22 May 2013

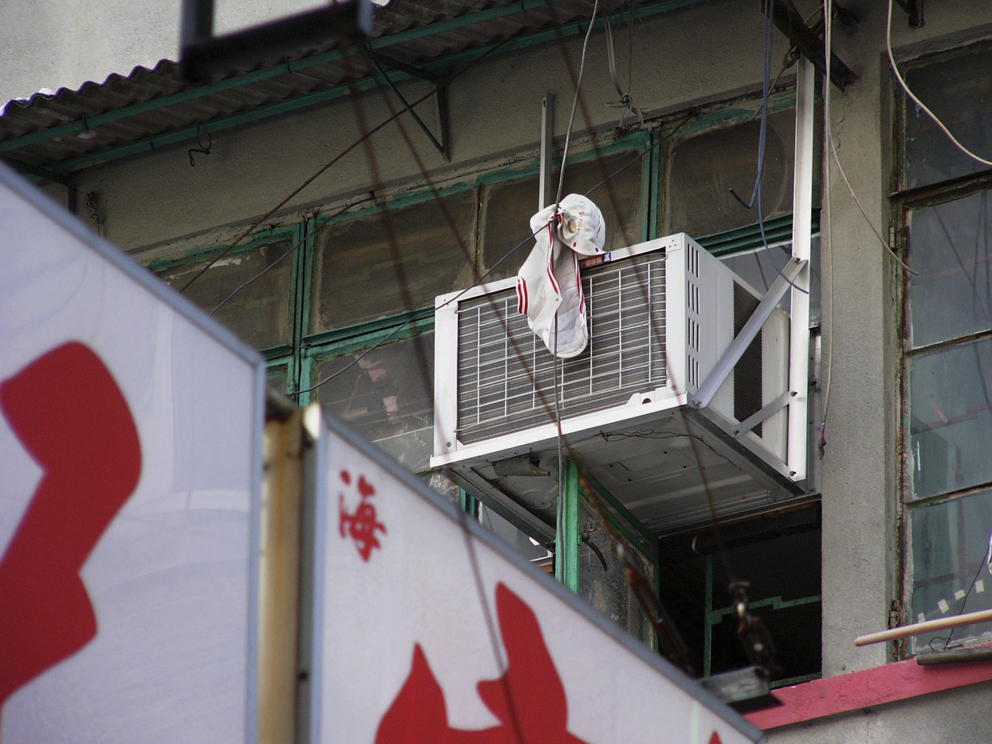

No one saw it. Amidst the tall skyscrapers of Hong Kong, architectural rules over fifty stories high filled with tiny apartments, no one had noticed it. That still damp pair of underpants had fallen from the skimpy windowsill of some 18th story or other. Nobody, in the whole city, was aware of that lost washing. Except one: Michael Wolf. The German photographer, who has been living in Hong Kong since 1994, explains his brainwave while seated, a foreigner surrounded by Chinese, in one of those diminutive restaurants in the vicinity of Sheung Wan. He explains the idea that lies at the root of all his projects, from the pictures of Lost Laundry, shown at the last Shenzhen & Hong Kong Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism and Architecture, to those of Earth God shrines, just published by Peperoni Books under the title Small God Big City and protagonists of an exhibition at the Galerie Wouter van Leeuwen in Amsterdam.

Shall we start out with a detail too? You are left-handed, and like all self-respecting left-handers you use the right hemisphere of the brain, associated with creativity, intuition and the perceptual and spatial functions of the imagination, which for a photographer is not an inconsequential detail. How is that, at a certain point, an idea comes to you?

While everybody is looking in one direction, I notice the detail, the one thing that nobody else has noticed. I see one, then another and another until those pictures turn into a series and then the series becomes a project. It’s not that I have a single grand scheme at the outset. My mind follows my gut instinct. It’s an unconscious thing, there’s nothing premeditated about it.

Born in Munich in 1954, you grew up in Europe, Canada and the United States. You studied under the great photographer Otto Steinert at the Folkwang Academy in Essen—from which Pina Bausch graduated too—and at Berkeley in California. As a press photographer, you won the World Press Photo Award twice, in 2005 and 2011, and for eight years you contributed to the German weekly Stern. Since 2001 you have chosen to devote yourself to your artistic projects. What did you dream of becoming as a child?

I didn’t have one particular dream when I was a child. The only thing I was interested in was the flea market. I was capable of spending hours there, with my mother, while my father fumed in the car. I used to collect stones; today, in a certain sense, I collect photos. Let’s say that I’m a compulsive collector who is afraid of getting bored. The series called Bastard Chairs, devoted to original seats I came across all over China, was nothing but a collection: I photographed one, then two, then a hundred of them. But the detail has a profound symbolism, because sitting in the Middle Kingdom is not the same as in the rest of the world, it has a metaphorical significance. Here their chairs have just one purpose: functionality. I always say: it is designing, but without design. That’s not all. After taking pictures of them, I take them home and keep them all. I hoard objects because they are able to tell stories.

Street View, Fuck You #10, 2010. Photo: © Michael Wolf.

