12 December 2018

Over the ten years that he was artistic director of the Richard Ginori company, from 1923 to 1933, Gio Ponti, the most versatile Italian architect and designer of the 20th century, created three hundred and fifty decorations and two hundred models for the historic ceramics manufactory at Doccia.1 They were magnificent objects, of peerless elegance, often one-off pieces of great sophistication and at the same time extreme simplicity. Many of them are now on display at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris in a major retrospective, Tutto Ponti, Gio Ponti archi-designer, curated by Sophie Bouilhet-Dumas, Dominique Forest and Salvatore Licitra, that for the first time pays homage to every aspect of the creativity of this eclectic genius of Italian architecture and design, through innumerable examples of its infinite manifestations. In fact the exhibition in Paris comprises not just vases, ceramics, sketches and paintings, but also lamps, tables and other pieces of furniture, plans of the Italian-style houses he designed and their furnishings, created over sixty years of activity, as well as notebooks, his beautiful travel diaries and the drawings he made for Il Corriere della Sera to illustrate the hundred or so articles he wrote for the Milan-based newspaper.2 There are also a large number of objects designed for craftsmen and industrialists of distinction, such as Christofle, Venini, Fontana Arte, Cassina, Singer & Sons and Altamira: handles, candlesticks, fabrics, flatware, dinner services, theatrical costumes, sanitary fixtures, chandeliers, tiles, frames, chairs, armchairs and coffee tables. These have been borrowed for the exhibition from a series of archives like those of the Fundación Anala y Armando Planchart, Palazzo Bo and Palazzo Liviano and from private collections like that of Antonella Fiorucci, which has at the last moment lent a walnut and brass console table made by the craftsman Paolo De Poli. Thus over sixty lenders, sponsors like Molteni and Richard Ginori, the involvement of forty odd scholars and institutions and the exemplary display design by Jean-Michel Wilmotte, with the collaboration of Italo Lupi, have made it possible to reconstruct the entire course of Gio Ponti’s artistic and creative career from the twenties until the end of the seventies.

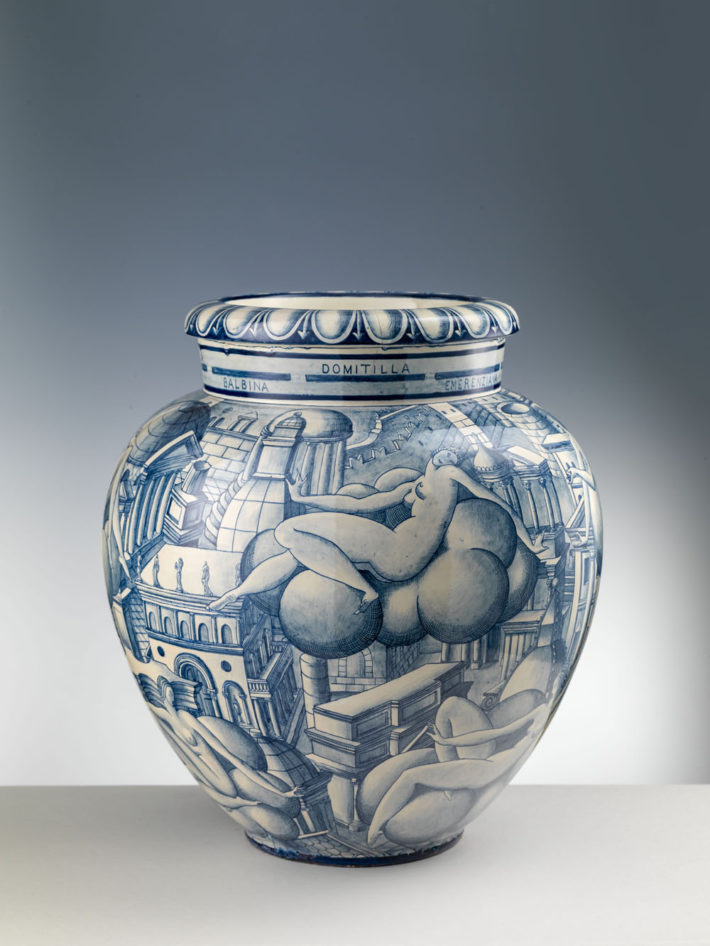

Donne su nubi (“Women on Clouds”), majolica vase painted monochrome blue, 1924-25, Gio Ponti for Richard Ginori, Doccia. © Museo Richard Ginori della Manifattura di Doccia, Sesto Fiorentino, Polo Museale della Toscana.

