8 April 2020

Rudy Ricciotti lives in a house that follows the lie of the cliff, along the road leading out of Cassis, on a stretch of the coast in the South of France that is a long way away from les milliardaires of the Côte d’Azur. In front just the Mediterranean Sea, with scuba divers going out early in the morning with their equipment, and above a blue sky shining in silence that is reflected in the swimming pool surrounded by vegetation. “I didn’t do a renovation,” observes Ricciotti, “I designed the scenery.” The inspiration for this clearly comes from Curzio Malaparte, his great passion, who responded in this way to someone who admired his celebrated villa on Capri.1 He has chosen to live here and to work nearby, at Bandol, where everything is Mediterranean, Latin, Arab. And then we ask the architect born in Kouba, in Algeria, what languages are spoken in his Bandol studio. “Language can explain many things in the work of an architect. In my studio we mostly speak Latin languages, we have the accent of the South. Italian, Spanish, French. I speak Arabic too. My architecture, my life in general, pertains to a globalized idea of the Mediterranean.”

View of Rudy Ricciotti’s home in Cassis. Photo: © Archivio Rudy Ricciotti.

An architect and writer, he has been called a “polemicist” in France because of his determination to turn out one pamphlet after another, in short to make clear, and not just through buildings, his own vision of the world and his own dedication. “Do you know an architect capable of writing thirty books?” he asks, picking up some of his more recent titles to show us: L’exil de la beauté, the autobiographical Je te ressers un pastis? and Première ligne, a book of drawings that is a perfect reflection of his attitude toward the profession he has chosen. They are above all long interviews in which he elucidates a complex, irreverent, audacious way of thinking. “There’s a bit of Quentin Tarantino in me, don’t you think? I could be the Tarantino of architecture!” he declares, laughing and pointing his fingers like a pistol at the belly of his listener. “I’m very impulsive. We Mediterraneans are naïve, reckless, while the Parisians, the Anglo-Saxons, are afraid of everything. I have a certain mystical, metaphysical fear, but I’m not afraid of people.”

But what is the point of writing if your job is to construct buildings that will last for a thousand years and that anyone can see just by walking along the street? “I write to find out if I’m still alive. Writing is a stratagem that helps to communicate my neurosis very quickly. When people speak, they tell you straightaway who they are. After a few seconds you can tell whom you have in front of you. The word tells you everything. This is why I write and don’t stick to building. Writing has this ability to develop complexity, to explain it.” So materials, space, light and all the elements that architects utilize, and often manipulate, are not sufficient to convey the richness of a thought? “Certainly not. As an architect I feel that I’m a step behind authors, writers. If our architecture is so poor today it is because we do not have the capacity to bring out the true complexity of thought. I write so as not to lose my soul. It’s true, I prefer writing to designing.”

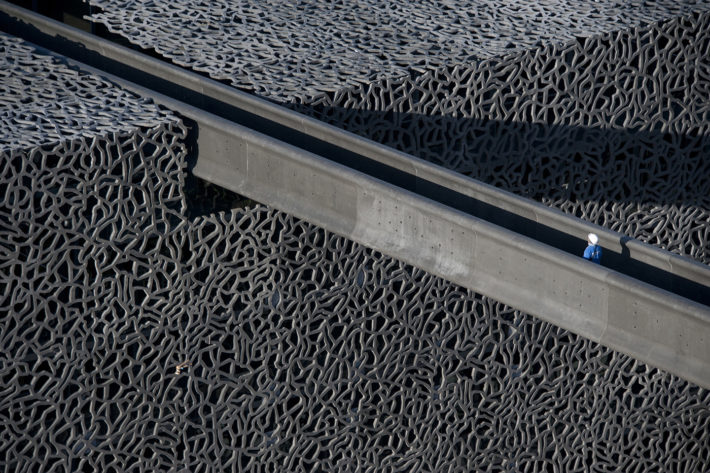

MuCEM, Musée des Civilisations de l’Europe et de la Méditerranée, Marseille, 2002. Photo: © Lisa Ricciotti.

Dozens of buildings under construction around the world, his signature on institutions created with the idea of bringing cultures together, like the MuCEM (Musée des Civilisations de l’Europe et de la Méditerranée) in Marseille, the Musée Jean Cocteau in Menton and the Pavilion of Islamic Arts at the Louvre, designed together with the Italian architect Mario Bellini. As well as bridges like the Pont de la République in Montpellier, supported by elegant and slender pillars of fiber-reinforced concrete, which unlike steel are able to look sinuous and sculptural and yet be very strong. Rudy Ricciotti, in fact, is the contemporary architect of concrete, preferably sourced locally, produced at a distance of less than twenty kilometers from the construction site. What he declares from the platform at all his lectures goes against every simplistic environmentalist position: concrete is the most environmentally friendly material there is on the planet. The point is not how it is used, but how it is produced. “I work with concrete because it is a local material. Concrete, in addition to furthering the interests of specialized workers and the preservation of artisanal knowhow, is the product of a short supply chain and above all is not speculative. Whereas oil and steel are: they are products that people use to play the market. Their value depends on factors that do not concern work, production and the use of the material. In the majority of cases, countries make all the concrete they consume, and it is often produced within a distance of twenty kilometers from the construction site. I know, what I’m saying is very different from the environmentalist moralism that pervades our age. I’m the only architect who says these things.”

