15 May 2020

When you write you can follow a plan or you can stray every so often from the thread of the story, in order to bring onto the page things picked up from who knows where. A bit like when we step away from ourselves, from familiar situations, from the places we are most fond of. Chiara Barzini is the second kind of writer. Even this interview entailed a dipping in and out of the conversation: from Facetime to a video call on WhatsApp to voice alone. The connection kept getting interrupted, a series of gaps to slip into to catch our breath between “Can you hear me?” and “Yes, I can hear you.” All writers have a center where they concentrate their storytelling energy and Barzini’s center lies in places. Places to come in and out of, places that get muddled up and shed light on her characters: from the house in the country where she is sitting out the quarantine to more remote locations, from those of her childhood or imaginary ones to those of her writing and of the loss of self. A tour that starts from Umbria, passes through Alicudi, Topanga Canyon, Santa Cruz, Rome, and ends in Los Angeles, the setting of her book Things That Happened Before the Earthquake (Doubleday, 2017), which is in the process of being adapted for screen by Oscar-winning director Robert Zemeckis.

There are some people who can’t wait to get out of the house and others who would be happy to stay there until September. How has this period been for you?

Here we’ve had snow, a windstorm, we lost the phone signal and internet connection. I’ve been attacked by a pack of sheepdogs when I was out for a walk and had to hide by climbing up a tree. While strolling at dawn, I’ve seen three roe deer, a fox and a rainbow. Having access to all this has been like being admitted to the most spectacular of all VIP rooms. Even the local hunters are going around with their eyes filled with wonder.

Are you still writing?

I think most of the things that I’m writing in this period are just a ruse to keep myself sane, like everyone else. But in this atmosphere of “standstill,” incredibly, I’m able to focus on projects that go deeper, requiring time and care, and which have no prospect of an immediate or guaranteed result. I am trying to treat this exceptional situation as an opportunity to work on a novel on a continuous basis. I’m paying very little attention to the news and trying to read authors who were writing when this natural order of things held sway around them.

Topanga Canyon, Los Angeles County, California, 2020.

A natural order in which you seem at ease.

I’m happy to be able to live this moment, a bit like a mother who is happy when her child is taking a very long nap and she thinks “how nice, afterward he’s going to be in a good mood and everything will be better.” The feeling is that we are discovering what we like most and what belongs to us most as a species in this new world. Being able to listen to your own thoughts is a true luxury.

No downside?

Of course there is. Now that we’re living in the countryside arguments break out when the wind blows from the north. We say terrible things, and then we take them back when the weather improves. It’s not that being surrounded by nature necessarily means living an idyll, but there is certainly a measure of honesty and a chance to get to the core of matters we had forgotten about.

Seeing that we are under house arrest, let’s talk a bit about your places. On your Instagram profile there are many photos of places, in the country, at the seaside, surreal monasteries. In your fiction locations seem crucial. They modify the characters, influence them.

You’ve hit on my obsession. For me it’s very important to access places I’m fond of, places that have helped to change the way I perceive the world. Nature locations, but also the opposite. Chaotic cities, that sense of oppression which I have come to recognize as something familiar. Especially in America, having lived in places that were far from glam.

Such as?

In Los Angeles I lived in the San Fernando Valley. In a neighborhood with wide boulevards like the ones you see in Magnolia, residential and commercial: shopping centers, carwashes, laundromats, fast-food joints. For me it was absurd, going back there years later, to realize that I had missed it. Walking past a fast-food joint, I was hit by a strong whiff of fried oil and my heart melted.

Are you nostalgic?

Sometimes. There are obsessions to which I often return. For instance, doing research into the geological and historical aspects of some places.

Topanga Canyon, Los Angeles County, California, 2020.

Research in what sense?

I’ll give you an example. Los Angeles, which is once again going to be at the center of my next book, has undergone huge changes since the time when the first Spanish colonists arrived, and it goes on changing. I’m interested in finding out about the relationships and conflicts that developed between the Europeans and the Native Americans and their land, their places, the wilderness. From the second half of the 19th century onward, the Californian grizzly—a subspecies of the grizzly bear—was the target of ruthless hunting, and this eventually resulted in its extinction. After this, it became the symbol on the flag of California. I’ve read marvelous accounts of the death of the last Californian grizzly, shot in 1922.

Rome and Los Angeles, your cities, are in a way wild places, not too civilized, chaotic and violent. Like your countryside. Untamed, childish places, where a state prior to the rule of law holds sway. Almost like the Garden of Eden.

It’s great this thing. I don’t really know where this attachment comes from. I grew up in rural surroundings. If I see a drinking trough for animals in the middle of a field I feel at home. When you’re a child, your relationship with nature is amplified. In every city I’ve lived in I’ve always gone looking for that natural side, which for me is redemptive. In Rome I lived in the countryside, in a barn outside the city. In Los Angeles I had the solace of Topanga Canyon, which later became a place of safety. When I went to university it was in Santa Cruz. I lived in a forest with very tall sequoias. There were old-time hippies still living in log cabins.

