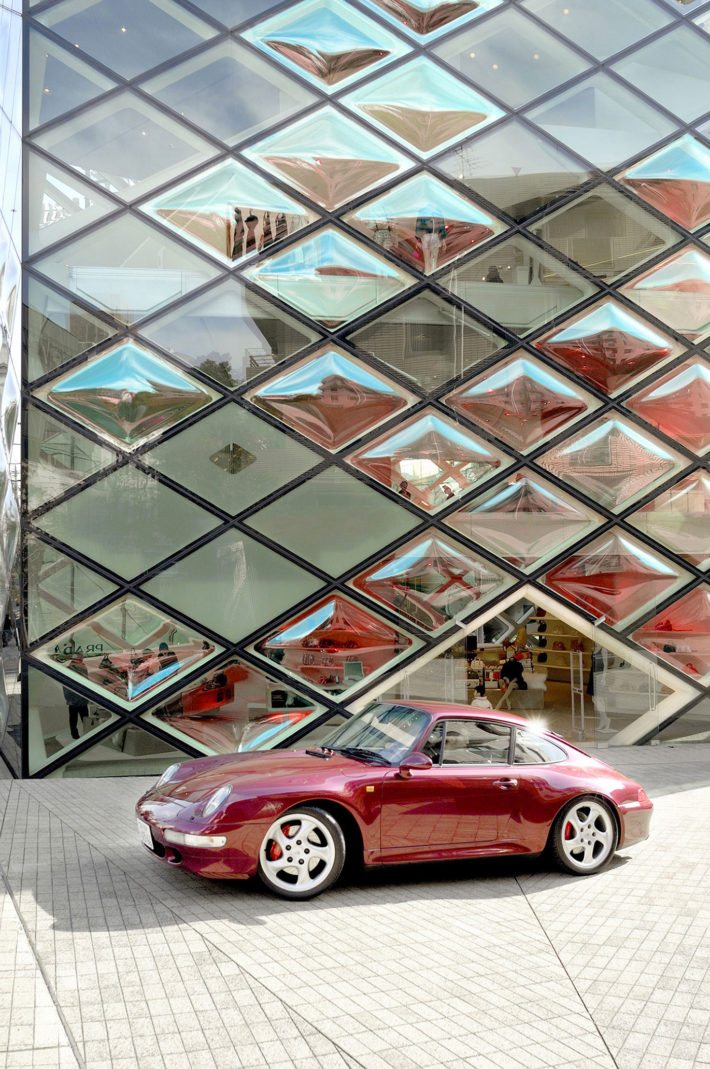

No, because irony is detached, it’s a rather cold attitude. I don’t want to unmask anything, I try to be—let’s say—balanced. When I’m in this state of mind photos like the one of the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao reflected in the window of a pastry shop, or of Herzog & de Meuron’s Prada store in Tokyo with an eggplant-colored Porsche that exalts the three-dimensional character of the glass façade come to me instinctively. Mine is not a nostalgic gaze, it is a gaze suspended in mid-air, poised between reality and play, in which I am not trying to demonstrate anything, and still less seeking to develop or serve up some idea. Theories are harmful to photography and I believe that the same is true for literature.

Your website Passages has been on line for a few months now. On it you’ve published a series of your video-interviews with some very different Italian photographers, from Alessandra Spranzi to Stefano Graziani. It seems to me an exploration that makes no value judgments. What are your precise objectives?

I have to say that I’m not interested in putting Italian photography in a historical perspective and still less in organizing a movement. What does interest me is to find out what is going on today, who are the people who practice this profession, this art, in order to express themselves. I choose both the person and his or her product, so there is a certain amount of selection and it’s natural that they are mostly photographers who gravitate around Milan. But in general it’s people I’m interested in, be they men or women, and not groupings or collectives. I make no distinction between someone born in 1940 and someone born in 1985, to be clear. I look at Italian photography with interest and think that it is neglected today—despite being of great value. This is because of a certain laziness on the part of critics as well as the people in charge of institutions. Besides, there’s no point in expecting any attention from the national policy on culture, which finds it hard to recognize what its functions are and is full of holes. So we might as well do it ourselves.

Casa del Fascio, Giuseppe Terragni, Como, 2003-04. Photo: © Paolo Rosselli.

Among your interviews there is one in particular in which you are often smiling, the one with Guido Guidi, a photographer whose background and poetics are at the opposite pole to yours.

