18 January 2018

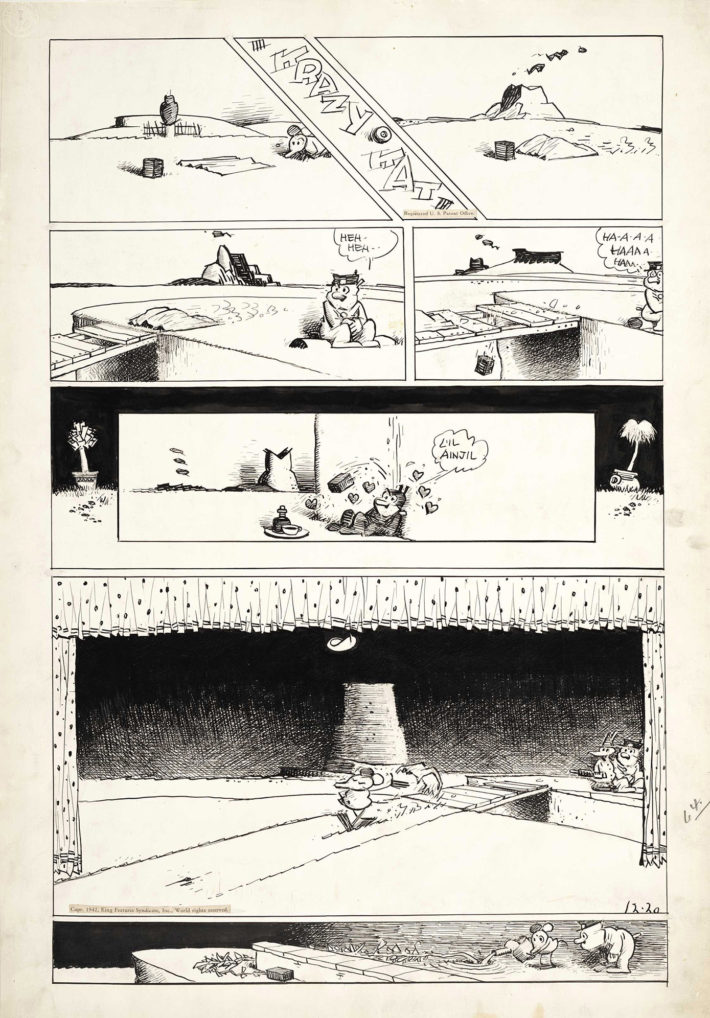

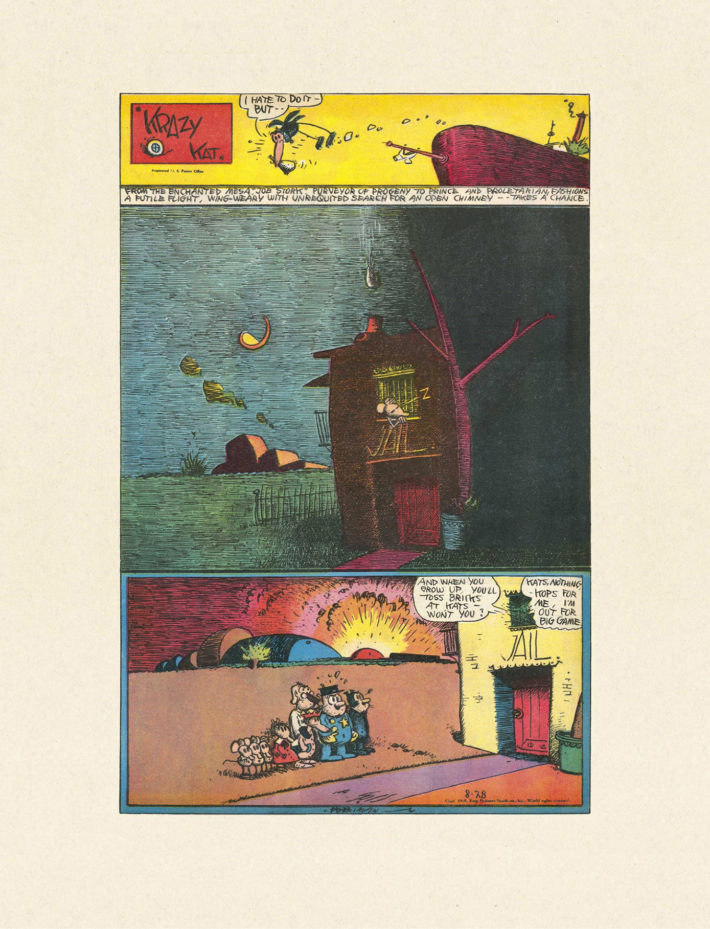

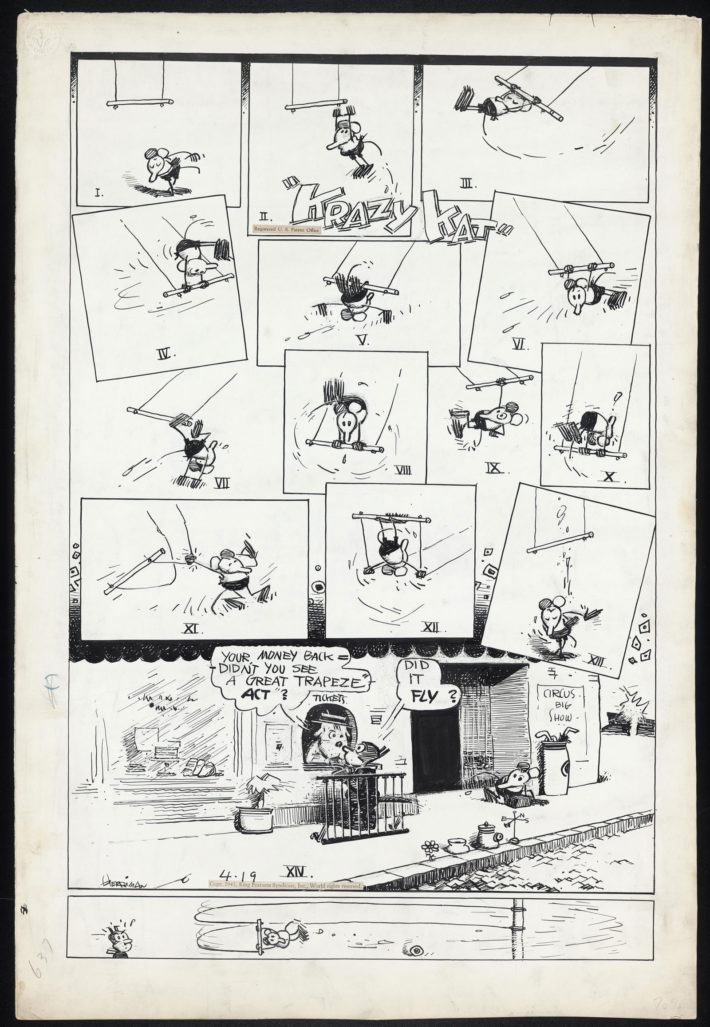

The setting is surreal: Coconino County in the Arizona desert, painted in an almost minimalist manner. The fauna and the flora are pared to the bone, caricaturized. Every so often a rock of bizarre shape, a tiny church, an almost pocket-size hospital, a prison, appears out of nowhere. The characters, a cat and a mouse bound by what is clearly a love-hate relationship, and a police dog who observes what goes on between them, speak a strange hybrid argot, a mix of English, Spanish and Afro-American slang.

If we were to choose a panel at random from Krazy Kat, the comic strip to which the public was introduced for the first time by George Herriman in 1910, we might think we were faced with a conundrum. The subject can be summed up in one sentence: there’s a mouse throwing a brick at a cat. That’s all. Nothing else. Clearly, a mere trifle when the two little animals made their first appearance in the bottom right-hand corner of The Dingbat Family, over a century ago. But that gag was to evolve, for Herriman, into the work of a lifetime: first as a daily strip and then as a Sunday one, carried by the papers of the publishing magnate William Randolph Hearst until 1944.

