15 November 2019

Every family has a story to tell. The story of the Loys is one of a family of distinguished intellectuals which despite its fame has maintained a discreet reserve, far from the excesses of the media. And that of Giuseppe Loy, in particular, is the story of an amateur who took photographs all his life, leaving behind an archive of thousands of negative and prints that has yet to be fully explored. Giuseppe Loy, younger brother of the well-known movie director Nanni Loy, was born in Cagliari in 1928 and moved to Rome in 1938. After studying law, he followed for a while in his brother’s footsteps and entered the world of cinema, taking on the role of production assistant for several movies. In 1954 he married Rosetta Provera, known to the literary world as Rosetta Loy, author of the award-winning novel Le strade di polvere (translated into English as The Dust Roads of Monferrato). In November 1965, the Einaudi bookstore on Via Veneto in Rome hosted the first exhibition of Giuseppe Loy’s photographs. Antonio Arcari, who wrote an article on the exhibition for the journal Foto Magazin,1 described it as an exception in the world of Italian photography, with Loy’s pictures standing out for the authentic freshness of gaze of someone who takes photographs out of passion and not as a profession. Giuseppe Loy, who ran the construction company owned by his wife’s family, took an unconventional approach to photography, one not connected with amateur circles and free from the constraints of the profession. Photography would be his companion throughout his life.

