21 December 2012

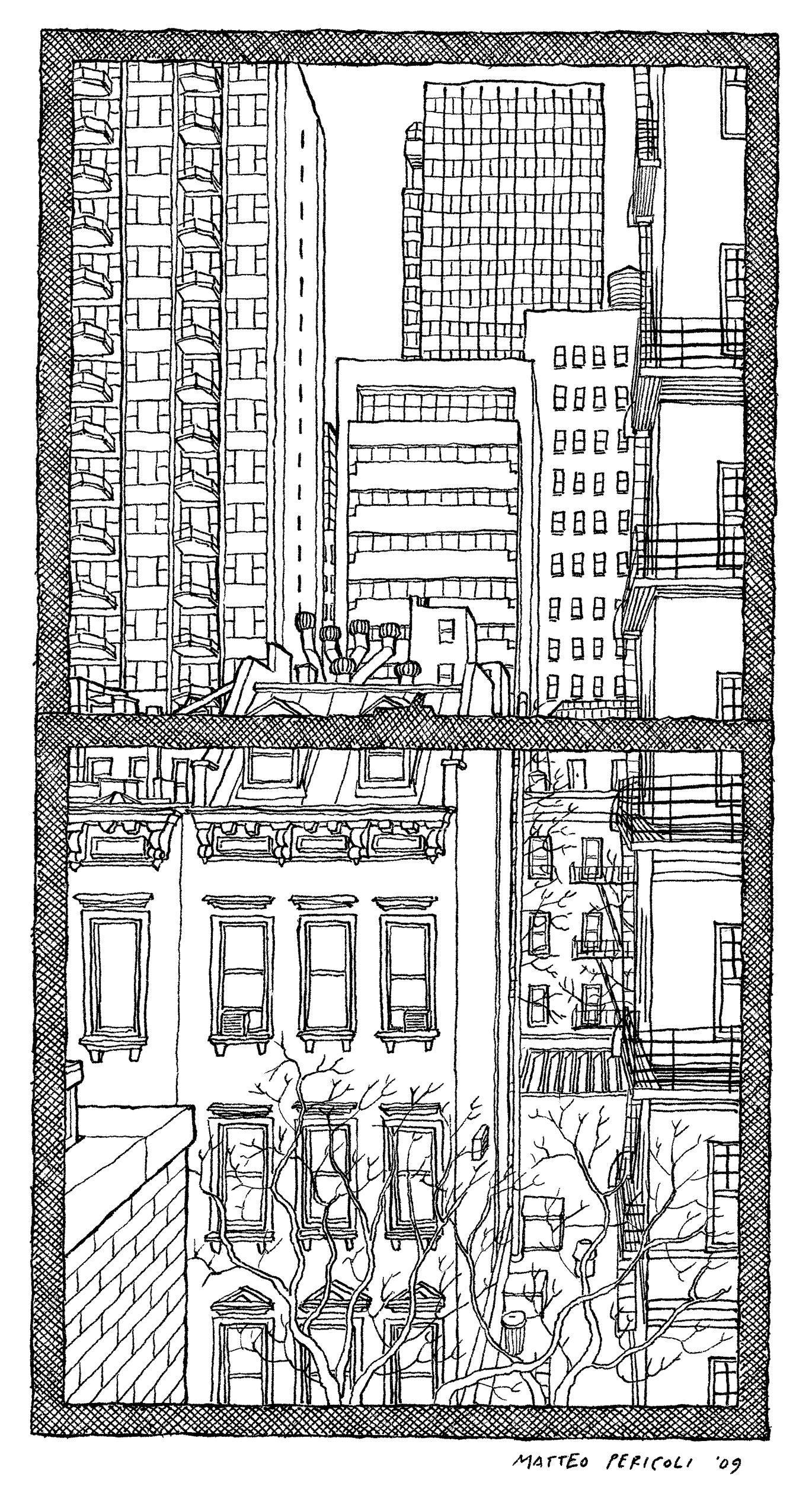

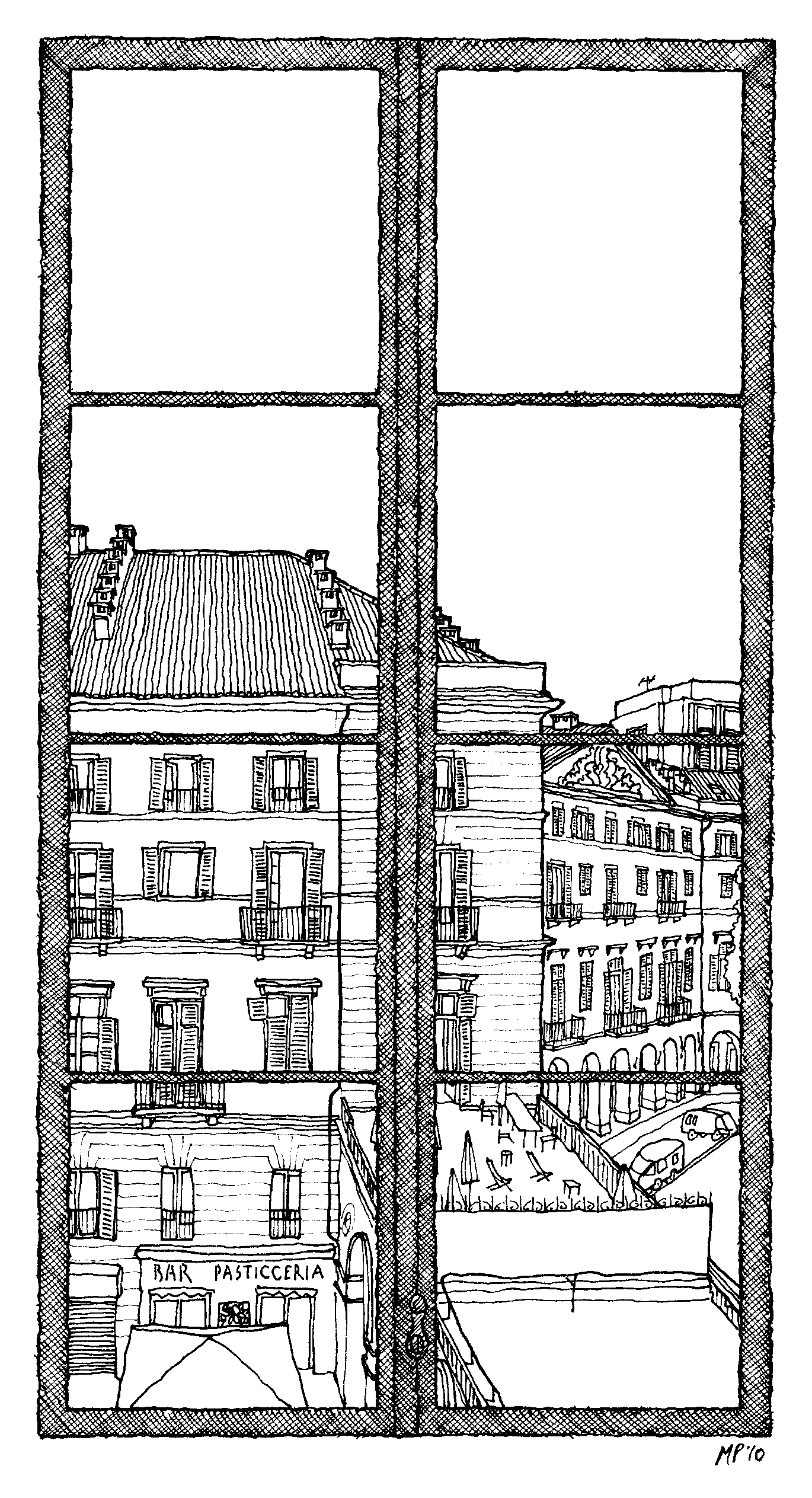

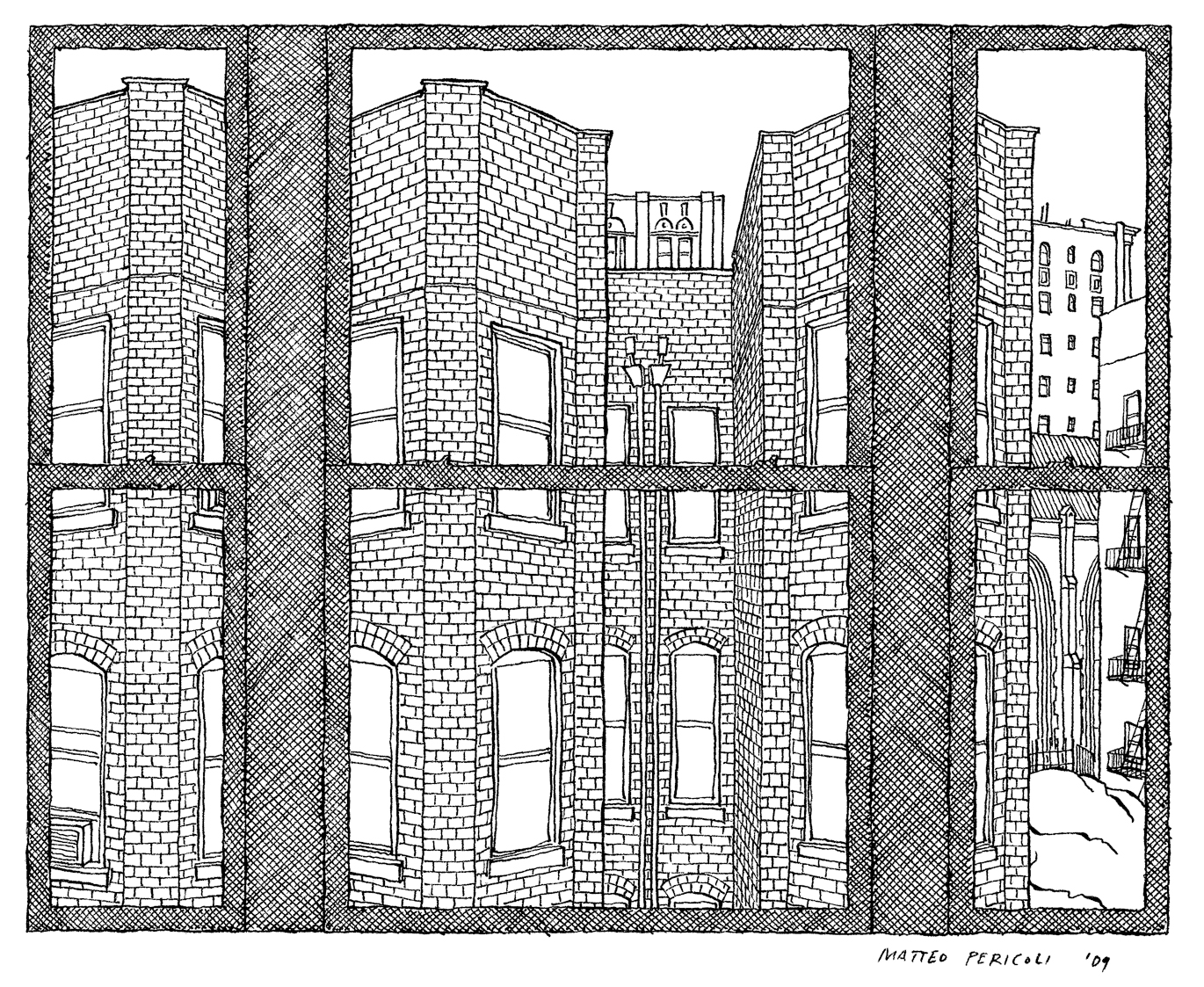

Matteo Pericoli—Milanese by birth, New Yorker by adoption—does not limit himself to drawing: rather, he uses line to tell the story of the city’s becoming. In the first place the Big Apple, the metropolis in which he has lived for thirteen years, drawing its skyline and urban views from the windows of the homes of its inhabitants. Son of an artist and an architect by training, he has published his drawings in the New York Times, the Observer, the New Yorker, La Stampa and the Paris Review. He lives and works in Turin, where he teaches architecture to students of writing at the Scuola Holden. Last month he held a solo exhibition at the Casa dei Libri in Milan, entitled Finestre di scrittori (Writers’ Windows): an ode to the intimate and hidden face of the urbs, the one visible from the windows of writers all over the world.

