8 November 2013

In response to great demand, we have decided to publish on our site the long and extraordinary interviews that appeared in the print magazine from 2009 to 2011. Forty gripping conversations with the protagonists of contemporary art, design and architecture. Once a week, an appointment not to be missed. A real treat. Today it’s Rosa Barba’s turn.

Klat #02, spring 2010.

The work of Rosa Barba, an Italian artist who has lived in Germany for many years, develops in the intersections between different media like film, sound and written text. In her films she constructs narratives that are often wrapped in a sense of mystery, which meets with very personal expression in a series of short films without images, cinema experiments constructed using only texts and subtitles. Rosa Barba’s works, always shot with film, investigate the fine line between documentary and fiction, forming dystopic universes without precise temporal coordinates, in which it is nearly impossible to pinpoint events, as if they were trapped in a time machine.

Let’s start from the beginning. You were born in Sicily but left Italy very early and moved to Germany. Can you tell me a bit more about your family history and your relationship with your Italian roots?

Yes. My parents emigrated to Germany from Sicily. I grew up in an Italian interior and the exterior was culturally German. At home we watched Italian movies and listened to Italian radio stations and at my friends I watched and listened to the German channels. Italian culture was always very familiar and natural, the “outside” world I loved to observe and I knew how to function in it.

What do you remember of Sicily?

Processions in the streets, wedding parties, sitting hours with old aunts and great-grandmothers on balconies and listening to their stories. I still go there regularly, nothing really changed.

What is your strongest memory of your Italian childhood?

Slowly approaching the island by sea, on a ferry, and finding myself in front of a Madonna with open arms, at the entrance to the port. She was physically every year in a worse condition and made a great impression on me.

Rosa Barba, The Empirical Effect, 16mm transferred to HD, 2010. Courtesy: Rosa Barba, Galleria Giò Marconi, Milano and carlier | gebauer, Berlin.

Do you still feel very connected to the Italian culture?

Yes. But I feel mostly connected to the landscape.

Do you consider yourself an Italian artist or more like a German artist?

I’m not sure about this definition. I would define myself as an independent artist. I grew up in Germany and went to school there. But my parents have always kept an Italian lifestyle. I feel Italian when I am in Germany and German when I am in Italy. My friends come from different parts of the world and I communicate mostly in English with them.

You shot a few works in Italy. Do you want to talk about your fascination for the Italian country, maybe in relation with The Empirical Effect, the film you recently did in Naples?

I shot many of my longer films in Italy. Maybe because I can be a familiar observer with a certain distance, since I don’t live there. The society portrayed in The Empirical Effect lives at a high level of tension, yet paralyzed and somnambulistic. Along the hillsides of the sleeping monster Vesuvio, the mafia finds their hiding place and an uncountable number of illegal Chinese workers builds up a secret parallel society. The main attention though is aiming at the Vesuvio where nature is exploited like a big media spectacle. Cameras track the volcano’s actions, seismographs detect every slight trembling of the earth. Tourists love the sight of the mighty mountain. As soon as politics need distraction the news announces an unusual activity at the Vesuvio. Even history is ironical there: the last outbreak was parallel to the bombing of the Second World War. Some of my protagonists in The Empirical Effect were witnesses of this catastrophic outbreak of 1944. I invited them to move with me into the old observatory next to the crater. The Vesuvio volcano is a metaphor for the complex relationships between society and politics in Italy. It’s unpredictable, powerful, sexy, destructive and based in the middle of the most densely populated area alongside the Mediterranean cost. No one is able to control this immense force of nature and yet it connects the inhabitants and their environment with an invisible tie. Any attempt to tame the volcano seems vain. Yet it creates a high level of awareness for even the most marginal aspects of live. And there is magic working, too: esoteric rituals, arcane machines and cabalistic drawings which are supposed to hold back the volcano’s temper. In this project I weaved a fiction around the Vesuvio which I shot during an evacuation test in summer 2009. For the first time ever, some early film documents of Naples by the Lumiere brothers are seen as part of the film. I worked closely with the Osservatorio Vesuviano in Naples and some inhabitants of the “red zone”.