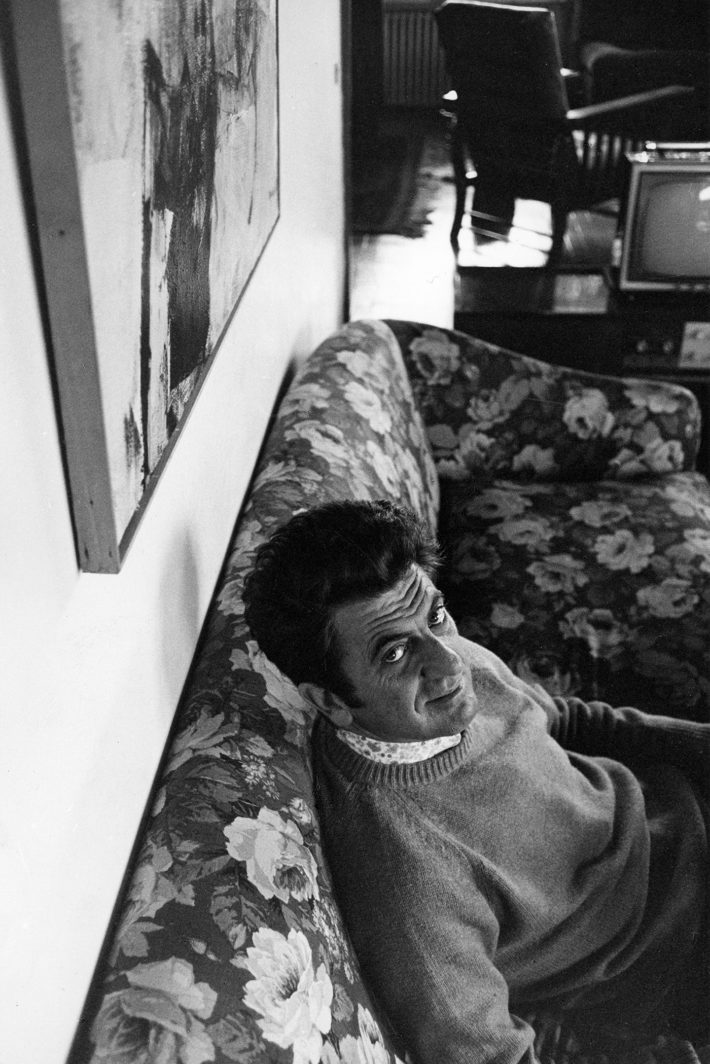

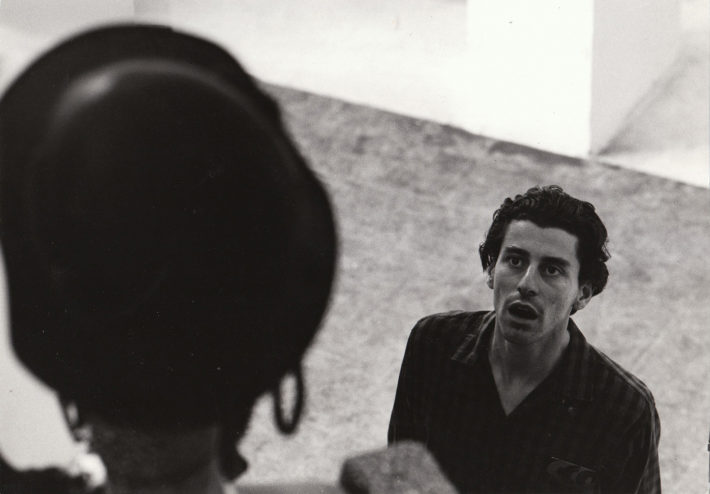

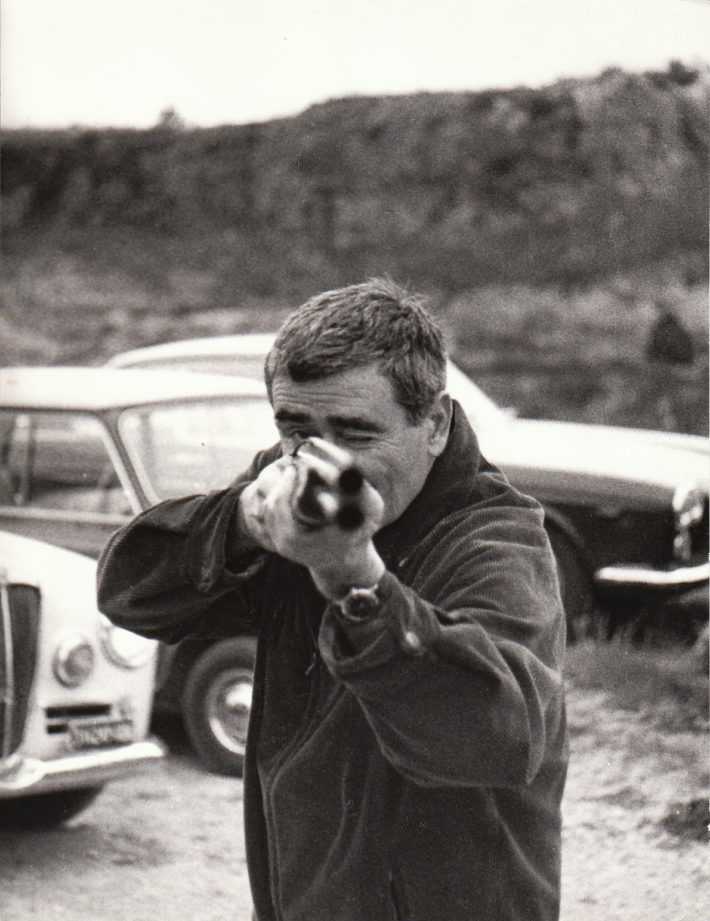

Nanni Loy, 1970. Photo: Giuseppe Loy, © Archivio Giuseppe Loy.

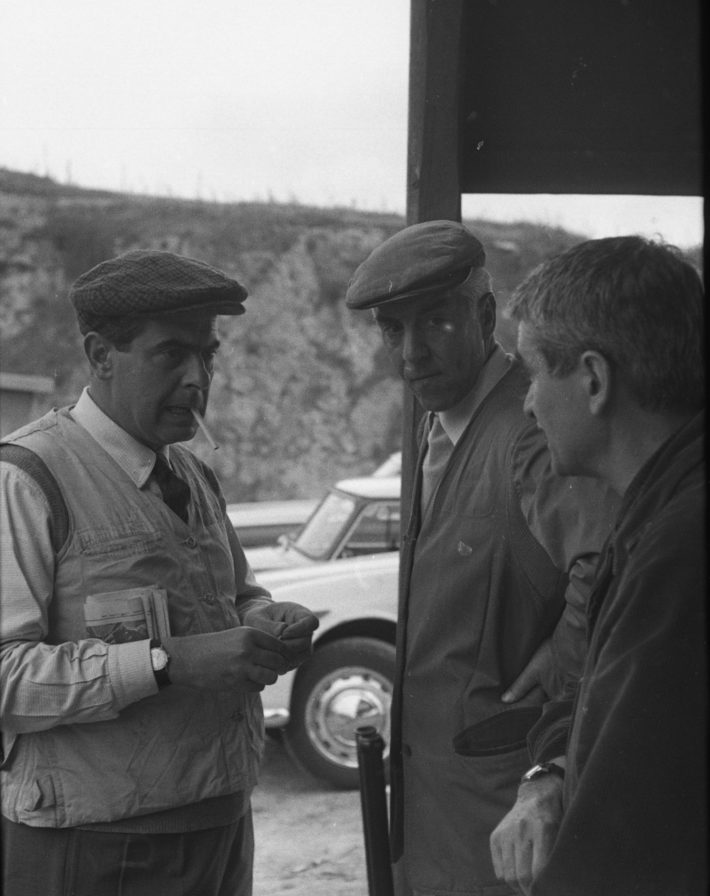

Almost forty years after his death, despite the prominence of his family’s name on the Italian intellectual scene, few are aware of the richness of the archive of photographs he built up over the course of his life. Thousands of negatives and more than three hundred prints are carefully preserved in the large family home on the outskirts of the city of Rome, where Rosetta still receives visits from guests, whom she greets by placing at their disposal copies of books accumulated over the years and laid out on a large pool table. It was only after Giuseppe Loy’s premature death, in 1981, that the great quantity of material was partially organized in view of a planned book, Il mare degli italiani, that was to have been published by Laterza but never came out. The photographs themselves were shown in 2014, in the exhibition Questa è la tua lezione, held at the historic bookstore on Via Sulis in Cagliari, the city of Loy’s birth. While justice has not yet been done to the quality of Loy’s photographic work in terms of exhibitions, some now well-known pictures—portraits of his friends Alberto Burri, Lucio Fontana and Afro Basaldella in their respective studios—have found their way out of the archive, linking Loy’s figure to the masters of Informalism.2 It is with Burri in particular that the photographs of Giuseppe Loy are often associated.3 With Afro and Burri, who by chance was a neighbor of the Loys at the time, Giuseppe shared a passion for clay pigeon shooting. A playful shot of Burri aiming his gun at the photographer evokes the afternoons spent by the friends at the range on the Via Tiberina.