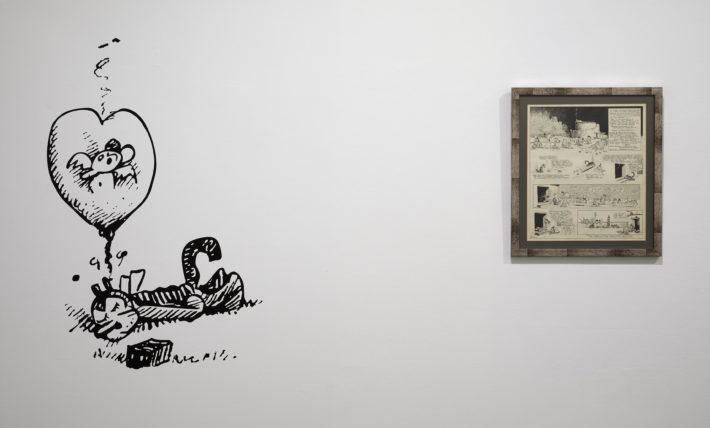

It is against the background of an art, that of the comic strip, which is playing an ever more central role on the European exhibition scene, that we should see the show George Herriman. Krazy Kat es Krazy Kat es Krazy Kat at the Museo Reina Sofia in Madrid (until February 26), probably the most complete ever devoted in Europe to the figure of Herriman, who drew Krazy Kat without a break for thirty years, right up to his death. Interest in the art of the comic strip is growing in Spain, but exhibitions of this kind in this beautiful center of modern and contemporary art can be counted on the fingers of one hand. Authors like Nazario or Antón Patiño have been exceptions.

The exhibition, curated by Rafael García and Brian Walker, comprises around 120 works, from the original drawings to the newspapers of the period in which they were published, drawing attention not just to different versions of Krazy Kat, but also to other minor characters and comic strips created by Herriman: such as Baron Bean, Embarrassing Moments or The Family Upstairs. “Herriman was one of the great artists of the 20th century and one of the most influential,” explains Manuel Borja-Villel, director of the museum. “The surrealist aspect lies in the way in which Krazy reacts to aggression: loving Ignatz even more, responding to hatred with love. Here all the typical social hierarchies are overthrown.”

If in Europe the comic strip was a form of narrative intended for adults, published in journals of political and social satire, in the America of the early years of the 20th century it was aimed at a broader and less sophisticated readership. Herriman represents an industrious and perfect example of the mechanism behind this somewhat ruthless democratization of art: he invented series and characters in double-quick time, outlining their appearance and central traits and then entrusting the stories to other authors, in order to have the time to invent new ones. Krazy Kat—whose gender was deliberately left a mystery—was born like this, as a spinoff, we would say today, after a run-in in the series The Family Upstairs. It was never a great commercial success. On the contrary, as an investment it was probably a failure. But Hearst defended it to the hilt, guaranteeing the strip’s survival in the New York Evening Journal for over three decades.

Today the critics are all agreed: Krazy Kat is an undisputed masterpiece of its genre, the acme of the art of the comic strip. A work able to manipulate the twin universes of language and drawing in such a way as to disrupt both. An existentialist work suited more to bright teenagers and adults—capable of grasping the nuances of the text—than to children, it numbered among its fans Pablo Picasso (who read the strips at Gertrude Stein’s side), Fritz Lang, Frank Capra, T.S. Eliot and even Umberto Eco. In the world of drawing and painting its influence can be discerned in Philip Guston, Kentridge, de Kooning and Fahlström.