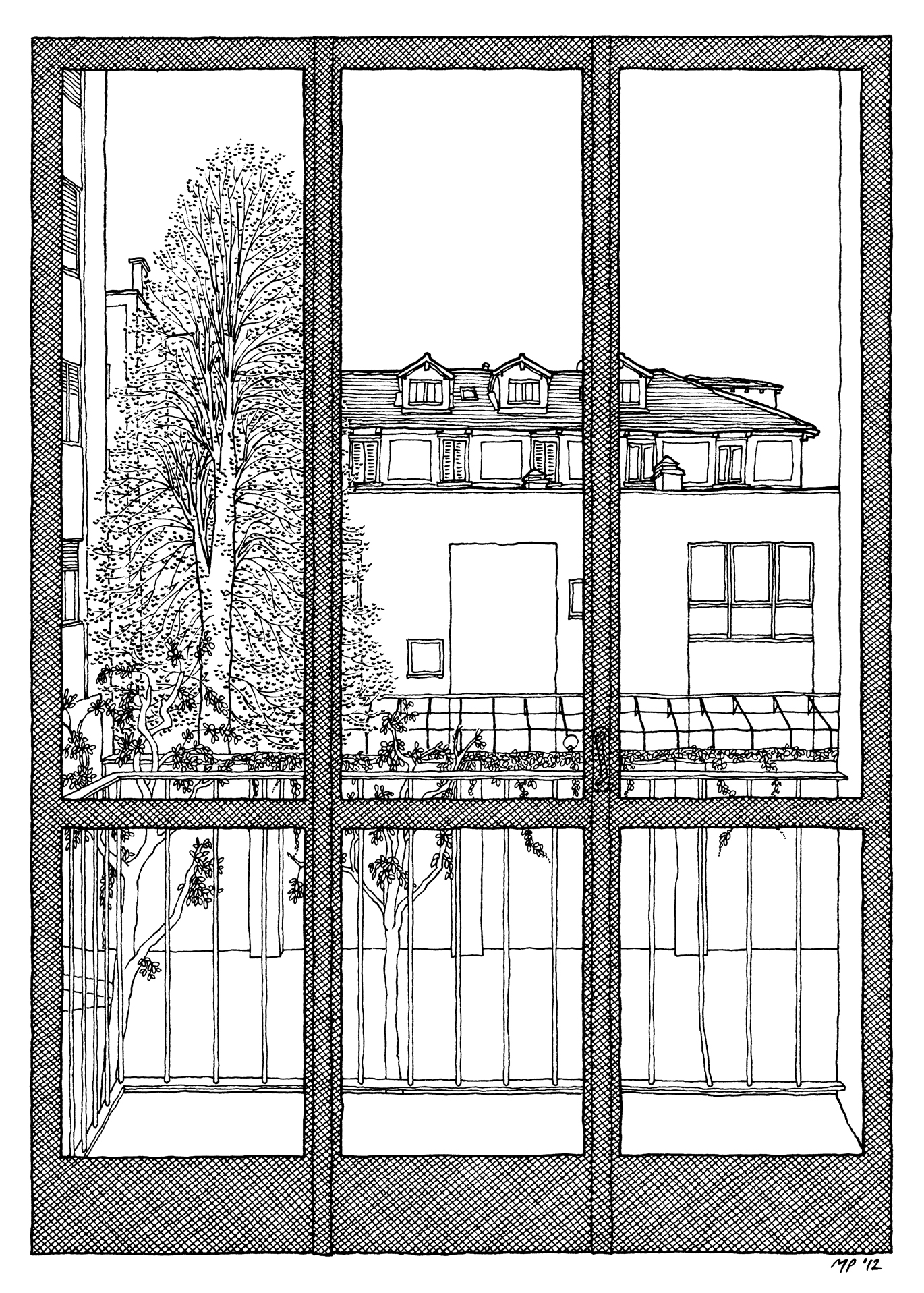

Matteo Pericoli, Tim Parks

Almost all your drawings are of cities: at times you portray the objective and rational side of the metropolis, as in the “fold-out” skylines of Manhattan and London Unfurled; at others its intimate and subjective face, the one present in the urban views of the Writers’ Windows; at yet others its visionary and imaginative aspect, as in the large murals entitled Skyline of the World at JFK airport in New York. What does a city represent for you? I’m thinking above all of New York City, in which you spent thirteen years of your life.

I was born in a city, Milan, where I lived and studied architecture until the age of twenty-six. For me Milan has never been a place that had a heart, a very strong spirit. In those years I believed that the city was merely an extremely dense amalgam of houses and the assembly point of disparate activities, a place where it was convenient to live even though you didn’t want to: I didn’t like urban reality. I would have preferred to live in the country, in the Marche, where my family had its home. Everything changed when I arrived in New York, in 1995. I realized that the city had a specific identity and that it was continually changing. New York turned out to be the opposite of my expectations: the verticality, the density, the breadth, the intense human contact. All this depended on the fact that the metropolis was nothing but a multitude of small countries and ethnic groups. I was able to perceive its triumphant vitality: I wanted to get to know it and understand it fully.

And it was in New York that you started to devote yourself to illustration and drawing.