From left to right: Giuseppe Loy, Afro Basaldella and Alberto Burri at the clay shooting range on the Via Tiberina, Rome, 1967. Photo: unknown photographer, © Archivio Giuseppe Loy.

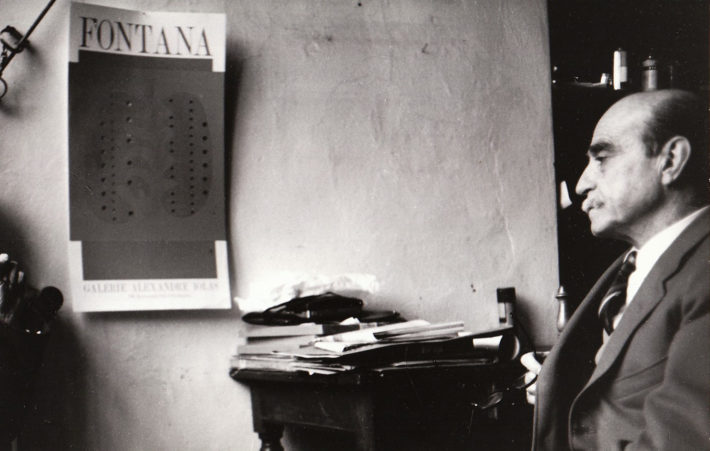

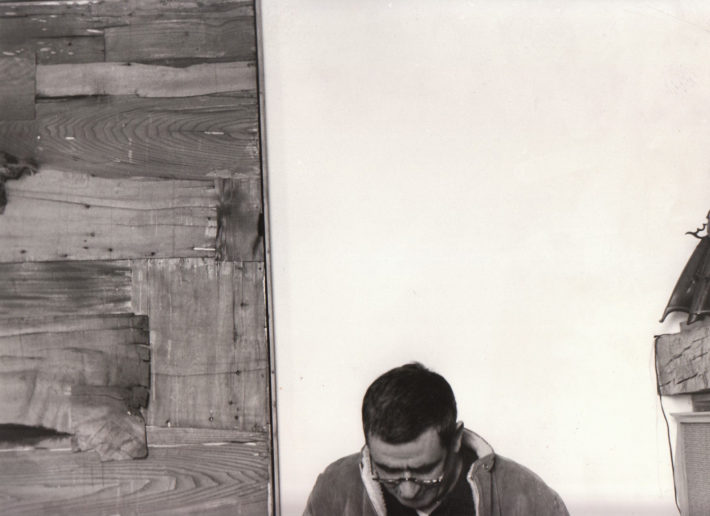

A recent exhibition4 at the Fondazione Palazzo Albizzini—Collezione Burri in Città di Castello paid tribute to the friendship between Burri and Loy, presenting the work of the principal photographers who have portrayed Burri in different periods and circumstances of his life, including Giuseppe Loy and some other famous names, from Gabriele Basilico to Ugo Mulas. Quite apart from the interest that this series of photographs stirs because of their subjects, Loy’s stylistic hallmark is revealed in their faces and their gestures. To the theatrical imagery of the artist in his studio, the photographer preferred minimal hints, small details, fleeting expressions. Hundreds of intimate pictures portray the artists in moments of repose and contemplation or in the simplicity of their daily work. Loy broke with the almost mythical tradition of the painter and the sculptor in their studios, favoring instead more spontaneous images of what for him were, first of all, close friends. Such an approach contrasts, for example, with the sophisticated theatricality of the series of photographs taken of Lucio Fontana by Ugo Mulas. The reflection on the process of artistic creation by which Mulas set great store, so that his pictures in sequence emphasize the different phases (meditation, execution and contemplation after the act of creation),5 is ignored by Loy, its place taken by a representation of the studio as an intimate and domestic setting, the place where the artist lives, thinks and creates. A picture of Fontana with an absent-minded expression on his face in front of the poster for one of his exhibitions and an untidy pile of papers provides confirmation of Loy’s distance from traditional iconography and his lack of interest in an elaborate setting of the scene.

