5 April 2013

In response to great demand, we have decided to publish on our site the long and extraordinary interviews that appeared in the print magazine from 2009 to 2011. Forty gripping conversations with the protagonists of contemporary art, design and architecture. Once a week, an appointment not to be missed. A real treat. Today it’s Jasper Morrison’s turn.

Klat #04, spring 2011.

Jasper Morrison is the sort of guy who would much rather stay in a rundown hotel than a designer one. “It’s a question of atmosphere,” he explains, “designer spaces make me uncomfortable.” Others may share this view, but it is somewhat surprising to hear such a comment from an industrial designer, and a very well-known one at that. The fact is that in the era of Designer Stardom, the super-sleek, fashion-oriented types who would wish to be spotted only in ultra-stylish places have sort of become the norm. And within such a panorama, Jasper Morrison definitely stands out of the pack. Professionally for his clean, almost austere (and often slightly ironic) designs; and personally for being someone who is proud to admit his love for all that is ordinary. The adjective “normal” is a great compliment for Jasper Morrison. In his almost twenty five year-long career as a creator, he has designed all sorts of things: furniture, lighting systems, bathroom ranges, electronics, home and fashion accessories, and even urban and transport systems. And despite the massive amount of work produced, the fifty one year-old Brit has never developed a “signature style,” an iterative attention-grabbing form to be easily applied to all product categories: something that so many companies actively look for as a marketing stunt, and that so many designers are only too pleased to provide. Naturally quiet, openly critical of the marketing-driven approach to the profession, he certainly does not owe to PR the fact that he has gone a long way since the time when, aged sixteen, he decided to become a designer. Initially driven by some sort of romantic dream (in which he spent the days “walking the streets looking for inspiration”), he was never too keen on schools that applied a traditional “problem-solving approach” to design, and he grew thanks to his extreme respect for the past and through his curiosity about all that went on around him. And, today, he has no doubt: the highest possible value that design can strive towards is normality. Or, rather, supernormality. “The Super Normal object,” writes Jasper Morrison in Super Normal, the book-catalogue of the 2006 exhibition of the same name co-curated with Naoto Fukasawa, “is the result of a long tradition of evolutionary advancement in the shape of everyday things, not attempting to break with the history of form but rather trying to summarize it, knowing its place in the society of things.”

“Normal is more common in the world of totally anonymously designed things, but it is also possible in the world of designer signatures: this is not only preferable but it also seems to offer a whole new world to design.” These are your own words, expressed in the catalogue of the Super Normal exhibition. How would you describe this “whole new world” that normality can offer to design?

Design is better when the designer is not concerned with writing his signature all over. Just as signature objects often under-perform, so do designer environments, usually because the creative ego is too evident. Sometimes it happens even if the designer did not intend it to occur. Once a Sushi bar near my office in Paris purchased forty of my Magis Air-Chair and put them out on the pavement. They were all pink! The moment I saw them, I felt a wave of shame and guilt: they certainly grabbed people’s attention, yet the color had taken over and the chair had lost meaning. Noticing this environmental pollution, I started trying to eliminate the “designer” element in my work and giving priority to the performance of the object. After all, if you are looking to buy a new chair do you care more about who designed it or about whether it’s comfortable and it fits well into your home? Creatively speaking, suppressing the ego is surprisingly good for creating! The goal is Normal, Super Normal. With this I mean the opposite of Special in terms of forms and materials because objects conceived in this way tend to perform better in daily use over the long term, which makes them better designs.

You have often quoted your grandfather’s modernist study and an Eileen Grey exhibition at the V&A as your early inspirations for design. Yet you also admitted to a fascination provoked by Memphis’s first exhibition in Milan in 1981. Hardly a “normal” style there! In which way have these two opposite approaches to design impacted your creativity?

