26 July 2013

In response to great demand, we have decided to publish on our site the long and extraordinary interviews that appeared in the print magazine from 2009 to 2011. Forty gripping conversations with the protagonists of contemporary art, design and architecture. Once a week, an appointment not to be missed. A real treat. Today it’s Rossella Biscotti’s turn.

Klat #04, fall 2010.

“I’m interested in the traces of history: documents, films, photographs. They offer another vision of reality. Only when these images are interpreted, decoded and shared publicly with others do they develop new meanings. My works explore the gap between history and its interpretation, between experience and its archiving,” Rossella Biscotti has written of herself. One of the most admired of the latest generation of Italian artists, she is engaged in probing – with videos, films, installations and sculptures – the theme of memory, its articulations and endless lapses. As is clear from this long chat, where history and the story, in hiding or shared, make their appearance many times.

Rossella Biscotti, Everything is somehow related to everything else, yet the whole is terrifyingly unstable, 2008. Courtesy: Prometeogallery, Milan/Lucca.

Let’s start from the beginning, if that’s okay with you? Where were you born, what was your family like, and where did you study?

I was born in Molfetta, in Puglia, in 1978, into what I think I can call a normal family. I studied art in High School, and then attended the Academy of Fine Arts in Naples until 2001, specializing in stage design. My studies did not have a fundamental influence on me, but Naples did. The end of the nineties was a lively time: in addition to the presence of historic galleries like Lia Rumma’s and places like the Fondazione Morra, there were some very young people who were beginning to work in the field: Paola Guadagnino and Marco Altavilla of T293, Gigiotto del Vecchio, Giangi Fonti… A very fine and positive moment. We grew up in a climate of experimentation, in a laboratory. Naples has also been an important city from the social and urbanistic point of view, it has given me a great deal of inspiration. From there I went to Rotterdam, a move that took place almost by chance, as a result of my contact with Cricca Gang, a Dutch artists’ collective run by Patricia Pulles. It was she who advised me to apply for a residence in her country. I left in 2004 and I’ve been there ever since.

How did you spend the first few years in the Netherlands?

Working. I started with five to six months’ residence at the Foundation B.a.d. in Rotterdam, an organization born out of a spontaneous initiative on the part of some artists (the occupation of a building) that has been given a formal structure over the course of time. In 2005 I was invited by the SMART Project Space in Amsterdam to take part in a joint exhibition entitled ADAM, with around thirty site-specific projects on the theme of the sociopolitical conditions of the city. I spent another five or six months there, often going back to Rotterdam. In any case, my stays in the Netherlands have always been interrupted by trips abroad: to New York, Berlin, Rome.

You said that your training at the academy has not had much weight. Do you consider yourself self-taught?

Almost, yes. I attended the course of the Fondazione Antonio Ratti with Ilya Kabakov. And now that I’m doing my first year at the Rijksakademie I don’t really know what to call myself.

When did you start using video? Was it a premeditated choice?

No, it was not a rational choice. I made my first videos at the end of 2001 in Spain, at Valencia (where I had gone on an Erasmus exchange program), because somebody had lent me a video camera. They were very simple portraits of people I met and found interesting. They kept still for about fifteen minutes in a situation that was familiar to them, then performed an action that lasted a few seconds, and then the scene started again from the beginning, in a loop. In common they had the fact of not belonging completely to the context: a Dutch truck driver (Rick), a Brazilian woman and an Italian man who were living together (Patricia and Antonio) and an Argentine (Cesar), my first portrait. Notwithstanding my technical inexperience, looking at that work today still moves me: in Argentina there was a terrible economic crisis at the time and Cesar sang a song by Charly García, Inconsciente colectivo, and then exited from the scene. There was no script, just a few indications given at the last minute, so the videos became moments of discovery. Rick, for example, a big man who kept a mountain of toys in a room for his son, whom he didn’t manage to see very often, in the end hid himself under a barricade of toys, like a child.

Rossella Biscotti, La cinematografia è l’arma più forte, 2007. Courtesy: Prometeogallery, Milan/Lucca.

What was your starting point? Did those subjects interest you even from a social or sociological viewpoint?

