13 March 2017

We meet Mario Bellini at the exhibition, Italian Beauty, that the Triennale in Milan is devoting to his long, successful and highly industrious career: eight Compassi d’Oro, 25 of his works at the MoMA in New York, an architect of international standing, editor of Domus from 1985 to 1991. Eighty-two years worn with energetic aplomb and many projects still in the drawer. A piece of stage machinery, a gigantic portal-bookcase, introduces us to the world of Bellini’s design, displaying a compendium of his work, with models, furniture, objects and videos inserted in a large red rack. The design of the exhibition display is also by Bellini, who has always worked on the theme of presentation. But the architect doesn’t like to use the term retrospective: “I prefer to call it a prospective, seeing as how I am still looking to the future.”

Mario Bellini. Italian Beauty, Triennale, Milan, 2017. Photo: Gianluca Di Ioia.

Let’s start with the exhibition: a gateway, a square, a gallery—fundamental elements of the Italian city—organize the whole space of the exhibition. How do you approach displaying architecture in a museum?

Back when I was editor of Domus I was already thinking about how to take architecture into museums. The best way to experience it is to go to the place, hear the echo of your footsteps, sniff the air, look at the architecture, touch it, compare it with your own body, with your own scale. A process of familiarization. But, obviously, you can’t always go to the other side of the world. And then the best way to put architecture on show is to film it and project it on a large scale. In a museum. And that’s what I’ve done. We have installed enormous screen-walls—bigger than in a movie theater—that make it possible to see the architecture on a scale of 1:1 and take visitors on a virtual tour of the outside and inside of my buildings scattered all over the world. Paris, Frankfurt, Tokyo, Melbourne. In all the displays I’ve designed, I try to bring a story back to life by getting the exhibits and the works to “speak”: it requires a vast amount of preparation and study: the briefing of the client and the plan underpinning it have to be interpreted and translated into a physical design, one that can be considered a success if the visitor enters, looks and understands.

Mario Bellini Designer, MoMA, New York, 1987. Mario Bellini Archives.

Sixty years of multifaceted work between design and architecture, and a solo exhibition held at the MoMA, in 1987, exactly 30 years before this one at the Triennale.

At the time the MoMA invited me to stage an exhibition on my work as a designer, as it already had 25 of my works in its permanent collection. They told me it was a privilege that had only been offered to Ray and Charles Eames before me. Also at the MoMA, in 1972, I had presented the Kar-a-Sutra, a concept car designed for the historic exhibition Italy: The New Domestic Landscape. I had not set myself the objective of modifying the style, the “lines” of the car, but had asked myself what an automobile really was: so I invented an unconventional “mobile space” that was free and open. It was a step beyond the sedan, and anticipated the idea of the people carrier. It was from just that design that models like the Renault Espace and the Multi-Purpose Vehicle were developed subsequently. Today, now that I’m over eighty, I’m thrilled to make my “debut” in my own city, Milan, with an exhibition that covers my architectural work too. And it’s an immense pleasure to do it at the Triennale, which has been a strong point of reference ever since I graduated from the Polytechnic in 1959. Why Italian Beauty? Beauty has in itself a subversive and redeeming power that we often overlook, perhaps because we Italians are constantly surrounded by it. Our work is an untiring quest for beauty, in the philosophical sense of the term. It is a continuous process of selection and decision-making, in order to imagine, design and realize. The quest for beauty should be unremitting. But it cannot and should not be the only goal of the architect. Who ought always to feel the need for dialogue: with people, with the city, between cultures, between religions. Every new project is like a journey in search of a meaning, of an emotion, and of course of beauty.

Kar-a-Sutra, mobile space, concept car, designed by Mario Bellini for the exhibition Italy: The New Domestic Landscape at the MoMA in New York, 1972. Photo: Valerio Castelli, Centro Kappa.

A decisive turning point came in 1987, leading you to amplify the scale of intervention and design buildings of a considerable urban dimension that were constructed all over the world.

Toward the end of the eighties I started to take part in competitions and won several of them, constructing buildings in Japan, Germany and Australia. Design has always come naturally to me, whether of chairs or buildings: I’ve never had any problem with changing scale. Just like many modern architects, from Le Corbusier to Alvar Aalto, who were always at their ease on different scales. I belong to that Milanese school of architects accustomed to designing objects, furniture, houses, museums, cities. Around the world, I’ve designed the Tokyo Design Center, the Yokohama Business Park, the Risonare Vivre Club Complex at Kobuchisawa, the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, the Natuzzi Americas Showroom in High Point, the Deutsche Bank in Frankfurt and so on.