In Italy, apart from Rome? I noticed that among your photos there are pictures of an island filled with children that looks like Neverland.

In Italy there is Sicily, Alicudi in particular, where I used to go when I was small and try to go back to when I can, but it’s difficult because there are no roads. There are a lot of steps and the children try to persuade me to carry them on my shoulders. I got to know Alicudi when I was young thanks to an uncle who had done up a ruin there. In the evening he would read us fairytales on the terrace and anything seemed possible. He told us stories of the women of the island who at the end of the 19th century used to take ergot, which had a psychedelic effect. They said that they could fly, but that island is a place which has an intrinsic psychedelia, even without the help of ergot. The people I met there are part of me and have become like a sort of family. Very deep ties of affection that remain even when don’t see each other for years. It is certainly the place where I’ve experienced the strongest and most vivid emotions of my life.

Traveling with Luca Infascelli, Wyoming, 2010.

On the subject of wild places, I’ve read that that in the Hills of Los Angeles there are pumas running free.

Yes!

We’ve seen a lot of animals returning to the city in these days. Dolphins in Venice, hares in Milan.

When all this is over the animals will go away. No more dolphins, no more hares. It’s a pity.

You like the idea of nature gaining the upper hand?

I’m always amazed when nature worms its way forcefully between cracks in the concrete, when fig trees burst out of tuff walls, when volcanic scoria is able to carve itself a way down the mountain. I like to see creepers winding around the dead branches of the Christmas trees we leave on the terraces in the winter, creating new trees made of ivy.

Surrendering to nature.

This is what I’ve loved most about Sicily and California: the fact of always having to reckon with an untamed nature. It’s like surrendering to the famous higher power all those 12-step programs speak of. The natural order of things, the one sought by Virginia Woolf, is exactly what we are experiencing in this moment. It gives me a great sense of relief. It’s a power, like faith, something bigger than us, to be humbly respected. We have to place ourselves at its service: without competitiveness, without any pressure to perform.

We needed a pause from the frenzied lifestyle that we had before?

I still haven’t understood how we got to expect so much from ourselves. There’s a poem by Mariangela Gualtieri that reflects on this: “I’m telling you this / we needed to stop. / We knew. We all felt it / that it was too furious, / our frenzy. Being inside of things. / Outside of our selves. / Squeeze every hour—make it yield.” Nature has extraordinary strength. Think of volcanoes. In Italy we are lucky to have access to such powerful geological formations. We are not even aware of it, but we are blessed by entire cities scattered around the feet of explosive mountains, with thousands of people living their lives in this way. I think that it’s in part due to this atavistic coexistence with nature that we are able to treat this moment with so much respect.

Do you often find yourself in tune with the places you live in?

It happens. Not as much as I would like, owing to my lifestyle. In the city not much, but it only takes something small to find it again: a ray of light passing through branches and falling to earth, the smell of the woods early in the morning, even in a city park. I try to go back to the places that can generate that kind of feeling.

Traveling with Luca Infascelli, Arizona, 2010.

Does that kind of thing prompt you to write?

I write stories about things that catch my imagination. Certainly, it’s when I’m in a state of peace, in which I feel I can trust my thoughts, that I’m able to find the right energy to start writing.

How do you feel at home?

Always a bit restless. Especially if the weather’s good outside. I always feel guilty toward my children. I’d like to do more adventurous things with them. For my brother and I, childhood was an adventure. Our father gave us this great gift when we were young, and I’d like to do the same for them. Then there are the moments in which I’m writing and am concentrated, with the blank wall in front of me and a cup herb tea gone cold, twirling and pulling my hair into little balls and leaving them on the corner of the desk. In those moments the house becomes a monastery with a few pockets of neurosis.

A bare house. I was imagining you in a house full of plants.

I have a terribly black thumb. Barbara Alberti, who lives in my neighborhood, has lent me a study where I go to write. Her husband Amedeo has an incredibly green thumb. He talks to the plants, chats with them. He’s grown a forest of bamboo. I’ve spent months with them, and I’ve always tried to understand how he does it: he touches a plant and it turns green, luxuriant.

What’s your relationship with magic? Los Angeles is going through a spiritual boom: Gwyneth Paltrow’s Goop, moon milk, tarot cards.

We have seen an out-and-out commercialization of spirituality in recent years. If you haven’t tried ayahuasca at least five times, if you haven’t had Tantric sex or had your tarot cards read by the guru of the stars you’ve understood nothing of life. Goop is the epitome of this. It is selling something which you ought to arrive at by instinct, on your own account.

With effort, too. Not by buying leggings with planets on them to do yoga in.

But now, at the same time, New Age spirituality is part of pop and mainstream culture. In any case, it’s something that comes out of the desire to break away, to feel better about ourselves.

What do you like in a house? Objects that you love, amulets?

Books. There’s a corridor of books that I take with me on my various moves.

Chiara Barzini at the home of the writer Lauren Mechling during the presentation tour for Things That Happened Before the Earthquake, Brooklyn, New York City, 2017.

