30 May 2019

Carlo Mollino was already fifty-eight old when his friend the surveyor Felice Garelli made him an unusual proposal: to dismantle the Taleuc barn that he owned at Champoluc, a wooden rascard dating from 1664, used as a storehouse and barn in the Val d’Ayas, in the Aosta Valley region, and move it to the opposite side of the valley, behind the church of Sant’Anna, in order to turn it into a vacation home. The undertaking is the focus of a recent study,1 Carlo Mollino. L’arte di costruire in montagna. Casa Garelli, Champoluc, published by Electa, by two experts on Mollino, the researcher Laura Milan and Sergio Pace, a professor at Turin Polytechnic and editor among other things of Carlo Mollino architetto, 1905-1973, also published by Electa (2006). Following in the family tradition—his beloved and autocratic father was the famous Eugenio, an engineer and successful property speculator from Voghera, proprietor of a thriving engineering firm with which he had constructed entire districts of Turin—Mollino was a master of design: he taught Architectural Composition at Turin Polytechnic and was able to marry the maximum of rigor with the liveliest creativity. He was an eclectic genius, and a solitary one. A lover of the mountains, he was an enthusiast for off-piste skiing and via ferrata climbing at high altitude and had been a theorist of downhill racing, to which he devoted a unique treatise.2 And he was also an original photographer, expert on aerodynamics and stunt flyer. A connoisseur and lover of women, and especially women’s bodies—in his eyes, the quintessence of beauty—he loved to dress them up and photograph them in the oddest poses: from the side, from behind, with bare feet, from the front, with the groin wedged into the back of a chair, with the innocent look of a schoolgirl or the tormented one of a lascivious virago, immortalizing them in thousands of Polaroids that constitute a boundless stock of female charms.3

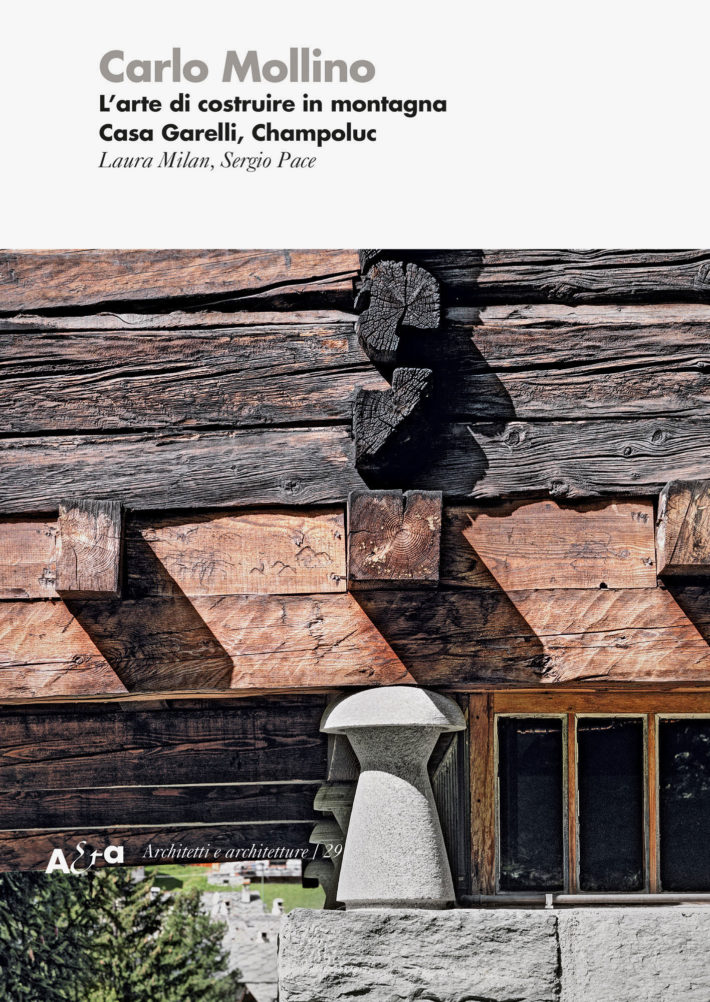

Cover. Detail showing the stone cladding and a stone boléro, the original wood of the 17th-century rascard and the new wood of Mollino’s intervention. Photo: © Marcello Mariana.

