19 December 2016

We met Armin Linke (born in Milan in 1966, resident in Berlin) at the PAC (Padiglione d’Art Contemporanea) in Milan, in the midst of preparations for The Appearance of That Which Cannot be Seen, curated by Ilaria Bonacossa and Philipp Ziegler. It is the artist’s first major solo exhibition in Italy and for it he has reworked the project that was staged in different instalments at the ZKM (Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie) in Karlsruhe in 2015-16. For over twenty years, Linke has been documenting the symptoms and manifestations of globalization all over the world, assembling a corpus of more than 20,000 images that range from the premises of the European Central Bank to the museum at Babylon in Iraq and from the Saharawi refugee camp in Algeria to the flower auction at Aalsmeer in the Netherlands. In keeping with the participatory approach that characterizes many of his projects, Linke has invited eight scholars, academics and experts in various fields to hold a dialogue with his photographs. Ariella Azoulay, writer, curator, filmmaker and theorist of visual culture, as well as professor of Modern Culture and Media at Brown University; Lorraine Daston, director of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin; Franco Farinelli, professor of Geography and dean of the department of Philosophy and Communication at Bologna University; Irene Giardina, founder of a laboratory devoted to the application of quantum physics to the study of biological systems and collective animal behavior and a professor in the department of Physics at La Sapienza University in Rome; Bruno Latour, French anthropologist and professor at the Paris Institute of Political Studies; Peter Weibel, chairman and CEO of the ZKM and professor of Media Theory at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna; Mark Wigley, a theorist of architecture from New Zealand; and finally Jan Zalasiewicz, geologist and chairman of the Anthropocene Working Group. Out of the exchange between the artist and his co-authors came The Appearance of That Which Cannot be Seen: a chorus of voices, texts and photographs that, in recounting the history of design, economics, technology and infrastructure, reflect—and make us reflect—on the actions of humankind and invite us to listen to, observe and interpret the new artificial and natural landscapes we inhabit.

PAC – Padiglione d’Arte Contemporanea, Milan, Italy, 2016. © Armin Linke.

As soon as we enter, we are greeted by a photograph with a view of the PAC. How did the exhibition arise and how did it end up here?

The exhibition was first staged at the ZKM as part of a program entitled Global organized by Peter Weibel, which consisted of a series of exhibitions on the interpretation of the contemporary world. On that occasion, the exhibition was split into five episodes, five successive theatrical acts. Thanks to the invitation I received from Ilaria Bonacossa, here at the PAC I have had the opportunity to present the whole thing in a single space, all at the same time. To the five voices of experts already present, we have added those of Franco Farinelli, Lorraine Daston and Irene Giardina: it is the first time that the exhibition has been presented in such a complete manner. We have tried to work specifically on the architecture of the Padiglione d’Art Contemporanea, a very special place for me—it is no coincidence that we have included an interview with the architect Jacopo Gardella, who worked with his father Ignazio on the reconstruction of the building after the Mafia destroyed it with a bomb in 1993. A genuine tribute to the PAC. The origin of the exhibition lies in a series of workshops at which—after a first experiment conducted with the philosopher Bruno Latour, who had asked me for some images to accompany his studies—I invited experts to choose one or more photographs out of a number I had selected in advance from my archives, commenting on them and using them to illustrate their respective fields of research. By recording our conversations, we worked on the relationship between images and texts, dividing them up by themes: the art system and the calling into question of photography; the idea of atmosphere; architecture and infrastructure, interpreted as pipes and fabrics in the words of Mark Wigley; finally, economics and politics. From here, where the talk is of nature and botanical gardens as an economic resource, we see the garden of the Villa Reale. The PAC has an interesting relationship with the outdoors, of which Bruno Latour speaks when reflecting on the connection between “inside” and “outside.” The exhibition and book (published by Silvana Editoriale, interviewer’s note) are treated in different ways: while the subdivision here is thematic, the book is arranged by authors. They often talk about the same photographs, so that in the book some of them are repeated, something that does not usually happen in publishing.