This is what the thirty books he has written and the ones that are going to come in the future are for, to put across his ideas. For Rudy Ricciotti, architecture is a form of combat, a job for paranoiacs. A paranoia that you find hard to handle, to control when you are young. Indeed, that’s why architecture is a profession for the old. The creativity you have when you’re thirty is where the ideas come from, but it is the obsession and the awareness of your responsibilities that allows you to put them into effect. “I realized I was an architect at the age of 50, 55. It is difficult to be a true architect before that age. You’re young, you’re not able to condense in a project everything you’ve absorbed from life. Only with maturity does this become possible. It’s a complicated, fascinating, paranoid profession. It’s a struggle. I’m the coach of a team, I stay on the touchlines. I watch the battle with attention and I make small changes to the setup of my army. I adjust those things that can make a difference.”

Séverin Wunderman collection, Musée Jean Cocteau, Menton, 2007. Photo: © Olivier Amsellem.

It’s clear that, seated in front of this cliff overlooking the Mediterranean (“A scar on the planet that will never heal up,” he calls it), paranoia is a term that I’m not really able to grasp; at the very least you have to ask yourself how it is possible to wake up here, every morning, and feel any kind of anxiety or disquiet. But that is Rudy Ricciotti: he loves contrasts, discord. He is scrupulous and unpredictable, cautious and impulsive, cosmopolitan and a champion of local interests. The reason he goes to the studio every day at the age of 67 is “a question of responsibility and vitality: if you stop working, you start to smell the odor of death.” Responsibility means knowing that what you are building cannot admit errors, and we’re not talking of structural questions, for those there are the engineers. You can’t make mistakes because when you’re building you’re shaping reality. “You realize that it’s very dangerous to meddle in what surrounds you, to mold reality? In the first place you have to bear one thing clearly in mind: reality is not the truth. Truth and reality are different things. Architects have an important and delicate role, they have to be prudent, responsible and obsessive, they have to pay attention to every detail.” Does constructing a new reality mean influencing people, manipulating them? “It’s not a matter of changing people’s minds, of course. That’s not the point. But people establish a rapport with architecture and experience a corporeal, emotional, symbolic and even spiritual connection with that space. I cannot know what is going on inside the heads of those people, but I do know that the relationship that is established between architecture and its public can be very profound. This is why we need modesty, a lot of modesty in our work.”

And it is when Rudy Ricciotti pulls the word modesty out of his hat, or perhaps his holster, that we stop talking about aesthetics. We would like to find out at what point, in a project, someone starts to think about beauty, about the element that leads people to remember what they see, to photograph it, the element that makes the building memorable. “The question of aesthetics also stems from modesty, not from rules. There is no before and after, constructions are born out of an incessant exchange between culture, aesthetics and structure. There is no precise order. It is necessary to respect the sensibility and work of others, to analyze, listen, move with discretion. I always ask my assistants to read the competition notice carefully, to follow the guidelines with great precision. They take the first steps in the design process, and then I come in. I’m given all the information, the floor space, the functions, the heights, the land utilization, all the technical details, and from there on I intervene. I’m not the kind of architect who makes a sketch, a drawing, and then asks his assistant to do the work. No, it’s the exact opposite. I think that architects should stay in their place. Our job is to build, not to make architecture on paper. Build while taking into account the social, political and economic effects.”

Stadium, Vitrolles, 1990. Photo: © Serge Demailly.

Constructing, searching continually for “a beauty that today seems to have been forced into exile,” as he explains in his book L’exil de la beauté. Fight but always remain prudent. Does all this mean making compromises? He thinks for a long time before answering. He understands that we’re not talking about compromises with the local community, with politicians, with the client. “For me the defense of work, of the workforce is fundamental. The right to work, the one protected by the Italian Constitution. If I have to renounce one of my principles, I can only do so to defend the people who work on my constructions. The defense of work in the territory is my priority. I’m a patriotic architect who refuses to be colonized by ideas that are not mine. I think I’m the only architect who describes himself as a patriot.” Does patriot mean nationalist? “No, nationalism has nothing to do with it. The nationalist is someone who excludes, who rejects comparison, openness, competition. I take part in competitions all over the world, I have buildings under construction in Europe, North America, South America, everywhere. I’m certainly not a nationalist. Being patriotic, for me, means defending the work of every community you come into contact with. If I’m working in Brazil, I’m a Brazilian patriot. If I’m working in Italy, I’m an Italian patriot. You always need to have a strong connection with places, people, local cultures.” A connection that Rudy Ricciotti’s grandparents, who emigrated from Umbria to the South of France, knew all about, and that allowed them to grow. “We didn’t use the social elevator, we used the stairs,” and he repeats this three times. “The stairs, we took the stairs. And in architecture the same thing happens. We don’t need elevators, we have to work and climb one step after the other. It’s at work that the maximum importance should be placed on skills, on individuality. Without this idea, we will always be colonized. Here lies the difference between Anglo-Saxon and Latin architecture. Anglo-Saxon architecture consumes technology, while the Latin kind is mineral, basic, close to the ground, to the earth.”