Tokyo Design Center, Tokyo, 1988-92. Designed by Mario Bellini. Mario Bellini Archives.

Tell us about the project for the Louvre which, besides Pei’s Pyramid, is the other major contemporary intervention in the Parisian museum.

It’s the Department of Islamic Arts, opened in 2012. A project for the French state carried out under the mandate of three presidents very different from one another: Chirac, Sarkozy and Hollande. It was a question of creating a new home for the collection of Islamic arts in one of the Parisian museum’s courtyards, the Cour Visconti, while not only showing respect for two different cultures but also trying to lay out a square as a place in which to hold a peaceful dialogue. Thanks to the use of some experimental high technology we were able to develop a “structural skin” for the roof: floating, layered and innovative, almost a flying carpet, a Berber tent. A light and transparent honeycomb structure made up of a mesh of silver-colored anodized aluminum and another golden mesh. Between these two layers, a double sheet of high-performance glass filters the light and has an insulating function. In the exhibition we chose to show both samples of this material and a spectacular film of the undulating roof of the Louvre shot from above.

New Department of Islamic Arts, Musée du Louvre, Paris, 2005-12. Designed by Mario Bellini with Rudy Ricciotti. Photo: Philippe Ruault.

What have you never designed and would like to?

I’ve never had a change to design wineries and churches. I would really have liked to design a winery. Perhaps one day…

One of your sources of inspiration is Antonello da Messina’s picture of St. Jerome in his study—which is likened to a workplace. What is your idea of the office space?

The office is first of all a group of people who occupy a place: so it is necessary to understand the relationship between them, how these people interact, what is the relationship between the spaces. When you work with colleagues, for instance, you need to have an arrangement of the furniture that is suited to interacting in comfort. So I thought of adding to the rectangular top of the traditional desk a round appendage that would allow people to work together, without corners. I didn’t start out from a merely functional problem, but from the meaning. The solution I found—the Pianeta Ufficio (1974)—was immediately copied by various companies around the world.

Pianeta Ufficio, design by Mario Bellini, 1974. Modular system of office furniture. Photo: Gabriele Basilico.

What relationship have you had with the Postmodern?

I’ve always regarded it with suspicion. I didn’t get involved, just waited for it to pass like a wave. I’ve never fully subscribed to it, although it has probably had an influence on me.

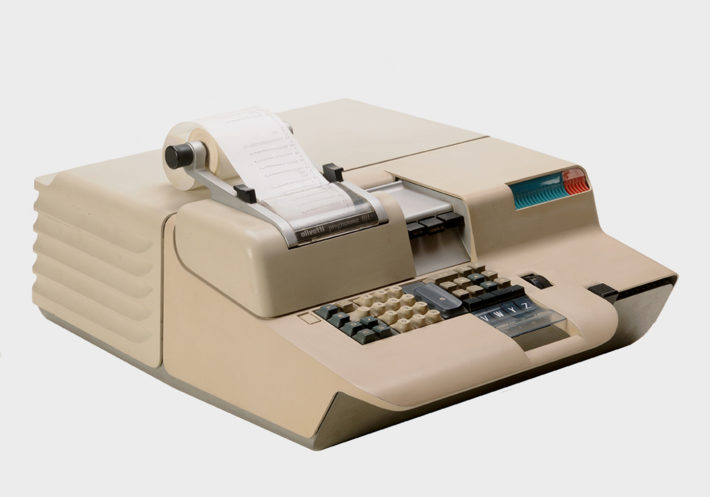

Tell us about your experience with Olivetti and your designs that anticipated the need for portable devices by decades.

