12 July 2019

From global warming to deforestation, from the loss of biodiversity to the impact of technology: the environmental problems we face have been the same for at least half a century; what has changed today is the urgency. In many quarters it is argued that very little time is now left to sow the seeds that will ensure coming generations have a future. And this is what also emerges from Broken Nature: Design Takes on Human Survival, the extremely eloquent title of the 22nd International Exhibition of the Milan Triennale. Running until September 1, it explores through designs, installations, meetings, debates and workshops the ways in which we can repair the broken ties between nature and humanity. It is curated by Paola Antonelli, Senior Curator of the departments of Architecture and Design and Research and Development at the MoMA in New York. Her all-embracing and radical definition of the concept of design, which spills over the confines of aesthetics into social, political, moral and, here, environmental areas, is used in this exhibition to tackle what she sees as an emergency: humanity is practically already on the verge of extinction, corrective measures need to be taken at once and these inevitably require a total rethinking of our relationship with nature, other species and our own communities. So as a delineator of solutions, design can offer concrete, innovative and versatile indications of the direction in which we need to go, but only if seen as a “well-conceived strategy of reparations.”1 We talked to her about it.

Anna Citelli and Raoul Bretzel, Capsula Mundi, 2003. Photo: © Francesco D’Angelo. Courtesy Anna Citelli and Raoul Bretzel.

In the catalogue you say: “Our only chance at survival is to design our own beautiful extinction.”2 You’re really convinced of this?

I am. Death is part of life, both of an individual and of a species. The environmental, social, economic and cultural upheavals that have overtaken the planet in the last two centuries are a reminder that our end is inevitable. And probably nigh. The manner and time lie beyond our possibility of comprehension. What is certain is that life on the planet as we know it is going to change radically.

Yet Broken Nature is founded on the key concept of “restorative design,” so a germ of hope is there.

Taking a realistic look at the future of our species does not mean being cynical: on the contrary, it is possible to maintain our lucidity and be conscious of our limitations, of what is happening, without losing the desire to find a “cure.” The aim of Broken Nature is precisely to examine the ways in which design can help us to conceive a better future, or rather a more elegant ending, so that our species, once it is extinct, may be remembered positively by whatever comes after it. My hope and that of the group of curators, made up of Ala Tannir, Laura Maeran and Erica Petrillo, is to make it clear that environmental questions are not separate issues, but are part instead of a highly intricate mesh of contemporary problems.

Our is an era dominated by human action, the most advanced phase of the Anthropocene. Humanity, you argue, has literally wiped out the natural and cultural diversity of the planet. Where can we pin the main responsibility? On governments?

Not necessarily. The UN’s Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) published on May 6 last an alarming and detailed report on damage to the environment, and many countries have precise laws on the matter: Finland, Iceland and Sweden head the list, while Italy and the USA are not even in the top twenty nations. Let’s say that the responsibility is not just political, or of governments.

In any case a long-term vision of the protection of the planet is lacking. Perhaps it is not possible to imagine and implement one due to the relentless process of change that characterizes contemporary society, or perhaps it is too late.

It is not a matter of possibility, but of necessity. It is imperative that we turn our back on the shortsighted vision that has marked the political, economic and cultural course taken over the last few decades. Many of the designs in the exhibition insist precisely on the importance of adopting a long-term perspective.

Design, from the industrial viewpoint, is based on innovation, on the consumption and production of wealth, from a perspective that takes only superficial account of sustainability, with few exceptions. How can we reconcile the economic requirements of design and those of the environment

They are not irreconcilable requirements, and it is innovation that makes the difference. Let’s take an interface that makes possible communication between people who are thousands of kilometers apart, perhaps from a state in which censorship is imposed to one in which the freedom of the press is guaranteed. Intelligent design favors the circulation of ideas and improves people’s lives. Critical and aware citizens have the power to influence the behavior of industry and the market, reducing the impact that consumption has on the environment in which we live.

Kosuke Araki, Anima, charcoal, food waste, urushi, 2018. Photo and courtesy: © Kosuke Araki.

On the subject of citizens, do you think that Broken Nature is suited to all sections of the public? To whom would you recommend it in particular?