The England that I grew up in was very dark and kind of over upholstered. Every interior had curtains and carpets. My grandfather, though, had one single modern room in his home. His Braun record player, his white shag pile carpets, the wooden floor and the furniture certainly made an impression on me when I was little, although more subconsciously than anything else. So when I saw, much later, an Eileen Grey exhibition at the V&A I was first able to connect that impression with the modernist design language and had the impression I could understand what she was doing. Memphis, on the other hand, was a provocation rather than an inspiration. It was the opposite of everything I had been taught design should be. I had been going to the Milan Salone a few years before the Memphis launch, and already seen Studio Alchimia, which was more radical than Memphis. But it was the contradiction of the commercial glitz of Memphis combined with the almost completely impractical nature of their products that proved more shocking. With Memphis, you were in one sense repulsed by the objects (or I was!), but also immediately freed by the sort of total rule-breaking. What I did after Memphis was to concentrate on an opposite theory that design should be practical and available. If Memphis had not happened it would have been much harder for me to find my way.

Jasper Morrison, door handle, mod. 1144, 1990. Design for FSB.

Practicality and availability. Is that why you have mostly worked for industry rather than on self-productions?

While I was still a student, having no access to industrial production, I simulated it with small production runs of some of my work. That was hard work and not very profitable and I knew that I should aim at being just a designer and at finding manufacturers. There were two people in London in the eighties who were producing on a small scale: Sheridan Coakley (who set up the high-end furniture store SCP in 1985) and Zeev Aram (of the Aram Store and Gallery). They took up some of my designs. Then, some of my work was published in Domus magazine in an article by Manolo De Giorgi, and this came to the attention of a German door-handle maker, FSB, who contacted me, followed a little later by Cappellini and Vitra. It all sounds so easy, when you make a summary of it, but it wasn’t. I worked very hard at it.

Did you have a design vision when you started? And, if so, how has that evolved through the years?

My early notion of being a designer was a romantic one. I thought that it involved getting drunk every night and spending days walking the streets looking for inspiration. Travelling, talking to people, and being open to what was around was fundamental to inspiration, while sitting in front of a white sheet of paper was the death of creative thinking. I wasn’t completely wrong and I still believe that design entails a kind of reprocessing of what already exists, of evaluating previous examples of everything and trying to improve them, and that this can only be done by physical experience rather than academic study. The most exciting thing for me is to see how people live, what they live with, and the influence objects have on everyday atmosphere: that’s what gives me the impulse to do new things and to try to get them right. But these days I am a lot more Zen about inspiration, and I don’t make any conscious effort to find it: I try to be very spontaneous in the design process, making decisions very quickly, based on instinct and experience.

You graduated in Design at Kingston Polytechnic Design School and got an MA from the Royal College of Art. How do you feel about your education and what do you think a good school should provide?

They were both good schools and I learnt a lot, but what was missing was hard information on industrial processes. I think it was missing because most of the teachers didn’t have the experience of designing for industry. When I left school this was the hardest knowledge to acquire. Maybe these days with the Internet it would be easier, but I still think design schools should focus more on the technical aspect of the job than the creative one.

What was your very first industrial design project that made it into production? And how often, working for the industry, do you feel that you need to compromise on the design side?

My very first truly industrially manufactured product was a door handle for FSB. After the concepts were featured in Domus, Jürgen Braun wrote to me saying that he thought my design was suitable for production. At the first meeting he made me immediately aware of the need to accept certain compromises. The proportion of my handle, for instance, had to change dramatically in order to be compatible with their existing system of fitting to the spring mechanism. I agreed because I thought that as a designer you should “bite the bullet” and accept production requirements. But the change killed the design. To date, I’m still not sure how I could have saved the project but it was an early and powerful lesson. There are always moments of compromise in the development of a design, and it’s important not to see one’s project like the Titanic hitting the iceberg. There’s usually a way to turn the need for the compromise into an opportunity to make the design more real, without losing its nature.

So Jürgen Braun was the first to believe in your talent. Yet the world remembers mostly the elective affinity between you and Giulio Cappellini. How did this relationship start and in what way did it impact you, both professionally and as a person?