The first object to catch our attention is a majolica vase from 1924-25, entitled Donne su nubi and decorated in blue and white with the rounded forms of a series of naked women reclining on clouds, while around the neck ancient Roman names, Domitilla, Emerenziana, Apollonia and Balbina, evoke obscure martyrs of the early Christian period. The fact is that, having been hired by Richard Ginori in 1923 through the good offices of the family of his wife Giulia Vimercati, Gio Ponti from the outset chose to revisit traditional motifs, ranging from archeology to architecture. He did this not so much to pay tribute to masters of the past like Vitruvius, Serlio and, Palladio, and still less to play the erudite game of citation, but to create a new style, a modern style that would give his forms a unique, recognizable and “Italian” identity, and ensure that his products had a competitive edge on the market. In 1924, taking part in the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts, the first world’s fair to be held after the war, staged at the Esplanade des Invalides in Paris, Gio Ponti won the special jury prize for ceramics with Cista (The Classic Conversation). Here we see the magnificent urn of white Doccia porcelain adorned with stylized drawings alternating with geometric lines and gilded decorations in relief made with an agate stylus in the shape of kneeling angels, while a classicizing muse leaning on a column serves as the grip to lift the lid. This reappraisal of classical art to suit an ultra-contemporary taste was hailed in the Paris of the twenties: the capital of culture was eager to break with the past by inventing new, freer and more flowing forms in all the fields of art, from dance to painting, from music to architecture, while paying great tribute to the tradition of the past. Ponti’s porcelains have simple and smooth forms that lend themselves perfectly to decoration, as with orcino vase Prospettica, the other celebrated Ginori vase in the shape of a wine jar and made of blue, white and yellow porcelain, in which the lines of the squares follow the curve of the vessel in a geometric design that repeats itself endlessly, with each one housing a different motif, a capital, a column, a circle or an arch, a cylinder, a spire or a stela, representing the constituent elements not only of Italian taste, but of Italian civilization.

La passeggiata archeologica (“An Archeological Stroll”), white porcelain with gold decorations, 1925-27, Gio Ponti for Richard Ginori, Doccia. © Museo Richard Ginori della Manifattura di Doccia, Sesto Fiorentino, Polo Museale della Toscana.

So the Milanese architect, who graduated from the city’s polytechnic, made his debut as an artist. And in any case he liked to describe himself as “an artist who fell in love with architecture.”3 But an artist extremely attentive to the interaction between industry and craftsmanship, as is evident from another exhibit at the MAD, Labirinto, a piece of silk fabric that was painted and partially embroidered with gold thread in 1928-30 by the artisans of the school at Cernobbio, patronized by Carla Visconti di Modrone. “Industry is the ‘mode of expression’ of the 20th century, it is its way of being creative. In the combination of art and industry, art is a category, industry is a condition […],” wrote Ponti on the occasion of the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts held in Paris in 1925.4 “To understand what is modern, we should look in exhibitions only at things that actually belong to the market, that accompany our lives as part of our everyday clothing and environment.”5 From ceramics to pieces of furniture is but a short step. After his success at the Paris Expo, where his vases sold like hot cakes, to the point where he had to replenish the entire stock for the Monza Biennale, he set up a venture with Tony Bouilhet, the young proprietor of Christofle who had met him in Paris and immediately been won over by the style of this elegant and genial Italian. Their friendship was to last for over half a century. Ponti would come up with new models for the celebrated Parisian company, like the Flèche: presented at the Venice Biennale in 1928, it is a candelabrum formed from two cornucopias joined together in a sort of embrace around an arrow, a symbol of the marriage between his niece Carla Borletti and Bouilhet. Ponti would design the one and only house he built in France, at Garches on the outskirts of Paris, for the couple. Baptized l’Ange volant, the “Flying Angel,” it is a perfect example of the Italian neo-Palladian style of living, reproducing the mix of modernity and classicism he had developed for Richard Ginori. With Luigi Fontana, who wanted to diversify his production of glass and panels, Ponti started to design small decorative objects like mirrors with ornamental motifs and lamps. This would lead to the birth of Fontana Arte, a quality brand still in operation today. Thanks to the exhibition in Paris, therefore, we can rediscover the extremely contemporary character of a lamp designed almost ninety years fa, like Bilia (1931), a simple globe of light set on an upturned cone, or the 0024, launched in 1933 and still right up to date with its cylinder of light ringed by twelve glass discs.

Bilia lamp, 1931, Gio Ponti for Fontana Arte, Milan. © Gio Ponti Archives, Milan.