How do you treat books? Do you underline things and dog-ear the pages or are they immaculate?

I underline, fold the corners down, scribble in the margins. I like to go back and read my notes again.

The most underlined?

An anthology called Writing Los Angeles, edited by David L. Ulin, it’s a collection of the best and strangest things written about Los Angeles, from the end of the 19th century to the beginning of the 21st.

Other objects?

An altar by the bed with holy pictures and lots of Madonnas of every sort and size. Many amulets, lucky charms found in the street, my great grandmother’s old rings, rosaries of a certain color that make me feel calm. Miniatures. Candles, lignum vitae.

Are there places that you’re afraid of?

No. There are places where I don’t like to be. Crowded situations where everyone is distracted and there’s no energy going round. I find it depressing to be with other people without communicating, without exchanging anything. When I find myself in those situations, I can feel estranged. A lot of people criticize me for this. They tell me “Where’s your head at? You’re spacing out.”

I’m looking at your picture on WhatsApp as we speak, the one of you holding your son in your arms. It looks like a painting of the Madonna and Child. You have an absent look here too.

I’m there and I’m not there. It’s a struggle. Sometimes I don’t have my feet on the ground. I waste time, I lose the thread of things.

When you space out what do you think about?

It’s always just impulses, sensations, never whole flights of fancy. They are fixed images. My son is like me. He’s seven years old and he does the same. He drives me crazy.

Pity that I’ve missed seeing Chiara floating in the hyperuranian realm in the flesh. Is there a writer that has inspired you for the way she or he feels, thinks and writes about places?

Virginia Woolf, who had such an intense relationship with nature. Joan Didion, who has written essays on watercourses, on earthquakes, storms, fires and winds. And Christopher Isherwood, a true romantic despite his ironic and detached English style, who wrote about the desert of Death Valley in his diary: “A desert is a great empty picture frame, and we can’t resist using it for a portrait of our private disaster.” Setting our feelings against a wild backdrop ennobles them and perhaps makes us feel a little less afraid.

Chiara Barzini with her daughter Anita and friend Julia Meyer, Topanga Canyon, Los Angeles County, California, 2017.

Chiara Barzini (middle) with friends, Topanga Canyon, Los Angeles County, California, 2017.

Chiara Barzini with her friend, the writer and political activist Kate Schatz, Santa Cruz, California, 2017.

Chiara Barzini on a journey, Utah, 2010.

Grand Canyon, Arizona, 2010.

Topanga Canyon, Los Angeles County, California, 2020.

Geese at night, Campagnano di Roma, Rome, 2013.

Topanga Canyon, Los Angeles County, California, 2020.

Her children Sebastiano and Anita during the lockdown at Castiglione in Teverina, Viterbo, 2020.

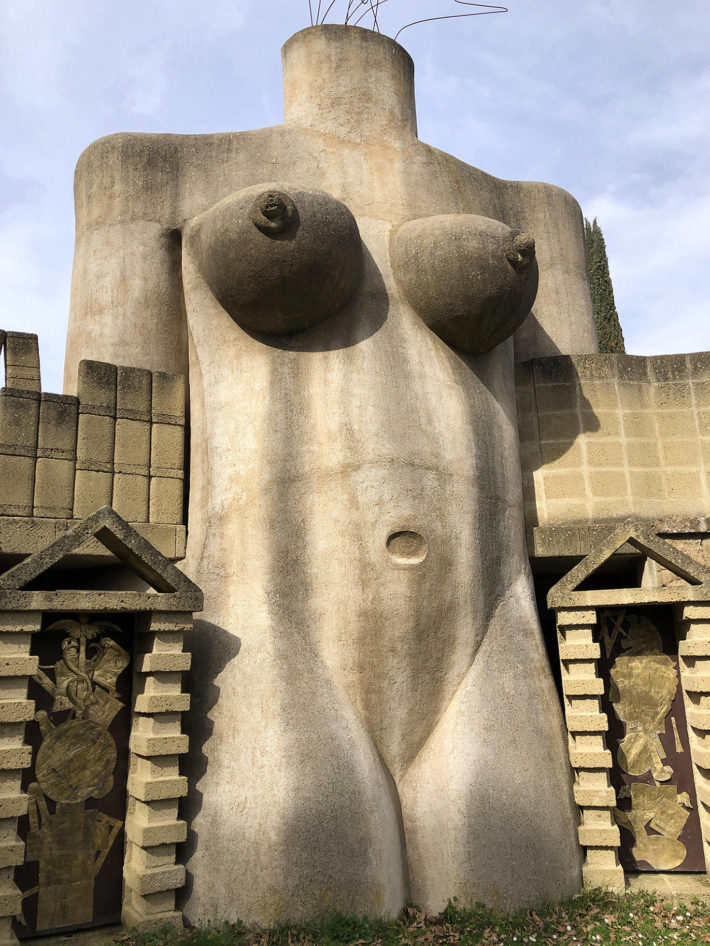

The statue of the Great Mother, La Scarzuola, Montegabbione, 2020.