Decades prior to his involvement in the Casa Garelli project, in 1937, Mollino had already demonstrated his talent by designing the new headquarters of the Società Ippica Torinese, on the corner between Corso Massimo d’Azeglio and Corso Dante: a building suspended in time and space, an architectural monument of the 20th century that broke the deadlock in functionalist rationalism with its prodigious solutions, but that was demolished in a fit of madness in 1960 to make room for the celebrations of the Unification of Italy. With Aldo Morbelli he had designed the interiors of the RAI Auditorium (1952), and together with Mario Federico Roggero the condominium on Viale Conte Crotti in Aosta (1951-53). As for Alpine architecture, right after the war he had built the ski lodge of the Slittovia di Lago Nero at Sauze d’Oulx (1946-47), restored at the beginning of the 21st century by Giovanni Brino and Giorgio Raineri: “one of the most three-dimensional buildings in modern Italian architecture,” the historian Kidder Smith would call it,4 in which the structure of a light aircraft coexists with the form of a ghost ship. And he had already constructed the Casa del Sole at Cervinia (1947-55), along with the Fürggen cableway station (1950-53), designed by him but later extensively altered without his consent by the engineer Dino Lora Totino. In the years 1952-54 he also produced two more designs for houses in the mountains: Casa K2 for the entrepreneur Luigi Cattaneo, on the Agra plateau, and Casa Capriata, above Gressoney-Saint-Jean, completed posthumously in 2014. And with the furnishings for Casa Miller and for the homes of his friends (Minola, Devalle, Orengo), as well as for Attilio Lutrario’s dance hall (1960), Mollino had reinvented the architecture of interiors, designing tables, chairs, beds, chaises longues, armchairs, cabinets and escritoires. His furniture, often one-off pieces or produced in limited runs, has over time become valuable collector’s items. They are sculptures in motion, the effect of biomorphic suggestions: locust-chairs, gazelle-armchairs, butterfly-lamps. Anatomical details like the rib cage of a heron, the thighbones of a deer, the branches of a stag’s antlers or the vertebrae of a whale provided the inspiration for the legs of a table, the back of an armchair or the line of a desk.

North front. Photo: © Marcello Mariana.

After all these experiences, the challenge proposed by his friend Garelli, surveyor, builder and producer of cement-based materials who had bought the rascard at Champoluc in the summer of 1962 for 850,000 lire, represented for Mollino an opportunity to consolidate a relationship and to experiment: “I have in no way forgotten what I promised you: it is a job that suits me and that I feel like doing, and not just out of friendship. I think I will soon be able to give you everything at once: these little works need to be met head-on.”5 In reality it was a task of some complexity. Mollino reproduced the old stone base on which stood an upper volume of wood, with an overhang of about two meters on two opposite sides. In a historical and architectural peculiarity, the two structures are separated by a gap, an empty space, in which are set ten 50-cm-high mushrooms of gray granite (boléri in the patois of the Aosta Valley), made up of a tsapé, a cap, and a pi, i.e. a foot or stem, held on the stone base by concrete poured into a hollow girder that in turn rests on the top of the wall. The saddle roof covered with slate tiles tops the building at a height of five and a half meters. The rascard, a construction typical of some parts of the Aosta Valley region, was used to store wheat and other cereals. To prevent the entry of rodents and the rise of damp from the bare ground to the granary above, it did not stand directly on the stone, but on those mushroom-shaped granite pillars that, having lost their original function, were retained by Mollino as a structural and stylistic element: an almost apotropaic gesture, perhaps made ironically or simply in order to evoke the labor of the farmers who lived in those austere valleys. Anyway, Mollino chose to run a narrow and continuous wooden window all the way round the perimeter of the pillars, an Alpine reinterpretation of a strip window that owed a great deal, according to the authors, to the openings in the living room of the Haus am Horn, the prototype dwelling built for the exhibition at Walter Gropius’s Bauhaus in 1923.6 Thus, between 1963 and 1965, Mollino appropriated a relic of the popular architecture of the Aosta Valley and reinvented it in his own fashion, reconciling past and present, tradition and innovation. Like a bricoleur, he dismantled Garelli’s hut and reassembled it on the other side of the valley, adding a new base, along with a stone staircase to provide access, a large door for the passage of cars and another for people on foot and a series of tall and narrow windows, with stone sills and metal gratings that have a square section. At first, he had considered using reinforced concrete, but ended up turning to natural stone instead. For the outside stairs he resorted to thick planks of larch and invented a springboard structure made up of a concrete beam with thirteen wooden treads that rest on two continuous metal profiles, while the handrail, made of white metal tubing, is anchored to the beam at four points. The result was futuristic: “It looks like the ladder of a spaceship ready to take on passengers for a journey in time,” write Laura Milan and Sergio Pace.7

