8 May 2014

Interior. Daytime. Milan Malpensa Airport. Planes landing and taking off, tourists at the check-ins and drowsy passengers at the boarding gates. Then all of a sudden, amidst the general monotony, a figure dressed in fuchsia and lime yellow. It is Italo Rota, Milanese architect and flâneur. Born in 1953, he began his career in the seventies in Vittorio Gregotti’s studio and on the editorial staff of Pierluigi Nicolin’s magazine Lotus. In the early eighties he moved to Paris, where he worked on the design of various museum displays: from the Musée d’Orsay to the Centre Pompidou, from the new rooms of the French School in the Louvre’s Cour Carré to the illumination of Notre-Dame. In addition to a series of luxury hotels and bars and clubs scattered all over the world, he designed one of the new symbols of Milanese culture, the Museo del Novecento, opened in 2010. Scientific director of NABA and Domus Academy, he is the author of several books, the most recent of which is Cosmologia Portatile (Quodlibet). Italo Rota has received a number of important awards, including the Medaglia d’Oro all’Architettura Italiana for public spaces and for culture and leisure, the Moses Preservation Award of the New York Landmarks Conservancy and the Grand Prix de l’Urbanisme of the French government. He has recently presented his design for the Kuwait Pavilion at Expo 2015.

I recognized you immediately by the pop colors. Italo Rota, it’d be better to clear this up at once, before beginning the interview. Where does this love of bright colors come from?

My love of color has a peculiar origin. In the first place, it’s because my uncle was in Mauthausen, a place that I’ve always identified with black. Secondly, having always seen brilliant colors in Africa, South America, India, Tibet, color for me is what you see in cities on the caravan route, like in Uzbekistan, where outside there is nothing and inside are hidden marvelous fluorescent colors. Lastly, let’s face it, men have always been prevented by society from taking liberties with color.

Things have changed now, fashion has legitimized colors.

Try going out in the street: nothing has changed. You’ll find color there, if you’re lucky, on tee-shirts. Jil Sander once tried to insert fluorescent colors in her collections, but she got her fingers burnt, economically speaking.