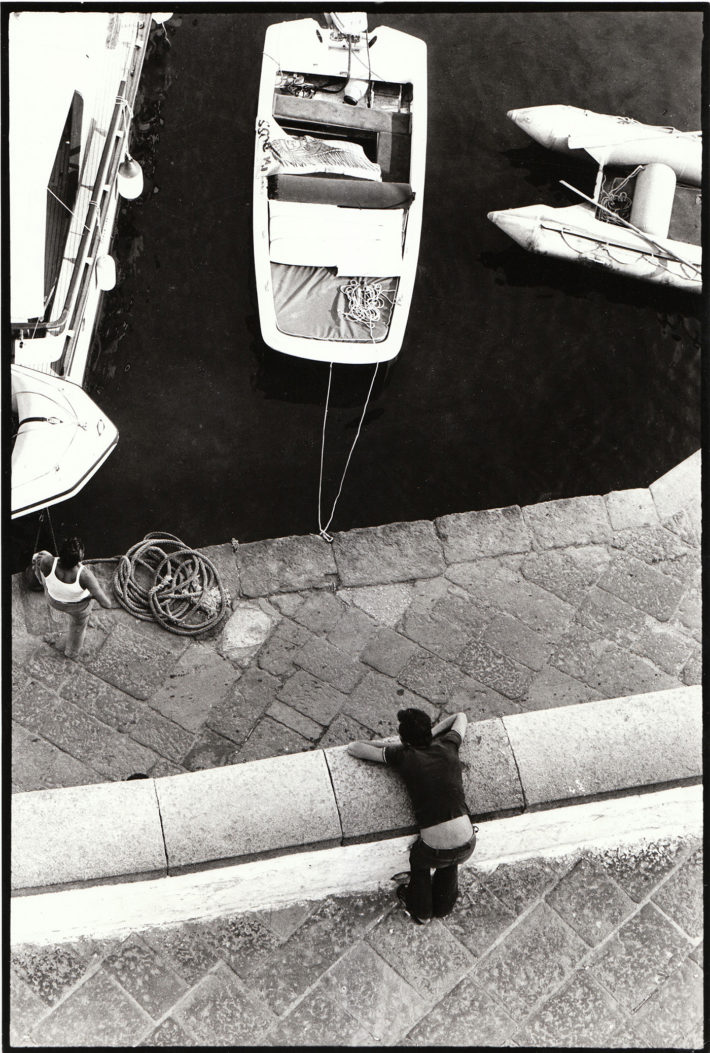

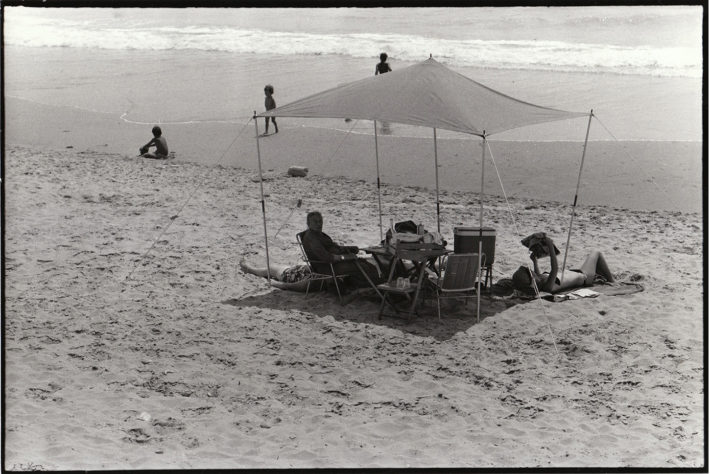

Ponza, 1973. Photo: Giuseppe Loy, © Archivio Giuseppe Loy.