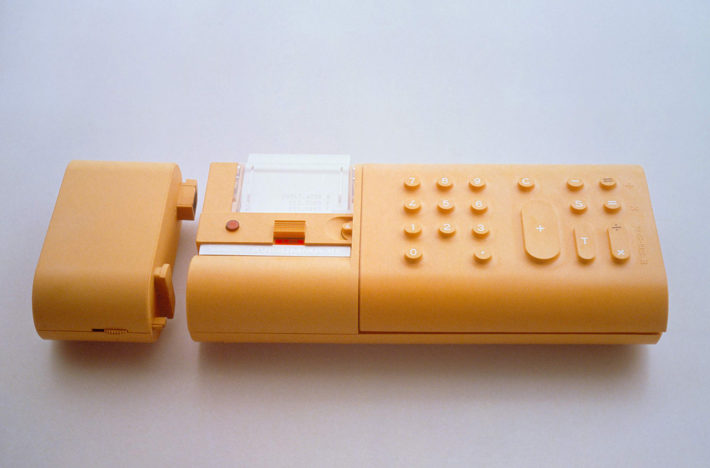

Right from the first personal computer I designed for Olivetti, the P101, I focused on the relationship with the user, on the relationship between the machine and the person. In the design of the Divisumma, the electronic calculator I created for Olivetti in 1973, it was natural to think of it as a “hand-held device,” an object to hold between your fingers. So the first model looked almost like a glove. Working on it, I came up with the idea of a skin: I got rid of the keys, turning them into something like bubbles, very tactile, with a continuous and soft rubber surface. In a way, Divisumma anticipated touch-screen technology.

Steve Jobs came looking for you twice, wanting you to collaborate with Apple.

Jobs got in contact with me after I gave a lecture at the International Design Conference in Aspen, Colorado, in 1981. He came to my studio in Milan twice to persuade me to work for Apple, but I told him in all honesty that I had a special relationship with Olivetti, to which I remained faithful. I’ve never regretted this decision, because at Olivetti I was given freedom and was highly appreciated. I did extremely interesting projects right across the board. Since then I’ve designed around a hundred devices, calculators and computers: from the CMC 7, a magnetic character reader (Compasso d’Oro 1964), to the Quaderno laptop, in 1992. On the occasion of this exhibition, the Triennale has organized an event dedicated to the P101, the first desktop computer in history: it has been made to work by connecting it to the Arduino interface. An exchange between past, present and future.

Divisumma 18, designed by Mario Bellini for Olivetti, 1973. Electronic calculator with rechargeable battery. Photo: Ezio Frea.

What is your personal and professional relationship with technology and computers?

