15 March 2019

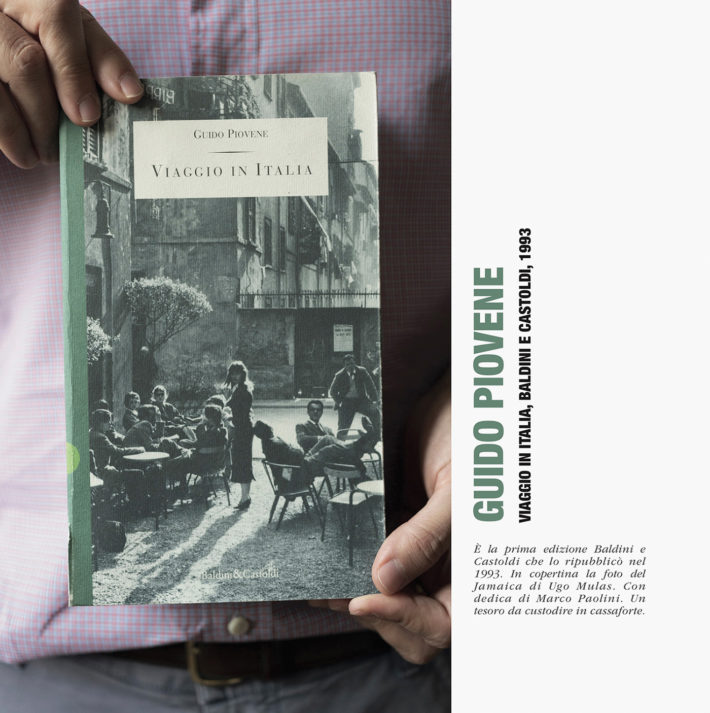

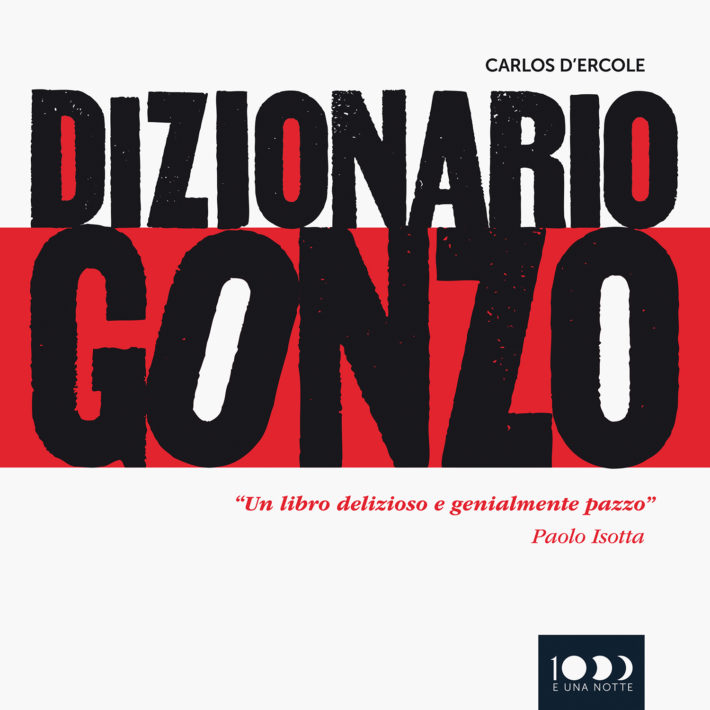

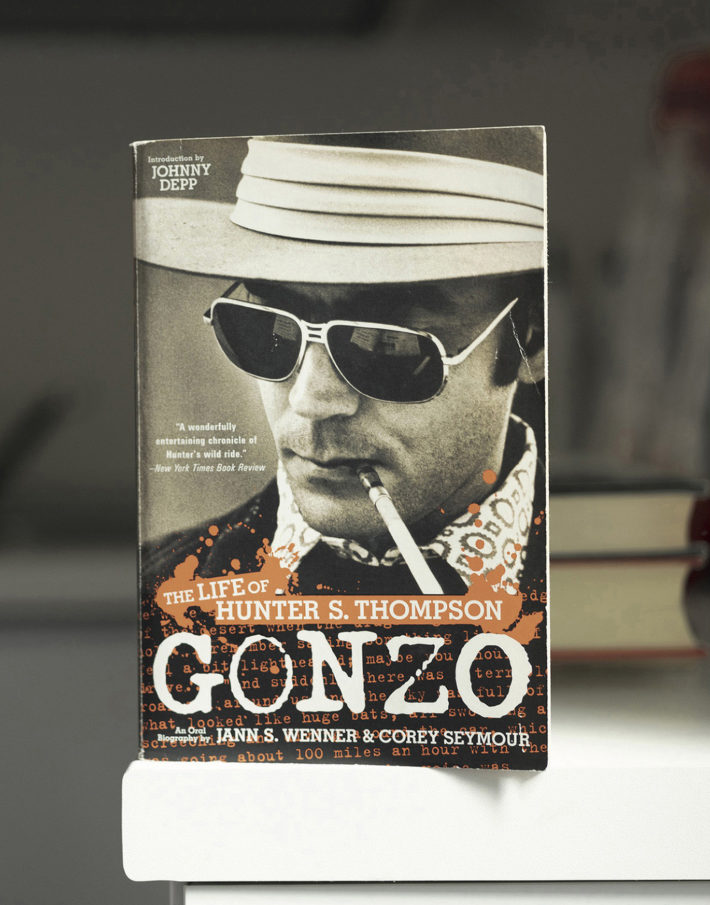

It doesn’t happen very often that you come across a book as unpredictable, curious and vibrant as Carlos D’Ercole’s Dizionario Gonzo. It is brought out by 1000 e una notte, a small Milanese publisher. The title is an explicit reference to Hunter S. Thompson, undisputed master of gonzo journalism, and is in itself an invitation to pick the book up and read it. The cover, designed by Robert Saywitz, reflects its spirit. It’s a hard work to classify. There are categories into which it could be pigeonholed—dictionary of sentiments, memoir, travel book, autobiography, catalogue of the author’s literary passions—but none of them is capable of capturing the unique character of a piece of writing that takes a perspective all of its own, with no fixed routes and boundaries. The protagonists of this Dizionario are undoubtedly the books Carlos D’Ercole has loved, but other important players are the cities, places, memories and anecdotes of an intense life filled with meetings, friendships and discoveries. Everything flows with total freedom, there is never any hint of his turning a blind eye, taking an ideological stand or sticking to any rule other than the simple spontaneous and enthusiastic acceptance of the ideas put forward in the volumes selected. Even the editions he chooses are never predictable.