Adam Lowe, Factum Arte, Madrid, Spain, 2011. © Armin Linke.

Many of your projects are the fruit of a process carried out in collaboration with other professional figures, whose contribution is part of the work. What are the motivations and the objectives that underlie this method?

In this specific case, I was interested in using photography as a springboard for a dialogue and for the raising of questions, rather than presenting it as a finished work. On other occasions I have found myself working in a group not as a photographer, but as a curator—it is interesting to bring a number of roles together, but also to perform different ones within a group. As in the case of the Double Bound Economies project: on that occasion, we invited various experts on economics, historians, diplomats and photographers to work on the archives of a photographer active in East Germany whose pictures of industrial products were supposed to show the accomplishments of the socialist worker as a form of ideological propaganda, but at the same time to look at how the same products were sold in West Germany to raise foreign exchange. We were interested in this sort of schizophrenia of the photographic image. Images that come from different projects, made with different agendas (some are commissions), can be read in contradictory ways, revealing the impotence of photography. It is in fact a social exercise: if we were to train ourselves to decipher the codes of images, we might find we could gain a better understanding of how our world is constructed, and provide ourselves with the means we need to plan it in a different way.

CNR, National Research Council, Fermi conference hall, Rome, Italy, 2007. © Armin Linke.

While the dialogue between voices, texts and images establishes a narrative structure, the design of the exhibition suggests something temporary, a workshop. Once you had assembled the pictures and conversations, how did you work on their presentation?

The exhibition functions likes a hypertext, a webpage, that you can click your way around. When you’re online you can decide which route you want to take, and that is what we have tried to do here: to create a landscape, a garden, a forest to immerse yourself in, letting yourself be guided by the soundscape, by reading the texts or by looking at the photographs. The idea was not to have a fixed route—typical of the way many exhibitions follow the lines of the walls— and leave it open instead. In this sense, an important part was played by the collaboration with the graphic designers Linda van Deursen and Jan Kiesswetter, the artist and photographer Alina Schmuch and the designer Martha Schwindling, with whom I worked for a year on the development of the system of display. We wanted to pare everything down to a minimum, and we arrived at these panels that are used to support the frame and become the caption: under the picture, there is the title with my explanation of the context in which I took it. This is the first level, and then there is another, that of sound. We have tried to create an interface that will allow people to navigate without getting lost and without getting frustrated, giving rise to a sort of playful setting made up of information and feedback. The provisional character of this is very important for me. It is the same transience that characterizes the interpretation of an image: whence the title, The Appearance of That Which Cannot be Seen. This exhibition was different at the ZKM, and it will be again when it goes to Aachen and in particular to Geneva, a place with close ties to the economy, where there will undoubtedly be other themes to present and choreograph. The system of display draws on theatrical scenery. The hooks that support the structures are the same ones as are used on stage to change scenes rapidly between one act and the next. In a sense, we have conceived the exhibition as a workshop that could potentially be dismantled and reassembled, an experiment. If on the one hand the images are hyperrealistic, showing physical spaces where precise aesthetic, social and political processes occur, on the other the way in which they are presented alludes to the theater, the place of make-believe.

Jurong Bird Park, Singapore, 1999. © Armin Linke.

The pictures were taken on many different occasions. How has your approach to photography changed, if it has changed, over the years?

In the exhibition, through this structure, the photographs are kind of mixed up. I treat them as if they were not mine, finding a way to make them anonymous, or rather to “de-authorialize” them. Of course, there are technical differences. For example I often used to use a 6 x 12 panoramic camera, but at a certain point I found it too spectacular and so I chose a different, more intimate format. The choice also depends on the context in which the pictures are taken: sometimes it’s interesting to resort to different strategies, for instance utilizing a heavy device from the production viewpoint—like the 6 x 12, which is used in architectural photography—to take a snapshot. The constant is the use of two fixed formats, to which the image is adapted by moving it to the right or upward: inside the frame, it becomes a graphic element. The picture is adapted to an industrial standard, leaving the support visible—in one case it is 150 cm, the maximum print area available in relation to the height of the roll of paper, and in the other the dimension is 50 x 60 cm, the typical format of a precut industrial box. These details are connected with the theme of the physical reproduction of the photograph, something that interests me greatly.

