22 January 2013

In response to great demand, we have decided to publish on our site the long and extraordinary interviews that appeared in the print magazine from 2009 to 2011. Forty gripping conversations with the protagonists of contemporary art, design and architecture. Once a week, an appointment not to be missed. A real treat. Today it’s Nigel Coates’s turn.

Klat #05, spring 2011.

I met Nigel Coates for the first time a couple of years ago, during the preparations for the Venice Architecture Biennial of 2008. Nigel was there to check on his installation at the Rope Walk of the Arsenale. I stopped to ask his views on what, at the time, was the subject of my doctoral thesis. With total calm, without ever taking his eyes off the workmen, Nigel courteously answered all my questions. That was the start of a friendship. We’ve spent time together, usually over something good to eat, talking about architecture, design, art, cinema, cooking, fashion, gossip. Asking Nigel things just comes naturally, to me, so after a day spent at the Royal College of Art I found myself in his London studio to do some “klatting” with one of the most non-conformist designers and theorists of the last twenty-five years. Nigel’s studio is very intimate, warm, populated by just a few trusted collaborators. There are drawings of his projects everywhere. Drawings that look like paintings, and in fact at first glance the office seems like an art gallery in a Victorian building in the center of South Kensington, just a few minutes away from one of the world’s art symbols, the Victoria & Albert Museum.

Good evening, Nigel.

Good evening, Guido.

I wanted to start with a simple, direct question: in what direction is your work moving today?

For a few months now Cristina Grajales Gallery in New York has been showing some of my projects, halfway between art and design. I like to combine industrial design with some objects I can make for collectors. I also arrived at this sort of art design thanks to my experience with Poltronova, which gave me the chance to design special, unconventional objects. I’m interested in experimenting, not so much in making products for an elite. In my career as a designer and architect I have always tried to explore forms that combine popularity and sensuality.

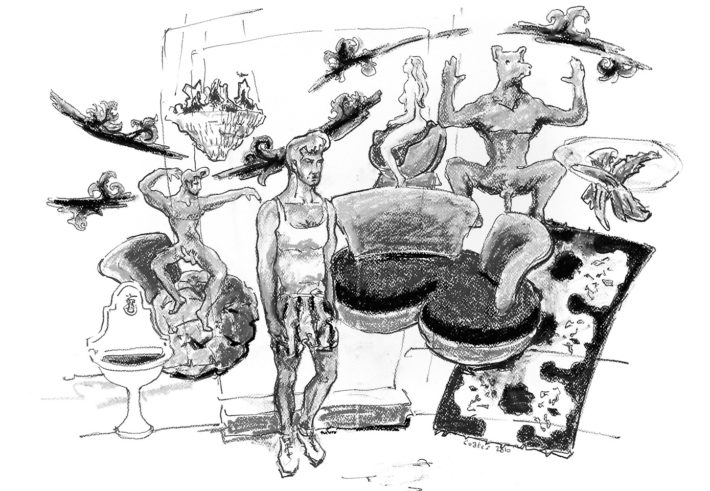

Nigel Coates, Baroccabilly, drawing, 2010. Courtesy: Cristina Grajales Gallery, New York.

Architecture vs. object: on which scale do you think, at first? Do you start with the architectural space or the object?

I start with a context: it might be a city, a street, a room, or all of them combined. Each element is considered in narrative terms, then the story just seems to unfold, gradually revealing a situation, an atmosphere. That atmosphere is what I try to sum up in a design, a work of architecture, an object. I’ll give you an example: in the recent installations I did in London and Milan, there was the desire to show the living space and objects of an imaginary personality of contemporary London: the Baroccabilly. A personality I invented, with its own atmosphere, its own identity.

Has your creative process always run along these lines?

I’d say so. From the start of my career I have always imagined stories and characters to use as references to make spaces and objects. My very first commission as an architect, the Metropole in Tokyo, came from the idea of designing a cafe that would recreate the atmospheres of English gentlemen’s clubs, the romantic, bohemian spirit of the big European spaces of the 1800s. The client didn’t want an academic project, if we can call it that, but the most faithful suggestion possible, through the space and objects, of a European atmosphere that could still not be found, perhaps, in Tokyo. The intention was to manage to communicate the style, the character, the atmosphere of my flat in London, that the client had seen in some photographs. That was the point of reference for the Metropole.

Nigel Coates, Baroccabilly, London, 2010. Photo: Susan Smart.

Why did they see photographs of your home?

Because they were published in Brutus, a Japanese magazine. At the time, my flat had a hybrid style, between punk, postmodern and neoclassical, with the paint stripped off the walls to show the layers below, the personal reworking of classic objects, and a whole series of other things. I wanted to convey the idea of a historical place rediscovered, brought back to light. Everything came from my artistic production, the period I was living, and a certain minimalist attitude of mine. Minimalism, for me, meant scraping, stripping, gradually removing as much material as possible from surfaces, to show the essence of an environment, in contrast with different stimuli and styles. I wanted to make space into a sculpture, a three-dimensional narrative.