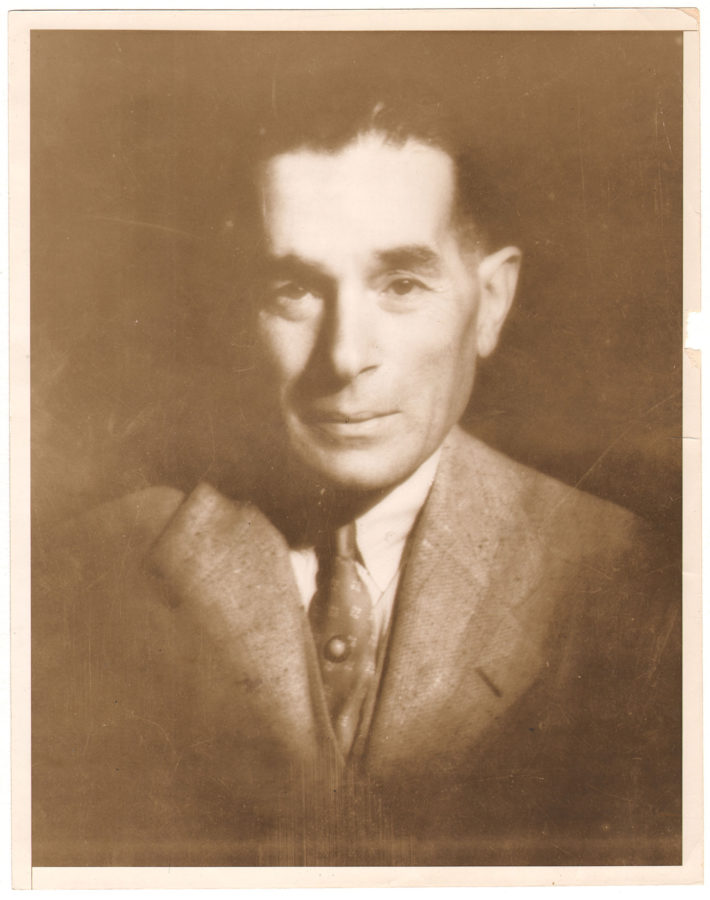

But who was George Joseph Herriman? We know that he was born in New Orleans in 1880, into a Creole family, so that today many label his work as a rare example of a Latin-American comic strip. And yet, for over a century, Herriman was put down in collective memory as a white man. And on his death certificate he was described as Caucasian. It was not until 1971 that someone tracked down his birth certificate, on which he was listed as colored. In other words, Herriman, whose skin was undoubtedly pale, spent his whole life pretending to be white, keeping his short, black and kinky hair well-hidden under the Stetson he unfailingly wore. No explanation has ever been found for this choice: the most likely is that the cartoonist of whom Hearst was so fond feared the prejudices of the day, a racism that might have ruined his career in a South where segregation held sway and lynching was rife.

Seventy years after the last Krazy Kat strip, Herriman’s work remains sui generis, comparable with few other works in this field and capable of winning the approval of an enviable series of intellectuals. Themes of a prodigious limpidity, characters drawn with matchless subtlety, the line and the language unmistakable (to the point where half a century later some might almost have accused a gem like Calvin & Hobbes of plagiarism). Charles Schulz’s Peanuts, Ralph Bakshi’s Fritz the Cat and Art Spiegelman’s Maus could probably never have existed without the trail blazed by Herriman’s creative talent.