I started out from the individual for sure. In those videos you have no background information on the story or the origin of the protagonists, and the possibility of developing more levels of interpretation is limited. The fifteen minutes of silence at the beginning create a strange interaction between the viewer and the motionless person that appears in front of him. I wanted to create a certain abstraction, to freeze reality in order to suggest a different kind of observation. In the same period I had also made a series of videos that I have never shown, entitled Osservazioni con camera fissa (“Observations with a Fixed Camera”, ed), on various situations in the city. The portraits were a later step.

Within a short space of time you began to carry out projects in which the “Italian” connotation, whether geographical, cultural or historical, assumed a decisive weight.

Every work is a piece in the puzzle, the fruit of a particular line of aesthetic research. I don’t have a well-defined program and I don’t like to repeat myself. Of course, reflection on the theme of the Italian cultural identity is one of the interests that I pursue. In videos like L’Italia è una Repubblica fondata sul lavoro (“Italy Is a Republic Founded on Work”, 2004, ed) or Muctar (2003) a social situation is depicted, but there is also a subtle aesthetic identity, which takes as its point of reference that cinema of Antonioni which I think is by now part of our way of representing things and representing ourselves. In Muctar we see two Russian immigrants speaking in their own language, against the backdrop of a Neapolitan landscape that is at once marine and industrial – the same alienation from the context, the same estrangement as in the earlier portraits. In L’Italia è una Repubblica fondata sul lavoro, the theme is not handled in didactic terms, but I try to create a series of surreal situations, between the documentary and the mise-en-scène, in which the idea of the work is detached from that of a mere production and moves toward a playful action, toward Huizinga’s Homo Ludens, the utopias of Constant.

One current of your work carefully reconstructs fragments of the Fascist period.

My exploration of history started out from La cinematografia è l’arma più forte (“Cinema Is the Most Powerful Weapon”, ed) of 2003, created for the Fondazione Adriano Olivetti in Rome. An inscription on a wall, a mural that was intended to refer to the history of Fascism from an aesthetic and conceptual point of view. An intense work, a harbinger of others that I realized later, like Shooting on the Dam (2005). Such a direct reference was shocking even for me, and it still is now: in Italy, with Berlusconi’s domination of the media, that word “cinema” takes on another meaning and in any case traces a history, indicates an origin.