Meeting Giulio Cappellini was one of the most influential events of my career. He had already started to build a strong reputation for his company, working with Rodolfo Dordoni and producing Kuramata’s designs. He was the first Italian industrialist to take on foreign designers, and luckily for me I was one of the first he chose to work with. I think Giulio saw the Domus article on my early work, and was interested in the Thinking Man’s Chair, which was the first piece he chose to produce. This was in 1986, two years after leaving college, and it’s hard to express how incredible it felt to be working with an Italian company. I’d only ever heard of one English designer working in Italy (Rodney Kinsman) and to say it was my ambition to be the second would be an understatement…

Jasper Morrison, Thinking Man’s Chair, 1986. Design for Cappellini.

Many young designers say that it is extremely hard to be noticed by companies today. Do you think it is harder now than it was then?

I’m sure it’s much harder now, because the competition is so extreme. To give you some idea, in the eighties the Milan Fair was a fraction of the size it is today and most design students in England had never heard of it. I was one of a very few who took the trouble to go to Milan every year. At that time, the goal of every student, including myself, was to get a job in a design studio, and the idea of earning a living with your own studio was an option for daydreamers. So at the end of my first year at the Royal College, as I was frustrated with the slow schedule of the course, I went to Milan and visited many design studios, including Sottsass’ and George Sowden’s. I don’t blame them for not employing me, I think I was not the right “material” to be a design studio employee: I could think well enough, and have plenty of ideas, but carrying them out was not my strongest card. I could work, but only on projects which enthused me. Andrea Branzi was the only one with a proposition: if I came to live in Milan he said he would find some work for me. His offer was very encouraging: hearing that someone like him might give me work gave me enough confidence to consider opening my own studio. In any case, in the end I got a scholarship to study in Berlin at the Hochschule der Künste and I decided to go for it. And after that, I opened my own studio.

Companies clearly trust you in that they allow you to experiment with technologies. In what way were for instance the Low Pad chair for Cappellini and the Air-Chair for Magis innovative and how did the two projects develop?

Low Pad started out very differently to how it ended up. The first prototype was a very poor project, but the random association of the molded rubber sole of a shoe and the shape of an airport seat, combined with the technology of car-seat manufacturing, changed it into something more interesting. The Hi-Pad chair (which I think will be the more lasting design) followed very soon after, during a lunch with Giulio Cappellini. I drew it on an empty packet of crostini and we made a prototype overnight, about a week before the Milan Fair! TheAir-Chair was quite different. The technology again came from car manufacturing (interior door handles) and Eugenio Perazza explained it to me and gave me a length of molded tube, like a bone-hollow in the middle. I designed the chair from the leg up based on the oval section of the tube sample and on creating a continuous tubular structure with the back and seat filled in. It has some affinity with the Plywood Chair which Vitra produced much earlier.

You often design technological items: for Muji, Samsung, Rowenta, Olivetti, Punkt. What is your relationship with technology?

I like to imagine that my office could take on any design job, on any scale and in any field of production. The process of designing a chair is different to designing a telephone, but it involves the same kind of practical thinking and decision-making. The more technical the product, the more complex the process of designing it, but otherwise there’s not such a big difference. If you can design a chair you can also eventually design a wristwatch or a pair of shoes.

Which is exactly what you did for Camper. Isn’t the very basis that makes fashion what it is (its seasonal approach, for instance), miles away from your design approach?

I like companies like Camper and Muji: they make things available and affordable and there is a generosity in their offering that you do not find in the luxury goods business. Why did I say yes to the proposal of designing a pair of shoes? Because I felt I could, and because I appreciate the brand, because I saw the chance of turning the shoe into some kind of standard that can be revamped over many years. Certainly, I designed the Camper shoe to last also in terms of looks but I may be wrong, and the tides of fashion could wash it away…

Jasper Morrison, The Country Trainer, 2011. Design for Camper.

What is, to date, the project that has given you the most challenges and how did you tackle them?