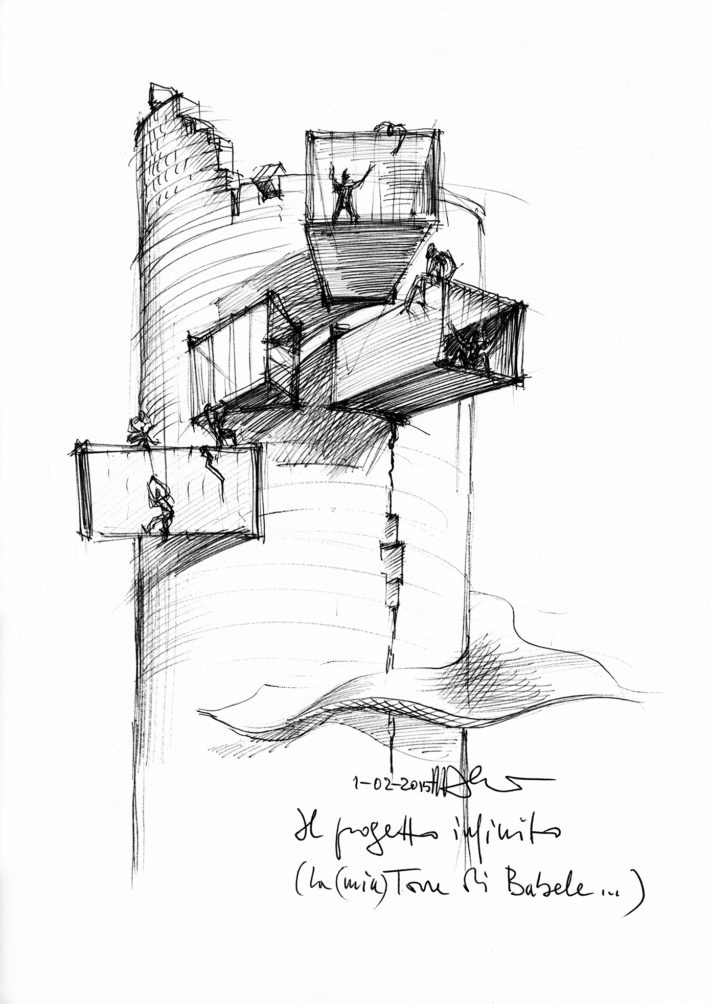

I use technology, I respect it, but I certainly don’t worship it. It’s a tool. In the studio, we have moved from drawing by hand to renderings and perspectives drawn with the computer. We work with programs like SketchUp, which show you quickly what a project looks like in 3D. To invent something, however, I start with a sketch, getting the idea down on paper, as if in a ritual. It’s an individual way of working, one that is completed by teamwork. It’s like an exploration, where I choose the road, stop and set off again, eventually arriving at the final design.

Which do use more to draw, the pen or the pencil? Do you have a fetish about these implements, like many architects?

I can work with anything: fountain pen, biro, pencil, crayon, pastel. I use a lot of shading when I draw: biro is a cold medium, but I like to use it quickly, producing what are almost engravings. What counts is the brain, the special flow that passes from the brain to the hand.

CAB Lounge, designed by Mario Bellini, 2015. Sketch. Mario Bellini Archives.

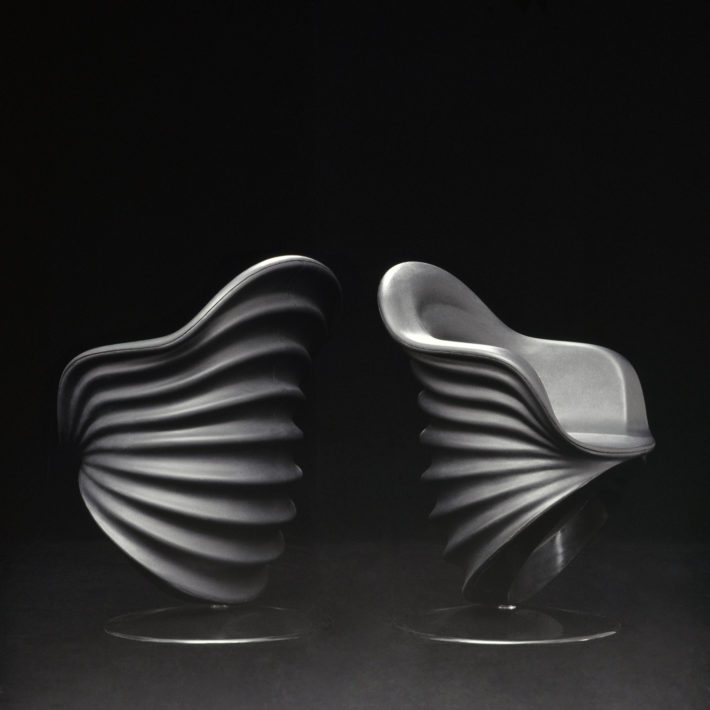

Let’s move onto the design of furniture, of chairs, padded and otherwise. You started to work for C&B (Cassina & Busnelli, later B&B Italia), in the sixties, at a very interesting time for the company: alongside joinery, it had begun to work with resins and expanded polyurethane, allowing it to create not just different kinds of furniture, but new relations with the objects and spaces of the home.

In those years, C&B asked me to design a padded chair. It had to be a soft, rounded object with cushions. So I decided to make a sort of bag closed with a zipper and filled with balls of polystyrene, goose feathers and bits of expanded polyurethane foam. This was in 1972. Out of it came the series of padded chairs and couches called Le Bambole, awarded the Compasso d’Oro in 1979. It was the start of a very successful period of chairs, couches and chaise-longues. The advertising campaigns with Oliviero Toscani’s photographs of the model Donna Jordan were memorable too. In the exhibition at the Triennale I didn’t want to show just the furniture, but also what it looks like inside, how a couch functions on the inside. So we cut a section through it, revealing the innards, the stuffing. For the display I chose to use mirrors all along the exhibition gallery, to make it seem larger and to reveal the back of the objects too, the part behind. The effect of depth that a mirror can create is interesting. It’s the trick I like most: an absence that doubles the presence. Another of my favorite projects—owing to the close link between design and handicraft—is the Forte Rosso bench (1985), carved by hand out of Agra red sandstone. Imagine the shock of a real industrial designer suddenly set free of any technological and production constraint. A bit like asking the player of an electronic organ to pick up a Stradivarius. The Cooper Hewitt Museum in New York had invited five architects to visit craftsmen in India, to carry out a project focused on their manual skill, as a heritage to be handed down. So I designed a bench, making a polystyrene model in the studio on a 1:1 scale, and then sent it to India, where this craftsman sculpted it with a hammer and chisel out of Agra red sandstone. It was a unique experience designing a couch to be constructed with nothing but the hands, a hammer and materials that have been in use for millennia.