You have taken pictures in every corner of the globe, and in the end you chose Hong Kong: the fragrant harbor, capital of Asian finance, a metropolis with over seven million inhabitants.

I didn’t know exactly where I would end up. In 1993, I left Germany with my wife, but didn’t find anywhere that really convinced me. When I arrived in Hong Kong in 1994, every inch of my body said yes. For two basic reasons: the cuisine and the closeness to China. In 1995 China fascinated me. It was a mysterious and mystical lair, with its difficulties and an enormous cultural difference from Europe: there a Westerner always remains a foreigner. In Hong Kong it’s different though, because there are many immigrants and there is never any privacy. Hong Kong is a city filled with paradoxes. You never get bored, as you might in Paris for instance.

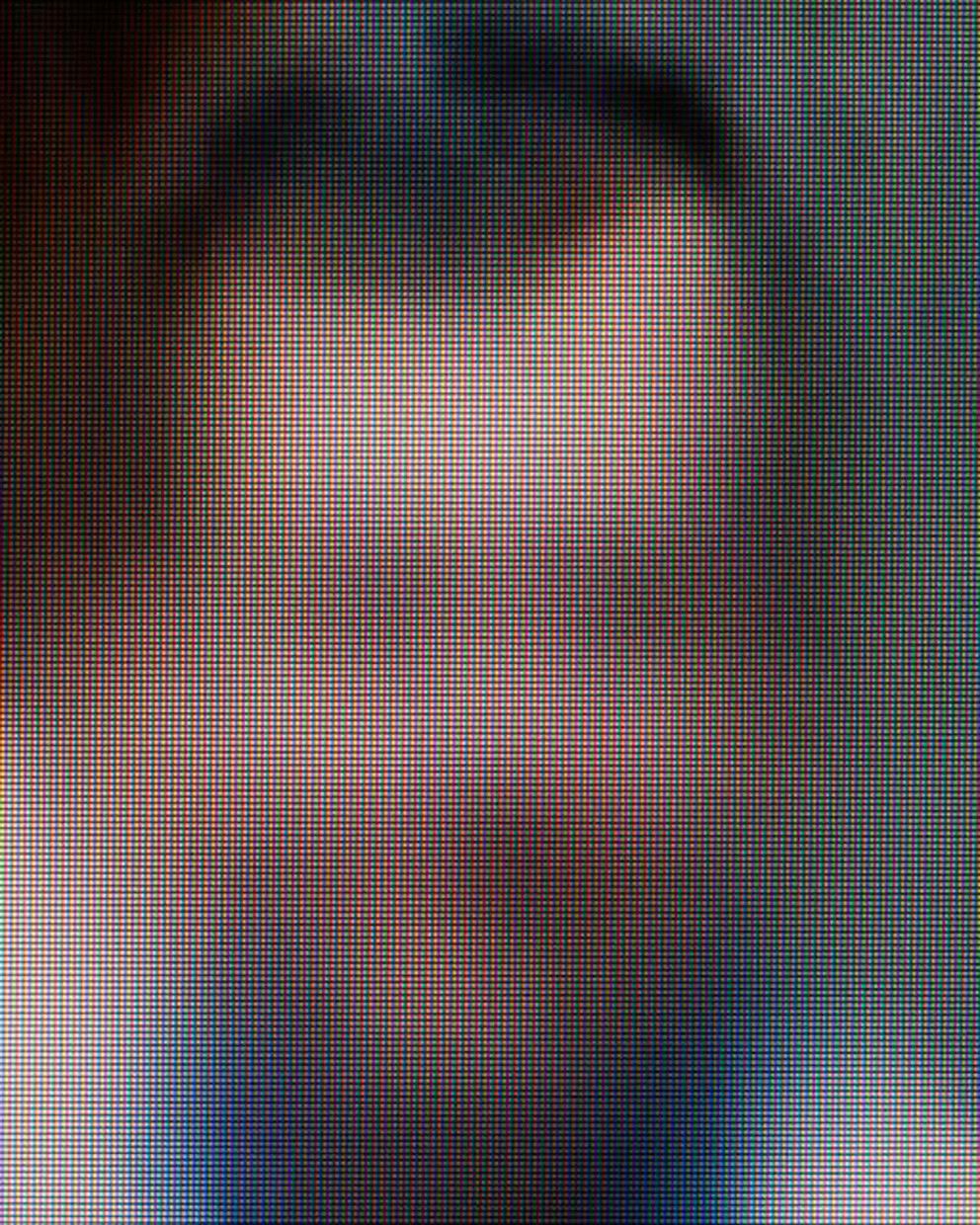

Speaking of Paris, in 2011 there was a lot of talk about the use you made of Google Street View to carry out a project that earned you an honorable mention in the World Press Photo competition. What was it like sitting in front of a computer from the beginning to the end to develop that project?

I sat there for hours and hours clicking through the street views of Paris. It took me six months and out of it came A Series of Unfortunate Events, Fuck You and Portraits. It was a conceptual and experimental work. What Google does with people’s lives is incredible. I couldn’t believe how a telecamera could be there at certain moments: from the heart attack in the middle of a road to the woman squatting to pee in the open air.