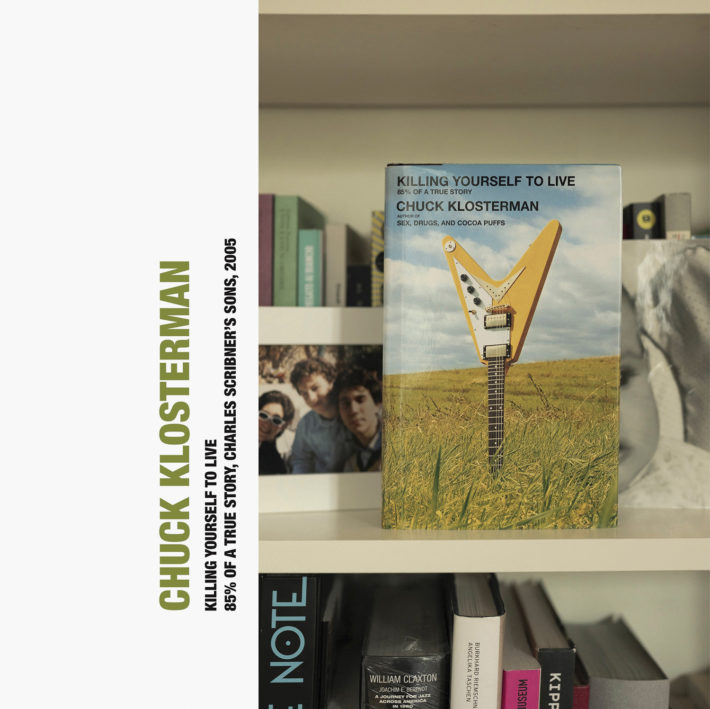

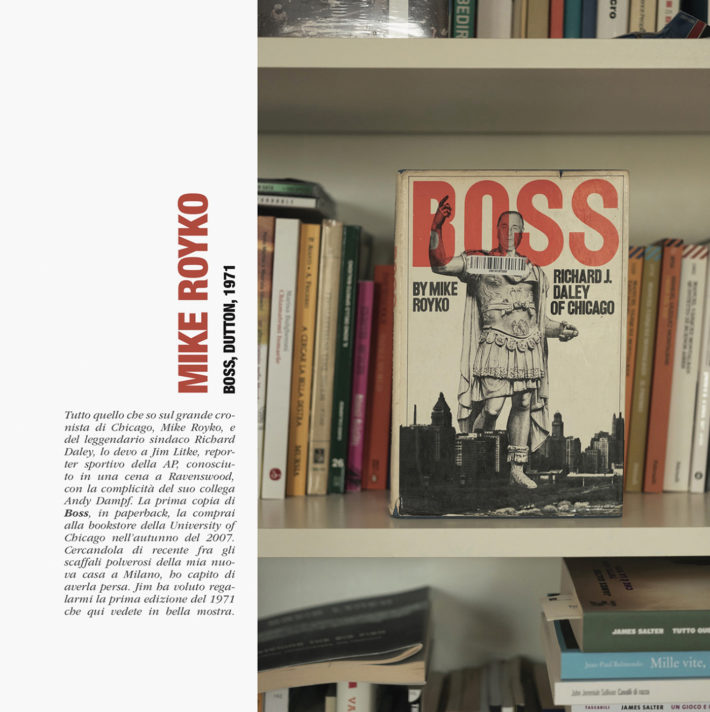

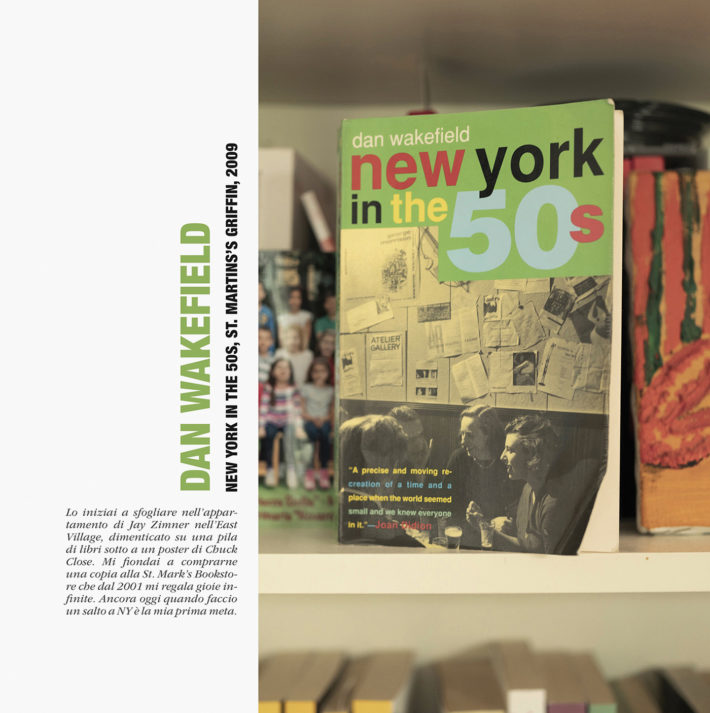

When he talks about Emmanuel Carrère’s Limonov he means a copy in French published in 2011 by POL (Paul Otchakovsky-Laurens) and bought “at Fnac in Monte Carlo, an oasis of pleasure in the Monegasque hell of the nouveaux riches.” In the entry on Obama the star becomes Mike Royko’s Boss: Richard J. Daley of Chicago, published by Dutton: “Everything I know about the great columnist from Chicago, Mike Royko, and the city’s legendary mayor Richard Daley, I owe to Jim Litke, sports reporter of the AP, whom I met at a dinner in Ravenswood, with the complicity of his colleague Andy Dampf. I bought my first copy of Boss, in paperback, at the University of Chicago bookstore in the fall of 2007. Looking for it recently on the dusty shelves of my new home in Milan, I realized I had lost it. Jim decided to give me the first edition of 1971 that has pride of place here.” And the reason why, at the beginning, we chose to call Dizionario Gonzo a curious book already becomes clearer here: because it is unusual, certainly, but above all because page after page it reveals Carlos D’Ercole’s insatiable curiosity about details, stories, nuances. On page 51 he lingers over Dan Wakefield’s New York in the 50s (St. Martin’s Griffin, 2009): “I started to leaf through it in Jay Zimner’s apartment in the East Village, where it lay forgotten on a pile of books under a poster by Chuck Close. I rushed off to buy a copy at St. Mark’s Bookstore, which has been affording me endless delights since 2001. Even now it’s the first place I go when I’m in New York.”