This is the idea behind NATO (Narrative Architecture Today) and your concept of narrative design.

Yes. My creative process develops like a screenplay or a storyboard, with one difference: in my case, the sequence of the scenes is not what determines the narration, but a succession of mental images that create relationships between spaces, objects and the people who use them. These images are overlaid by memories, atmospheres and situations, from which the whole project arises. The final product (building, object) is a consequence of all this. If multiple artistic personalities intervene in a project, as happened for the Metropole and for the Caffè Bongo, everything is amplified and the process is enriched by stimuli and suggestions.

What was the goal of Caffè Bongo?

The goal of Caffè Bongo, with its references to the Rome of Fellini’s Dolce Vita, was to express the values of the moment, the eighties, crystallizing them amidst the remains of a culture in movement, contemporary Japan, which was experiencing an architectural and social utopia in which everything seemed possible. With its architecture, Caffè Bongo wanted to encourage the pursuit of latent, unexpressed meanings, that a society in rapid change was leaving in its wake. The venue, according to the client’s wishes, was supposed to attract the attention of the young people of Tokyo; and in fact it was built in a very strategic point in the city, in front of a department store. For this reason, it needed a very strong statement, that was developed above all inside the cafe, and suggested the complexity of European thought according to a Japanese vantage point.

The Metropole and Caffè Bongo, then, came about primarily as projects of architecture and decor. The design of objects came later…

The objects were already there, at the Metropole, but for Caffè Bongo I had to invent them myself. I told my client I could try to imagine all the objects of the venue, and he replied: “We don’t try to imagine the objects, we make them!” This reignited the passion I had had since my childhood: the creation of design objects. As an architect, I have conceived projects on paper, through the classic models and, in recent years, using computerized 3D modeling. When I started teaching at the Architectural Association of London I understood that it might be useful to ask students to design by starting with random objects: objects that were used as “bricks” to construct a model. I remember that in the neighborhood of the Architectural Association there were many electrical supply stores, so the students made models of entire cities using electrical components! Anyway, Caffè Bongo and its objects happened a bit like that, from a very creative experience, from play, full of free associations.

Nigel Coates, Caffè Bongo, Tokyo, drawing, 1986. Courtesy: Nigel Coates Archive.

What design and what architecture stimulate you the most?

The ones that let me glimpse the thinking of the designer behind that object, that space.

Does that happen often?

In the past, the possibility of transferring all the complexity of an idea into an object was more frequent among artists, painters. More recently, above all thanks to new technologies, this possibility has spread quite a lot. I myself have made forms that were always there in my drawings, but until a few years ago they had to remain on paper…

Like most contemporary designers, today your ideas become reality thanks to software. The computer has been the sole driving force of all these directions of research in the field of design. I get the feeling that much of contemporary production has moved away from tactile sensations and toward geometry. What’s your position on this?

For me construction by hand is very important, even if the industrial process is fundamental. In the products I design for Slamp, for example, I try to emphasize a certain sensation of craftsmanship, though the manufacturing process is industrial. In my way of designing there is also a part of me that is like a child, when I used to cut out pieces of paper with scissors to create imaginary figures. I like to insert a bit of my history in the object. Other works of mine, instead, strive for the exact opposite. The Zante lamp is a totally handmade object, but it aims at the perfection of the industrial product: the crafted object gives up its natural degree of imperfection and becomes perfect. A strange paradox. The viewer who observes the Zante lamp has no idea of how much ability is needed to produce such an object by hand, without a mould.

Should a design object be perfect or imperfect?

That’s a strange question. I can answer by saying that a Japanese vase needs imperfection to be perfect…

What relationship do you have with companies and, in general, with whom do you produce your objects?

The culture of the company with which I’m working is fundamental. I like to have a direct relationship with the people who will concretely make the object. If I go to Venice I talk directly with the master glassmaker, at the glassworks. At Poltronova I directly discuss things with the upholsterers and the saddlers. It is thanks to the craftsmen, and their experience, that I can experiment with new solutions. I constantly learn new techniques, new skills from them.

Much of so-called “design” is done by the craftsmen who work inside companies, though they nearly always stay out of the spotlight…

True. The role of the craftsmen is essential, just like that of the entrepreneurs who guide the companies: they are the ones who choose which path to take.

Nigel Coates, Click Clack, Scubism collection, 2008. Design for Fratelli Boffi.

Speaking of entrepreneurs and owners of companies, have you ever been hampered by their choices?

A company asks you to do a project. What the designer does is to try to explore and fully understand the needs of the company, looking for a compromise between his own taste, his own research, and the needs of the manufacturer. Business needs, obviously. The encounter between the designer and the company generates benefits for both. In general, as a designer I avoid presenting myself as the solution of all the client’s problems. If anything, I would say my forte is that I am capable of listening very closely to companies.

To use the definitions of Donald Norman, we might say you are more an “Emotional Designer” than an “Industrial Designer.”