After a brief period with Eisenman, I moved to Richard Meier’s studio, where I was put to work on the project for the Jubilee Church in Rome. Meier’s method of working is based on drawing: I drew everything by hand, including the details, and I learned to associate a precise meaning with every line. Saul Steinberg, the celebrated artist of Romanian origin, said that the terror that one of his lines might one day turn into reality prevented him from exercising the profession of architect: my fear and “sense of responsibility” with regard to the line grew enormously during that period of work. In the daytime I worked 10/11 hours in the studio, drawing buildings and details, while at night I redrew New York, a few centimeters at a time, applying the principle of the correspondence between line and real element. I started to represent the city from the outside: I thought that by drawing everything, and not just some fragments of the metropolis, I would be able to make some important discovery. I wanted to carry out a project that would be democratic and all-inclusive, avoiding relegating the representation of the city to the usual stereotypes. So I decided to go on the Circle Line, a sightseeing harbor cruise that starts from 42nd Street, circumnavigating the island of Manhattan for a total of three hours. I took the boat in order to observe the area in which I lived, the Upper West Side, from the water, taking a step back from the bustle of the urban universe. New York is a very egocentric city. It gazes at the world from above and beyond, without looking at itself. No New Yorker takes the Circle Line, only tourists do it. From the boat, suddenly, I was able to see a place steeped in silence, that seemed cut out to be portrayed from the outside. On that occasion I understood that that was the point of view from which I had to draw the whole of the city, without excluding anything.