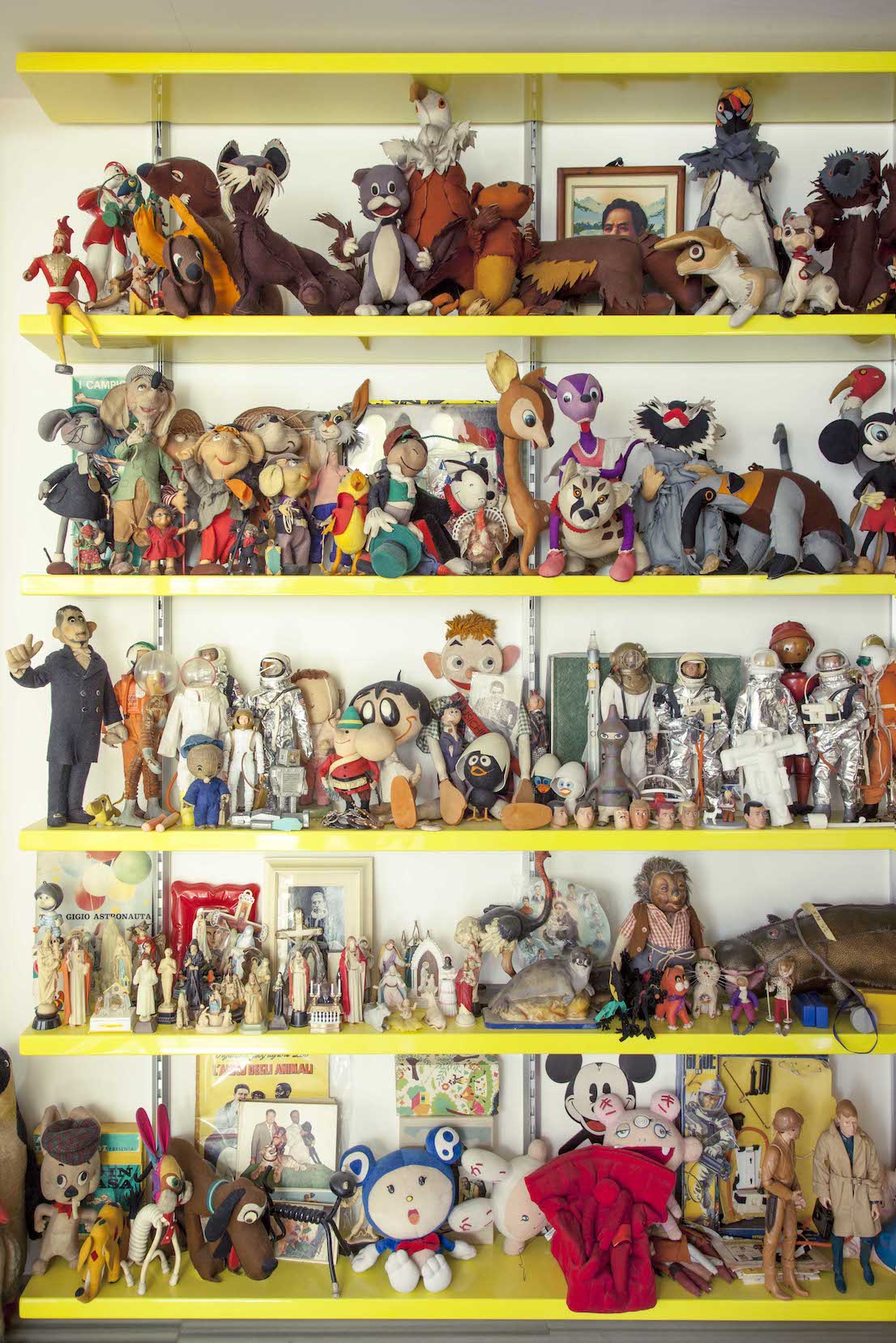

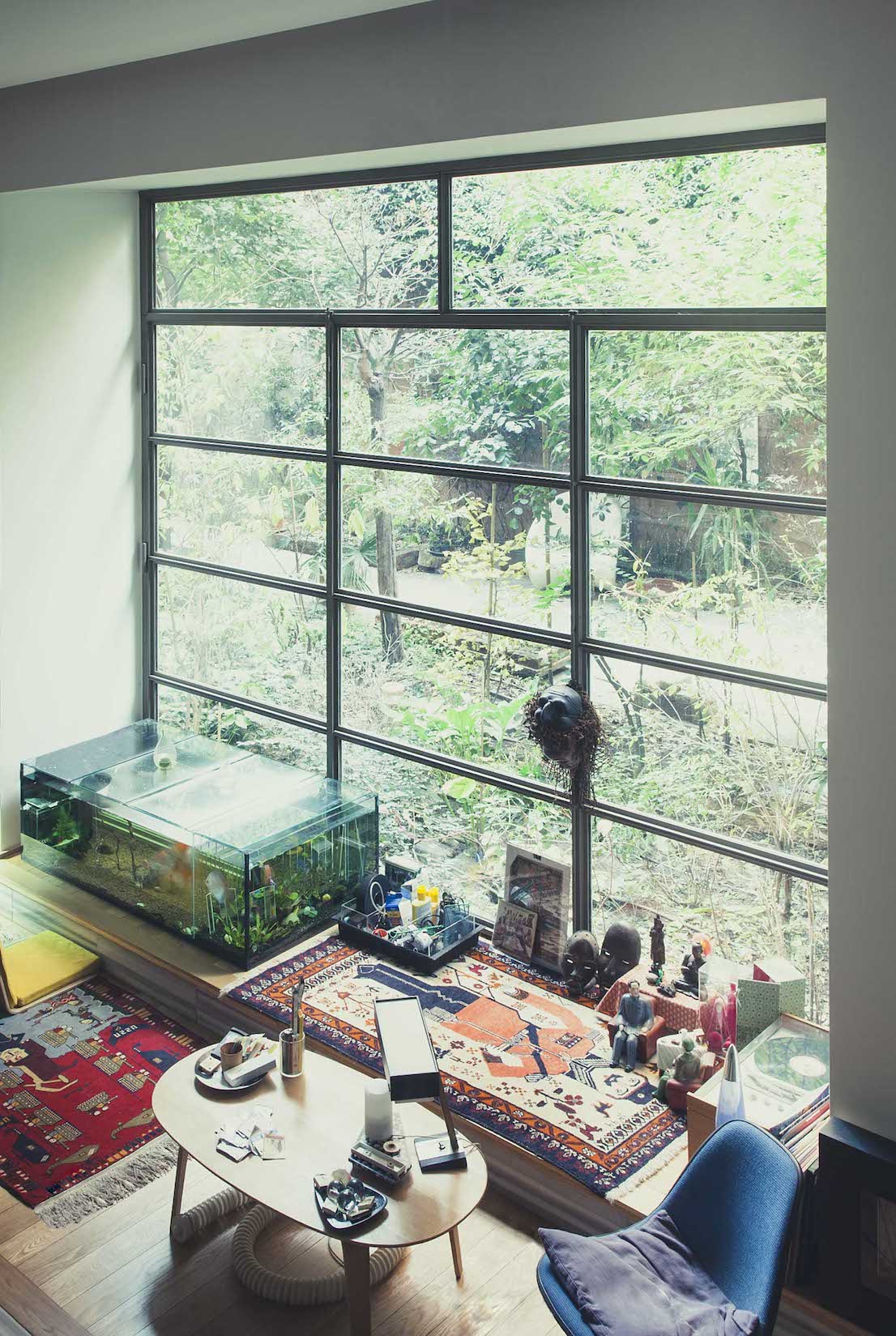

Italo Rota and Margherita Palli’s home.