And light, how much does it matter? “Ah, light. It’s too easy to respond: light is very important, obviously. Architects are very presumptuous when they say they work with light. Humility is needed. We do what we can, not what we would like to do. How can the architect work with light? It’s light that works with you. The architect is nothing in comparison with light. I work under the light, thanks to the force of light. Light is a physical phenomenon that has something mystical about it, and we shouldn’t mystify it. Do you understand that to get these concepts across I have to speak, I have to write, that it’s not enough for me to construct?” There have never been any masters at Cassis, or in the Bandol studio, and perhaps no pupils have come out of them either. “I love a lot of architects, but I have no masters. My points of reference are engineers, builders. I have a veneration for work. Working I’ve learnt to say ‘thank you’ and ‘please’ to those who realize my designs. And I don’t have pupils either, even if there are architects who think that I’m their master and I’m proud of them. They’ve passed through my studio and have gone on to have successful careers, but what makes me most proud is that none of them produces architecture ‘à la Ricciotti.’ I’ll never say that I’m a master, still less an artist. These things are ridiculous. I’m Rudy Ricciotti, and that’s already a lot.”

MuCEM, Musée des Civilisations de l’Europe et de la Méditerranée, Marseille, 2002. Photo: © Lisa Ricciotti.

MuCEM, Musée des Civilisations de l’Europe et de la Méditerranée, Marseille, 2002. Photo: © Lisa Ricciotti.

MuCEM, Musée des Civilisations de l’Europe et de la Méditerranée, Marseille, 2002. Photo: © Lisa Ricciotti.

Pont de la République, Montpellier, 2011. Photo: © Lisa Ricciotti.

Pont de la République, Montpellier, 2011. Photo: © Lisa Ricciotti.

Jean Bouin Stadium, Paris, 2007. Photo: © Olivier Amsellem.

19M, Chanel Métiers d’Art, Aubervilliers, Paris, 2020. Rendering: © Agence Rudy Ricciotti.

Arkéa Arena, Floirac, Bordeaux, 2013. Photo: © Philippe Caumes.

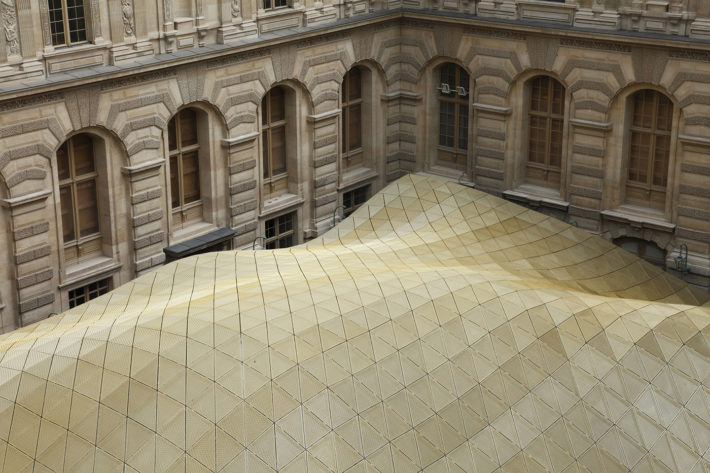

Département des Arts de l’Islam, Musée du Louvre, Paris, 2004. Photo: © Antoine Mongodin.

Jean Bouin Stadium, Paris, 2007. Photo: © Agence Rudy Ricciotti.

Jean Bouin Stadium, Paris, 2007. Photo: © Olivier Amsellem.

Rivesaltes Memorial, Rivesaltes, 2005. Photo: © Frédéric Hédelin.

Rivesaltes Memorial, Rivesaltes, 2005. Photo: © Frédéric Hédelin.

Rivesaltes Memorial, Rivesaltes, 2005. Photo: © Frédéric Hédelin.

Rivesaltes Memorial, Rivesaltes, 2005. Photo: © Frédéric Hédelin.

Centre Chorégraphique National, Aix en Provence, 1999. Photo: © Philippe Ruault.

Notes

1 Curzio Malaparte, La Pelle, Vallecchi Editore, Firenze, 1964, 289-290. English ed., The Skin, trans. David Moore (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1977), 203-05: […] I went to meet the German general and took him into my library. […] I accompanied him all over the house, going from room to room, from the library to the cellar, and when we returned to the vast hall with its great windows, which look out on to the most beautiful scenery in the world, I offered him a glass of Vesuvian wine from the vineyards of Pompeii. “Prosit!” he said, raising his glass, and he drained it at a single draught. Then, before leaving, he asked me whether I had bought my house as it stood or whether I had designed and built it myself. I replied—and it was not true—that I had bought the house as it stood. And with a sweeping gesture, indicating the sheer cliff of Matromania, the three gigantic rocks of the Faraglioni, the peninsula of Sorrento, the islands of the Sirens, the far-away blue coastline of Amalfi, and the golden sands of Paestum, shimmering in the distance, I said to him: “I designed the scenery.”