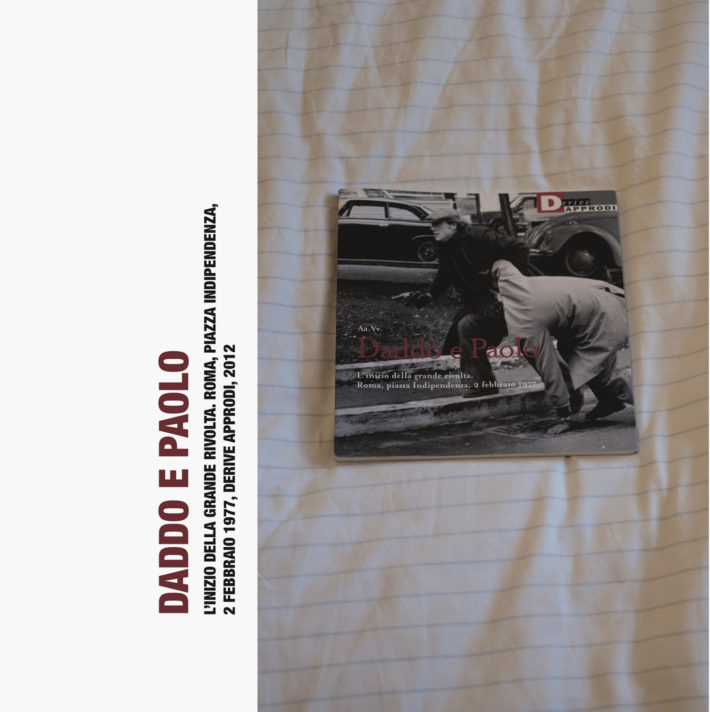

Speaking of revolt, the anni di piombo, political struggle and the famous photo that Tano D’Amico took of Daddo and Paolo in Piazza Indipendenza, Rome, on February 2, 1977, rediscovered on the cover of a volume published by Derive Approdi (2012), the author brings the chapter to a close by moving to the USA: “The book in my personal collection to which I’m most attached is Fugitive Days by Bill Ayers. In 2008, at the time of Obama’s first electoral campaign, Gretchen Helfrich, formerly a reporter for Chicago Public Radio, noticing my curiosity, introduced me to Bill Ayers, controversial founder of the Weather Underground who, his life in hiding at an end, was living in Hyde Park with his wife Bernardine Dohrn. It was a stimulating encounter, with some extraordinary anecdotes about Timothy Leary and the Black Panthers. He gave me a copy of the first American edition of Fugitive Days (Beacon Press, 2001) with a dedication. I must confess with sadness that I can no longer find it. Shame on me.” But vitality is perhaps the most striking aspect of this “disjointed homage to a jeunesse dorée which it is time to bid farewell”. The youth from which he must take his leave is of course his own, that of Carlos D’Ercole, born in 1978, lawyer, collector, author of Vita sconnessa di Enzo Cucchi (Quodlibet, 2011) and the man behind the publishing operation that a few years ago brought the first and only Italian translation of Albert Spaggiari’s Les égouts du paradis into the bookstores (Le fogne del paradiso, Oaks, 2016), the extraordinary account of the “heist of the century” pulled off at the Société Générale in Nice in July 1976. A masterstroke planned and executed by the daring Albert Spaggiari, an adventurer sui generis who after fighting with the French army in Indochina and working for the Organisation armée secrète (OAS), carried out his robbery on the Côte d’Azur “sans arme, ni haine, ni violence” (“without arms, without hatred, without violence”).