View of the balcony facing north. Photo: © Marcello Mariana.

Inside, the grid defined by the boléri dictates the layout of the walls, almost all of them load-bearing, and the arrangement of the various spaces. Here the genius of Mollino, who had been given the job of turning a 17th-century barn into a vacation home for the 20th century, the age of mass tourism, is revealed in full. He laid out the space on three floors, organized around a central service core that houses the staircase (built of stone at the base and of wood on the upper floor), the corridors and a light well through which pass part of the wiring and plumbing and the chimney flue. It is the backbone of the whole chalet, a completely new addition to the existing rascard. On the ground floor, Mollino installed a Thun stove that feeds a warm-air heating system and constitutes a very chic fitting with its cladding of green terracotta tiles decorated in relief; tiles which reappear on the ground floor of the light well and on the upper floors, interrupting the wooden covering of the walls. On the ground floor there is also a small garage, a space for use by the domestic staff and the so-called tampa, the Piedmontese name that he gave to it on his plans, i.e. an informal den or meeting place for the family and their guests. Climbing to the second floor, beyond the entrance and a small bathroom, we find a kitchen, a dining room and a living room, facing onto the village and the massif of Monte Rosa, while on the third floor is the sleeping area, with four bedrooms and two bathrooms. In short the reconstruction of Garelli’s chalet was a tour de force that reflected an obsessive attention to detail. Mollino designed for instance the shutters of the small and large door on the ground floor: he had them made of wood, with elements in aluminum alloy, fixed in turn with wrought-iron nails. And wrought iron was used again for the internal and external handles. Finally, at Champoluc just as at Cervinia for the Casa del Sole, Mollino designed all the wooden furniture: bunk beds, bedside tables with shelves, chairs. The authors of this study deserve credit for having accurately identified, through research in the archives, not just the construction materials, like larch and stone from Luserna and Malanaggio, but also all the craftsmen and firms that contributed to the execution of Mollino’s design, such as the carpenter Luigi Tesio and the Silvio Costa company that supplied the Tapiflex flooring of the kitchen.

Detail of the interlocking logs (Blockbau) at the corner. Photo: © Marcello Mariana.

When the work was complete, Felice Garelli was so pleased with it that he asked Mollino to carry out an intervention in the family tomb at San Genuario, in the province of Vercelli. “I enclose a photo of the ‘rascard’ and am waiting to hear from you a date when it would be possible for you to make a trip up there to see the finished work. We are all satisfied, but we would be happier to hear your opinion,” he wrote on July 27, 1969.8 Then, at the end of 1971, he turned to his architect friend again for two garages adjoining the chalet: “For a construction of this kind there is no need to bother someone like Mollino, but after much reflection I am afraid of doing something jarring and so I would prefer a little plan from you. Will you do it for me?”9 In June 1972, Mollino would deliver a sheet of tracing paper to him with a detailed plan for a square structure to house two cars, but it would never be built. These were extremely busy years for him. He was at grips with the design of the Chamber of Commerce, a suspended glass prism, and with the reconstruction of Turin’s Teatro Regio, for which he had thought of the form of a woman’s bust, with the interior all rounded, like an egg. A man of great originality, Mollino adhered scrupulously to the rules of the architectural discipline while redefining them with daring and the greatest expressive freedom. He had method, culture and imagination. He made innovations while conserving and conserved while innovating. The story of the Garelli rascard, a relic brought back to life and given a new mission, is a demonstration of this: like a magician, Mollino succeeded in bringing past and present together, even if only in fragments. For all those who have set themselves the goal of reconciling experimentation with respect for archaic architecture, his lesson remains a model.