The biggest challenge and perhaps the biggest failure has been my collaboration with Samsung. Even if some of the projects were produced, the proportion of results for the effort applied was very poor. I was unable to deal with the pyramid of management inside the company. I was not prepared for the corporate machine and its unpredictable decision-making processes and my projects lacked dollar signs in their eyes… But I learnt a lot from it and working with Punkt. on the telephone, although smaller in scale, seems to allow for better results in terms of design quality and future potential.

What are you working on at the moment and for which brands?

I am working on quite a few chairs! One for Maruni (the Japanese company whose art director is Naoto Fukasawa) and one for Muji. For Magis, I am developing a wire garden chair which began with the observation that the best products in this typology are almost transparent and consist of fine metal structures. For Vitra, I am continuing on the Hal program that we partly showed at Orgatec. We spent almost three years developing the shell of the chair to provide the optimum level of comfort and dynamics in use, to be comfortable both in active and passive use. It’s also I believe the first shell to be fully recyclable, as the fixing points within the shell are plastic rather than metal. For Alias, I am working on yet another chair which is quite simple as an idea, but finding the right industrial production and assembly method is quite a challenge and I am not sure whether we will make it for the next Milan Fair.

You have worked with James Irvine on the Progetto Oggetto collection for Cappellini. With Naoto Fukasawa on numerous occasions. Why do you like working with fellow designers?

Many of my closest friends are or have been designers. I’ve known James since 1980 when we went to art school together and Naoto has become a good friend since we did the Super Normal exhibition. I enjoy the dialogue that comes from working with and meeting other designers, to discuss specific work (I often see Naoto and Konstantin Grcic, for instance, since we all work for Muji) or just meeting for dinner. I think that the profession brings us close, because we spend our days in similar ways, and probably have common goals. So I enjoy talking to designers even if our work may seem to be very different. I have been recently discussing projects with Martí Guixé and a few years ago I became a good friend of Jaime Hayon after sharing a plane trip: he was sitting next to me wearing blue spectacles and red shoes and even under those circumstances we became good friends! Sometimes I spend the whole day talking with my assistants about life and how things should be, and it’s a pleasure.

Does that mean that you also give room for creativity in your studio to your collaborators?

What I like most in the daily routine are indeed the discussions we have in the studio. They are a vital part of the development of any project. We test everything we do through these discussions, so while it’s typically me who initiates the project, developing is definitely a team effort.

Let’s now talk about a couple of controversial issues. In 2000 you accepted a commission from a museum in the Provençal village of Vallauris to produce limited edition ceramics made by local artisans. Due to the “industrial” look of the results, the European craft community was outraged. “Why work with the ancient skills of the Vallauris potters,” railed an editorial in one craft magazine, “to make something that looks as if it came from a factory?” Can you describe this project, why you decided to carry it out and how you felt about the comments?

I am not particularly proud of the results of that project and I partly accept the criticism. But if craft is the goal then why not invite a craftsman? Although I like the idea of people making things by hand out of necessity or because they couldn’t be made better by machine, I am not much of an enthusiast for the modern day embodiment of craft. I can’t see the point in making things by hand that will cost more and be less available. Isn’t it better to attempt to make industrial objects that have meaning to us than to pretend that we can only relate to the handmade object?

I am curious, in the light of what you just said, to know what you think of the whole designer limited edition craze…

It has its place, just as haute couture does.