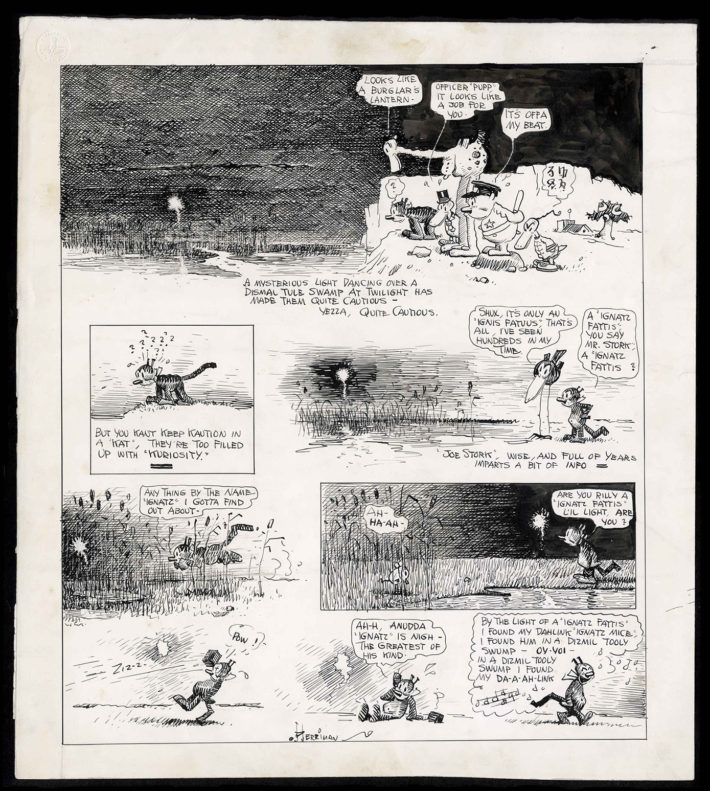

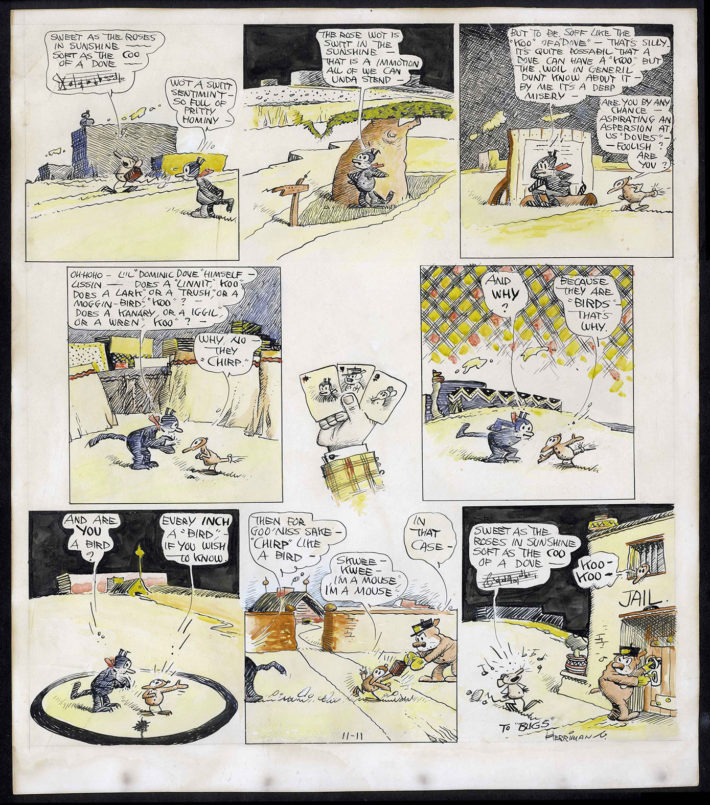

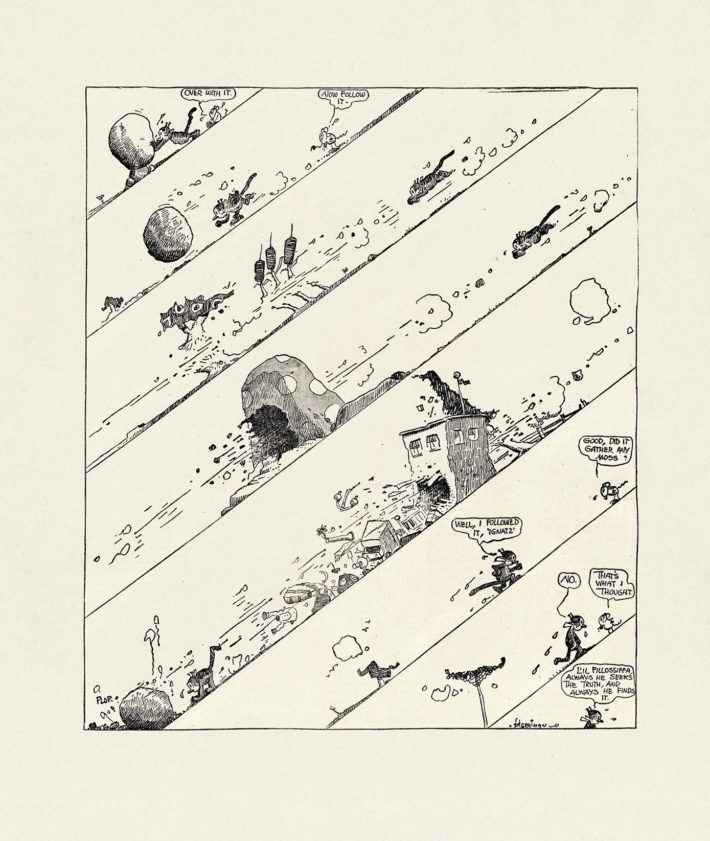

If the idea at the base of Krazy Kat is simple, Herriman always found a way to vary the formula. Sometimes Ignatz actually succeeds in knocking Krazy out with his brick; at others Officer Bull Pupp proves more cunning than Ignatz and manages to put him in jail. And the interventions of the other anthropomorphic animal residents of Coconino County, or forces of nature, occasionally change the dynamics of the game, in unexpected ways. Herriman experimented with language, using alliteration and assonance, and gave the page an original structure, with panels of different shapes and sizes, arranged in whatever way he thought best, without worrying too much about tradition. The visual style of the comic strip is steeped in the culture of the Southwest: with clay-shingled roofs and trees planted in pots with designs that imitate Navajo art. And then, every so often, trappings of the stage appear with spectators, footlights and a small orchestra.