Yes, it’s true, but Guido says things that I find clear, new and in a certain sense liberating. When I pointed this out to him he told me: “I didn’t say that.” And I said: “But you did, I just recorded it!” That’s why I’m smiling. Guido, for example, argues that Ghirri is Postmodern, while he is a Neorealist, at least in origin: I agree fully. And he adds: “I don’t like kitsch and so I don’t photograph it.” You can’t be any clearer than that. He is the proof of something that I’ve always thought, that the differences between generations count for nothing. There are people who at the age of 29 or 75 express their point of view unaffectedly without the usual tedious intellectualistic trimmings. Going back to Passages, I’ve thought about including non-photographers as well, like the comparatist Daniele Giglioli, and soon I hope to interview a neuroscientist too. This is because I’d like to overcome the idea that photography should be viewed principally from a historiographical perspective and seen as a sociopolitical phenomenon—I shudder at the thought. The photographers or artists, men and women, whom I’ve interviewed up to now move with an unprecedented freedom. In order to understand how the memory, the consciousness and the eye, seeing that we’re talking of photography, exchange ideas, recollections and representations, it is fundamental in my humble opinion to study how the brain works. As well as in order to start talking again about aesthetics, construction of the image, personal memory and how in the end it is instinct that creates the image, reconstructing reality from scratch. When I talk about this with scientists they look at me with a mixture of interest and astonishment.

Casa del Fascio, Giuseppe Terragni, Como, 2003-04. Photo: © Paolo Rosselli.

Town Hall, Norman Foster, London, 2010. Photo: © Paolo Rosselli.

30 St Mary Axe, Norman Foster, London, 2010. Photo: © Paolo Rosselli.

Vertical Forest, Stefano Boeri, Milan, 2014. Photo: © Paolo Rosselli.

St. Moritz, Engadine, 1984. Photo: © Paolo Rosselli.

Badrutt’s Palace Hotel, St. Moritz, Engadine, 1982. Photo: © Paolo Rosselli.

Villa Méditerranée, Stefano Boeri, Marseille, 2013. Photo: © Paolo Rosselli.

Calcutta, 1981. Photo: © Paolo Rosselli.

Prada Aoyama Epicenter, Herzog & de Meuron, Tokyo, 2006. Photo: © Paolo Rosselli

Guggenheim Museum, Frank Gehry, Bilbao, 2007. Photo: © Paolo Rosselli.

Notes

1 Paolo Rosselli, Santiago Calatrava: Public Buildings (Basel: Birkhäuser, 1996); id., Santiago Calatrava: Bridges (Basel: Birkhäuser, 1996).

2 Roberto Gargiani, Rem Koolhaas/OMA: The Construction of Merveilles (Lausanne: EPFL Press, distribuited by Routledge, 2008), 272-297.

3 Luigi Ghirri, Gianni Leone and Enzo Velati, eds., Viaggio in Italia (Alessandria: Il Quadrante, 1984).

4 Engiadina. Architectura ed ambiaint / Architektur und Umwelt / Architettura e ambiente, photographs by Paolo Rosselli (Chur: Verlag Desertina, 1985).

5 Paolo Rosselli, Das Italien Jacob Burckhardts (Basel: Architektur Museum Editions, 1997).

6 Arturo Schwarz, L’arte dell’amore in India e Nepal, photographs by Paolo Rosselli (Bari-Rome: Laterza, 1980); id., Il culto della donna nella tradizione indiana, photographs by Paolo Rosselli (Bari-Rome: Laterza, 1983).

7 Allen Ginsberg, Indian Journals: Notebooks, Diary, Blank Pages, Writings, March 1962-May 1963 (San Francisco: Haselwood/City Lights, 1970); Italian ed., Diario indiano, introduction, translation and notes by Fernanda Pivano (Rome: Arcana, 1973).

8 “Dell’India,” Lotus, no. 34 (1982).

9 Alessandra Acconci and Daniela Porro, eds., Rinascite. Opere d’arte salvate dal sisma di Amatrice e Accumuli, photographs by Paolo Rosselli, texts by Stefano Boeri and Paolo Rumiz (Electa: Milan, 2017).

10 Rem Koolhaas, “Countryside,” O32c, no. 23 (Winter 2012).

11 Hans-Jörg Ruch and Ludmila Seifert-Uherkovich, Historic Houses in the Engadin: Architectural Interventions (Göttingen: Steidl, 2009).

12 Paolo Rosselli, “L’America in fotografia / America in Photographs,” Domus, no. 881 (May 2005), 118-19.

13 J.M. Coetzee, Life & Times of Michael K (Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1983).

14 Attilio Terragni, Daniel Libeskind and Paolo Rosselli, Atlante Terragni. Architetture costruite (Skira: Milan, 2004); English ed., The Terragni Atlas: Built Architectures (Skira: Milan, 2004). See Manuel Orazi, “Translating Terragni,” Domus, no. 893 (June 2006).