In 2008 you were invited by Francesco Bonami on a large-scale survey of Italian art called Italics. Italian Art between Tradition and Revolution, 1968-2008 at Palazzo Grassi in Venice and MCA Chicago. What do you think about Italian art nowadays?

I think I know more about Italian movies than artworks. But I adore some artists from the Arte Povera movement, like Giovanni Anselmo. My favorite piece at the Italics exhibition was by an old Italian artist called Salvatore Emblema.

You have recently moved from Cologne to Berlin. How do you like it there?

I studied in Cologne and shortly afterward I started to work a lot abroad with residencies or projects. I went for a few years to Amsterdam as well when I got invited to the Rijksakademie. I never really gave up a little base in Cologne since recently when I decided to have my base in Berlin. I like it a lot here. Finding a studio was easy, and many people I have been meeting and also working with abroad within the last years seem to come at some point to this city.

Rosa Barba, Western Round Table, 2007. Courtesy: Rosa Barba, Galleria Giò Marconi, Milano and carlier | gebauer, Berlin.

You mention the realm of cinema. Can you tell me what you like in that, what kind of movies do you watch? Do you go often to the movie theater? How many movies do you watch per week? Do you also watch TV?

There were times when I watched movies every day and often went to the cinema. At the moment, I read more about cinema. I almost never watch TV.

Have you always been interested in film or, in the beginning of your career, have you tried different mediums?

Photography first, then film. And always, music and sound.

Is there the work of some filmmaker that you admire specifically?

Early films of James Benning, Robert Frank and Jonas Mekas, but also Pasolini.

What brought you to be involved with the arts?

I’ve been working with photography since a very early age, when I inherited a camera. Very soon I continued with moving images and integrating them in a space. Working during my studies as a projectionist, must have shaped my interest in integrating the machineries together with the images in the space.

Did you study art in school? Where?

Academy of Media Arts in Cologne.

What was the first artwork you ever made?

House sitting different people’s homes and living their lives while they were away. Most significant was the life of painter and animation filmmaker Hal Clay in Munich. I started to work on his 16mm Steenbeck. Parallel to this, I made my first photo-book.

Can you tell me about your choice of using film as opposed to video. What brought you to film? What are the aspects that you most like in such a medium? How is the medium itself present in your work?

I started to work with photography at a very early age, then moved to super 8. At the Academy in Cologne, I started working with 16mm, which I felt naturally familiar with. During a residency in Budapest, I obtained the exact same familiarity with a camera I had used at the media academy from a Hungarian filmmaker, who had been a member of the Béla Balázs studios. Since then, I shoot my films with this camera. Trials with video never gave me the same satisfaction. In some of my works, I use the film material as well as a physical element in space producing “drawings” in the space, conceptually connected with the projected image. In recent film-sculptures, like Stating the Real Sublime or Enigmatic Whistler, both of 2009, the material takes over and leads the machine. A kind of anarchic gesture. In the first one, the projector is suspended from the ceiling by its own celluloid material, which is playing back sound from the optical sound track. The material and the “soundstory” are trying to physically balance the white projection screen.

So, in some way, the film is not only support that allows the moving image to appear, but it become also a sculptural element in your work. In other works like Machine Vision Seekers, 2003, the projector also becomes protagonist of the piece, for it moves on itself projecting the image on different sides of the gallery. Can you tell me about the idea behind it? Is there a particular fascination for the object itself or is it more for the final visual effect of the projection moving through the space? Can you also talk in this context about Western Round Table?