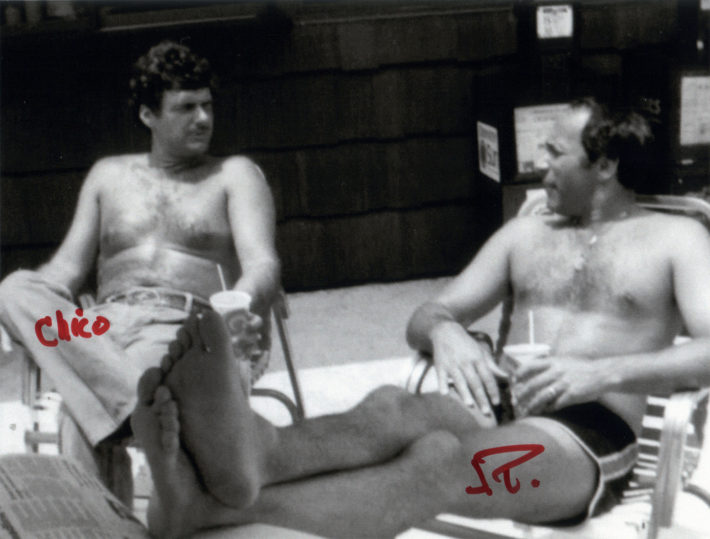

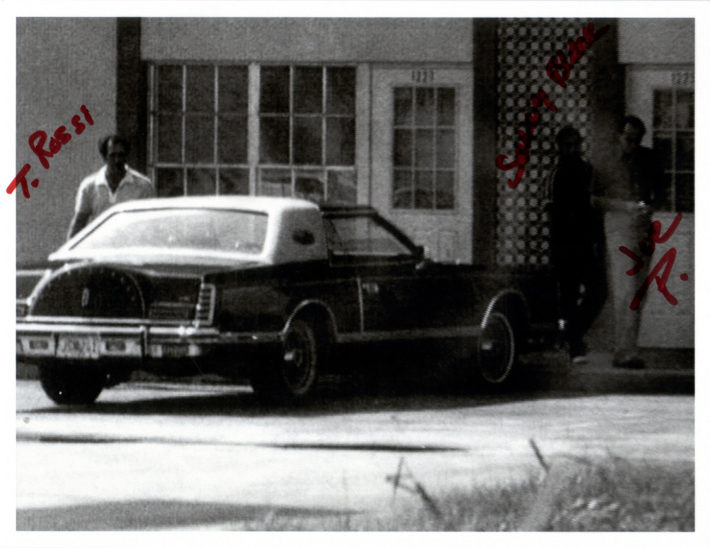

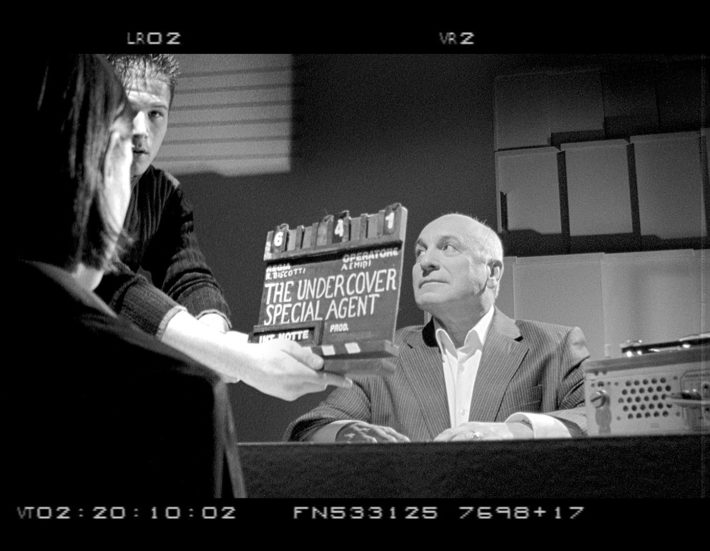

Rossella Biscotti, The Undercover Man, 2008. Courtesy: Prometeogallery, Milan/Lucca.

How immediately recognizable do you think the “source” of that work is? How many people know who invented the slogan “Cinema is the most powerful weapon”? Awareness of history cannot always be taken for granted, especially in our country.

Often there is an almost empirical, immediate recognition. With a project like Le teste in oggetto (“The Heads in Question”, ed), in which I discovered and put on display five monumental bronze heads of Mussolini and King Victor Emanuel III that had been stored at the EUR, the historical origin is spectacularly obvious. But what I’m referring to is a certain aesthetic, so strong as to be recognized and recognizable. After that, certainly, there is a further level of meaning that depends on the personal culture of the viewer. And then yet another, fairly difficult one, that comes into play only if you know where that image or quote comes from. I was curious to try out that slogan because it was utilized a lot in Rome and is still very present. It’s such a stratified city that it seems to absorb everything, but I believe that people have the capacity to recognize what is Fascist.

Luce newsreels from the Fascist era are often shown on television. Initially, they were accompanied by a voiceover that established a historical distance and offered a judgment a posteriori, whereas now they are presented just as they were originally: they give me the impression of a certain ambiguity, as if their propagandistic value was emerging again, above and beyond the documentary aspect.

Even works like La cinematografia or Le teste, which propose materials of the time directly, are ambiguous for me. What I’m trying to do is open a discussion, turn it into a workshop: I’m interested in what goes on around the project, what sort of reaction and participation is triggered by the intervention. I look at these works as a kind of performance, because they interest me only when I’m in the midst of an audience, among people – the relational aspect is very important for me. Now that I think about it, it’s no accident that I presented the two projects in private settings like the Fondazione Olivetti and the Nomas Foundation. I don’t know if it would have been possible to do it in a museum. That might have made the whole thing more problematic, equating my position with that of the institution and undermining the ambiguity I was speaking of before.

In the fall though you’ll be working at the MAXXI, where you’re one of the four finalists for the Premio Italia Arte Contemporanea.

Yes, and I imagine it’s going to be a bit difficult, because when your relations with the public enter a museum they are modified. I would like to work, from various points of you, on the history of architecture, which I think is the prime subject of the MAXXI. If I can, I’d like to present a project on which I’ve been working for a long time, on the bunker in the Foro Italico. It was created in the mid-thirties as a jewel of modernist architecture (originally it was called the Casa della Balilla Sperimentale, then the Casa delle Armi nel Foro Mussolini and the Accademia della Scherma, or Fencing Academy). Designed by Luigi Moretti, it was forgotten and then adapted for a different use in the eighties. A story and a building that I’ve been following since 2006 and know in all its details.