For me it was natural to aim the exhibition at as broad a swathe of the public as possible: it can be visited and appreciated by experts in the sector as well as people with no inside knowledge. I hope it won’t sound banal if I say that I recommend it in particular to children. The new generations are aware that they are soon going to inherit a sick world that needs to be cured, and are looking for solutions. This is the promise of Broken Nature: to share ideas, plans and means able to stimulate the interest of those who are sensitive to the fate of our planet. The enthusiasm with which swarms of students have peacefully invaded the Triennale on the occasion of the Fridays for Future has been moving and has given me hope.

Stefano Mancuso has curated the largest stand, that of the Nation of Plants: vegetation is presented as if it were a country in its own right and a strong feeling of empathy is established with it.3 Are the vegetable, mineral and animal worlds all on the same plane?

They are interconnected worlds. Strengthening the ties between them means fostering a richer and more variegated existence. The biosphere is a shared environment that, above and beyond the struggle for survival of individual specie, will never permit a single form of life to predominate at the expense of the others. In order to survive, and since they share the same fate, human and nonhuman beings have to reach a point of equilibrium. There are numerous designs in Broken Nature that try to forge a new language—visual, oral, empathic or some other kind—capable of promoting a sort of multispecies justice, a more inclusive one. Which can mean many things: struggling for the emancipation of bees, setting up refuges for insects, ensuring the safe repatriation of seeds, living like a goat for a few days or documenting one’s own sincere identification with a boulder.

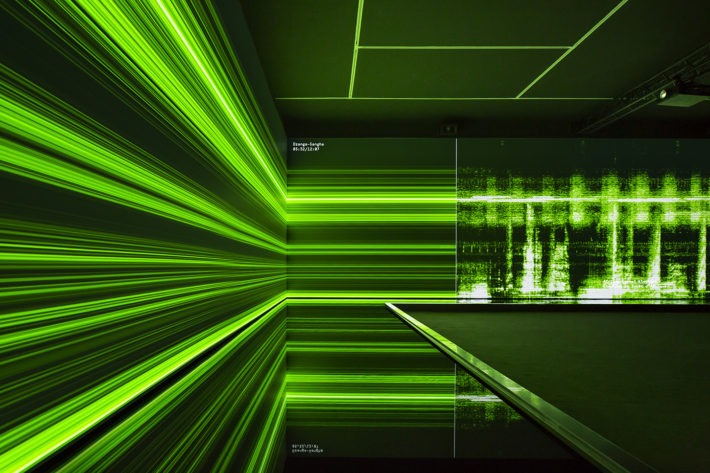

In the installation The Great Animal Orchestra by Bernie Krause and United Visual Artists the progressive destruction of biodiversity is represented by the loss of natural sounds, represented in graphic lines that gradually grow thinner. What emerges here is the theme of giving concrete expression to certain phenomena that seem remote and intangible. How did you work on this?

In effect, The Great Animal Orchestra, which has been created on the initiative of the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain in Paris, is one of the highlights of the exhibition. Traveling around the world in search of sounds of nonhuman origin, Bernie Krause has recorded the noises animals make for decades and studied their organization, assembling over five thousand hours of recordings in a variety of habitats. United Visual Artists then came up with a translation of Krause’s soundscapes into visual form: the result is an immersive installation with a very powerful impact in which the vast riches of the global aural heritage is made visible, material. This is not just a synesthetic trick, but a project that shows how art and design can be used as means of raising awareness and catalysts of positive change. If, as the philosopher Bruno Latour claims, the problem of the understanding of climate change is above all a question of language, that is of how to translate enormous amounts of data and often abstract events in a comprehensible way, The Great Animal Orchestra helps the visitor to grasp what is at stake.

Kelly Jazvak in collaboration with the geologist Patricia Corcoran and the oceanographer Charles Moore, Plastiglomerate #9, plastic detritus and beach sand, 2013. Photo: © Jeff Elstone. Courtesy Kelly Jazvak and Fierman Gallery.

