4 October 2019

“The past does not exist, everything is simultaneous in our culture; all that exists is the present, in the representation that we make of the past, and in the intuition of the future,” declared Gio Ponti in 1957.1 It is a theory that seems to have inspired one of his illustrious colleague and contemporary Carlo Scarpa’s finest architectural interventions, the conversion of Palazzo Abatellis in Palermo into a museum, the seat of the Regional Gallery of Sicily. The museum, opened in 1954, still retains all of that innovative force today, and is now recognized as a masterpiece of the international museology of the 20th century. We can apply to Palazzo Abatellis Italo Calvino’s definition of the “classics” of literature since, like those books, this museum “has never exhausted all it has to say.”2

Photo: © Stefano Graziani, 2018.

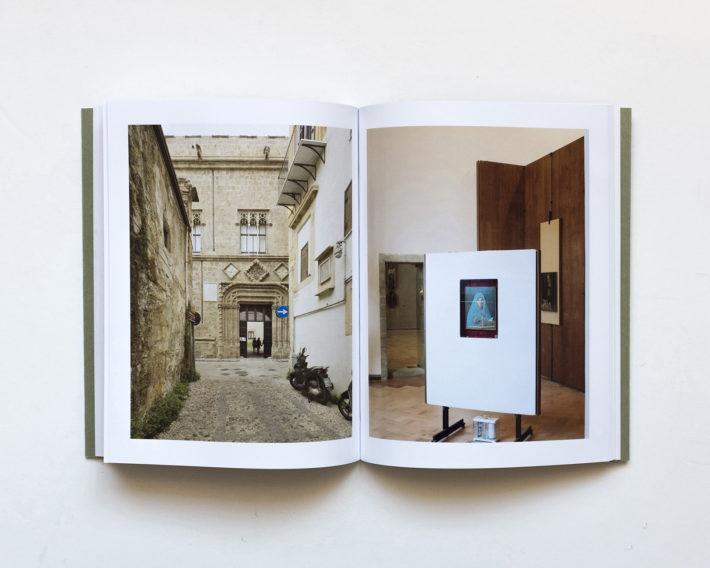

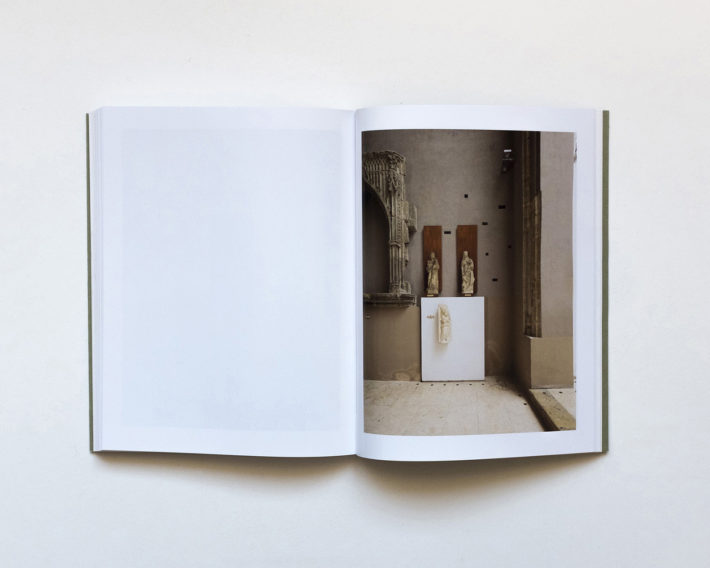

It is a great example of a groundbreaking public commission that continues to fascinate visitors and scholars with its ability to create ever new relationships between the architectural container (a building in Catalan Gothic style designed by Matteo Carnilivari in 1490), the masterpieces of art on display, the past eras in which the structure and the works were realized and their current enjoyment by a contemporary public. The museum space created by Scarpa is a device through which a dialogue is established between different moments in history, in the encounter between works and visitors. In Scarpa’s view, “to obtain something you must invent relationships,”3 and Palazzo Abatellis is a treasure chest of correspondences, like a piece of poetry. It is no coincidence that the museum has become the subject of a contemporary narrative, an artist’s book entitled Palazzo Abatellis Palermo, by Cloe Piccoli and Stefano Graziani. Published by Humboldt Books, it presents the insights not only of the authors, but also those of artists, architects, curators, scholars and art historians who have examined this unique place from a variety of perspectives. The publication is the end result of a participatory art project, “The Hidden City,” carried out a year ago as a collateral event of the European Biennial of Contemporary Art, Manifesta 12, held in Palermo in 2018 when the city was Italian Capital of Culture, in collaboration with the Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera in Milan and the Department of the Cultural Heritage and Sicilian Identity, the Polytechnic School of the University of Palermo, the Vincenzo Bellini Conservatory and the Accademia di Belle Arti of Palermo.