Why that place in particular?

I came across it in the course of a photographic study of Fascist architecture that I was conducting with Kevin van Braak. An investigation that started out from Rome, the EUR and the Foro Italico, and that took us to the sea camps on the Adriatic and in Versilia.

Rossella Biscotti, The Undercover Man, 2008. Courtesy: Prometeogallery, Milan/Lucca.

In the same period you made a video, Il ripristino della vasca vuota (“The Restoration of the Empty Pool,” 2006, ed), on the swimming pool of the Foro Italico.

Yes. I wanted to record the neutral, surreal relationship that exists between that place laden with history and rhetoric and the people who for twenty years have had the contract for its maintenance. Every September the pool is emptied, cleaned and filled again. In the video you see them wandering around and making some gestures, not doing anything really practical: the objective for me was to set up an encounter with the space, to make the presence of history felt through the grandeur of the setting. What you see is dreadful: mosaics cleaned with acid, fumes rising from the floor. But there is no moralistic intent or condemnation: it simply depicts a routine activity.

The way people think about restoration has changed. In 1963, with his Theory of Restoration, Cesare Brandi argued that it “consists of the methodological moment in which the work of art is recognized, in its physical being, and in its dual aesthetic and historical nature, in view of its transmission to the future.” In other words, if you don’t recognize a work as such, if you don’t set it in an aesthetic and an era, you can’t restore it. At the most you repair it. Right through the seventies restorers practiced neutral retouching, which made the lacunae due to the passage of time clearly visible. Then, seeing that the effect was too Calvinist, “conceptual” and unattractive, they have gradually gone back to mimetic restoration. The preferred effect is the “as new,” which makes the traces of the past vanish and brings the work back to a hypothetical original state. Or an eternal present.

I find this reflection interesting. Over the years, Moretti’s bunker in the Foro Italico has been reappraised as a rationalist masterpiece, while the renovation to adapt it to house high-security trials in Rome from the end of the seventies onward has been judged a defacement: trials ranging from the Moro case to the attempt on the pope’s life, from April 7 to the Banda della Magliana. A very burdensome history that we are reminded of every time we see a picture of it: the hall is an incredible work of engineering, with very clear lines and the light entering from the side. Then you see the cages, the place of the court, the seats, the chambers and you remember the years of lead. Soon all this will be thrown away, because the complex is being returned to the CONI (Italian National Olympic Committee), the same organization that maintains the swimming pool in the Foro Italico, to turn it into a museum of sport. There has been a great political controversy, but in the end they decided to carry out a radical restoration of the hall, returning it to its “original splendor.” This moment of transition interests me greatly. Erasing the renovation, however inappropriate it may have been, also means removing the traces of that terrible past which is part of the history of Italy and which has not yet been completely worked through, discussed historically.

Rossella Biscotti, Le teste in oggetto, 2009. Courtesy: Prometeogallery, Milan/Lucca. Photo: Ela Bialkowska.

I was struck by the fact that many students, interviewed after the Italian exam for this year’s school-leaving certificate, said that they had not chosen the essay on Primo Levi because it was “not on the syllabus.” It’s precisely the twentieth century, the period that has left us the heaviest legacies, with all their ideological burdens, that seems to be the least studied in this country. Do you think that the most recent generations of artists are working on the theme of memory in part to draw attention to certain blanks and to try to fill them in?

In reality, I too never got to many of the events and facts on which I’m focusing now with the program of study at school. My method of inquiry and research is very fragmentary, a metaphor for our attempt to reconstruct history through personal stories. I have always been struck by the almost total impossibility of finding an effective and original way of reconstructing history, avoiding second-rate pedagogy. A method based on historical research capable of including the individual part, while avoiding at the same time the rhetoric of the individual. Certain documentaries remind me of interviews of witnesses when something happens. How many kilometers were you from the incident? Did you know the victim? Witnesses who were present at the event and will never grasp the more reflective aspect of their memory.

With The Undercover Man, whose protagonist is the famous Joseph Pistone/Donnie Brasco, you have analyzed all this.