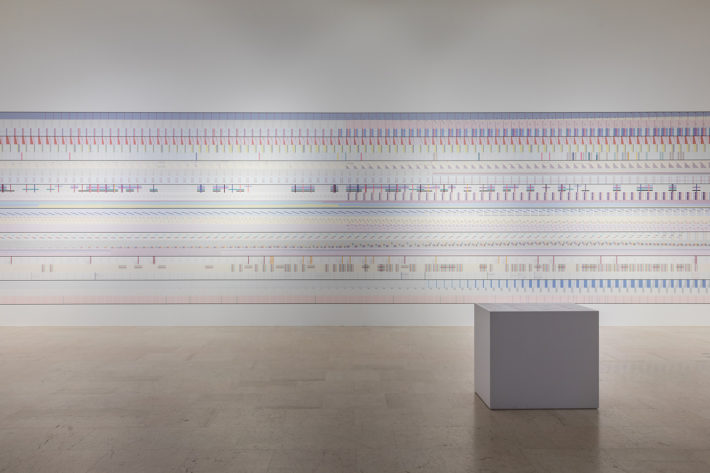

The representation of complex data as a key to understanding the phenomenon of environmental degradation can also be found in the dialogue between the large images from NASA that show some of the most radical changes that have occurred on the Earth, and The Room of Change: a work of data visualization conceived by Accurat that illustrates the relationship between the global dimension and the individual one in the dynamics of great transformations. At the root of momentous changes, we could add, always lie personal choices.

NASA’s satellite images and the Accurat studio’s visualization are part of the opening section of the exhibition, in which the reality of the dramatic anthropogenic changes undergone by our planet in past decades is presented. Changes that have been brought about as a result of human behavior and that in their turn have had, and still have, an impact on people’s lives. This is also true in a positive sense. Buckminster Fuller argued that every single human being can be a trim tab, the tiny mechanism set on the rudder of a ship that helps it to change direction. Although the bringing about of a positive change cannot depend solely on individual choices (ethical, political or of consumption), the transformation of daily habits does produce significant effects in terms of their impact on the environment. In this sense, designers can contribute in a substantial way to the promotion of models of sustainable consumption through the creation of products, services and designs with a reduced environmental impact, insisting on human rights and developing a greater collaboration between communities by involving different social groups.

The Nanohana Heels project of the British/Japanese designer Sputniko! (Hiromi Ozaki), with high-heeled shoes that sow rapeseeds, reflects on an extremely topical theme, that of sustainable fashion. An urgent and complex challenge.

Yes, it’s a theme I’ve been working on since the time of Items: Is Fashion Modern?, the exhibition I curated at the MoMA in 2017. For Broken Nature too we have selected several projects that focus on fashion and sustainability. Nanohana Heels, of course, which imagines how to exploit the ability of rape plants to absorb radioactive substances from the soil and facilitate the rebirth of land poisoned by the nuclear disaster of Fukushima. Another important project in this sense is Alexandra Fruhstorfer’s Transitory Yarn, a system used to make knitted garments that can be unraveled and reknitted over and over again, in a perfect circularity and adhering to a logic antithetical to that of so-called fast fashion. And I would also like to mention the fantastic collection of clothes called Seated Design, created by the fashion designer Lucy Jones for people confined to a wheelchair. It may not be the most traditional way of thinking about the notion of sustainability, but in 2019 “sustainable fashion” also means being sensitive to the needs of different kinds of bodies.

Sputniko! (Hiromi Ozaki), Nanohana Heels, 2012. Photo: © Naoki Ishizaka. Courtesy Sputniko!

Broken Nature promotes an idea of design that overcomes traditional barriers, focusing on introducing innovation into processes, environmental, political and social dynamics, relations between people, phenomena of migration.

Our reality is made up of complex and interconnected systems that differ widely from one another. We have to recognize, for example, that climate change, rising water levels and pollution do not have the same impact on everyone and on all forms of life. In this sense, environmental degradation is closely tied to questions of economic development and social justice. Biodiversity or the extinction of some species should also be viewed in the light of phenomena like migration, global political stability and the inequality of peoples. So Broken Nature also looks at sustainability in terms of fundamental structures like family, gender, race, class and nationality. In this sense, it was a natural choice to give prominence to a number of projects with a markedly political character, such as Teddy Cruz and Fonna Forman’s The Political Equator, which explores the social, economic and political interdependence that characterizes some of the most disputed frontiers in the world. Or The Crime of Rescue – The Iuventa Case, a video made by Forensic Oceanography and Forensic Architecture (two research institutes based at Goldsmiths University in London) that uses architectural representation to conduct a parallel inquiry exonerating a German rescue ship seized by the Italian authorities in August 2017 for suspected collusion with people smugglers.