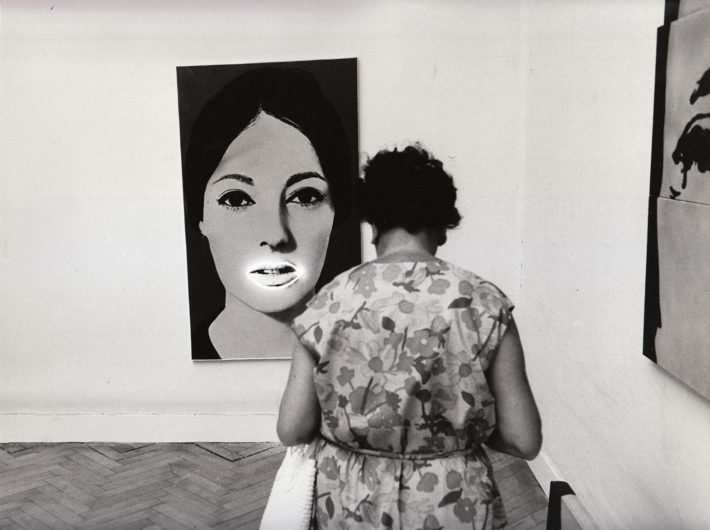

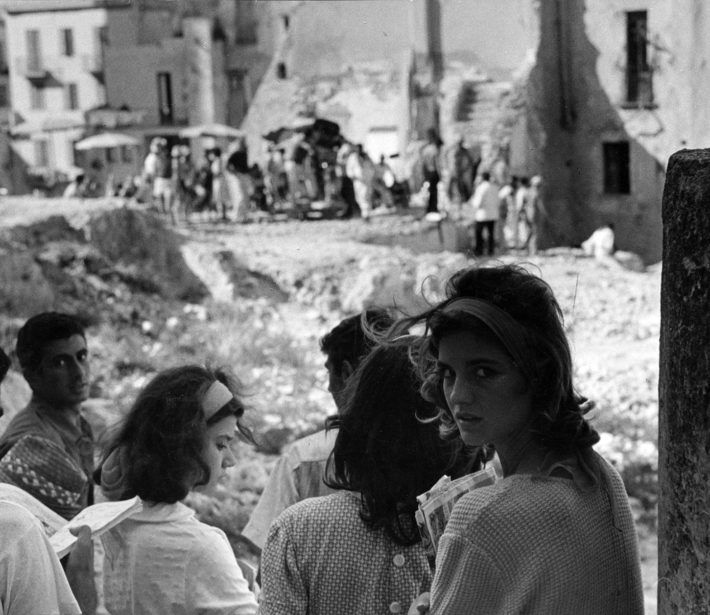

Simple, therefore, is the adjective that best describes the world viewed through Giuseppe Loy’s lens. At the 1966 Venice Biennale, in which Burri, Fontana and Afro all took part, Loy did not miss the opportunity to capture the expressions of visitors perplexed or astonished by the forms of contemporary art. There is always a touch of irony in his works. He turned his lens this way and that among the pavilions of the Biennale, focusing here on the exaggeratedly shocked and comical expression of a young man in front of a sculpture, there on the flower-printed dress of a woman gazing at Martial Raysse’s work High Voltage Painting, creating a fortuitously Pop composition. What has not been made sufficiently clear up to now is that Giuseppe Loy’s photographic adventure went well beyond his friendship with Burri, Fontana and Afro, and the archive is the testimony to what Loy himself defined as the “visual notes” of a life devoted to his passion for the medium. It contains hundreds of marvelous pictures taken in the places frequented by Loy and his family, from the mountains of Ortisei to the beaches of the coast near Rome and Civitavecchia, where the ferry departed for his birthplace Cagliari. These photographs, hardly any of which have been published, tell the story of a family and, if viewed from a broader perspective, reveal a great deal about the Italian society that Loy knew, of which he was a witness and in his own way a commentator. Without yielding to the temptation of spectacularization, Giuseppe Loy’s pictures are an original documentation of Italy between the end of the fifties and the beginning of the eighties.

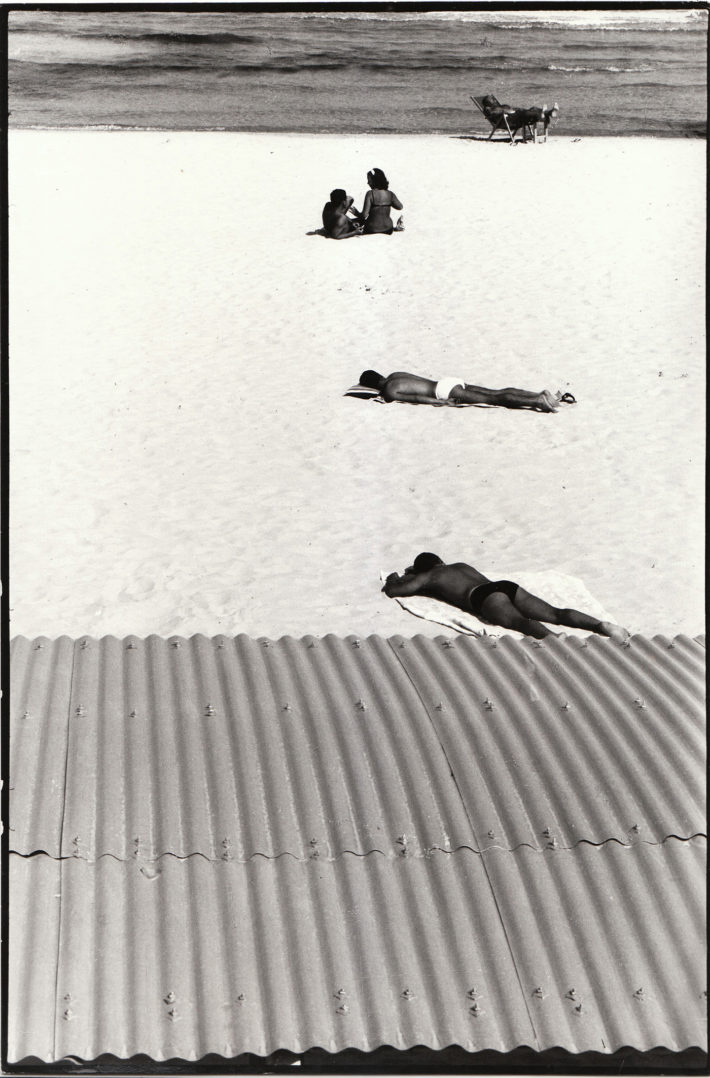

Ostia, 1960. Photo: Giuseppe Loy, © Archivio Giuseppe Loy.