View from the northeast. Photo: © Marcello Mariana.

East front. Photo: © Marcello Mariana.

South front with the external staircase. Photo: © Marcello Mariana.

Detail of the balconies facing west. Photo: © Marcello Mariana.

Details of the external staircase with a springboard structure made of a reinforced-concrete beam with a variable cross section, thirteen wooden treads resting on two continuous metal strips and handrails of white metal tubing. Photo: © Marcello Mariana.

The dining room with the chairs designed by Mollino on the model of the ones for the Casa del Sole at Cervinia. Photo: © Marcello Mariana.

Details of the external staircase. Photo: © Marcello Mariana.

Details of the external staircase. Photo: © Marcello Mariana.

Detail of the boléro, a 50-centimeter-high granite “mushroom.” Photo: © Marcello Mariana.

Details of the strip window that runs around the perimeter of the base. Photo: © Marcello Mariana.

Main entrance to the second floor from the corridor of internal circulation. Photo: © Marcello Mariana.

Detail of the interior with the terracotta-tile decoration and the original telephone. Photo: © Marcello Mariana.

The wooden staircase on the second floor leading to the bedrooms on the upper floor. Photo: © Marcello Mariana.

Corridor of circulation on the third floor. Photo: © Marcello Mariana.

View of a bedroom with the furniture made to Mollino’s design. Photo: © Marcello Mariana.

View of a bedroom with the furniture made to Mollino’s design. Photo: © Marcello Mariana.

Thun stove clad in ceramic tiles on the ground floor and the stone staircase that leads to the second floor. Photo: © Marcello Mariana.

Thun stove clad in ceramic tiles on the ground floor and the stone staircase that leads to the second floor. Photo: © Marcello Mariana.

The living room on the ground floor is illuminated by the strip windows, through which the “mushrooms” are visible. Photo: © Marcello Mariana.

Notes

1 Laura Milan and Sergio Pace, Carlo Mollino. L’arte di costruire in montagna. Casa Garelli, Champoluc (Milan: Mondadori Electa, 2018).

2 Carlo Mollino, Introduzione al discesismo (Rome: Casa Editrice Mediterranea, 1950), republished as an anastatic reprint with essays by Mario Cotelli and Massimiliano Savorra (Milan: Mondadori Electa, 2009).

3 See Fulvio Ferrari and Napoleone Ferrari, eds., Carlo Mollino: With Naked Eye: Photographs 1934-1973 (Florence: Alinari, 2009); Fulvio Ferrari and Napoleone Ferrari, eds., Polaroids by Carlo Mollino (Bologna: Damiani Editore, 2014); Francesco Zanot, ed., Carlo Mollino: Photographs 1934-1973 (Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2018), catalogue of the exhibition L’occhio magico di Carlo Mollino: Fotografie 1934-1973 at CAMERA-Centro Italiano per la Fotografia, Turin, January 18-May 13, 2018.

4 G.E. Kidder Smith, The New Architecture of Europe: an illustrated guidebook and appraisal (Cleveland, OH: World Publishing Company, 1961), 180.

5 Letter from Carlo Mollino to Felice Garelli, November 20, 1964, private archives of the Crovella Garelli family, quoted in Milan and Pace, Carlo Mollino. L’arte di costruire in montagna, 6.

6 Milan and Pace, Carlo Mollino. L’arte di costruire in Montagna, 12.

7 Ibidem, 11.

8 Ibidem, 28.

9 Ibidem.