In general, I prefer not to hide the source of the projection. Some works are meant to work as “sculptures”, such as Western Round Table, 2007. The presence of the projector often adds the presence of a narrator, and emphasizes the question of whether it is an archival work or a fictive one. Western Round Table is my interpretation of a meeting on Modern Art held in 1949 in the Mojave Desert. A group of men – from the disciplines of art, literature, criticism, music, science, philosophy and architecture, and which included Marcel Duchamp, Frank Lloyd Wright and Gregory Bateson – discussed contemporary artistic practice, its modernist legacy and its modernist future. The exact location of their meeting is unknown. I wanted to build an enigmatic monument to this meeting, making this source material into something abstract, outside of space and time. The two projectors are facing each other and they “speak” at the same time, projecting loops of clear 16mm film with each carrying an optical soundtrack of faint chimes (one bass, one melody). The light of each projector’s bulb throws the enlarged silhouette of the other onto the gallery walls, their shadows looming like characters. In Machine Vision Seekers, the viewer becomes a protagonist in the piece. A story of an emigration which takes place in complete darkness, a group of people grope along a dark corridor below the earth to find their point of departure. The text presented in the work plays with the visualization of notions and thoughts in an invisible environment, leaving the two dimensional screen. I constructed a mechanically moving film projector to throw the words, which create the story, with unforeseen movements against the wall. The film is edited “live” in the space and by the viewer. The viewer can find in the neutral gaps its place for observation.

Rosa Barba, Stating the Real Sublime, 2009. Courtesy: Rosa Barba, Galleria Giò Marconi, Milano and carlier | gebauer, Berlin.

Can you tell me about the trilogy Western Round Table, They Shine and Waiting Grounds, 2007, and your interest for the Mojave Desert in California?

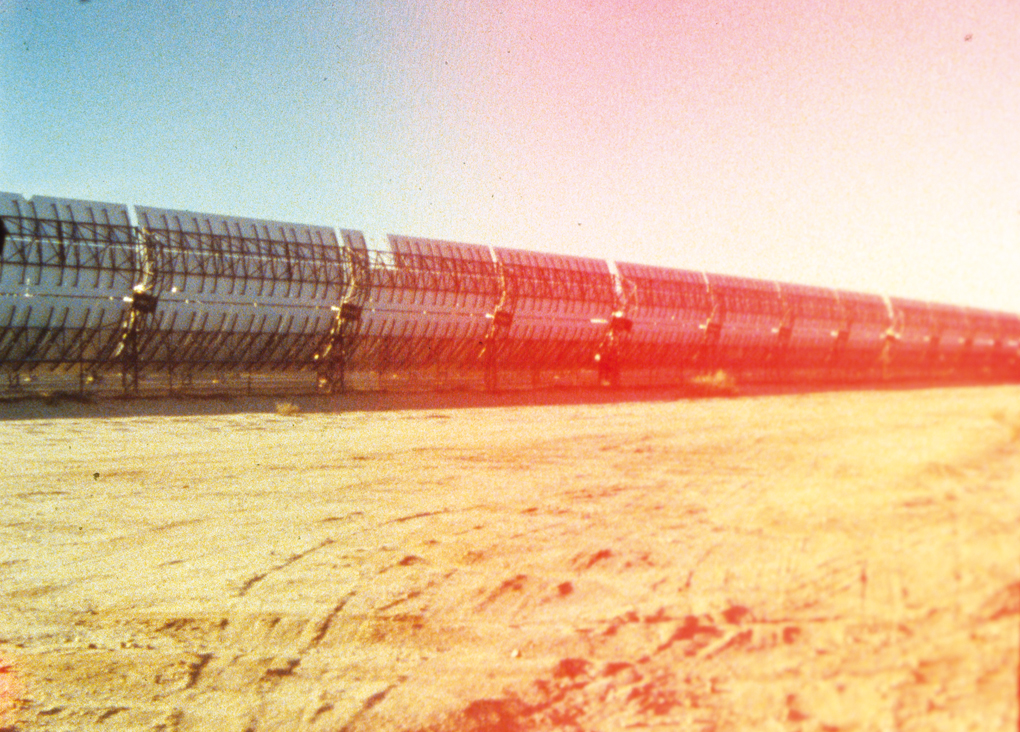

In all of those works, I see the landscapes as “documents” where I place my stories. Around the time of the Second World War, this vast area in the Mojave Desert became a testing site, primarily for military purposes. As a consequence, the landscape is littered with evidence of both our future – vast solar energy and windmill parks –, and our past – trailer parks, heaps of scrap metal and the largest airplanes graveyard in the world. Waiting Grounds documents the voyage of a group of people through a series of abandoned locations. Their dialogue, and their questions regarding the function of the architectural remains, alternate with images of those locations, which are never shown in full light and never clearly visible. I worked with the landscape, which already represents history, as a setting to which I add my fiction. The fictional layers can have different dimensions. In They Shine, there is another sound layer of “document” on top of the visual layer, which shows the sculpture formed by the solar panels in the desert. The fictive sound layer is inspired by interviews with people living in the desert, imagining the possible future architectures there. The future is as important as the past and the present. New ideas can relate to historical moments and offer you a layer of new possibilities.