Kawah Ijen Volcano Biau (Jawa Timur) Indonesia, 2016. © Armin Linke.

Who are the authors who have had an influence on you?

Rather than photography, the main influence for this exhibition has come from writing. I’m thinking of John Berger and his Ways of Seeing, for example. On the translation of the texts I worked with Mariella Dotti, Berger’s translator, precisely in order to pay homage to his work. Other important references have been Ariella Azoulay and Bertolt Brecht’s working diary, in which the author utilizes pictures from newspapers to make an interpretation that is once social and poetic. A photographer I’ve worked with is Aglaia Konrad, with whom I share the idea of presenting the photograph as a sculptural object that does not limit itself to talking about space, but becomes it.

Mies van der Rohe, Barcelona Pavilion, Barcelona, Spain, 2013. © Armin Linke.

There are over twenty thousand pictures in your archive. What criteria do you use to catalogue them?

The subject of the archive is a bit overworked, almost problematic. I’m not interested in the archive in itself, but as a means of activating something. The question is: how to make sure that the archive is kept relevant to the present and not turned into a historical relic? The process of putting things in an archive is in itself extremely boring. In this sense, it serves as a filter, because it induces you to ask yourself whether it is worth taking a photograph, knowing that afterwards you will have the very tedious job of archiving it: inserting the textual data, taking the negative, putting it in an envelope, labelling it, scanning it. It makes you wonder whether the image will have sufficient intrinsic value, whether it will lose its relevance in the space of a month (like a picture published in a journal) or at the most a year, or whether instead it will still have a function and possibly change that function over time. Knowing that you have to go through that procedure, before taking a picture you ask yourself questions that are in my view extremely sound and important. In a sense, you try to tell yourself whether the image that you are going to capture has enough levels of interpretation to be interesting and not to get stuck in the archive. The categories into which my archive is subdivided are connected mainly with the technical characteristics of the photograph and the moment of its production: analog, digital, format of the negative, where it was taken and in what context, what it represents, any additional information. Then, knowing in what channels it has been presented, at what exhibitions, I can try to sabotage my own previous use of it, try to reconsider it. The exhibition speaks of precisely this: seeing what other possible interpretations, ones that I have not succeeded in stimulating, are proposed by other people. In one very interesting part of our conversations, Ariella Azoulay criticizes the very operation of creating archives—for example, those of an institution—explaining that when we access them, we are in reality gaining access to a tagging mechanism, the kind that defines our society. The digital world is in fact characterized by labels that filter information: what doesn’t fit into a given category is ignored. In the same way, labels permit a solely superficial reading of the contents of an archive. For this reason we were interested in trying to come up with a critical interpretation not just of the images and the themes tackled, but of the use of the archive itself.

BNP Parisbas, headquarters, trading floor, Paris, France, 2012. © Armin Linke.

The Anthropocene, a thread running through your work, is attracting particular attention at the moment, after the Anthropocene Working Group requested the formalization of the term at the International Geological Congress last August. How did you get involved in studies of the Anthropocene and how do you see your future contributions to this area of research?