Le Bambole, range of padded chairs and couches, designed by Mario Bellini for C&B Italia, 1972. Compasso d’Oro in 1979. Advertising campaign by Oliviero Toscani with the model Donna Jordan. Photo: Oliviero Toscani.

In the exhibition there is also a long section of pictures that explain your design philosophy.

They are the images I use when I give lectures around the world and they sum up my work very well. They are sequences of pictures, arranged two by two, for comparison: works of art, references to the animal and plant world, elements of cultural anthropology, forms, sources of inspiration and faces. For example, Tutankhamun’s chair, which is 3,000 years old, is not very different from the chairs of today, because people are still the same, they sit in the same way. It’s an extraordinary object, not just a functional one: it’s an ornament used in human sacred rituals, an archetype of the chairs of our time.

Mario Bellini in Japan with his Zeiss Hologon camera, 1972. Mario Bellini Archives.

Mario Bellini traveler and photographic reporter: tell us something about your visits to Japan, to the United States.

An extraordinary country, Japan. I’ve been there 130 times. I’ve made a thorough study of its ancient culture, the value it assigns to materials, its philosophy, architecture, religions. I wanted to get to know it in depth, in order to be able to work there. I’ve been fortunate enough to do a number of projects there, in which they have always asked me for references to Italian culture. For instance, in the Risonare Vivre Complex (1989-92) the resort was laid out like a village in Italy with its own streets, houses, swimming pool and hotel. I’ve always taken a lot of photographs on my journeys. In the summer of 1972, after the exhibition at the MoMA, I crossed the United States from coast to coast, taking pictures that have been collected in the book Mario Bellini. USA 1972.

“We traveled in a large minibus,” recalls Marco Romano in the exhibition catalogue, “with a roof that could be opened like a boat, an L-shaped couch facing the side door and another couch next to the driver—adaptations of Le Bambole—so that he looked ahead, while the others changed places, consulted guidebooks and maps, read, played dice, sunbathed. […] Traveling with Mario was a delight, because everything became a subject of curiosity, every meal a moment of experimentation, every building an architectural investigation, every campsite the image of a landscape.”

Journey in the USA, photograph of the Playboy Mansion by Mario Bellini, 1972. Mario Bellini Archives.

What is Mario Bellini’s library like? How do you organize and classify your books?

It’s a bookcase 9 meters high, which also serves as a staircase: from the ground floor to the second floor. I pass through it several times a day and now and then I stop and choose a book. I’ve tried classifying the books in various ways: literature divided up by country, then in alphabetical order; history, divided up by period; art, by subject and again in alphabetical order. Then, every so often, I turn everything upside down. I’m an avid reader, I’m very fond of Simenon’s novels, more than his detective stories. I also read books on history and contemporary poetry—especially German and French—in the original. I think I’m one of the few who have read the three weighty volumes of Mozart’s letters: I was intrigued by the fact that he never mentioned the places he had passed through, even when they were as unique as Venice.

We move, at this point, to the heart of the exhibition, the so-called Wunderkammer: an intimate and personal assortment of objects of sentimental value, photographs, enthusiasms and collections. The guiding thread of this section is provided by the architect’s hands, photographed from close-up, holding a violin, a photograph, a pencil. Passionately fond of classical music (Wagner, Mozart), but also of jazz and opera, Bellini has put on show some pieces from his personal collection: a dish made by Lucio Fontana, a portrait of Bertolucci, Hasselblad lenses, an Issey Miyake jacket, the set of DVDs of Heimat, Gio Ponti’s ice bucket. And a sheet of paper and a pencil, his instruments of choice. Finally, the paintings: from the magic realism of Mario Broglio to an emblematic picture by Mario Sironi, from 1922: The Architect, with a pair of compasses in his hand and a column and a classical tympanum behind him. But he claims not to be a true collector: “I’m just someone who loves music, musical instruments and books. And many objects and pieces of furniture not designed by me. I’m simply very curious.”