Photo: © Stefano Graziani, 2018.

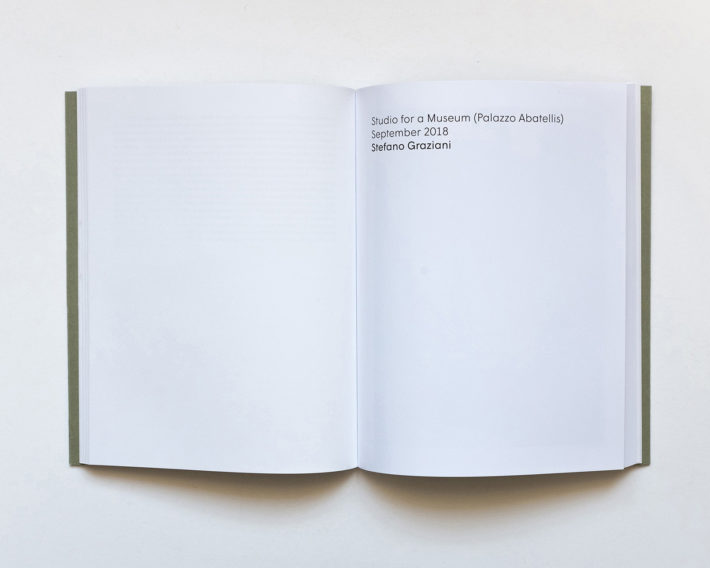

The idea of the curator, Cloe Piccoli, was to work inside one of the city’s old palazzi with a contemporary artist, Stefano Graziani, who uses photography as a means of narration, cataloguing and reinterpretation, and who investigates through his images the systems of archiving and conservation adopted in museums. The book has been conceived as a narrative, bringing out hidden elements and drawing attention to the different aspects of the place’s identity, at a time in which there is a tendency to level everything out and ignore differences. It is a line of research that falls within the purview of Institutional Critique, with “the aim of testing the very limits and potential of this museum,” writes Cloe Piccoli.4 The volume is the product of a research program that brought into Palazzo Abatellis thirty students from all over Italy selected through a public contest and thirty representatives of cultural professions from various countries for a discussion of the contemporary vision of the museum, observed from various points of view. A guide sui generis that looks, from a modern perspective, at one of the many precious but little-known sites in Palermo, metaphor for a hidden city (as the title of the project declares) still to be explored in all its complexity. A collaborative diary whose most immediate impact is provided by the images of Stefano Graziani, which fill a void as there is no extensive visual documentation of the museum, not an easy place to photograph. Graziani took his pictures on a Monday morning in September 2018, at the first light of dawn, with the museum closed and its director Evelina De Castro collaborating in and coordinating the whole process. The photographer asked to make a tour of the museum with the lights turned off together with all the participants: turning the lights off was a simple and radical act that gives us an insight into the point of view adopted by Carlo Scarpa, whose idea had been to display the objects under natural illumination and who “took the movements of the heavenly bodies, the moon and the sun, into consideration when studying the light in his projects,” explains Piccoli.5

Photo: © Stefano Graziani, 2018.