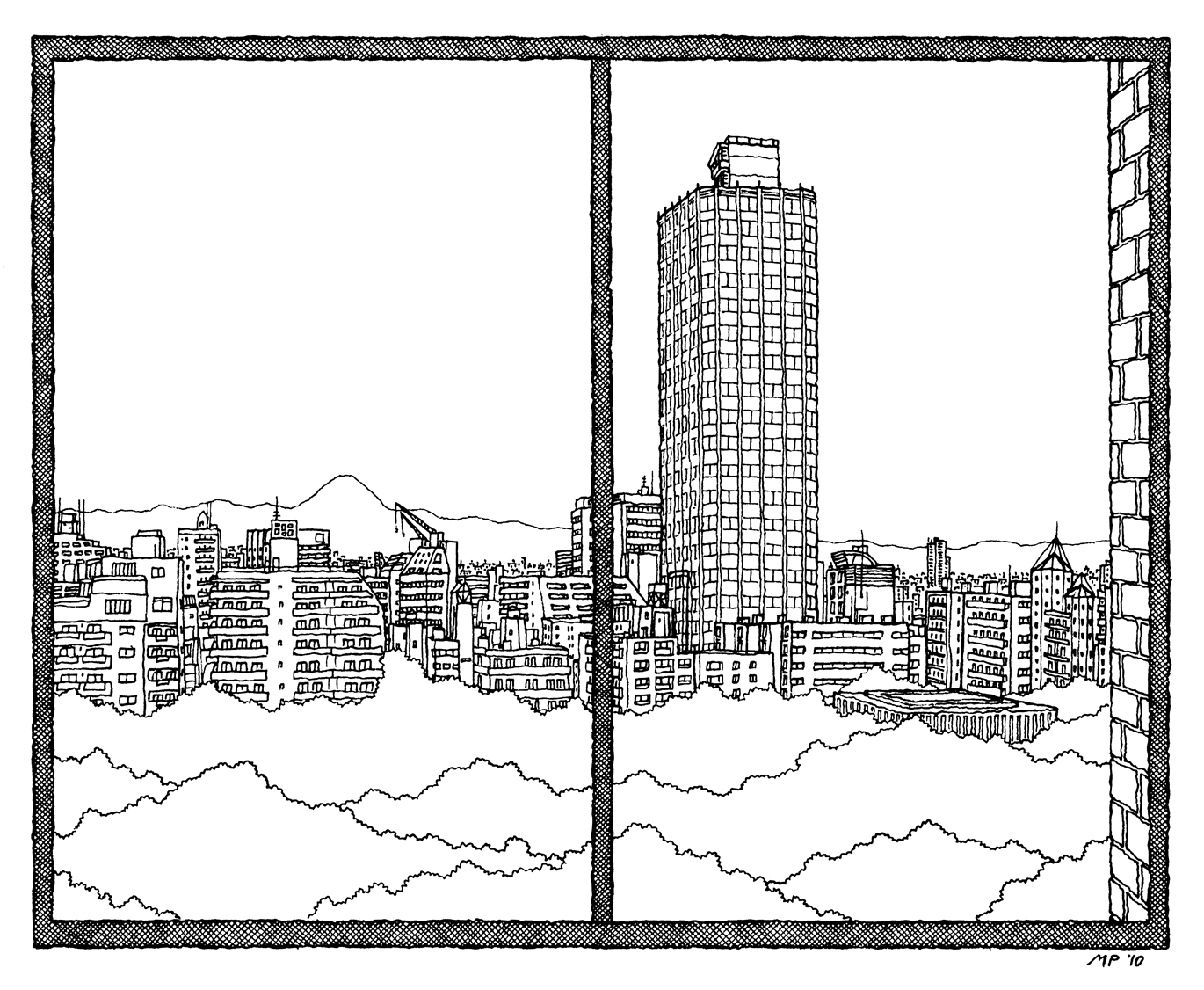

Matteo Pericoli, Ryu Murakami

And so you drew the skyline of Manhattan on two unrolled sheets of paper: one for the West Side, the other for the East Side. A sort of illustrated frieze, in which you transfigured the dramatic verticality of New York—the city conceived and perceived from the inside—into a horizontality with an inclusive and reassuring appearance—the city viewed from the boat of the Circle Line.

First I took hundreds of photographs. Then I drew and, as I went along, rolled up the sheet to my left: time was accumulated inside the roll, without me ever looking back at the sections I had drawn earlier. My home, in fact, only allowed me to unroll a few meters at a time, while the drawing reached a length of 12 meters. Those were years of intense work, prior to 2001. Later I drew the skyline of New York from the inside, from Central Park (the hole in the donut of Manhattan), on a single sheet. It was only then that I thoroughly understood the city I was living in.

How was the project of the writers’ windows born?