Mario Bellini. Italian Beauty

Curated by Deyan Sudjic, Ermanno Ranzani (architecture) and Marco Sammicheli (design)

Triennale, Milan

January 19-March 19, 2017

Mario Bellini. Italian Beauty, Triennale, Milan, 2017. Photo: Gianluca Di Ioia.

Mario Bellini. Italian Beauty, Triennale, Milan, 2017. Photo: Gianluca Di Ioia.

Mario Bellini. Italian Beauty, Triennale, Milan, 2017. Photo: Gianluca Di Ioia.

Mario Bellini. Italian Beauty, Triennale, Milan, 2017. Photo: Gianluca Di Ioia.

Mario Bellini. Italian Beauty, Triennale, Milan, 2017. Photo: Gianluca Di Ioia.

Mario Bellini. Italian Beauty, Triennale, Milan, 2017. Photo: Gianluca Di Ioia.

Programma 101, designed by Mario Bellini, Olivetti, 1965. First desktop computer. Photo: Museo Tecnologicamente, Ivrea.

CAB Lounge, design by Mario Bellini for Cassina, 2015. Photo: Cassina.

CAB 412, design by Mario Bellini for Cassina, 1977. Mario Bellini Archives.

Teneride, designed by Mario Bellini for Cassina, 1970. Prototype of office chair. Photo: Falchi & Salvador.

GA 45 POP, designed by Mario Bellini for Minerva/Grundig, 1968. Portable automatic record player. Photo: Alberto Fioravanti.

The Tower of Babel, sketch, 2015. Mario Bellini Archives.

The White Space of the Architect, sketch, 2015. Mario Bellini Archives.

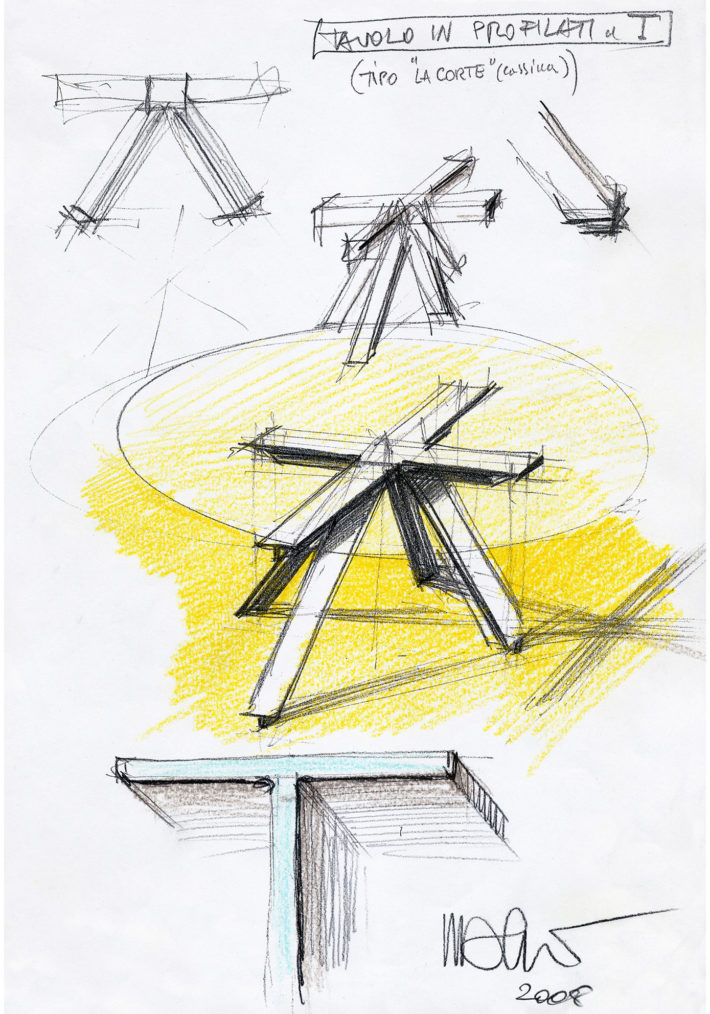

Study sketch for T-shaped table, 2008. Mario Bellini Archives.

Mario Bellini, self-portrait, India ink, 1952. Mario Bellini Archives.