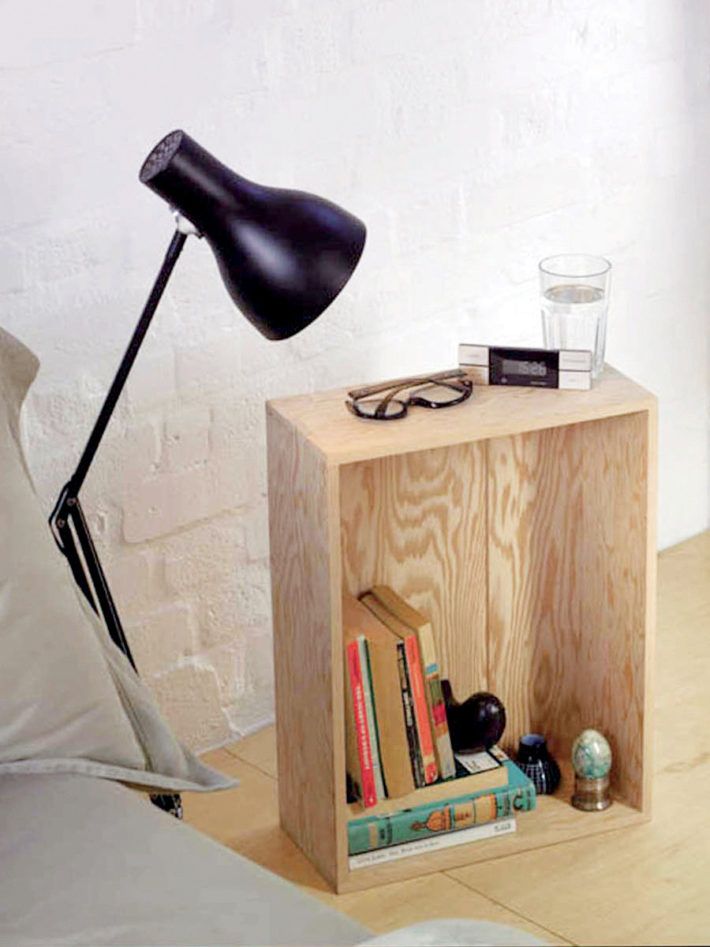

Another controversial project of yours was The Crate for Established & Sons. Can you tell me how you came to develop it and why?

It’s a very simple story. When I moved into my Paris apartment, the builder left behind a wooden wine crate that he’d used to store tiles. I cleaned it up and used it as a bedside table. Two years after that entirely practical gesture, I realized it was a design, maybe even a very good one. Established & Sons asked me to do something and I proposed they should remake The Crate as a piece of furniture. Fortunately they believed in the idea and it was shown at the Milan Fair, provoking a kind of outrage I hadn’t ever encountered before. The Crate I designed for Established & Sons is almost identical to the original, but it’s made from higher quality wood – Douglas fir, rather than splintery pine – and the joints are stronger. I only proposed it as a design, because I had discovered how practical it was and how nice it was to have beside your bed. Some people got it, but many missed the point completely.

Jasper Morrison, The Crate, 2006. Design for Established & Sons. Photo: Peter Guenzel.

What do you think of the Salone in Milan and of the proliferation of the Design Week phenomenon all over the world and the related media attention? Does all this actually help design?

I have started to call the Milan event the Salone del Marketing, which I suppose is an answer to your question! As for the various Design Weeks, they have their role in bringing awareness to the public. Overall, with regard to design communications, it’s the message rather than the messenger that may be at fault. In the case of some design magazines, however, I think it’s a case of the messenger dictating the message. I don’t subscribe to any design magazines except Apartamento.

The environmental issue is certainly a great one to tackle for humanity as a whole. Don’t designers actually contribute to making more and more stuff that people do not actually need?

I think the designer and the manufacturer have to do whatever they can to design and make products that last. At the same time, consumers have a responsibility to look for products that last, and are not just passing fashions! The media should also make more of an effort to understand and promote better products instead of taking pictures of twenty of them because they’re all the same color!

Do you have any advice for young designers today?

Work hard and keep your eyes open. What I mean is that there are qualities that an academic education is not able to provide. The technical knowledge, to start with, but above all the habit of looking which I got from browsing through books and from wandering the streets. In retrospect, I think that this was my education. So now if I ever teach I try to communicate that the most important thing is to learn to use your eyes, then judge and evaluate objects, situations and problems.

Jasper Morrison, DP01 Telephone, 2010. Design for Punkt.

Jasper Morrison, DP01 Telephone, 2010. Design for Punkt.

Jasper Morrison, Plywood Chair, 1988. Design for Vitra. Photo: Studio Frei/Vitra.

Jasper Morrison, Air-Chair, 1999. Design for Magis.