From photojournalism to art photography. How much courage did it take to make a choice of that kind?

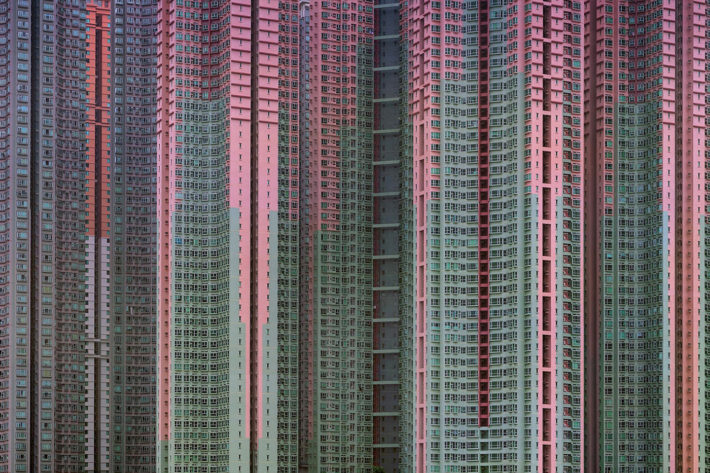

I was lucky, happy people are always lucky. The beauty of being an artist is that you’re totally free, with art you can do anything. My main focus has always been on the megalopolis. One of my earliest works was Architecture of Density, on the buildings of Hong Kong. Everything depends on the human aspect. Even works of architecture, with their fascinating structures, have a strong human component. If you look at them from a distance these photographs seem abstract, but then you come closer and notice pants, underwear, T-shirts: you realize that behind every window is hidden a person.

There is a symbiosis between public and private, and in a city like Hong Kong it’s even more evident.

There is a very close connection between public and private. In Lost Laundry, for example, the private becomes an integral part of the urban landscape, it can tell you something about the city itself. In Hong Kong it is forbidden to hang out your washing, because the government thinks it is shameful to show to outsiders the most intimate things you possess: your bra, your slip, your dirty linen in short. While in the US or Europe people hang out their washing on terraces and in courtyards, here you have nothing.

Tokyo Compression, 2010. Photo: © Michael Wolf.

Among your various projects, different pieces of a single jigsaw puzzle, there is a unique collective sense. Which is the project closest to your heart?

100 x 100. This too is a series immortalizing the interiors of small apartments (100 square feet is roughly equivalent to 30 square meters), in which up to ten people live. Rather than a shoot, it was a ritual: I knocked, asked permission and took the picture. I asked everyone the same four questions about their age, job, home and family. In this case the photography revealed the idea of community, of survival, but at the same time of dignity. Everyone had a chair, a calendar, a clock, a rice cooker: each object tells you something, it depends on the way you look at it: from the viewpoint of sociology, architecture or design.

Your Small God Big City has just been brought out by Peperoni Books.

Small God Big City is a photo book that continues the celebration of the vernacular culture of Hong Kong. The pictures are of the small shrines of the hybrid and secondary deities called Earth Gods, structures housing a legacy of the past, but in a big and bustling city.

Another metropolis, instead, for one your most famous works: Tokyo Compression. The density here is that of humanity, trapped in the Tokyo rush hour, in which you get a sense of chaotic immobility and suffering. This could be one of the ten places not to be missed in Tokyo, that should be included in every tourist guidebook: which stop on the subway is it?

I’ll never tell. It’s one of those little secrets that ought never to be revealed. Other secrets of photography? Keep going back to places: again, again and again. Photography when all is said and done is the only means we have for recording things, for fixing a precise and concrete point, without that margin for the imagination which sculpture and painting leaves you. In ten years, we’ll be able to see what we were like: the past is fundamental because we are the product of the past.

One of your latest projects, Window Watching, has caused a stir. What is it you see through the rear window?

In reality, you don’t see anything particularly exciting, like sexual skirmishes or murders, through the window: in Hong Kong many people are just playing with iPads or reading books. The South China Morning Post harshly criticized me for violating people’s privacy, but I had no binoculars or anything like that, I just photographed what I saw. It’s not my fault that the houses are so close to one another. The architects ought to think about it.

Night #19, 2005. Photo: © Michael Wolf.

Transparent City #62, 2007. Photo: © Michael Wolf.

Transparent City #02, 2007. Photo: © Michael Wolf.

Architecture of Density #108, 2009. Photo: © Michael Wolf.

Architecture of Density #39, 2005. Photo: © Michael Wolf.

From the series 100×100, 2007. Photo: © Michael Wolf.

Street View, A Series of Unfortunate Events #07, 2010. Photo: © Michael Wolf.

Lost Laundry #04, 2012. Photo: © Michael Wolf.

Street View, A Series of Unfortunate Events #23, 2010. Photo: © Michael Wolf.

Paris Rooftops #04, 2014. Photo: © Michael Wolf.

Street View, Portraits #19, 2010. Photo: © Michael Wolf.

Tokyo Compression #05, 2010. Photo: © Michael Wolf.