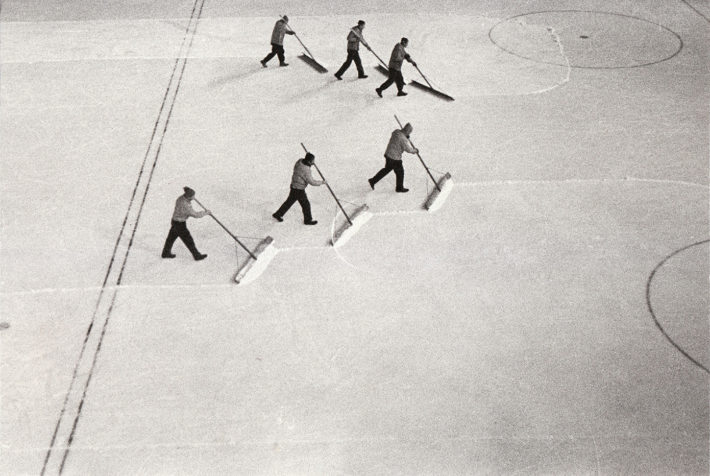

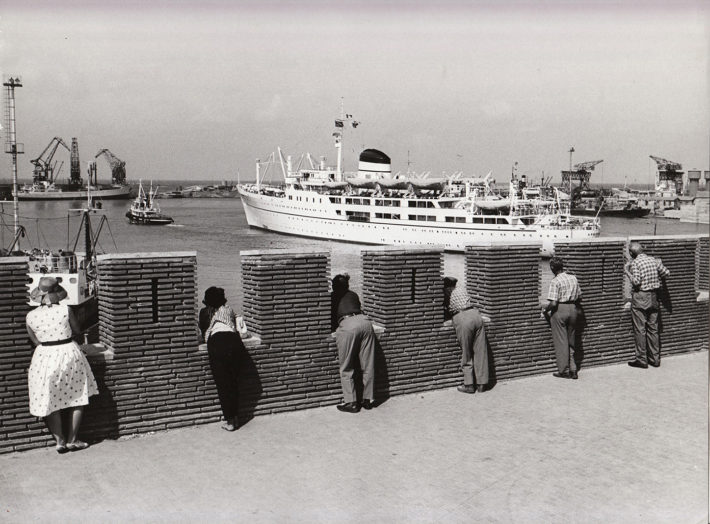

A recurrent presence in Giuseppe Loy’s photos is the sea, an element that recalled his childhood in Sardinia, of which he cherished an almost mythical memory. The seaside immortalized by Loy is the mainland coastline of departing ferries and reunited families: Ostia, Ponza, Civitavecchia, Sperlonga, Santa Marinella and the Calabrian coast are some of the locations he most frequently portrayed. Banal scenes and moments of ordinary life were ennobled with no hint of voyeurism by Loy’s camera, which favored elevated and sometimes daring points of view, fascinated by the presence of artificial constructions along the country’s shores. Loy’s sea is never a solitary sea; nevertheless, while on the one hand the scenery is dotted with beach umbrellas and deckchairs, on the other his attention is drawn to the contemplative appeal of the sea: a young man leans over the wall of Ponza harbor and gazes raptly at the bustle of the sailors; some people watch as the ferry leaves the port of Civitavecchia, perhaps saying goodbye to their loved ones for the last time. The serenity conveyed by Loy’s pictures is reminiscent of the masters of the French school: from Henri Cartier-Bresson’s photographs of the congés payés, the “paid vacations,” in 1936, to the carefree antics of Jacques Henri Lartigue’s bathers on the beaches of Biarritz. Rosetta Loy remembers her husband as an ironic man, and so are his photographs, from which the enjoyment he derived from his passion emerges clearly. Looking through Loy’s archive, what you find is a whole range of images that are united by a pure and disinterested delight in taking pictures. The vacations in the mountains with his family were an interlude of joy and relaxation, which he immediately turned into an opportunity for creative research. Loy explored the aesthetic possibilities that the mountain setting offered, spurning the clichés of landscape photography and drawing inspiration instead for some of his most conceptual works. The photographs taken at Ortisei in South Tyrol, in 1956, are some of the earliest to be preserved in the archive. There are numerous references to the photographic tradition, and in particular to Rodchenko’s typical bird’s–eye views. Like a blank sheet, the snow was for Giuseppe Loy a virgin space where he could give free rein to his creativity.

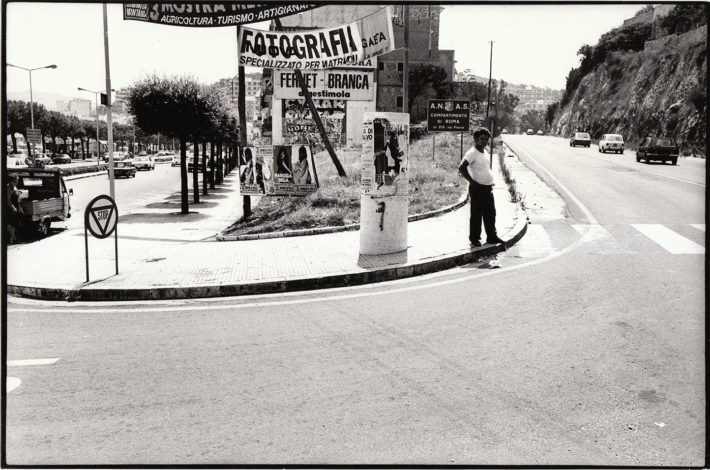

Campo de’ Fiori, Rome, 1960. Photo: Giuseppe Loy, © Archivio Giuseppe Loy.