In the exhibition, artificial intelligence, nanotechnology and biogenetics become effective allies in the development of projects of restorative design

Yes, there are several projects that celebrate the restorative potential of technologies: an example is Resurrecting the Sublime by Christina Agapakis, Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg and Sissel Tolaas, which reproduces the scent of some extinct flowers through advanced genetic engineering. On a different plane, Kate Crawford and Vladan Joler’s Anatomy of an AI System uses a high- resolution map to describe the vast planetwide network that underpins the birth, life and death of a single Amazon Echo, drawing attention to the complex mechanisms of exploitation of resources required to make, distribute and dispose of a cylindrical speaker just 25 cm high.

Still on this theme, Formafantasma’s Ore Streams tackles the problem of electronic waste.

Let us say straightaway that the problem does not lie in the invention of electronic products in themselves, but in their excessive consumption, in the absence of efficient practices of recovery and recycling and in strategies of planned obsolescence. Thinking about these aspects, Andrea Trimarchi and Simone Farresin of Formafantasma have come up with an ambitious research program on the recycling of electronic waste to be carried out over the course of three years, commissioned by the NGV Triennial of Melbourne in 2017 and subsequently expanded for the Milan Triennale. The invitation is to meditate on the role of design in making more responsible use of resources, reappraising even the very notion of “waste” produced by humans. “Waste,” if subjected to a process of regeneration, can become a new material, a resource instead of a cost.

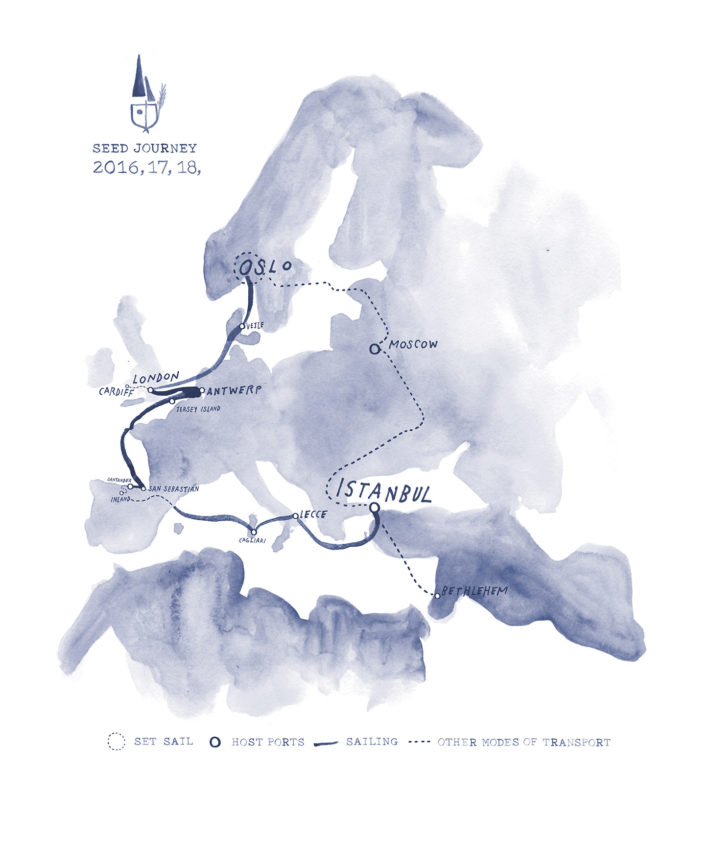

Futurefarmers (Amy Franceschini), Seed Journey, map, watercolor on paper, 2017. Courtesy Futurefarmers.

Even our lifeless bodies can have less impact on the environment, as Anna Citelli and Raoul Bretzel’s Capsula Mundi demonstrates: an egg-shaped container, made out of biodegradable material, in which the ashes or body of a deceased person are placed. Do we really have to rethink all our habits?

Of course. The global crisis of waste is an environmental catastrophe that involves all human activities, with no exceptions. The most interesting results can be obtained by reexamining our daily habits, as citizens and consumers, even the ones which we usually pay no attention to. And it is a reconsideration that should be promoted first of all by those who are professionally involved in the generation of ideas, products and services: designers, engineers, architects, city planners, scholars, critics, curators, creatives. In 2019 we can no longer allow ourselves to put off dealing with the problem.

Are there any works or projects, in addition to those already mentioned, that sum up the crucial aspects of this Triennale?