A definition of fluorescent, please.

Fluorescent color is the kind that emits light. Take a highlighter and use it to draw a line in the middle of two pages of a book. Close the book and then open it again a bit: it will look like a lamp. And then, you know what’s beautiful about this world? That everyone can do what they want, without bothering other people. Careful though: if you don’t please yourself, you can’t please others either. The trick lies in pleasing people with great wisdom.

A definition of wisdom, please.

Wisdom is being serious and having a crazy plan. When I was at the Polytechnic, a professor whose name I can’t remember used to advise his male and female students to shave off their hair and their eyebrows and go out in the street to observe people’s reactions. You need to use your own body as the first territory of architecture.

At this point I’m going to ask you to show me your tattoos.

I haven’t got any, but I’ve a great admiration for both tattooists and tattoos. Just think of the damage done by that book by Adolf Loos, Ornament and Crime. It’s an amazing title that has created its own myth, even if the book is trash that no one has ever read. A bit like “less is more,” two magical little words with which architects try to survive.

You’re exploding a myth for me. Is an architect allowed to refer to Mies van der Rohe in this way?

You see, there’s a little secret in that formula: in order for those two little words to work, you have to put in a few drops of bad taste. Look at the success of Prada, and its genius: there’s always a touch of bad taste in there.

Italo Rota and Margherita Palli’s home.

All right, we can start the interview. What are you doing at the airport with a ticket for Istanbul?

I’m on my way to Kuwait, I’m working on their pavilion for the Expo. I’m happy to do it because it’s a very different country from its neighbors in the Gulf: it’s a democracy where the religion is Islam, but it’s not imposed on anyone.

Why is it easier to meet you in line at a boarding lounge than in the street in Milan?

Traveling is my most natural state. There are many kinds of traveler. I’ve always had the luck to go around the world, and to combine my work with the discovery of a country. It’s real luck, because there’s no better way to visit a country than to experience its everyday life.

How often do you go?

If I can I take a plane every week. I’ve lived much of my life with my feet off the ground. This amuses me greatly, along with the fact that at any instant there are two million people up there in the sky.

You travel a lot, you fly overseas, you know the world, but are there places where you feel more at home as an Italian?

I feel a strong affinity with age-old cultures, like Japan or China. It’s becoming more and more evident: old cultures generate individuals with an edge. Not more intelligent, not wealthier, but ones who are always able to survive. Another aspect is that someone with millennia behind him knows what to offer the world with his past. It’s not for nothing that these are the countries that have put up most resistance to globalization, which in any case is no longer there today. There are only ideas or objects.

Italo Rota and Margherita Palli’s home.

Proof of this is provided by your collection of objets trouvés unearthed around the world.

My objets trouvés are linked to travel and to work, but they’re only there in passing. I don’t keep them jealously for myself. My wife Margherita [Palli, Luca Ronconi’s longtime stage designer, author’s note] and I have given many things to museums, and to friends as well. For me donating is an activity linked to the life cycle, it means you still have energy to exchange. Anyway, collecting and selecting objects is one of the most basic human instincts, as archeology and anthropology can confirm. The earliest graves were identified when a selection of shells was found alongside a skeleton: the love of objects is inherent in the human spirit.

It’s said that you have Yuri Gagarin’s helmet in your collection. Which is the object you love most?

I think love only applies to people. Where objects are concerned we are just talking about accumulation. I fall in love with people, never with things.

Does your work on museums stem from your passion for collections?

No, I started to work on museums by chance, when one summer in the eighties Gae Aulenti and I won the tender for the interior design of the Musée d’Orsay in Paris.

What are your memories of those days?

We were like a couple of drunks, we felt as if we’d won the lottery. Up until then Gae had done four apartments and designed a few beautiful objects, I was graphics editor of Lotus and had taken part in the odd competition. Let’s say that it was my first workshop: in the first project, the d’Orsay envisaged having locomotives alongside the pictures, in a pure socialist spirit. Then the second Socialist government took a step back, but Mitterand, who visited the construction site, was still saying: “But won’t this stone make it look a bit fascist?” In German they call these Banalitäten, banalities, and it shows that even when a politician is intelligent he can’t be knowledgeable about everything.

