25 October 2018

The Milanese architect and designer Umberto Riva turned 90 on June 16 and a few days ago, on the occasion of the award of the Gold Medal for Italian Architecture for the 6th time, received a recognition for lifetime achievement. Part of his extraordinary body of work has recently been subjected to meticulous scrutiny by Gabriele Neri in the volume Umberto Riva. Interni e allestimenti (LetteraVentidue). The book, first published in the fall of 2017, has just returned to bookstores in a less expensive edition. Below you will find the lengthy introduction and a selection of the photos illustrating the text.

§

Preliminary Coordinates

Analyzing the long series of projects worked on by Umberto Riva over a career that has lasted almost sixty years, including urban development schemes, interventions of restoration, industrial design, housing, exhibition spaces, public buildings and much more, the design of internal space unquestionably stands out as one of his most original and fertile fields of investigation, one in which the multiple themes he tackled seem to converge and reinforce each other. A pupil of Franco Albini and Carlo Scarpa, but also an autodidact beguiled more by Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Pierre Chareau and Gaudí than by a modernism that was starting to be questioned in his university years,1 Riva has cultivated deeply that “middle ground” on which an exceptional part of the Italian architectural culture of the 20th century flourished. Like his teachers, in fact, it is in the architecture of interiors that he has found the perfect sphere for a curiosity that cuts across boundaries, attracted by the peremptoriness of the structures and the lightness of the detail, by the plasticity of the form and the possibilities of color, by the pure spatiality and the revelations of the light, by the craftsmanship of the work and by a certain vision of the living space.

This propensity was visible right from his earliest works, especially in the summer vacation homes, where Riva always reserved special attention—something not to be taken for granted—for the quality of the internal space, articulating it with respect to its container and to its natural or urban setting, but also working in a more self-referential manner on the architectural form and the figurative aspects. In a different way on each occasion: uninterested in the possibility of an a priori theoretical strategy, Riva has always taken a singular, empirical approach to design, aimed at questioning both the existing state of affairs and his personal fund of analytical and creative exercises carried out in the past. The basic premise from which his spaces start out is this: design is not a deductive process but something that begins with a prefiguration, with an intuition that has to be sifted through continual approximations, keeping a suspicious eye on one’s own work and the results achieved. In this sense his architecture stems, as his friend Giacomo Scarpini pointed out in the pages of Domus in 1969, from a decided “distrust in the starting point,” a distrust “of reality as it presents itself,” which has always prompted him to “go for the clean sheet in order to be able to initiate the operation of meaningful reconstruction of the object or the building on other bases.”2

However, a clean sheet does not mean turning one’s back on reality to take refuge in an abstract, ideal dimension, but the exact opposite: it involves tackling directly the conditions of the surroundings in a manner that is new each time, opening a difficult dialogue—which can turn into open opposition—with the aim of finding a way out of banality and toward a new expression of the everyday. So the counterpart to the reality evoked by Scarpini is a strong attachment to the world of the senses, understood as the dimension in which forms and colors are made manifest with the force of their concreteness, of their vividness, of their physicality: “[…] Certainly, I am not in favour of a mental kind of painting,” declared Riva twenty years ago, “just as I am not in favour of a mental architecture. I am for an architecture of things, a very physical kind, and for a painting with plenty of colour and a lot of form. So you see, I am absolutely not somebody who sublimates.”3

Between this heuristic disquiet and the need for concreteness of form moves his redesign of internal spaces, approached first of all by exercising the practice of drawing as a work tool and means of continual comparison. Regarding forms as a point of arrival and not of departure, Riva sees design as a process in which trial and error are indispensable allies in the effort to achieve a superior result. This is obvious when you look, in his archive of drawings, at the innumerable plans he made before arriving at a constructed solution. Riva has always insisted on the importance of this trial-and-error method, finding inspiration in the work of Scarpa: “From his drawings emerge the way he was never satisfied, his great figurative culture. He was really on a quest for the truth; he felt that there is a moral choice behind a need for a response, to give something meaning.”4 Because, on reflection, the act of design “is a continual circling of something that you know exists outside your will.”5

Display design of the exhibition Carlo Scarpa. Case e paesaggi 1972-1978, Palazzo Barbarano, Vicenza, 2000. The main hall. Photo: Paola De Pietri.