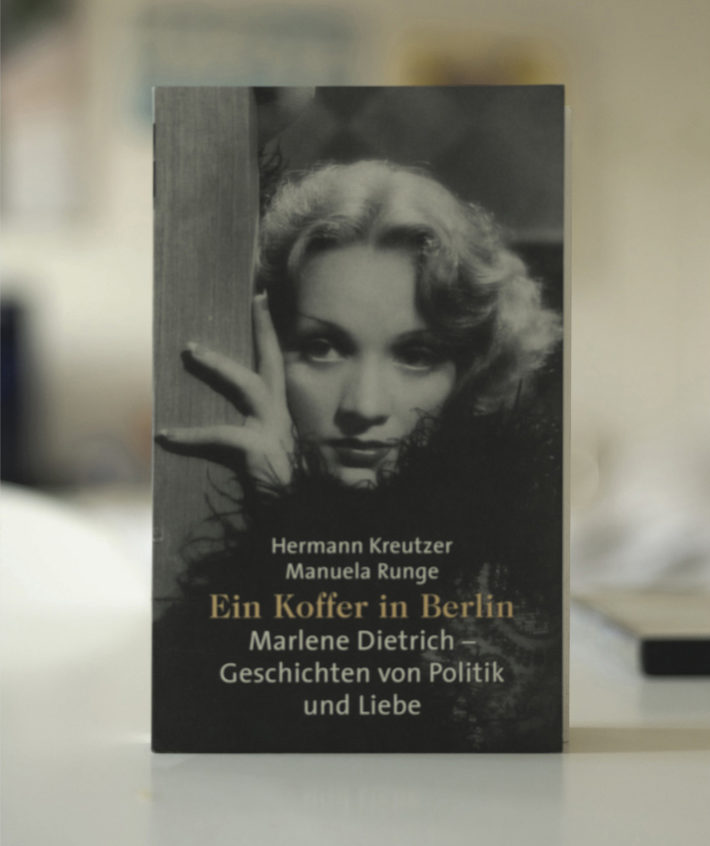

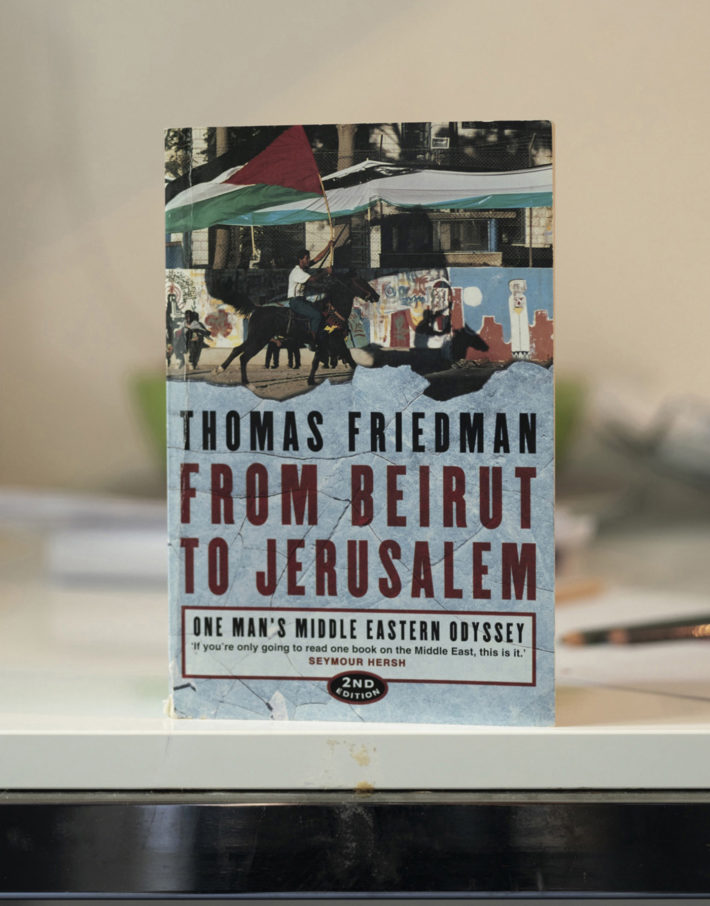

It is the sense of adventure that gives the Dizionario its pace, an electric current that runs from books to the cities Carlos D’Ercole has known and loved: Rome, Milan, New York, Chicago, Madrid, London, Paris, Berlin, Buenos Aires, Moscow, Beirut. His discovery of Thomas L. Friedman’s From Beirut to Jerusalem (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1989) was made in the Lebanese capital, at night: “Who says that nightclubbing can’t reveal books that are unknown to us? At three o’clock in the morning on the terrace of the Sky Bar, epicenter of Beirut’s high society, the American girlfriend of my Armenian host asked me how much I knew about the history of Lebanon. ‘Not much’, I replied, getting to grips with my third Moscow Mule. ‘Then you should read Thomas Friedman.’ I have to say that she was very persuasive.” A few pages earlier, the author focuses on Hermann Kreutzer and Manuela Runge’s Ein Koffer in Berlin (Aufbau, 2001), and notes: “It was a gift from Leonie von Rhade on the day of my departure from Berlin. My suitcase was already full of books plundered from Dussmann, that temple of bibliophiles whose only rivals are perhaps Foyles in London and El Ateneo in Buenos Aires.” Then he returns to the East Berlin of 2003, “where everything was within reach, ridiculously low rents, abandoned apartments that in the