My interest in the Anthropocene stems in part from a commission set up by the Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin, out of which came the project entitled Anthropocene Observatory that was carried out jointly with Anselm Franke and Territorial Agency. For two years we looked at the way that the political and scientific institutions which devote their attention to the Anthropocene and climate change interface with one another on this theme, how they raise awareness, how they act. The collaboration was a very interesting one because it allowed me to look back at some things that I had begun work on twenty years earlier and recontextualize them, thinks like the construction of the Three Gorges Dam in China, or the flower fair at Aalsmeer. Although that project is finished, many others on which I’m working can be viewed through the lens of the Anthropocene: just a few weeks ago I was in Indonesia to look at the way forests are being burned down to make plantations of oil palms, and my friend Etienne Turpin told me the story of Antonio Stoppani, director of the Museo Civico di Storia Naturale in Milan in the 1880s, from 1882 to 1891 in fact—a museum that is now named after him. Stoppani had proposed the Anthropozoic era as early as 1870, and in 1875 had written an important book on geology called Il Bel Paese—which is why there is an image of the geologist on the wrapper of the cheese of the same name made by Galbani. In the years to come, however, he was almost forgotten, as many of his writings were superseded by the ideas of Darwin. What I would like to do over the next two years—more or less the length of time for which the commission will go on working—is to try to broaden these observations and find out whether it might be possible to reach some kind of conclusion. The form is not yet clear to me.

Whirlwind, Pantelleria (TP) Italy, 2007. © Armin Linke.

On the subject of form, and bearing in mind the processes of reactivation to which you subject your photographs, do you ever consider a project definitively concluded?

The film Alpi, for example, screened on the upper floor, is by necessity a finished project. However, one or two of the photographs taken during the filming are also on display and can be presented in other contexts. For me, an exhibition, a book, a film are final forms, but in the mode of the essay: they are not closed in terms of their interpretation, but as experiments. They allow me to go on seeking other configurations, themes or places of interpretation. This exhibition is a collective essay, which it will be possible to go on developing in other, different directions.

What are your projects for the future?

First of all I intend to devote my attention to this exhibition in its subsequent moves to Aachen and Geneva. In the meantime, I’m starting to work on other projects based on archives. For example, I’m working with a photographer friend, a paparazzo. I’m interested in interpreting his archive in order to try to understand how a certain type of photography, not necessarily authorial or of particular aesthetic value, can be an interesting way of looking at how our contemporary society perceives public space, and the idea of the human body.

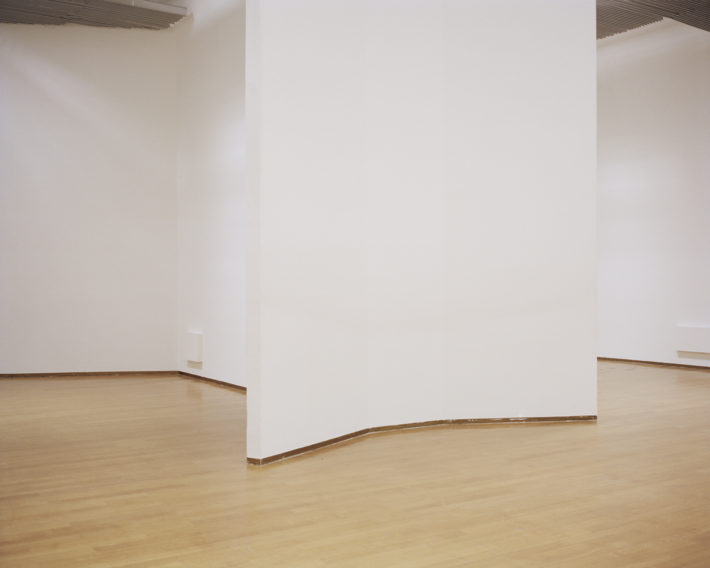

Armin Linke, The Appearance of That Which Cannot be Seen, PAC – Milan. Installation view.

Armin Linke, The Appearance of That Which Cannot be Seen, PAC – Milan. Installation view.

Armin Linke, The Appearance of That Which Cannot be Seen, PAC – Milan. Installation view.

Armin Linke, The Appearance of That Which Cannot be Seen, PAC – Milan. Installation view.

Armin Linke, The Appearance of That Which Cannot be Seen, PAC – Milan. Installation view.

Armin Linke, The Appearance of That Which Cannot be Seen, PAC – Milan. Installation view.

Armin Linke, The Appearance of That Which Cannot be Seen, PAC – Milan. Installation view.

Armin Linke, The Appearance of That Which Cannot be Seen, PAC – Milan. Installation view.