Partly for these reasons, Riva has never used his drawing—whose value had already been recognized in the eighties in a now historic quaderno di Lotus6—in a self-referential or ideological manner, as was stressed by Pierluigi Nicolin in reference to the period of Italian drawn architecture.7 Instead, we must add to its maieutic function the role of a rigorous means of communication, of an indispensable filter between the mind and the building site: an intermediate position, one of passage, that also determines its inevitable indefiniteness. The thin drafting paper that Riva had sent from Northern Europe was not in fact a canvas for conclusive and immutable visions but a temporary enclosure in which to pour all the possibilities received from the hand: everything would have to be falsified in the manner proposed by Popper, put to the test on the construction site in order to be superseded and in a sense nullified by its actual translation into material. Riva explains: “I have always given drawn architecture the value of a means, which only makes sense in its realization; in part because constructed architecture is loaded with a whole series of elements that are spurious, unforeseen, but give substance to the design.”8

Cover of Zodiac, no. 21, September 1972.

Given the importance of line in the elaboration of space, in order to present an overall picture of Riva’s architecture of interiors mention must also be made of his activity as a graphic designer and painter. The former was for him an early exercise in his years at university, when he used to create signs for stores and graphic designs of various kinds, something that he later refined into an indispensable ingredient of the project and a specialized field of work. Here we should cite his collaborations in the field of graphic design for publications: for example he renewed the layout of Superfici in 1961;9 for Zodiac10 he designed several original covers between 1969 and 1973; and earlier still he worked for student periodicals like Il Risorgimento.11 Even more profound, however, is his relationship with painting, which he considers a research akin to that of architecture and inevitably related to it that found a visible parallel in constructed spaces. In fact Riva’s first means of expression was on canvas, in the years immediately following the war, and he might have officially become a painter if it had not been for the personal events that led him, with much uncertainty, to take up architecture. (“I became an architect in spite of myself,”12 comments Riva, pointing to the many years it took him to graduate).

Although pushed into the background, his painting—commencing with the long series of pictures executed from the mid-seventies onward with crayons, oil-based chalks and India ink13—found precise parallels with his contemporary research into construction, representing a sort of underground river that often surfaced in the process of generating a plan, in the definition of a building’s form or in the importance given to the chromatic aspects of architecture. These last, in particular, are something that needs to be clearly borne in mind in the analysis of his interiors: fascinated by the ability of Matisse and Pierre Bonnard to use color to show “what we are lacking as architects: the beauty of the everyday,”14 as well as by the colorful compositions of Le Corbusier, Léger, Nicolas de Stael, Geer van Velde, de Kooning and Poliakoff, Riva has always assigned color a primary role in his designs, using it not just in a decorative manner but as an aesthetic means of emphasizing or creating particular situations.

Umberto Riva, E63 lamp, 1963.

Linked to color is the study of light: the Milanese architect has always paid a great deal of attention to illumination, both by weighing carefully the contribution of natural light and by personally designing lighting elements and fixtures. In his works we find windows of every shape and size, often in unusual positions as a consequence of a well-considered dialogue with the elements of the architecture; and obviously we also find the products of the activity as a designer on which he embarked in the sixties. His lamps—“illuminated glassware” he called them, sometimes inspired by the work of artists like Melotti or Brancusi—are part of a continual reflection on the possibilities of light in relation to space, even on a small scale.15 Different but complementary to this is the question of furniture design, a field which Riva had begun to explore in the fifties—when he was still a student—and which he later developed as an independent activity linked to industrial production but also connected with his architectural projects, although for these he has often preferred “classic” pieces (Thonet chairs, for instance) over his own.

Looking a bit more closely at the range of interiors designed by Riva, it is possible to discern some recurrent themes and figures. Since the mid-sixties, for example, the propensity to make use of broken lines, asymmetries, oblique angles and disjunctions between surfaces at the level of the plan has been an almost obsessive constant: a tendency that—as the architect has repeated on many occasions—derives from an aversion to the symmetrical and the static, from a magnetic attraction to unstable and precarious space, from the impossibility of closing and concluding the form. Distrustful of the fixed calm of the classical world, Riva has in fact always looked to Central European expressionism, with its rough and sharp angularity. It should be noted that, while indeed a constant feature of his work, the use and refinement of this geometric lexicon has not led to a mannered repetition, confirming the shifting and questioning nature of his vision. It was this modus operandi that allowed a Riva to maintain his personal independence and freedom of maneuver right through the second half of the 20th century, keeping a critical distance from all the isms of the period and putting himself in a position that critics of architecture have not been able to grasp fully.