I’ve always liked the combination of visual and sound in your films. It seems as though you were trying to tell two different stories, either merging images and audio or completely juxtaposing them. What comes first, the image or the narrative? Do you write your own script or do you appropriate already existing narratives?

I find my stories writing them, as I find out information about certain places, people, societies, etc. Stories for me are not necessarily the content of my pieces, but rather the carrier to lay out the different aspects of existence. Each object, place, machine and human being is part of a set up, which I try to portrait and see from certain perspectives. I always try to give as much space as possible without losing the story. There are also breaks and jump cuts as linearity is not always helpful to find the connecting pattern of all these elements. I’m still a film lover, but the cinema architecture in which you sit and see the movie and the projector machines, the smell and the light intensity of the projection, all play an important part in how you perceive the story. When I was working as a projectionist in a cinema in Cologne, still a student, I once mixed up the three reels of a movie. I showed the end of the movie in the middle and the middle part in the end. No one noticed.

I guess this gave me a whole new idea of what cinema

can do.

Can you talk about the music in your work? How do you select it? Have you ever composed it?

I usually work with one or a small group of composers who are very close to my work and intuitively understand what the stories are about. I try to involve them as early as possible in a project. I usually also include field recordings which often record myself. Some cores I play myself. Jan St. Werner, who is my main partner in sound, is a musician, but also patient music listener. He tries to hear what the film is carrying, emphasizing certain aspects of the story. I’m also not afraid of explicit musical moments, so I’m happy to let the musicians work on their musical scores, as much as I try to keep the overall atmosphere unmusical and open. The collaboration with Jan St. Werner, sometimes together with Andi Thoma, has been lasting for about 13 years now and I know that he understands my works in a way which does not need much explanation.

How do you choose the subjects of your films?

I find them spending time on location and speaking to people. Mostly elderly people who live at the place since a long time. I try to find out about things which are about to be forgotten and reconstruct them from my point of view with as much info from natives as possible.

Rosa Barba, Coro Spezzato: The Future lasts one day, 2009. Courtesy: Rosa Barba, Galleria Giò Marconi, Milano and carlier | gebauer, Berlin.

Your film work alternates between very visual films, hovering between documentary and fiction, and work that are purely text-based. Can you talk about these two typologies?

There is a thin line between fiction and reality and basically both terms are often based on hierarchies and stereotypes which are dominated by power structures, like governments and media. When I try to find a topic for a work, I look for information which isn’t clearly documented and relate to spoken translations, stories, opinions and documents which are not in the public eye. This way, I find stories off the main road which reveal a lot about a certain society or landscape. In some works, I leave out the images as visual information in order to minimize and concentrate the message. This works tend to be more conceptual.

Let’s talk about the work Coro Spezzato: The Future lasts one day, which you showed at the 53rd Venice Biennial. How did you decide to present that particular work? Can you take us through the genesis of the work, from day 1 until completion?

The installation consists of five 16mm projectors that form a chorus. The idea behind the installation is the Venetian polychoral style of the late Renaissance and early Baroque times, a type of music which involved spatially separate choirs singing in alternation. The theocentric construction of the world was slowly replaced by a humanistic idea of reality, and choirs were allowed to sing about ideas as well. The lyrics projected as text fragments make a statement for the future, and analyze the status quo with a multitude of voices. The projectors are coordinated with each other and speed up or slow down according to the text. They are following a choreographed order by capturing a moment of reformation and translating it into a silent choreography. I had this work in mind for a long time, but couldn’t figure out the best way how to synchronize projectors in this particular way, so they create a “humming” via slowing down and speeding up. When I got invited to the Venice Biennial by Daniel Birnbaum, I thought it would be the perfect place for it, since this is the place where the idea came from. I managed to realize it with the help of a programmer, my film-technician and a very mathematical editing process of mine, which took me about 7 months of concentrated realization.