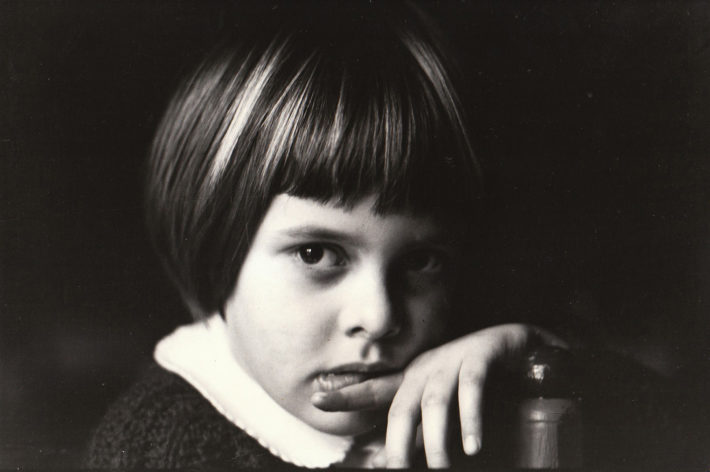

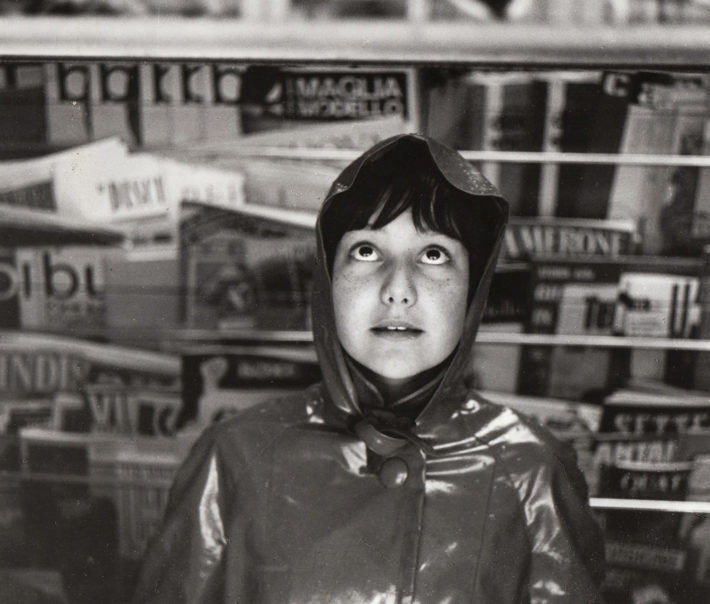

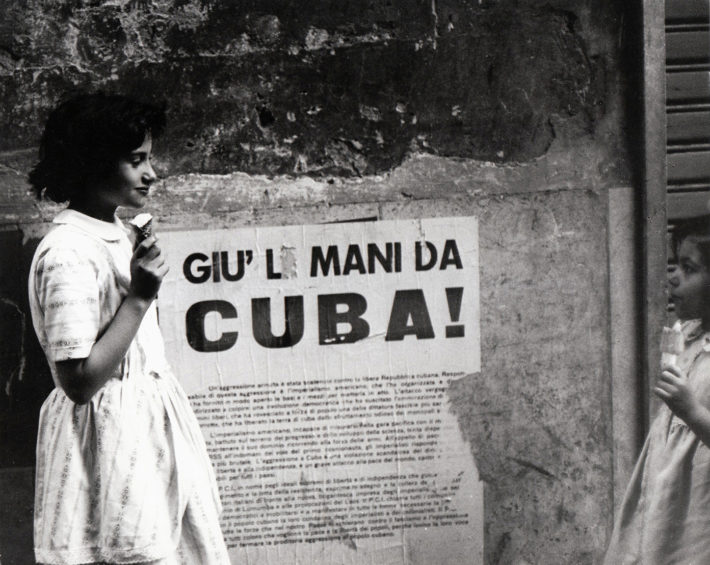

The pure pleasure he got from taking pictures did not prevent Giuseppe Loy, who was deeply committed politically, from using photography as a means of social inquiry. As a Communist, there was inevitable friction with the wealthy and deeply Catholic family of his wife; in the sixties he founded a cultural education center that set about supplying the libraries of small towns with books. Loy’s view of the social and economic changes of the sixties and seventies, and their repercussions in the Italy of the economic miracle, was not a neutral one. Loy’s lens, which he used to portray faithfully the Italy of his time, did not fail to notice the insistent presence of the advertising hoardings, the aesthetics of consumption that were redrawing the urban landscape in an increasingly intrusive fashion. Loy photographed semi-abandoned areas and major works of construction. Recurrent, among his emblematic subjects, asphalt roads on which the human presence is reduced to a minimum, often hardly more than a dot in compositions with strong contrasts of black and white and straight and curved lines; or the orbital of Rome, in 1960, and the broad avenues of the Tor di Quinto district. The attention he paid to the shifting landscape and the observation of places anticipated in some ways the research of the generation of photographers that has been defined as the Italian Landscape School,6 and in particular Luigi Ghirri, who with his friend Franco Guerzoni lost no opportunity to photograph, from a Fiat Cinquecento, the walls, ruins, scaffolding and buildings of the expanding suburbs of Modena.7 Never, though, did Loy’s political engagement get in the way of the immediacy of his vision, always free from compromise. An example is the photograph of two little girls eating an ice cream in front of a poster denouncing an episode in the Cuban crisis. A simple image, and yet one charged with meaning. Equally emblematic is the photograph of a woman taking water from a drinking fountain, in front of a wall on which are written the letters MSI, the initials of the far-right Italian Social Movement. The same vision can be found in the genuine and lively pictures Loy took of his children. Faces of happy and thoughtful kids who trustingly surrender to the camera and that today hang on the walls of the family’s house at Sperlonga, imparting gaiety and serenity to the setting.

Corso Francia, Rome, 1981. Photo: Giuseppe Loy, © Archivio Giuseppe Loy.