It is a very rich program, the fruit of a combined effort, with around a hundred loans. Each of the ideas selected offers in its own way a unique perspective of analysis and design. Among them I can cite objects and installations of contemporary design like Dominique Chen’s NukaBot, Google Brain’s Whale Song and the heaps of sand, plastic and rock nicknamed “plastiglomerates” by the artist Kelly Jazvac. Other milestones are Pettie Petzer and Johan Jonker’s Hippo Roller, Elemental’s project of “incremental” social housing, Martino Gamper’s iconic series 100 Chairs in 100 Days or Eyewriter, a pair of low-cost glasses with eye-tracking technology and customized software designed by a group of hackers and artists. Some of these have already had an indelible impact on society and on the way in which human beings relate to the world.

Broken Nature has gone well beyond the bounds of the exhibition, organizing symposia, debates, public meetings and workshops. Does the traditional concept of an exhibition still make sense today?

I may be biased, but the answer is yes: exhibitions of art and design can still be valid, relevant and full of meaning today. For this to happen, however, museums and cultural institutions have to reclaim their essential role in a democratic society, proposing themselves as temples of free expression, public forums in which citizens can meet and discuss, feeling listened to and protected; or again, workshops in which aware citizens develop innovative ideas and hone their own intellectual tools. If we picture the entity of the “exhibition” as a river, I like to think that this river can overflow, burst its banks and fertilize unexplored terrain with its lifeblood. It with these premises that we have conceived Broken Nature, defining a complex program that has been developed before and during the exhibition and that, I hope, will continue to develop afterward as well. In addition, there is the online platform that offers amplification of various kinds, making the curatorial process participatory and transparent.

Caroline Slotte, from the series Damaged Goods, reworked secondhand plastic and ceramic materials, 2009. Photo: © Joakim Bergström. Courtesy Caroline Slotte.

What were the main difficulties you encountered in realizing such an ambitious project?

There are difficulties in every project, they are part of life. Last year I organized with the research and development department of the MoMA an event with the title Friction, a sort of celebration of the little obstacles that punctuate our daily lives. Obstacles to be tackled and overcome, be they great or small, are an essential element of every achievement. And difficulties can also become a motivation, a positive spur that drives you to do more. I always say that anger and fear are my greatest strengths.

Today everything, or almost everything, is design: from a Beretta pistol to typefaces, passing through furniture, fashion, built spaces, videogames, food and the installations of Broken Nature. The word has taken on an ever broader meaning. What does design signify for you?

Design is one of the highest expressions of human creativity, and designers should always feel responsible to the beings—human and nonhuman—that inhabit the planet. There ought to be a sort of Hippocratic oath, like doctors have.

Has Broken Nature changed you?

Undoubtedly. Working on this exhibition has been an opportunity to grow, I will never be the same again. I hope that this will also happen to those who visit the exhibition: that they will come out of it changed, more aware.

We would like to thank Erica Petrillo for her collaboration.

Sonam Wangchuk of the Students’ Educational and Cultural Movement of Ladakh (SECMOL), with Sonam Dorje and Simant Verma, Ice Stupa, artificial glacier, 2013-14. Photo: © Lobzang Dadul. Courtesy SECMOL.

Bernie Krause and United Visual Artists, The Great Animal Orchestra, 2016, multimedia installation, 1 hour and 32 minutes, collection Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain (acquisition 2017). View of the exhibition The Great Animal Orchestra, Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, Paris, 2016. Photo: © Luc Boegly. Credits: © Bernie Krause © United Visual Artists.

Bernie Krause and United Visual Artists, The Great Animal Orchestra, 2016, multimedia installation, 1 hour and 32 minutes, collection Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain (acquisition 2017). View of the exhibition The Great Animal Orchestra, Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, Paris, 2016. Photo: © Luc Boegly. Credits: © Bernie Krause © United Visual Artists.

Bernie Krause and United Visual Artists, The Great Animal Orchestra, 2016, multimedia installation, 1 hour and 32 minutes, collection Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain (acquisition 2017). View of the exhibition The Great Animal Orchestra, Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, Paris, 2016. Photo: © Luc Boegly. Credits: © Bernie Krause © United Visual Artists.

Accurat (Giorgia Lupi, Gabriele Rossi, Nicola Guidoboni, Giovanni Magni, Lorenzo Marchionni, Andrea Titton, Alessandro Zotta), The Room of Change, 2019. Photo: © Gianluca Di Ioia, La Triennale di Milano.