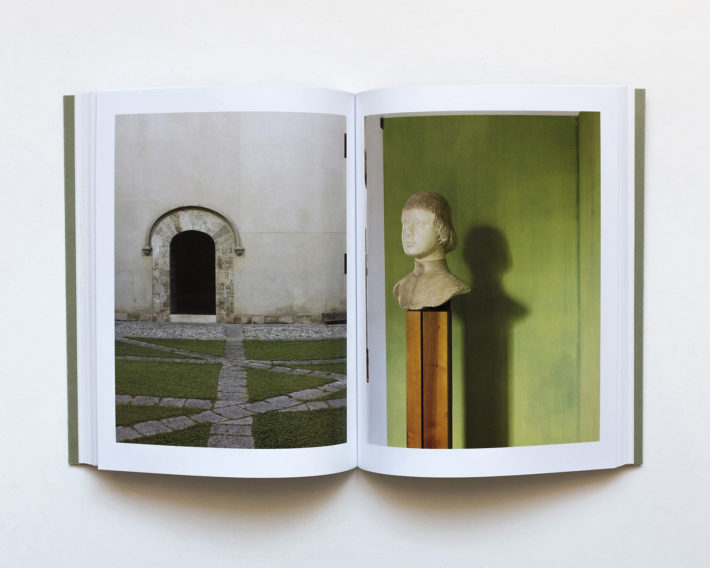

Graziani’s pictures home in on architectural details of the building, both the ones which are right in front of our eyes but we do not notice and the ones that are not normally visible: the urban setting of Via Alloro, heart of the Arab quarter of the Kalsa by the sea, close-ups of the materials chosen by Scarpa for the display, the finishes of the works, the blades of light and shade on the columns or coming from the openings of doors and windows, the courtyard decorated with three-light windows with slender mullions that provides a break between one story and the other of the museum. And again: the Renaissance head of a page sculpted by Antonello Gagini which turns its back on the window and the light that comes through it, while its delicate profile is silhouetted against a panel of dark wood on the wall. Followed by: the majestic fresco depicting the Triumph of Death which Scarpa inserted by expanding the wall of the chapel adjoining the building, the racks designed by Scarpa for the storeroom, the restoration workshop inside the museum and the archive of drawings by the Venetian architect, characteristic of his modus operandi: “I can only see things if I draw them.”6

Photo: © Stefano Graziani, 2018.

Graziani’s reflection on the ambiguity of this display in his interview with Cloe Piccoli is interesting. Scarpa’s inventions prompt the photographer to raise a number of questions. With regard to the room that houses Antonello da Messina’s Virgin Annunciate he asks: “Why is there a hexagon behind the gonfalon; why is there a passe-partout framing Antonello, or even why add a wooden partition that makes the room feel smaller than it is? We wonder why the altarpieces are hinged to the wall, or why in the entrance there are pedestals that display a number of isolated items. These are questions that may be left pretty much unanswered; I like to think that these compositions were the upshot of a stratification and a density of thought. Thoughts that in turn are capable of generating further questions and of proposing new interpretations. This intensity, which resists and which continues to give off energy, is the achievement of an enormous ambition.”7 Many people have tried to come up with answers to these questions, including the architect Santo Giunta, author of another stimulating essay8 on Scarpa’s work at Palazzo Abatellis. Piccoli and Graziani’s book continues with a contribution from Philippe Duboÿ, an architect and art historian who was an assistant and friend of Carlo Scarpa and is an expert on his work, that presents a series of firsthand accounts by people involved in the intervention in the fifties: from the writings of the Venetian architect himself to statements by Giorgio Vigni, head of the Galleries and Artworks Service for Sicily. Declarations that allow readers to form their own idea—reading the sources—of the context from which stemmed the museum’s display, intended to be itself a “work of art” that bears “the mark of its organiser,” in the words of Willem Sandberg,9 director of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, who had discussed these matters with Scarpa himself.

Photo: © Stefano Graziani, 2018.