space of a few days were turned into galleries, disused stores in which theatrical happenings were cobbled together at 3 in the morning, the Chemical Brothers at Cookies, Russendisko evenings at the Kaffee Burger organized by Wladimir Kaminer, Ani DiFranco in a deconsecrated church, Terry Richardson at KaDeWe, retro nights at the Club der Republik, in what was once a government building of the DDR.” On page 39 there is even space for Ben Harper, “involuntary procurer of other musical discoveries: his slide guitar on “Flake” introduced me to Jack Johnson, who in turn brought me to G Love’s “Rodeo Clowns” and then to Donavon Frankenreiter’s “Free.” I recall a concert by this harmonious trio in Central Park in the summer of 2004. I have proof of it in a photo that has resurfaced from oblivion in which I was immortalized with Jack at Strawberry Fields a few hours before the concert.” Flickering memories of a youth barely over, not yet tinged with nostalgia. The atmosphere is always one of celebration, even when he turns his attention to the Italian edition of the collection of conversations with E.M. Cioran, Un apolide metafisico: “For the vulgate of cultural and philosophical journalism Cioran is the nihilist par excellence, the stateless man obsessed with death. Nothing could be more false. I have reread the translation of his interviews published by Adelphi. This is not pessimism, it’s an injection of vitality.” Voilà.