La Nazione delle Piante, curated by Stefano Mancuso, 2019. Photo: © Gianluca Di Ioia, La Triennale di Milano.

Stephan Bogner, Philipp Schmitt and Jonas Voigt, Raising Robotic Natives, Bottle Feeder, robot with 3D-printed baby bottle, 2016. Courtesy the designers.

Emilija Škarnulytė, Extended Phenotypes, 2017, from the video-installation Manifold, Lithuania, national participation in the 13th International Exhibition of the Milan Triennale, 2019. Courtesy Emilija Škarnulytė.

EOOS, view of the installation Circular Flows, Austria, national participation in the 13th International Exhibition of the Milan Triennale, 2019. Photo: © MAK/Georg Mayer/EOOS.

Formafantasma (Simone Farresin, Andrea Trimarchi), Ore Streams, Cubicle 1, 2017. Photo: © IKON. Courtesy Nicoletta Fiorucci, London, and Giustini/Stagetti, Rome, with the support of Stimuleringsfonds and the National Gallery of Victoria.

Thomas Thwaites, Goatman, 2016, with the support of the Wellcome Trust. Photo: © Tim Bowditch. Courtesy Thomas Thwaites.

Grandeza Studio, Teatro Della Terra Alienata: Fracking, Australia, national participation in the 13th International Exhibition of the Milan Triennale, 2019. Photo: © Grandeza Studio.

Buro Belén (Brecht Duijf, Lenneke Langenhuijsen), SUN+, Unseen Glasses, 2012. Photo and Courtesy: © Buro Belén.

Adidas Parley Ocean Plastic footwear, 2016. Courtesy Adidas.

Studio Folder (Marco Ferrari, Elisa Pasqual), Italian Limes, project mapping the shift in national borders following the melting of glaciers in the Alps, 2014-18. Photo: © Delfino Sisto Legnani. Courtesy Studio Folder.

Lucy Jones, Seated Design, worsted wool herringbone, 2017. Courtesy Lucy Jones.

Pettie Petzer and Johan Jonker, Hippo Roller, device for collecting and carrying water, 1991. Courtesy Hippo Roller.

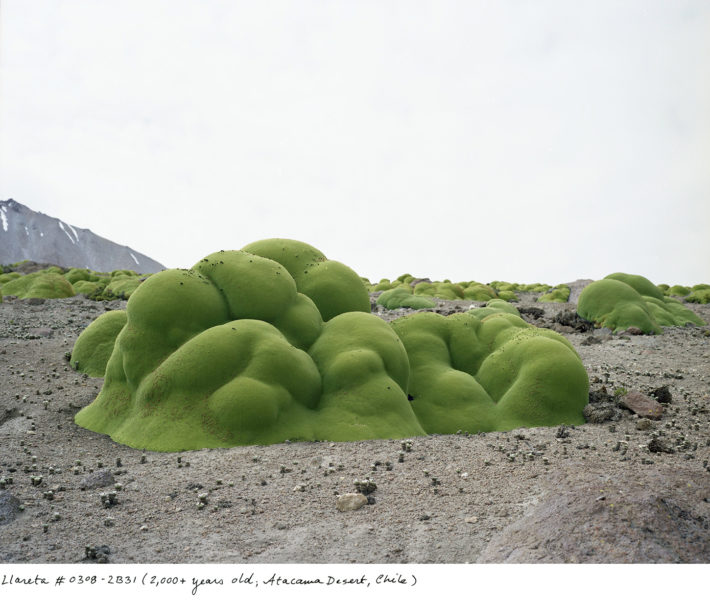

Rachel Sussman, Llareta #0308-2B31 (2000+ years old; Atacama Desert, Chile), 2008. From Sussman’s book The Oldest Living Things in the World (University of Chicago Press, 2014). Courtesy Rachel Sussman.

Notes

1 Paola Antonelli, “Broken Nature,” in Broken Nature. XXII Triennale di Milano, catalogue of the exhibition at the Triennale di Milano (Milan: Mondadori Electa, 2019), 19.

2 Antonelli, “Broken Nature,” 40.

3 See Stefano Mancuso, La Nazione delle piante (Rome-Bari: Laterza, 2019).