Loy must be given great credit for having been able to leave posterity a vivid and authentic record of the society in which he lived, without expressing a judgment; the Italy of its citizens and its artists, caught in the midst of little gestures. Minimal and fleeting, pregnant and sincere moments without affectation, they give an account of Italy in snippets, from north to south. Loy tells stories of famous people and passersby, of balls being kicked and box-office attendants at the movie theater, of children and families on vacation, against the background of a rapidly changing landscape. A simple Italy, but not a simplistic one, portrayed with elegance, without ever falling into the trap of the cliché. Loy’s is a photography that looks for minor aspects of reality, for it is in small things and small actions that the truth must be sought. He said so himself in one of the many poems he wrote and never published: “Beware of exultation, keep your joy brief and restrained, nurture serenity, cultivate at length the rational tranquility of the right conditions.”

Anna Loy, 1968. Photo: Giuseppe Loy, © Archivio Giuseppe Loy.

Gaeta, 1979. Photo: Giuseppe Loy, © Archivio Giuseppe Loy.

Sperlonga, 1976. Photo: Giuseppe Loy, © Archivio Giuseppe Loy.

Venice Biennale, 1966. Photo: Giuseppe Loy, © Archivio Giuseppe Loy.

Venice Biennale, 1966. Photo: Giuseppe Loy, © Archivio Giuseppe Loy.

Lucio Fontana in his studio, 1966. Photo: Giuseppe Loy, © Archivio Giuseppe Loy.

Alberto Burri in his studio, 1966. Photo: Giuseppe Loy, © Archivio Giuseppe Loy.

Ortisei, 1956. Photo: Giuseppe Loy, © Archivio Giuseppe Loy.

Civitavecchia port, 1960. Photo: Giuseppe Loy, © Archivio Giuseppe Loy.

Tor di Quinto, Rome, 1980. Photo: Giuseppe Loy, © Archivio Giuseppe Loy.

Tangenziale, Rome, 1960. Photo: Giuseppe Loy, © Archivio Giuseppe Loy.

Benedetta Loy, 1964. Photo: Giuseppe Loy, © Archivio Giuseppe Loy.

Piazza Navona, Rome, 1964. Photo: Giuseppe Loy, © Archivio Giuseppe Loy.

Rome, 1961. Photo: Giuseppe Loy, © Archivio Giuseppe Loy.

Naples, 1961. Photo: Giuseppe Loy, © Archivio Giuseppe Loy.

Alberto Burri, clay shooting range, Via Tiberina, Rome, 1966. Photo: Giuseppe Loy, © Archivio Giuseppe Loy.

Notes

1 Foto Magazin, 1/66 (1966), 29-31.

2 An exhibition of his photographs of Burri, Afro and Fontana entitled Questa è la tua lezione was staged at the Galleria Il Segno as part of the third International Photography Festival in Rome, curated by Marco Delogu, in 2004.

3 One of his pictures is on the cover of Luigi Paolo Finizio’s book Fontana e Burri, Un incontro senza incontri, published by Artemide in 2013, and nine more were published in Burri. Una vita by Piero Palumbo, brought out by Electa in 2007.

4 Obiettivi su Burri. Fotografie e fotoritratti di Alberto Burri dal 1954 al 1993, Fondazione Palazzo Albizzini Collezione Burri, Città di Castello, March 12-September 12, 2019, curated by Bruno Corà.

5 Rosalind Krauss et al., Art since 1900: Modernism, Antimodernism, Postmodernism (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2005), 411-14.

6 Roberta Valtorta, Luogo e identità nella fotografia italiana contemporanea (Turin: Einaudi, 2013), XVII.

7 Franco Guerzoni, Nessun luogo. Da nessuna parte. Viaggi randagi con Luigi Ghirri (Milan: Skira, 2014).