The tone of the volume changes with the texts written by three contemporary artists, Massimo Bartolini, Simon Starling and Luca Trevisani, who propose their personal and tangential visions, each according to his own sensibility. Bartolini has the viewpoint of the sculptor who harbors a passion for Francesco Laurana’s marble funerary bust of Eleonora of Aragon, the same age as Palazzo Abatellis itself, and admires the brilliant way Scarpa has positioned it, so that the lady seems to be offered on an ebony tray at the height of the visitor: “I have always felt a strong impulse to place an arm around Eleanor’s neck, and even (I do not recall whether I actually did so) to give her a kiss. She was at just the right height and I could get up close.”10 The British artist Simon Starling came to the museum as part of his research into Caravaggio, and thanks to the collaboration with Evelina De Castro discovered the existence in its storerooms of a contemporary copy of Merisi’s Beheading of St. John the Baptist, the original of which is on Malta, which became the starting point for a new installation that he created for Manifesta 12. Luca Trevisani is the artist who has spent most time in Palermo and who came back to visit the museum, “a must for countless architectural pilgrimages,” to find an “oasis of silence and peace in the midst of that exuberant jungle” that is the Sicilian capital. Trevisani defines Palazzo Abatellis as an “exquisite combinatory poem,” a “wonderful carousel of which the delicate organisation tells us things that no critic has ever come around to saying: just how much art is made up of objects and pretence, and how much these imagined realities are changeable and changing, a far cry from any sense of fixedness or authorial desire.”11

Photo: © Stefano Graziani, 2018.

The pages of the book continue with testimonies from the experts invited to take part in the meetings open to the public held in front of the large fresco of the Triumph of Death, in one of the museum’s most fascinating rooms. They include architects (from Kersten Geers to Simona Malvezzi, Angelo Lunati, Emanuel Christ and Tim Power), historians and scholars like Margherita Guccione (who has studied the drawings in Scarpa’s archives at the MAXXI), Guido Beltramini and Maria Vittoria Capitanucci and photographers like Giovanna Silva, who is also the publisher of the volume. An account that opens up new perspectives on the way in which it is possible to relate to an institution like the museum, examining its unique character from the viewpoint of current sensibility. A methodological approach similar to the one put into effect by the team of Manifesta 12 with regard to the city of Palermo, setting in motion a process of redefinition through contemporary culture.