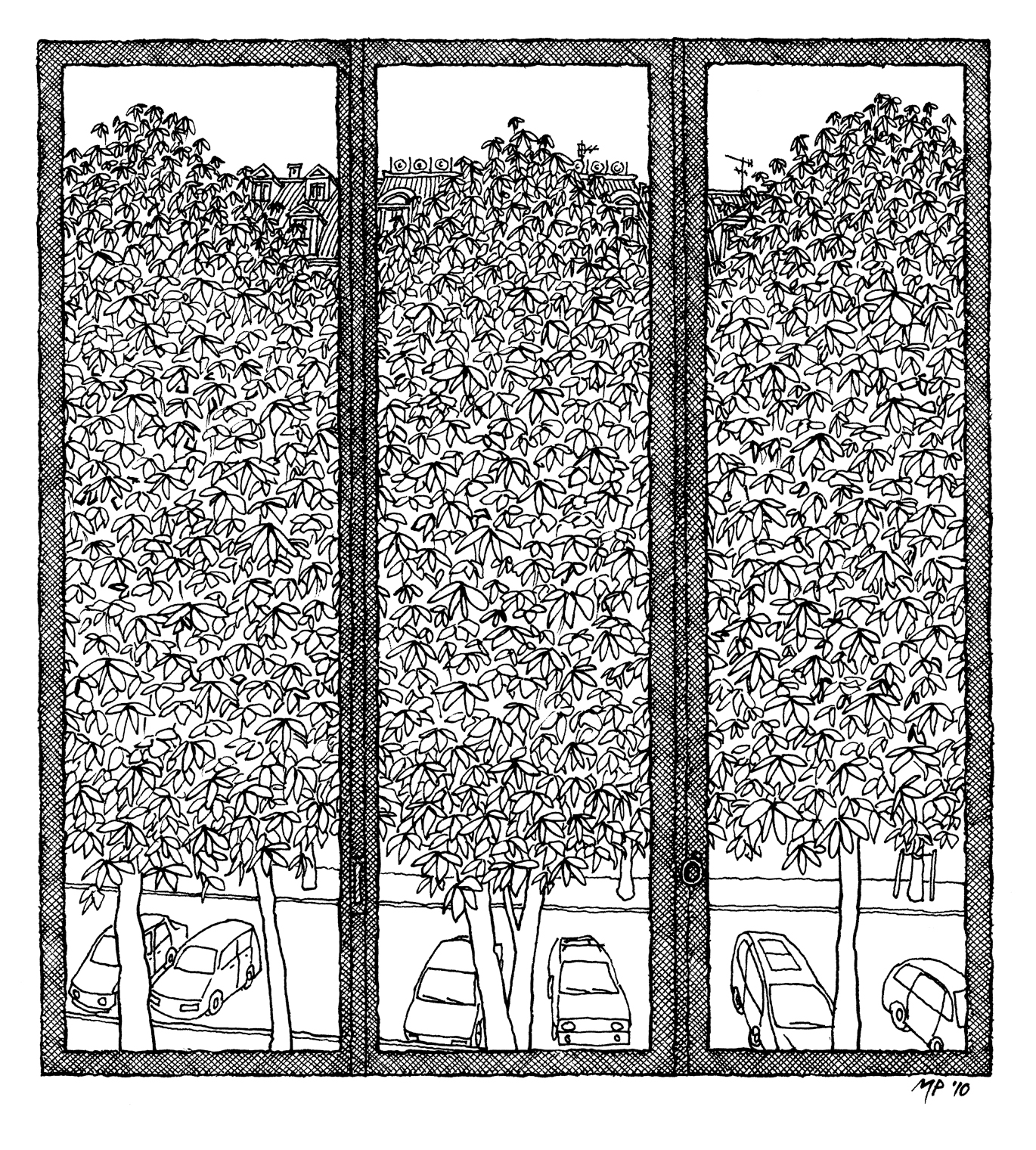

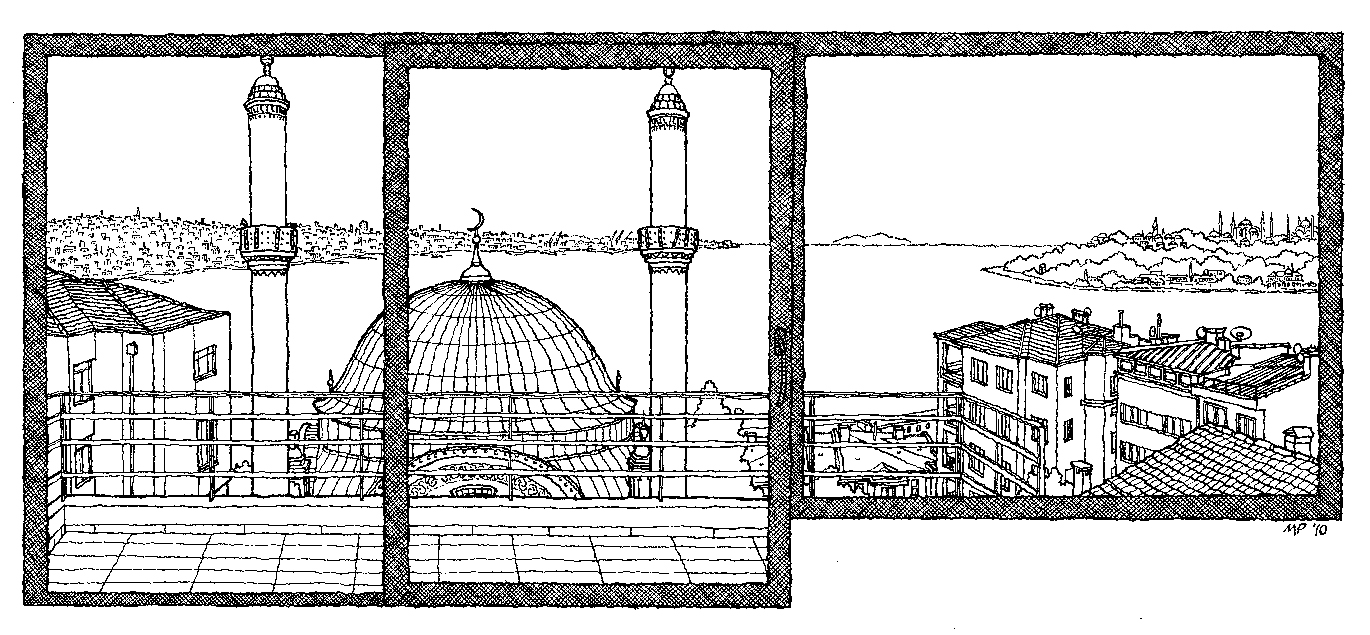

It came after I moved house. I had to leave my apartment in the Upper West Side, and with it the view from my window on 102nd Street. I was filled with real dismay on learning that I would no longer be able to observe that portion of the city visible from its windows. I realized that that particular view constituted the city that was most imprinted in my head, and this made me aware that for many other people the image of their city was shaped by the view from their window. So I began the series of windows and, among them, the windows of writers in the Big Apple and all over the world. It was a logical step to move from drawing the skyline of New York to the images of windows: first the physical, objective city, then the invisible—or rather not visible—one of the latter. If I’d not had access to the minds and imagination of the inhabitants and if I’d not drawn what they see from their windows, I’d have lost a big part of the city, its intimate and incredibly personal side. The view from my apartment in New York—like that of that of everyone who lives there—was unique in the world, different from every other view.