When, toward the second decade of the 20th century, Krazy Kat became the first true comic strip for “grownups” in American history, the world of these cartoons had already taken on the fairly predictable guise which it still has in newspapers today. Historians are wont to attribute a seminal value to Richard Felton Outcault’s The Yellow Kid (1895), but according to the philosopher and literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin it was Herriman who broke “the eternal silence of the universe,” emerging in a sector overflowing with conventions in order to kill them off, one by one. Thus Krazy Kat can be seen as a true exhibit of the modern era, an important text to study, an anticipation of the failures of language in the second half of the 20th century.

If we wished to look for an obstacle to the full enjoyment of Krazy Kat, then perhaps we should mention its repetitiveness, and yet this was deliberate, serving the needs of Herriman’s subtlety. A vivid, complicated and brilliantly conceptual comic strip, it is hard to remember specific situations, lines or images—apart from a few striking phrases. The sense of alienation that permeates this work makes it unique, but prevents it from sticking in the memory, and runs the risk of clouding its undoubted poetic quality, its emotional heart, for a superficial reader.

Krazy Kat makes indeterminacy of gender a key trait of its identity: “I don’t know whether to take unto myself a wife or a husband,” the cat says in one dialogue. Contemporary culture sees, among its protagonists, transgender adolescents, individuals trapped in a body by which they feel betrayed. In this Herriman appears to us today as an oracle. Just as Ignatz’s unmotivated hatred, which recurs cyclically in the stories, mixed up with his sadness and his affection, is relevant to the present day. Everyone, in Krazy Kat, is trying to “pass” for someone else, just like their creator, perhaps, tried to pass for a white man. There are some who do this well, and they are called eclectic. Others do it badly, and are considered crazy.

In other words, Krazy Kat speaks to us of dysphoria, of the pathological alteration of mood. Asking us to accept its characters as reflections of our self, inviting us to explore it; a game in which the author’s imagination, at its most profound, lets the reader inhabit the awareness of others. Even of a comic-strip cat. Who is the craziest then, the kaleidoscopic Kat, or the obsessive-compulsive Ignatz? It has been described as a parable of friendship, a metaphor for democracy, even a single poem lasting for thirty years. According to Chris Ware, Krazy Kat is also a “portrait of America, a self-portrait of Herriman, and the first attempt to paint the full range of human consciousness in the language of the comic strip.”

George Herriman. Krazy Kat es Krazy Kat es Krazy Kat

Curated by Rafael García and Brian Walker

Museo Nacional Centro de Art Reina Sofía, Madrid

October 18, 2017 – February 26, 2018

Photo: Joaquín Cortés/Román Lores.

Photo: Joaquín Cortés/Román Lores.

Photo: Joaquín Cortés/Román Lores.

Photo: Joaquín Cortés/Román Lores.

George Herriman, Krazy Kat, 1937. International Museum of Cartoon Art Collection, The Ohio State University Bully Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum. © King Features Syndicate, Inc. ™ Hearst Holdings, inc., King Features Syndicate Division.

George Herriman, Krazy Kat, 1917. Stoklas Collection, Vienna. © King Features Syndicate, Inc. ™ Hearst Holdings, inc., King Features Syndicate Division.

George Herriman, Krazy Kat, 1926. Collection by Erich Brandmayr. © King Features Syndicate, Inc. ™ Hearst Holdings, inc., King Features Syndicate Division.

George Herriman, Krazy Kat, 1918. San Francisco Academy of Comic Art Collection, The Ohio State University Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum. © King Features Syndicate, Inc. ™ Hearst Holdings, inc., King Features Syndicate Division.

George Herriman, Krazy Kat, 1942. International Museum of Cartoon Art Collection, The Ohio State University Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum. © King Features Syndicate, Inc. ™ Hearst Holdings, inc., King Features Syndicate Division.

George Herriman, Krazy Kat, 1938. Collection by Patrick McDonnel and Karen O’Connell. © King Features Syndicate, Inc. ™ Hearst Holdings, inc., King Features Syndicate Division.

George Herriman, Krazy Kat, 1942 ca. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington D.C. © King Features Syndicate, Inc. ™ Hearst Holdings, inc., King Features Syndicate Division.

George Herriman, 1935 ca.

Collection by Rob Stolzer.