How was your experience at the Venice Biennial, probably the most important art event in the world?

Of course, it was a great honor to participate in this group show. I was mainly busy with this complex new piece and spent all my time in my exhibition space during installation time, but enjoyed the event and the city after the opening very much.

The first time I saw your work was in 2005, in Berlin, at Croy Nielsen, at that time a small exhibition space located in a remote apartment in East Berlin. In that exhibition, you collaborated with David Maljkovic. Can you tell me about that show and about the experience of collaborating?

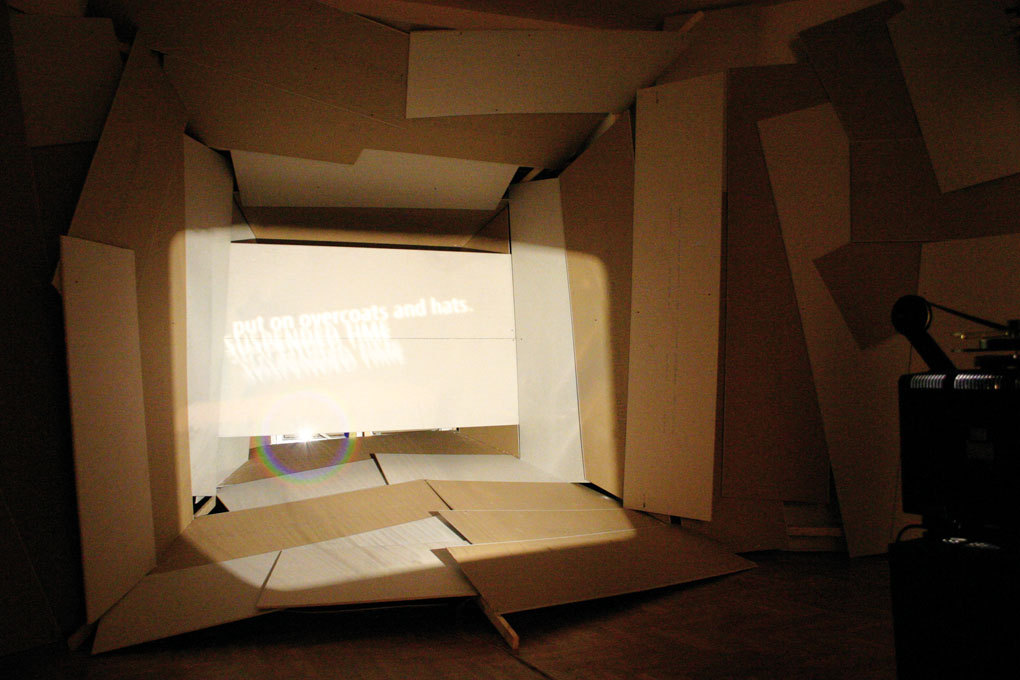

David built a cinematic sculpture in which I projected my 16mm film, It’s gonna happen, a conspiracy phone call conversation on the optical sound track and a parallel investigation of the surrounding on the image layer. The exhibition was a very nice experience, since we installed in a very familiar atmosphere in Croy Nielsen’s apartment. It was very surprising when suddenly the opening arrived and we had about 400 people in there.

You have also more recently collaborated again with David for the project Handed Over, in Dublin (2008). Tell me about that exchange.

David and I met at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam where we kept exchanging ideas. For an exhibition I organized in my studio in Amsterdam, called Telegram, I invited a few artists with whom I was exchanging a lot the last years. It was a nice event that went for 3 days and nights. There we decided to attach one of my films to a structure David built. Henrik Nielsen saw our collaborative work there and invited us to Berlin. At the Project Art Center we were asked to create a collaborative piece from scratch. So we started a written conversation via e-mail, a kind of chain-fiction. In the meantime, we shipped a super 8 camera back and forth from Zagreb to Stockholm, where we were living in that moment. We didn’t know what the other had shot when the camera arrived. The images grew independently from both sides.