A member of the board of governors of the Monza Trade Fair, Ponti set up the Labirinto group (a name suggested by Ugo Ojetti), which included Carla Visconti di Modrone, the mother of Luchino Visconti, Pietro Chiesa, Paolo Venini, Tommaso Buzzi and Emilio Lancia, his partner in the Milanese studio of architectural design from which the Domus Nova collective would spring. The result of the group’s lively dynamics would be a range of furniture, split into four categories for different parts of the house: bedroom, lounge, dining room, office. Thanks to an agreement with the Borletti family, owners of La Rinascente, this furniture would be put on sale at moderate prices in department stores as well. For Domus Nova’s first collection, Ponti chose to build his furniture out of ash, one of the cheapest kinds of wood, and at the MAD you can see the tables, bedroom suites, shelves divided into compartments, wall-mounted bedside tables and backlit cabinets that were mass-produced and used years later by Ponti himself as furnishings for hotel rooms. At the end of the twenties, the new idea in interior decoration, founded as it was on an urgent need for education, was a very simple one: the new Milanese middle class had to be taught to free itself from the antique, to get rid of the gloomy and imposing Art Nouveau pieces of the old dining-room suites, with their bosses, horseshoes and Renaissance gratings, and open up to the new taste, which did not simply mean repudiating the antique, but combining antique furniture with modern pieces.

Thus from objects of everyday use the focus shifts to tableware, and from tableware to furniture and from there to interior decoration. The exhibition in Paris covers the whole of the creative and professional journey that took Gio Ponti from ceramics to furniture design, from furniture to the design of houses, and from there to public buildings, such as the School of Mathematics at La Sapienza University in Rome. A gem of Fascist architectural rationalism that was commissioned in 1932 and built in 1935 under the supervision of Marcello Piacentini, it has a horseshoe-shaped plan and distinct blocks: the rectangular building for the school, the library and the common room of the professors and the two curved wings of the fan-shaped building housing the amphitheaters. And then the office buildings, like those of the Montecatini group in Milan: a complex made up of several blocks built at different times and located between Via della Moscova (1935-38) and Largo Donegani (1947-52), whose fronts were clad in horizontal slabs of marble, leading Curzio Malaparte to celebrate it as “a building of water and leaves.”6 And the Ferrania, building on Corso Matteotti, the headquarters of the EIAR (later RAI) on Corso Sempione and the building on Piazza San Babila. In all of these he renounced a subdivision of the spaces in order to ensure the maximum of flexibility. And then there was Palazzo Liviano in Padua, which looks like something out of one of de Chirico’s Metaphysical pictures and is still considered the most beautiful university building in the world, as a result of the perfect union between Ponti’s spaces and Campigli’s frescoes. Next we come to the Italian Institute of Culture in Stockholm, a design that is still striking today for its extraordinary anticipation of developments in taste, and to skyscrapers like the Pirelli, where sixty years ago Ponti’s genius found solutions that appear futuristic even for contemporary starchitects. And again, to cathedrals like that of Taranto, to mention just the most beautiful and unfortunate one, whose lacy façade is reproduced in the panel at the entrance to the exhibition at the MAD.

House at Via Randaccio 9, Milan, 1924-26, designed by Gio Ponti and Emilio Lancia. © Gio Ponti Archives, Milan.

Pride of place of Ponti’s many houses goes to the one on the corner of Via Domenichino and Via Monte Rosa in Milan’s Trade Fair district, with its double window on the corner that amplifies the view outside for anyone seated in the living room. And its pieces of walnut furniture with their light lines, slightly arched feet and graining ending in metal ornaments. There is the house on Via Randaccio, “architecture after architecture,”7 use Ponti’s own description of what would be his first act of design after finishing his academic training at Milan Polytechnic. “My father was a one-off: a modern old-time architect,”8 said his daughter Lisa. And here too, as in the vases, as in the candelabra, as in the furniture, the antique was married to the modern in a love match, made by destiny, where the evocation of the Malcontenta and Palladio’s other villas in Veneto, which Ponti had studied in his youth, was combined with the boldest and most unexpected solutions of contemporary architecture, such as the open plan, the window wall, the elimination of corridors and the space that can be modulated with dividers and folding doors. Mallet Stevens had used an open plan for the French pavilion at the 1925 Expo and Ponti took up the idea to develop and rework it with his Italian touch and in keeping with a precise philosophy of living: “So-called ‘comfort’ in the Italian-style home does not lie solely in the fact that things answer to the necessities, needs and conveniences of our life and to the organization of services,” but is something more elevated “that consists in the full sense of the fine Italian term conforto,”9 declared Ponti in the first issue of the magazine Domus, the new publishing venture that he launched in January 1928. “The home accompanies our life, it is the ‘vessel’ of our good and bad moments, it is the time for our noblest thoughts; it should not be fashionable, because it should not go out of fashion.”10 And Ponti’s words accompany the visitor to this exhibition like the guiding thread of a labyrinthine route, full of deviations, eclectic in its desire to shift constantly from one field to another, and yet highly recognizable and always coherent, as it is inspired by a clear and essential and cardinal principle, and an extremely simple one in that it is the fruit of an ancient and fully assimilated wisdom: “Let’s go back to chair-chairs, house-houses, works without labels, without adjectives, to things as they should be, true, natural, simple and spontaneous.”11

Tutto Ponti, Gio Ponti archi-designer

Curated by Sophie Bouilhet-Dumas, Dominique Forest and Salvatore Licitra

Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris

October 19, 2018-February 10, 2019

Labirinto porcelain bowl, 1926, Gio Ponti for Richard Ginori, Doccia. © Museo Richard Ginori della Manifattura di Doccia, Sesto Fiorentino, Polo Museale della Toscana.