For me, The Undercover Man is a reflection on the documentary, on the possibility of presenting and recounting a constructed story as if it were a “true” story. There is always an editing, a choice, a reconstruction: even in the documentary. Let’s take The Sun Shines in Kiev (2006), a project that includes a film, three slideshows and a poster linked to the ways in which the accident at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant was reported and to the story of Vladimir Nikitovich Shevchenko, one of the first film directors to arrive on the scene. In the film you can hear two discordant versions one after the other, even though they are told by someone very close to the subject and the event, like Shevchenko’s wife. It’s not just public institutions, but individuals too who create situations in which it is hard to establish what is the true version of the facts. For my part, in works like The Undercover Man and The Sun Shines in Kiev, there is not even an attempt to create a coherent story through a multitude of accounts, traces and images. The Undercover Man puts all the material on display as if it were a collection of samples: there is the narrative method, represented by the device of the voiceover; the presumed objectivity of the interview, for which we constructed the set; the moment of the take; the omnipresent editing, given that over and under the image run the numbers created by the photo-and-film camera. The Undercover Man leads to a discovery of the mechanism of cinema and the documentary, starting out from the reconstruction of this real figure, who is an undercover agent and therefore a person who in his everyday life is lying continually so as to be able to carry on his investigative work.

Is analyzing fiction and its mechanisms a way for you to carry out a critique of current events, of the building of political consensus?

Perhaps. I think that coming up today with a different system for telling stories that everyone knows is the most effective way of making sure they reach their destination. There’s nothing new about Naples and the Camorra, but it’s the way that Saviano wrote Gomorra that turned it into a bestseller worldwide. The example I like best is that of the graphic novels of Marjane Satrapi, which she uses to tell hard-hitting stories about Iran, but with an immediate, ironic and poetic tone. Perhaps traditional journalism is a bit worn out. It’s nice to think that there are other forms capable of telling you about a situation without shoving it in your face.

Rossella Biscotti, The Undercover Man, 2008. Courtesy: Prometeogallery, Milan/Lucca.

In the series of photographs Everything is somehow related to everything else, yet the whole is terrifyingly unstable (2008) that you made for the Museion in Bolzano, we see you walking along the top of the wall that used to run around the city’s Nazi concentration camp. I like the way in which you reveal your sense of vertigo, the risk of losing your balance in the face of a story that cannot be told.

That seems a very fair interpretation to me. I feel that vertigo as an individual in response to these episodes which are so intense but so distant, like black holes about which much has not been said, with silence being preferred in part for painfully personal reasons. And then I feel it in general with regard to history. With my agoraphobia, I wanted to put myself completely on the line with respect to that place, whose boundary wall is almost intact, incorporated into a contemporary urban situation: a former working-class district of public housing units. Many of the residents are fairly well aware of what it represents. There’s a recent plaque, and every year there are people who come to visit it, with emotion, sadness and a desire for commemoration – although the numbers are growing ever smaller, owing to their age. In daily existence, the place has a very simple life: one part is used as a parking lot, on one side there are apartment blocks, on the other a portion is covered with plants; one part is in ruins, one restored. When the Museion invited me to do a site-specific project, I didn’t want to work on that theme, even though I was familiar with it. Then one day when I was walking around, I found it in front of me, without any way out. I thought it surrounded a military zone, then I realized that it was a vestige of the concentration camp. And the wall won.

A book that I liked very much, in high school, was The Historian’s Craft by Marc Bloch, one of the founders of the French Annales School. It’s an unfinished work, as Bloch was shot by the Gestapo as a member of the Resistance in 1944. It opened with a question: “Tell me, Daddy. What is the use of history?” And argued that it was necessary to study “the past in relation to the present and the present in relation to the past.”

Yes, I agree totally. For me there is no break between past and present. I pass easily from one situation to the other, in an “ahistoricized” manner. I feel involved in historical events, just as I do in contemporary ones. Both are of use to me. Seeing that I have a very practical, empirical approach, I usually have no problem in finding somebody who knows, speaks, remembers. Sometimes I wish I could do it with many historical figures too.

And the history of art, what use has it been to you?