Matteo Pericoli, Italo Calvino

In your exhibition at the Casa dei Libri in Milan the drawings of windows are accompanied by short texts written by their legitimate “owners” or by writers who stand in for them, like Giuseppe Culicchia in the case of Mozart and Bruno Gambarotta in Italo Calvino’s. The same thing happens in your books The City Out My Window (2009) and Un anno alla finestra (2011), devoted to the windows of New York and Turin respectively. Do you think there is a link between drawing and writing?

Certainly, especially with line drawing. This is the kind that gives greater emphasis to the lines. If you’re able to identify all the lines of a drawing, it is possible to make out distinctly what the artist was observing and thinking. The line drawing is a powerful mirror of the author’s intentions. Unlike the sketch, which entails getting down on the paper everything you see, at the root of the drawing there is a rigorous process of selection, a synthesis of the reality around you. This is where I see the link with the word: the draftsman is like a writer who has to choose the right words to convey effectively what he wants to express. Steinberg was, in my view, the greatest writer with lines who ever existed. Drawing aspires to the word and communication. You can’t make a hieroglyph with a sketch: to indicate openly what you want to convey you need lines. My relationship with writing has strengthened in the last few years. Now I teach architecture to students of creative writing at the Scuola Holden in Turin and next year, in 2013, I will hold the same workshop of “literary architecture” at Columbia University in New York. There is an incredible affinity between fiction and architectural design. If you take the words away from a novel or a story, what is left? A structure, that needs to be planned in advance or can be discovered a posteriori. It is no accident that many architectural metaphors, like that of “standing up,” work with literature too.

Your graphic style, terse and concise, assumes two different aspects in my eyes. On one hand, the black-and-white drawing with a spare, impersonal and rational line, reflecting your training as an architect; on the other, a drawing with visionary and poetic traits, which makes use of color in a way that is not naturalistic—perhaps a legacy of your father Tullio. Not coincidentally, the windows of your apartment in New York first and then of the kitchen of your home in Turin, express, through color, the deep intimacy of the situation portrayed. I’m also thinking of your colored maps, which redraw a new political geography with an extremely refined chromatic sensitivity. What value does color have for you?

When I use color, there is much more uncertainty, as it is a field that I find difficult to master. I’ve never studied anything about drawing, I acquired the necessary technique on my own. While with line and black-and-white drawing everything has a reason and is dictated by a choice, with color I find myself in a realm where there is still a lot to be explored, and this scares me. I’m slightly colorblind, so my perception of color is distorted. Drawing in color takes me back to the past, to my father, to the things that I learned to do when I was a child. I’d say that color strikes different chords, it lies in a zone of creativity that is very uncertain for me. In my pen-and-ink or line drawings, on the contrary, are collected all the obsessions, the rigor and the routine of what is perhaps a more cerebral activity.

What projects do you have in store for the future?

I’m continuing the series of windows for the Paris Review. Another book of drawings of the windows of writers from all over the world, entitled Windows on the World, is scheduled for publication in 2014. Also in the pipeline is a project with the writer Colum McCann, a sort of ping-pong game in which one of my drawings with 250 lines will be followed by a 250-word-long text of his, and so on 25 times. An experiment aimed at understanding fully the relationship between word and line.

And an “unfurled” Milan?

It’s years that I’ve been away from Milan and the radical changes in urban planning that have been taking place recently represent an interesting novelty for me. Let’s say I’m trying to keep abreast of what’s going on. I’m very curious about what Milan will become. In other words, never say never!

Matteo Pericoli, Orhan Pamuk

Matteo Pericoli, Gay Talese

Matteo Pericoli, Nadine Gordimer

Matteo Pericoli, Cesare Pavese

Matteo Pericoli, Achille Varzi

Exhibition at the Casa dei Libri in Milan.

Photo: Orsola Giunta

Exhibition at the Casa dei Libri in Milan.

Photo: Orsola Giunta

Matteo Pericoli, Map of Africa, 2009, watercolor on paper, for the cover of July 5, special issue of La Stampa dedicated to Africa.

Matteo Pericoli. Photo: Maurizio Michelini