Casa Berrini, Taino, 1967-68. Living room, with the concrete fireplace in the background. Photo: Giorgio Casali, Fondo Giorgio Casali, Archivio Progetti, IUAV University of Venice.

Emblematic too is his long and patient work on the detail, in which we can still see the influence of his teachers, but also the desire to go beyond their lesson through a continual redefinition of the real. This propensity is revealed in all sorts of inventions, and in particular in a perennial effort to recast some of the fundamental, archetypal elements of architectural space: the door, the window, the threshold, the table, the fireplace, the partition wall, etc. “I like to confer nobility on an interior,” explains Riva; “to make sure that no window, door or sequence is taken for granted. […] This is what nobility means to me: non-obviousness, care over detail, intelligent economy.”16

In this aspect too we can discern the lesson of Scarpa, who proved a revelation when he came into contact with him during his time at university in Venice: “I had been trained in the Milanese school of Albini and Gardella, so discovering Scarpa was pretty overwhelming. His figurative style was much more in my line. I’ve always thought the Milan school carried elegance too far, that it smacked too much of upper-middle class refinement. Scarpa taught me the intensity of architecture. And its suffering.”17 In the great Venetian architect Riva found the key to turning his impatience with the impossibility of formal perfection into a source of expressivity at the level of language:18 “His architecture is an x-ray of the process of formation of a possible, prospective but never complete image of form. Scarpa rejects simplicity, feeling the need to complicate everything, so that ‘the field’ of references is as wide as possible; in such a way that what ends up in the range of samples taken and finds made in figurative, technological and other fabrics has in itself the grounds for formal survival, without however being enclosed in the circularity of a form.”19 So the structural details of the Milanese architect often appear to be laden with a superimposition of signs—layered on the paper—that augment their molecular density, turning them into inventions that contribute to the definition of the space and not just to filling it: objects with “a very strong autonomous presence, halfway between the emblematic quality of a sculpture and that of a machine intended to perform a specific function.”20 And without lapsing into “Scarpism?,21 an insidious tendency that has afflicted many other professionals inspired in various ways by the work of the Venetian architect.

Fitting out of the entrance area of the Palazzo dell’Arte, Triennale, Milan, 1994-95. Photo: Francesco Radino.

The comparison with Scarpa opens up the complex question of the references that can be traced in Umberto Riva’s work. A thorough examination can in fact uncover in his designs innumerable figurative or other affinities with some of the great architects of the 20th century: Le Corbusier and Scarpa first of all, but also Kahn, Wright, Mackintosh, Chareau, Lewerentz, Schindler, etc. Sometimes these are explicit citations; in other cases, however, they are subtle, almost unconscious allusions. In general, though, such debts are made clear—even in the most obvious citations—after a process of personal rumination that produces completely new creations, of which the original reference is only in the memory.

The tension expressed by all these components—and by the many others that will emerge in the following pages—is also evident, in an exceptional manner, in the many displays for temporary exhibitions that Riva has designed since the sixties. Up until now, this has been a side of Riva’s work which has received incredibly little systematic study: apart from a few magazine reviews and the odd isolated contribution in the rare monographs on his work, these designs have never been given adequate exposure or analyzed methodically. In fact many of the photographs in this monograph have never been published before. And yet the evident quality of these displays prompts us to describe Riva as one of the few heirs and continuators of the exceptional museological tradition that stretched in Italy, almost without a break, from the Triennali of the thirties to the sixties, transforming on a large great and small scale the very conception of the museum.22 It is no coincidence that among the protagonists of the formal and epistemological revolution in Italian museology in the postwar years were some of Riva’s teachers, in whose work he was able to observe a new way of tackling the layout of an exhibition, the perception of the work of art, the relationship between container and content, the application of design to the support or display stand, etc.

Casa Righi, Milan, 2002-03. Living room. Photo: Andrea Martiradonna.