Are you planning other collaborations?

We haven’t planned another project yet, but it is possible.

Outwardly from Earth’s Center is a very good example of the way you merge facts and fictions. Tell me about the experience behind this film.

Facts and fiction are often hard to distinguish. In the case of Outwardly from Earth’s Center, we are confronted with factual or near-factual situations where a population faces imminent danger of some sort, due to the fact that the surface that they inhabit is in movement. My films take place in locations that can be used as metaphors for “realized utopias”. Here the Island becomes a metaphor for an idea. The places, as well as their narration, have their own principles within different layers. It’s like listening to a voice from a tiny part of a society which is constantly re-forming itself by also asking the viewer to continually take a new position. The drift is the possibility.

How long does it usually take you to edit a film?

Editing is a very concentrated period of 1 or 2 months. I tend to go back and re-edit the films after I screen them for the first time.

Rosa Barba and David Maljkovic, It’s gonna happen, 2006. Croy Nielsen, Berlin. Courtesy: Rosa Barba and David Maljkovic

In 2008 you did a web project for Dia called Vertiginous Mapping. How did you like that?

Usually, I use metaphors in my films that relate to a political aspect. In my web project commissioned by Dia, I produced for the first time a film for the web, which I enjoyed very much. I saw it as a special way of editing and reading the source material. Alkuna’s crack in Vertiginous Mapping – a literal, physical threat – serves as a metaphor for unchecked corporate power, which is destroying natural resources and shifting people’s homes as if the company owned them. In my work I don’t observe reality. I am reinterpreting it in a certain direction by making very personal decisions. I don’t pose critical questions, I am trying to invent a utopia. I try to show political and social mechanisms set against technical mechanisms which themselves are fragile. The paradox which results from such a tension is used to posit a utopian solution to the problem, a kind of magic which stops time and offers a slowed-down view of otherwise hidden aspects of reality.

Can you tell me something about your ongoing work at the Centre international d’art & du paysage of Vassivière?

It’s a Land Art piece that works in an artificial way, but refers to the fascinating, mysterious, natural landscape surrounding the art center of Vassivière. It is a sculptural piece in which I simply bring out aspects of the location that would otherwise remain hidden or get overlooked. I have created a set-up of machines that transform the art center into a giant projector, to project the surrounding landscape.

And what about Shanghai-container?

I’ve been invited from Skor in Amsterdam to propose a public space work for the new harbour in Rotterdam. From this spring, a container which I transformed into a cinema will leave towards Shanghai and ship my film A message to Shanghai to China. The film will be produced in Rotterdam with the help of mixed population living around the harbor.

Since 2004, you have produced a wonderful serial publication called Printed Cinema. Can you give us a bit of background of it? Do you see it as a separate project or more like a completion of the film works in another medium?

The publication project Printed Cinema (2004-2008) – ten irregular periodical issues – continued, in parallel to my audiovisual work, as a personal reflection on the essence of cinematography. Gaps, ellipses, dialectics between images are essential in that respect. In Printed Cinema, I tried to translate my movies into a printed matter. This is expressed in the editing principle, as well as the oppositions between film and printing, between text and image. In this way, Printed Cinema should challenge the outer edges of an artist book. Each issue refers to a project of mine and functions like secondary literature to a former project, but can stand also on its own. I wanted the magazines to start an own life through their distribution. Each magazine appeared in one location in connection to an exhibition of mine and was available for free for a certain time period, in a limited amount. I saw the distribution as a way to set up “screenings” in different places, where I have been with my work. The “screening” continues for free until the magazines disappear.

Rosa Barba, Photo machine, 2006

Rosa Barba, They Shine, 35mm, 2007. Courtesy: Rosa Barba, Galleria Giò Marconi, Milano and carlier | gebauer, Berlin

Rosa Barba, Waiting Grounds, 16mm, 2007. Courtesy: Rosa Barba, Galleria Giò Marconi, Milano and carlier | gebauer, Berlin.

Rosa Barba, Outwardly from Earth’s Center, 16mm transfered to video, 2007.