Italo Rota and Margherita Palli’s home.

Let’s move from Paris to Milan, where you designed the Museo del Novecento at the Arengario, in Piazza Duomo. What should a museum be like, in your view?

There’s no standard typology, every museum has its own collection, its particular location. It all depends on the relationship that a community has with the work, with the works.

What relationship is there today between the work and the community?

I think that the question is in a way no longer relevant. We tend to observe objects as such, assigning them an autonomous value. This is a completely individual process, and goes hand in hand with the fact that people today have a creative life, which is the reason why art in the strict sense has lost its centrality. No one thinks that a contemporary artist can make a difference, in any area of society.

But who is the great artist today?

Today there are collective works to which a name is attached by convention. For example, when you go to see Gravity, one of the best movies in the history of the cinema, you ask: but who is it by? We don’t know, the idea came from the director, Alfonso Cuarón, but behind him there is a host of people responsible for the way it was made and shot. The collectivization of the work is a phenomenon that is going to change architecture too, and we are already coming to the end of a cycle. The period of the so-called starchitect, in fact, has just been a passing phase.

So there is something positive, we are getting rid of the starchitects.

No, we mustn’t make judgments. It’s simply that first we like apples, and then bananas, but the change is radical. I think that in the coming years communities will turn to groups of people to solve a problem, and out of this will come new creative forms that we cannot even imagine today. The beauty is that this will lead to new things, while at present architecture is still there cutting out façades and doing scissor work.

What a depressing description of architecture. Are things really that bad?

They’re not going very well. Because it is still a long way from the future, that is to say it is living through the last gasps of an electromechanical era. In reality, this inertia is partly a consequence of the fact that there has been no progress in construction. It’s true, the materials have improved, but the real problem is increasing efficiency and changing the model of living.

So in reality it’s the human being that should change.

Yes, because there are so many of us that small individual decisions can solve problems. Today we know that communities have a mind, that is to say they’re much better than individuals. What we are seeing nowadays is that people are taking decisions for themselves, with others.

You say that we shouldn’t make judgments, but this seems to be a decidedly positive attitude.

Certainly, look at our relationship with the planet. If we behave badly industry doesn’t make a profit anymore and the economy grinds to a halt. In Milan this year people have left their cars at home and have started to use bicycles, or car-sharing services. Everybody is making better use of their time.

Italo Rota and Margherita Palli’s home.

On the subject of time, your book Cosmologia Portatile [“Portable Cosmology”] has recently been published by Quodlibet. It was written exclusively at night as if it were a book of dreams like Fellini’s or one of Prospero’s twenty-four books…

Fellini is very important for me, in the sense that what many see as a distorted vision to me looks simply like an amplified vision. When you amplify, the things that you know become commodities that you can very easily do without. This happens rarely in architecture, I’m thinking for example of Jean Nouvel, while for Frank O. Gehry or Zaha Hadid the problem is exactly the opposite.

But what point have we reached with architecture?

Architecture has ceased to be forever, or at least to be imagined as lasting forever. I think that today a wise architect, with three eyes instead of two, ought to be happy to know that everything he does has a time limit. Not in the sense that it will stop working at a certain point, but that if something better turns up it will be demolished and either something else will be built in its place or the site will be left empty. I think this is one of the psychological breakthroughs that young architects need to make: to stop thinking about living on through ruins.

Fellini said that he had always dreamed of becoming an adjective when he grew up. What adjective would you like to be, as a grownup, Rotesque or Italorotian?

Let’s say that Fellini could allow himself the luxury. An architect doesn’t have these problems, partly because the cinema speaks directly of the self, while architecture doesn’t. Once the construction is finished, the architect doesn’t matter anymore, for good or ill. Then it’s up to the local people to keep it, if they’re happy with it, or to throw it away, abuse it, modify it.

Speaking of the adjective Felliniesque, did you like The Great Beauty?

A lot at the level of its images, but that film paints a picture of a world that actually exists and that I detest. It is 100 per cent reality, and the film is brilliant because, with the quality of true artists, it succeeds in sublimating it. That said, it’s a world that is my ethical enemy, my social enemy, the obstacle that prevents the younger generation from working, from expressing itself.

On the subject of the younger generation, you are scientific director of the design campus of NABA and Domus Academy, you have taught and you are still contact with the young.

It’s difficult to translate your own experience into teaching material. As a teacher it’s not easy to have a close relationship with the students. It’s a different matter when it comes to designing the school, choosing the teachers, discussing where to go.