However, Riva’s museological conception also built on the contribution made by all those artists who have worked since the sixties on the interpretation of the exhibition space,23 and obviously drew on his own professional experience as well. Apart from a few minor episodes—such as the section at the Triennale in 1964 that he curated with Roberto Sambonet—his most interesting displays did not in fact begin to appear until the second half of the eighties, when Riva already had under his belt twenty-five years of architectural practice, substantial experience in the field of industrial design and long familiarity with the canvas. And moreover, the form that he is able to give to curatorial narration through his displays finds a precise match in the organic character of his domestic interiors, which present themselves not as a summation of elements but as a narrative capable of embracing every part of the design. By juxtaposing and integrating different levels—routes, structural elements, planimetric division and elevations, aspects of distribution, furnishing, finishes, color, lighting, etc.—Riva in fact creates, in homes as well as in exhibition halls, a complex system to which all the designed elements contribute: “my way of designing architecture stems from the assumption that all the parts must have an identity of their own; they must all come into play and therefore be in some measure necessary.”24

On close examination, behind this vision, which for Riva also harks back to the ability of architects like Borromini to orchestrate an interplay of references between all the parts of a whole, there are not just figurative motivations. The necessity of everything designed (or installed, or revealed) implies in fact the abolition of a hierarchical ordering of the architectural mise-en-scène, and thus a concerted dialogue in which all play a part. In this way, out of concrete and tangible phenomena, emerge some basic ethical principles—such as the rejection of any form of exclusion and a certain position of the human being with respect to architecture—that can be read between the lines in much of his work, and that perhaps have their origin in the social context in which he received his education as a man even before an architect, in the immediate postwar years.

With the priority given to this narrative, at times cinematic dimension,25 in order to understand the quality of Riva’s interior and display designs and the motivations behind them it is therefore necessary to look at them one by one, seeking to reconstruct the context, the starting conditions, the points of arrival and the substance. Thus one of the aims of these pages is to reorganize—in a manner that is not exhaustive but critical—these narrations, examining them in a series of thematic chapters that can help to connect up the plots of such a complex story.

Casa Insinga, Milan, 1987-89. View of the living room looking toward the fireplace. Photo: Francesco Radino.

Bar Sem, Milan, 1975-77. Detail of the sheet-metal volume for the coffee machine. Photo: Umberto Riva.

Display design of the exhibition Frederick Kiesler. Arte Architettura Ambiente at the Palazzo dell’Arte, Triennale, Milan, 1996. The central space with the work Goya. Photo: Giovanni Chiaramonte.

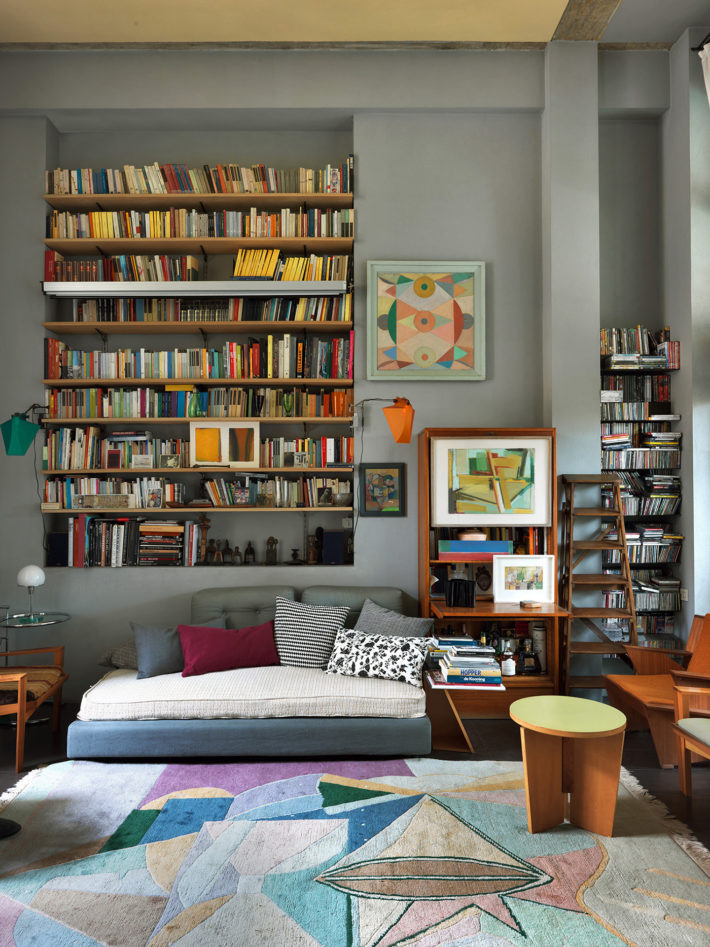

Casa Mieli Ballerini, Milan, 2004. Living room with the bookcase. Photo: Andrea Martiradonna.