Yes, but what is the design industry today, what does it produce? Besides objects, it produces emotions. Just look around. What do you see? Emotions, narratives, dreams. An object has to have a function and, getting beyond the lesson of modernism, it has to transmit an emotion, tell a story. And the emotion the designer wants to transmit has to be consistent with the values of the company. This is design. If there is no harmony between the values of the company and those of the designer, it all gets more difficult.

Nigel Coates, Faretto Doppio, 2011. Design for Slamp.

Certain companies don’t seem to be willing to take risks on new projects. In your view, do they avoid that for purely commercial reasons, or because they are not interested in change, in renewal?

What I have learned with Slamp, where I am the artistic director and therefore have a responsibility with respect to the company, is that all the objects have to have a certain percentage of “Slampness.” This means they should be recognizable as “Slamp products” and, at the same time, they have to have original details, new atmospheres, different styles, case by case, capable of reflecting the evolution of the tastes of the public. To achieve this result the designer, the company management and production have to be tuned to the same wavelength. First I start with an idea, but I don’t immediately communicate it to the client or the company, because it has to settle, to reach the right degree of ripening. Then, once it’s been revealed, the idea is subjected to modifications and adjustments, but without depleting its distinctive qualities, its character. Character is what generates desire.

At the start of your career your design was sensual, enveloping. Over the years it seems to have become more essential. Today, with a few signs, you communicate strong emotions.

I’ve understood that to communicate something you can also avoid pushing yourself every time to the limits of forms. And I have understood that design is not like writing a thesis: it has to have lightness, be friendly, it doesn’t have to accumulate too many meanings. An object cannot capture and transmit more than a certain quantity of emotions. My studio has changed, too: at the beginning it was chaotic, today it is very orderly, very clean.

You head the architecture department at the Royal College of Art. What do you teach your students?

I try to teach them the capacity to understand and interpret the times, the epoch in which they find themselves immersed. They have to learn to critically reflect about what surrounds them. I detest the idea that they can make architecture according to the fashions of the moment, by copying the work of the most famous architects. The students have to learn to think on their own, they have to identify their own path, to understand the world, with its contradictions, its conflicts, its moments of joy and beauty. We try to make them permeable to signs of humanity. All the signs of humanity. This is what we try to do at the College. Given the fact that their study projects have little possibility of being built, we stimulate students to identify a sort of truth of the design method, to imagine worlds, spaces, realities, stories capable of hosting their ideas. It is the vision that makes the difference, the capacity to direct the imagination toward one’s own desires. To develop such an approach is more important than learning the history of architecture in an academic way. At the College there are no theories to learn by rote. The students have to learn to grasp the possibility of the project, which is the possibility of change, of movement. Movement is transformation, evolution, and architecture is movement of space, inside space. Making architecture, making the city, means knowing how to direct this movement, this story.

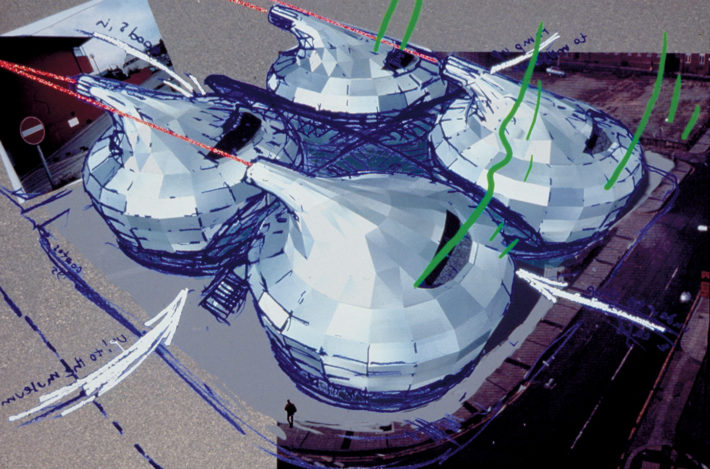

Nigel Coates, National Centre for Popular Music, Sheffield, drawing, 1998. Courtesy: Nigel Coates Archive.

What is the story we are living today, from an architectural viewpoint?

Today the concept of architecture and design connected with narration, as I conceived it at the time of the magazine NATO (Narrative Architecture Today), is at the center of conceptual speculations that don’t seem very clear. The architect is, or should be, the first one to comprehend in what direction the city is evolving, and the people who inhabit it. This evolution happens according to two space-time models. One is linear, progressive, it develops over the long term, while the other is extemporaneous, explosive, it represents the break point between two linear cycles. At this moment, I think we are in the middle of an explosive phase, a break, in which the architect is increasingly fascinated by the territories at the borders of his profession, and less and less involved in the matter that is the distinguishing characteristic of his discipline: space. So I think that to change the narrative trail of the future a bit, the architect should refamiliarize with the element of space, returning it to its status as the focal point of his projects. Whether they have to do with objects, architectures or cities. Space should be something to offer to the world. Recently I have worked more on design than on architecture, but now I think the time has come to go back to shaping the space of our cities. And thus to create a new narrative.

Nigel Coates, Caffè Bongo, Tokyo, 1986. Photo: Edward Valentine Hames.