Italo Rota and Margherita Palli’s home.

Is it a good idea to teach design to students?

To start with it depends on what you mean by design.

And what you mean by teaching.

Yes, that’s right. I think that today teaching means talking about work, not about the fact that when you finish school you’ll get a job, but that the job you choose is a serious thing that needs to be thought about, to be planned, in order to really do the things you want to do. Everything turns around the passion: you need to be happy with what you’re doing, because without this positive sensation you’re not going to do much. In Italy we have the problem that the young are little inclined to use the future tense.

If that were the only problem.

There are other problems, and how, but the school can still help by preparing the people who in the years to come will be part of the intermediate cycles of creative production, be it the production of the city, an object or the new socioeconomics. And here we are back to the problem of the passion: for someone who has been thinking about picking up a pencil, making a hole, smoothing cement and changing the world with buildings, what pleasure is there in being an architect who does socioeconomics?

What did you want to do when you were a boy?

I played a lot with toy soldiers, I made models, and then at the age of sixteen I started looking for minerals. But basically I’ve always lived with a certain idea of fear. I always started out from an idea, from fear and from the hostile worlds that had to be respected.

Seeing that you often talk about the cinema, I thought you might have wanted to be a director. Would you like to make a movie?

Certainly, in fact I’m trying to get it together. I’ve been doing trials for a while now. It is a film of sex fiction.

In the near future, Expo 2015. How do you imagine Milan?

I have no idea what is going to happen, no one has. In Milan there are some districts that work well, others that don’t. However, I don’t feel the city is in such a bad state, apart from the polluted air. And then life in Milan has never been different from how it is now. I was born there, and it’s always been like that, a relatively friendly city, where homes are open and you can meet people from all over the world. But it has never changed, in part because it doesn’t have the room to do so. Nevertheless, in Milan there are many theaters, many museums and the health service is one of the best in Europe.

You were a councilman in 1994 under the Northern League and Formentini.

I was brought in to solve the problem of garbage and we set up the first civic network online, which was a way of encouraging individuals to produce less garbage. In that period we wrote books on the rights and duties of citizens that everyone received at home.

And what do you think of Giuliano Pisapia and his work for the city?

Pisapia is a decent guy, but I think that like all the people elected in that period and under those conditions he doesn’t know who he was elected by and for what. If I were in his position I would open up more, I’d want to tell people my intentions for the little time that is left to me. There comes a moment when you need to be open to dialogue.

Italo Rota and Margherita Palli’s home.

And Milan is not going to collapse with the World’s Fair?

Of course not. The visitors to Expos are responsible, enterprising people, who won’t go to sleep in the center. They’ll find cheaper solutions and bring their teenage children to see what the world is like.

What do you think of the former mayor of Florence, who is our prime minister today?

Matteo Renzi was predestined for this role. It’s many years that he’s been working on this project and let’s hope he can pull it off. As mayor he devoted a lot of time to Florence. When I say time I mean real time, the time needed to get to know the city and learn its secrets in order to govern it.

Well, this airport interview is over. Today you’re leaving, soon you’ll be coming home again.

No, look, I wouldn’t speak of home. It’s not that I’ve got anything against homes, not at all. In my life I’ve only designed two houses for two people, first of all because I’m always on the move, and secondly because I don’t want to give shape to individual problems.

Who are the two people who you chose to design homes for?

One is a very special house in Paris, the other is Roberto Cavalli’s house. I know how he lives, we are of one mind. It is underground, it is made for one person who has no servants, who consumes almost nothing, who has the luxury of a bit of space and two or three very expensive pieces like the staircase, which cost so much for political reasons.

Perhaps it’s not polite to ask, but how much did it cost?

Half a million euros just for the labor. It’s a political project, the decision of throw money away in order to give craftsmen a living. That’s what Ron Arad and Jasper Morrison keep talking about: insisting on finding someone willing to buy the added value there is in some objects. One of Ron Arad’s chairs contains a thousand euros of steel, but hours and hours of work. On the one hand it’s a subtle form of politics, aimed at preserving the sophistication of thought connected with craftsmanship, and on the other a way to keep these people with golden hands going. A rare, almost unique attitude, which stands out clearly from the usual one.

Italo Rota and Margherita Palli’s home.

Italo Rota and Margherita Palli’s home.

Italo Rota and Margherita Palli’s home.

Italo Rota and Margherita Palli’s home.

Italo Rota and Margherita Palli’s home.

Italo Rota and Margherita Palli’s home.

Italo Rota and Margherita Palli’s home.

Italo Rota and Margherita Palli’s home.

Italo Rota and Margherita Palli’s home.