Here too, I never got to the end of the study program. I stopped at Warhol, making a few leaps along the way as well. I discovered it a bit at a time, through the works, the philosophy, the biographies, some catalogues. At the academy in Naples the frame of reference was more local, focusing on situations better known to the teachers, like Marina Abramović’s performance at the Fondazione Morra or Lucio Amelio’s Terrae Motus project. Which was positive too, as it’s good to study something and to be able to go and see it immediately.

In recent years, in addition to the history of artists there has been much study of that of exhibitions too.

I think that there is a return to a wider documentation, which includes not just the work but its context, the architecture, the display: the exhibition as a project, in short. As far as my work is concerned, it’s what I’m trying to do too. It took me a while to realize that it’s a necessary step. I’ve just come across a very beautiful catalogue that illustrates all the exhibitions held in the sixties and seventies by White Wide Space, a gallery in Antwerp. Apart from a parade of all the conceptual art of the period, what you notice are the discordant elements, like windows and radiators, the way in which the work is inserted in the space, negotiating its own location.

Your “anti-monument” for the Carrara Biennale, Gli anarchici non archiviano (“Anarchists Do Not Archive,” 2010, ed), which won you the Premio Michelangelo 2010, is located in a very evocative space, an old laboratory, with its feet literally planted in the past. And it’s a monument in reverse in part because, formed out of printing-press letters laid out on large iron tables, it only becomes legible when you invert each line in your mind.

It’s a work dedicated to the anarchists of Carrara, who have left a crucial mark on the history of the city. Here anarchism has had a strong syndicalist, collectivist tradition, linked to mutual aid and the territory. When the quarrymen went on strike, the stevedores worked and paid the cost of sustenance for the others, opening up their kitchens to all. There are five sculptures: two larger ones start out from the International, with materials drawn from the resolutions of its congresses. They are fragments of texts, documents, reports and letters that come from three files on three different people: Alberto Meschi, Ugo Fedeli and Hugo Rolland. Meschi, founder of the newspaper Il Cavatore (“The Quarry Man”, ed), is a real legend in Carrara, commemorated by a monument in the city’s main square. Fedeli was secretary of the Federazione Comunista Libertaria and the Federazione Anarchica. Rolland, an Italian who emigrated to America and then to Paris, was a correspondent of Meschi’s and the author of his biography. The small tables are more specific, with subjects like the Carrara uprisings of 1894, illustrated by police records of people arrested, wounded and killed. When you read them you find surnames, first names, jobs: there is even part of the interrogation of an anarchist sculptor. Another table is devoted to an international congress held in 1968. I tried to do research in the Germinal archives in Carrara, but it has been closed down by the police, transferred and is not yet available. So it was suggested that I look in the International Archive for Social History in… Amsterdam! There I found almost everything.

Rossella Biscotti in collaboration with Kevin van Braak, Il ripristino della vasca vuota, video, 2006. Courtesy: Prometeogallery, Milan/Lucca.

A demanding piece of research. And yet you decided to make the results difficult for the public to take in.

I was interested in the idea that this work was fraught with potential, that it invited people to get involved. A not entirely didactic relationship, based on interpretation, that required an individual effort.

Do you intend to print those texts anyway?

Certainly, but I still don’t know in what setting. On the one hand there is the context of the city for which the works were created, with which they remain connected, on the other that of art.

It’s also one of your first true sculptures. Are you moving toward different media?

It’s the second sculpture I’ve made. The first was Presente! (“Present!”, ed), a device that every thirty seconds projected for a fraction of a second the word that serves as its title. Gli anarchici non archiviano functions as an invitation to read, to reconstruct stories. In a certain sense, sculpture is a liberation, from technology as well. In the video there is always an aspect of intricacy that I’ve never found entirely convincing. And 16 mm has become a fetish. Presente! is a machine that fires a word as quick as a flash, but the end result, what you see, is almost nothing but the machine. In its own way, the sculpture for Carrara is also a machine of reproduction, a reflection on communication, propaganda and the distribution of ideas. And thus on my work.

Rossella Biscotti, The Undercover Man, 2008. Courtesy: Prometeogallery, Milan/Lucca.

Rossella Biscotti, The Undercover Man, 2008. Courtesy: Prometeogallery, Milan/Lucca.

Rossella Biscotti, Gli anarchici non archiviano, 2010. Photo: Gennaro Navarra.