Renovation of the Caffè Pedrocchi, Padua, 1994-98. Gallery adjoining the Sala Ottagona. Photo: Paola De Pietri.

Fitting out of the entrance area of the Palazzo dell’Arte, Triennale, Milan, 1994-95. The large glass door leading to the gallery. Photo: Francesco Radino.

Amoruso Lonoce apartment, Brindisi, 2012. Photo: Massimo Farenga.

Notes

1 On the context of the education that Riva received, especially at university in Venice, see for example P, Nicolin, “For Umberto Riva,” in M. Zardini and P. Nicolin, Umberto Riva (Barcelona: Gustavo Gili, 1993), 11-15.

2 G. Scarpini, “Umberto Riva: due architetture,” Domus, no. 476 (July 1969), 7.

3 U. Riva in B. Danese, M. Romanelli and J. Vodoz, eds., Umberto Riva: Moving from Painting (Paris: Association Jacqueline Vodoz et Bruno Dainese, 1997), 18-19.

4 U. Riva in A. Felice, ed., Trentanove domande a Umberto Riva (Naples: Clean Edizioni, 2004), 28.

5 U. Riva in “Quattro interviste: Enzo Mari, Umberto Riva, Tobia Scarpa, Gino Valle,” ed. M. Bottero and G. Scarpini, Zodiac, no. 20 (1970), 31.

6 Umberto Riva: Album of Drawings, Quaderni di Lotus, no. 10 (Milan: Electa, 1988).

7 P. Nicolin, in Umberto Riva: Album of Drawings, 7.

8 U. Riva in Felice, Trentanove domande a Umberto Riva, 44.

9 Riva was responsible for the layout of the 4th issue (1961) of Superfici, edited by Leonardo Fiori.

10 For example, Riva designed the covers of issues number 18 (1969), 19 (1970), 20 (1971) and 22 (1973) of Zodiac.

11 See G. Canella, “Testimony for Umberto”, in Umberto Riva: Album of Drawings, 11.

12 U. Riva in conversation with the author, November 2, 2016.

13 For an analysis of Riva’s painting see: M. Bottero, “The Experimentalism of Umberto Riva,” in Umberto Riva: Album of Drawings, 99-112; Danese, Romanelli and Vodoz, eds., Umberto Riva: Moving from Painting.

14 U. Riva in Felice, ed., Trentanove domande a Umberto Riva, 31.

15 On his lighting design see among others: “Appendice: le opere di design,” in C. Pietrucci, Umberto Riva. La chiesa di San Corbiniano a Roma (Ostia Lido, Rome: Bibliolibrò, 2015), 120-37; B. Finessi, Umberto Riva. E63 – Lem, catalogue of the exhibition at the Galleria Antonia Jannone, November 17, 2015-January 9, 2016); catalogue printed in 500 copies.

16 U. Riva in “Umberto Riva: In the Beginning There is Light,” Abitare, no. 321 (1993), 134.

17 U. Riva in “Umberto Riva: In the Beginning There is Light,”134.

18 U. Riva in “Quattro interviste: Enzo Mari, Umberto Riva, Tobia Scarpa, Gino Valle,” 30.

19 Ibidem.

20 Bottero, “The Experimentalism of Umberto Riva”, 111.

21 See Canella, “Testimony for Umberto,” 11-16.

22 On this subject see for example: M. Dalai Emiliani, Per una critica della museografia del Novecento in Italia (Venice: Marsilio, 2008); S. Polano, Mostrare: l’allestimento in Italia dagli anni Venti agli anni Ottanta (Milan: Lybra immagine, 2000); A.C. Cimoli, Musei effimeri. Allestimenti di mostre in Italia 1949-1963 (Milan: Il Saggiatore, 2007); P. Falguières, “L’arte della mostra. Per un’altra genealogia del white cube,” in P. Duboÿ, Carlo Scarpa. L’arte di esporre (Monza: Johan & Levi, 2016), 15-49.

23 On this theme see for example F. Bernardelli and F. Poli’s recent Mettere in scena l’arte contemporanea (Monza: Johan & Levi, 2016).

24 Danese, Romanelli and Vodoz, eds., Umberto Riva: Moving from Painting, 15.

25 See Canella, “Testimony for Umberto,” 16.