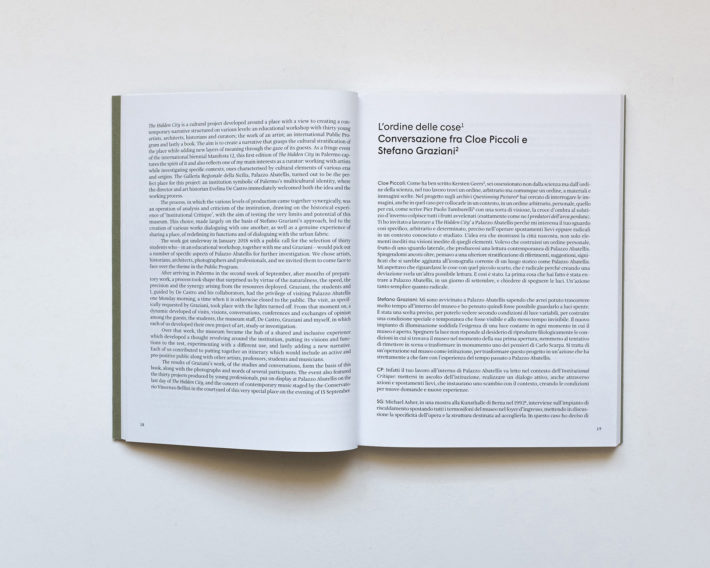

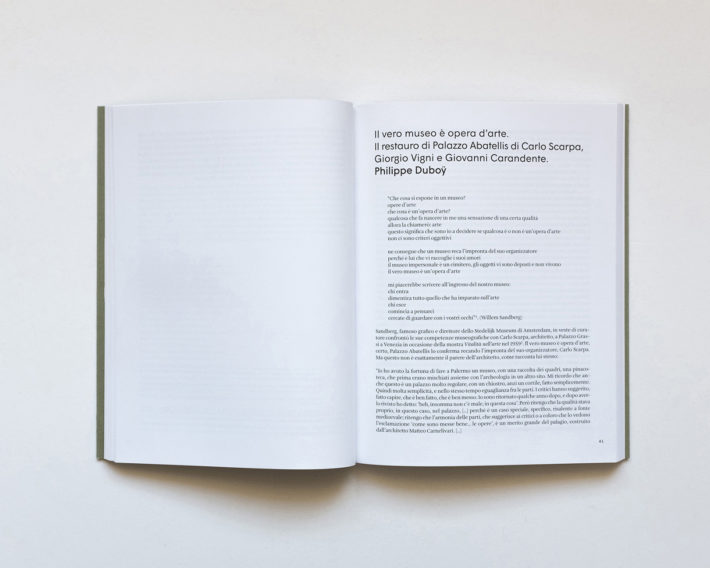

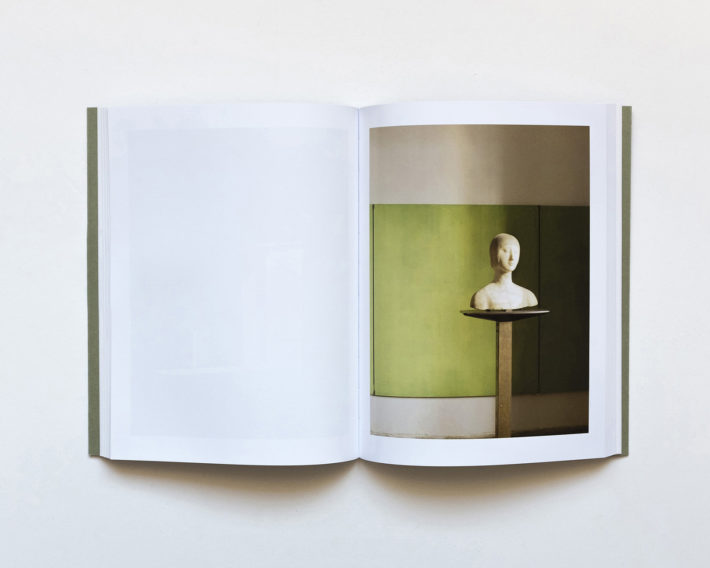

Photo: © Humboldt Books, 2019.

Photo: © Humboldt Books, 2019.

Photo: © Humboldt Books, 2019.

Photo: © Humboldt Books, 2019.

Photo: © Humboldt Books, 2019.

Photo: © Humboldt Books, 2019.

Photo: © Humboldt Books, 2019.

Photo: © Humboldt Books, 2019.

Photo: © Humboldt Books, 2019.

Photo: © Stefano Graziani, 2018.

Photo: © Stefano Graziani, 2018.

Photo: © Stefano Graziani, 2018.

Photo: © Stefano Graziani, 2018.

Photo: © Stefano Graziani, 2018.

Photo: © Stefano Graziani, 2018.

Photo: © Stefano Graziani, 2018.

Photo: © Stefano Graziani, 2018.

Photo: © Stefano Graziani, 2018.

Notes

1 Gio Ponti, Amate l’architettura: L’architettura è un cristallo (Genoa: Vitali e Ghianda, 1957), quoted here from the recent reprint (Milan: Rizzoli, 2015), 93.

2 Italo Calvino, Perché leggere i classici (Milan: Arnoldo Mondadori, 1991), 13. English ed., Why Read the Classics?, trans. Martin McLaughlin (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014), 5.

3 Carlo Scarpa, “Arredare,” master class held on March 18, 1964, at the IUAV in Venice, in Francesco Dal Co and Giuseppe Mazzariol (eds.), Carlo Scarpa. Opera completa (Milan: Mondadori Electa, 2001), 282.

4 Cloe Piccoli and Stefano Graziani, Palazzo Abatellis Palermo (Milan: Humboldt Books, 2019), 18.

5 Piccoli and Graziani, Palazzo Abatellis Palermo, 29.

6 Edoardo Gellner and Franco Mancuso, Carlo Scarpa e Edoardo Gellner. La chiesa di Corte di Cadore (Milan: Mondadori Electa, 2000), 38.

7 Piccoli and Graziani, Palazzo Abatellis Palermo, 28.

8 Santo Giunta, Carlo Scarpa. Una [curiosa] lama di luce, un gonfalone d’oro, le mani e un viso di donna. Riflessioni sul processo progettuale per l’allestimento di Palazzo Abatellis, 1953-1954 (Venice: Marsilio, 2016).

9 Piccoli and Graziani, Palazzo Abatellis Palermo, 45.

10 Piccoli and Graziani, Palazzo Abatellis Palermo, 37.

11 Piccoli and Graziani, Palazzo Abatellis Palermo, 61.