Aero teapot, 1957, Gio Ponti for Christofle, Paris. © Christofle Collection.

Flèche candelabrum, 1928, Gio Ponti for Christofle, Paris, Héritage Christofle. © Stéphane Garrigues.

D.153.1 armchair, structure in satin-finished brass, conceived by Gio Ponti in 1953 for his home on Via Dezza, in Milan, and brought out again by Molteni&C in 2012. © Molteni Museum.

Lobby of the Hotel Parco dei Principi, Sorrento, 1960-61, designed by Gio Ponti. © Gio Ponti Archives, Milan.

Villa Planchart, Caracas, 1953-57, designed by Gio Ponti. © Antoine Baralhé

Casa Laporte, Via Brin 12, Milan, 1936, interior, designed by Gio Ponti, Antonio Fornaroli and Eugenio Soncini. © Gio Ponti Archives, Milan.

Living room of Villa Arreaza, Caracas, designed by Gio Ponti, 1956. © Gio Ponti Archives, Milan.

Montecatini office buildings, between Via della Moscova (first building, on the left, 1935-38) and Largo Donegani (second building, on the right, 1947-52), designed by Gio Ponti, Antonio Fornaroli and Eugenio Soncini. © Gio Ponti Archives, Milan.

Palazzo Borletti, Via San Vittore 40-42, Milan, 1928, hallway, designed by Gio Ponti and Emilio Lancia. © Gio Ponti Archives, Milan.

Gio Ponti and his wife Giulia Vimercati, apartment at Via Dezza 49, Milan, 1957. © Gio Ponti Archives, Milan.

Living room of Villa Planchart, Caracas, 1953-57, designed by Gio Ponti. © Antoine Baralhé, Anala and Armando Planchart Foundation.

La mano della fattucchiera (“The Witch’s Hand”), porcelain hand-painted in gold and decorated with an agate stylus, 1935, Gio Ponti for Richard Ginori, Doccia. © Museo Richard Ginori della Manifattura di Doccia, Sesto Fiorentino, Polo Museale della Toscana.

699 Superleggera chair, ash wood and rattan, 1957, Gio Ponti for Cassina. © Cassina and Giorgio Casali.

0024 lamp, 1933, Gio Ponti for Fontana Arte, Milan. © Gio Ponti Archives, Milan.

Notes

1 Much of the production has been preserved in the Museo Richard Ginori of the manufactory at Doccia, which closed in 2014 and was acquired by the Italian state at the beginning of 2018. Its management was entrusted to the Ministry of the Cultural Heritage and Activities, which has recently assigned it to the Polo Museale della Toscana.

2 The articles, 130 of them to be exact, have been republished in the book Gio Ponti e il Corriere della Sera, 1930-1963, ed. Luca Molinari and Cecilia Rostagni (Milan: Fondazione Corriere della Sera/Rizzoli, 2011).

3 Alessandro Benetti, “Parigi omaggia Gio Ponti. Intervista a Salvatore Licitra,” Artribune (October 17, 2018).

4 Gio Ponti in “Le ceramiche,” in L’Italia alla Esposizione internazionale di arti decorative e industriali moderne (n.p., n.d, but Paris, 1925) 69. The text is cited by Giacinta Cavagna di Gualdana in “Les labyrinthes de Gio Ponti,” Gio Ponti. Archi-Designer, catalogue of the exhibition at the MAD (Paris, 2018), 53.

5 Ponti in “Le ceramiche,” 71. Cited by Cavagna di Gualdana, “Les labyrinthes de Gio Ponti,” 53.

6 Curzio Malaparte, “Un palazzo d’acqua e di foglie,” Aria d’Italia (May 1940). The text is cited by Sophie Bouilhet-Dumas in the catalogue of Gio Ponti. Archi-Designer, 74.

7 Gio Ponti, Amate l’architettura. L’architettura è un cristallo (Milan: Rizzoli, 2015), 53 (reprint of the Vitali and Ghianda edition of 1957). The text is cited by Bouilhet-Dumas in Gio Ponti. Archi-Designer, 42.

8 Related by Sophie Bouilhet-Dumas to the author of this article.

9 Gio Ponti in “La casa all’italiana,” Domus, no. 1 (January 1928), 7.

10 Gio Ponti, “La casa di moda,” Domus, no. 8 (August 1928), 11.

11 Gio Ponti, “Senza aggettivi,” Domus, no. 268 (March 1952), 1.