22 April 2013

In response to great demand, we have decided to publish on our site the long and extraordinary interviews that appeared in the print magazine from 2009 to 2011. Forty gripping conversations with the protagonists of contemporary art, design and architecture. Once a week, an appointment not to be missed. A real treat. Today it’s Francesco Vezzoli’s turn.

Klat #01, inverno 2009-2010.

Interviewing Francesco Vezzoli is no simple matter. First, because he is a nomad-artist, by vocation or necessity, so there is no studio where you can show up with your list of questions and your tape recorder. You have to chase him through the web, often in very different time zones. But mostly it is because Vezzoli is interested, above all else, in the media, in their hidden mechanisms and their power. And in his working career he has learned to know and manipulate, with great skill, the widest range of aspects. The mechanism that operates around the creation of a success is his foremost material for observation and research. In the end, even when Vezzoli chose embroidery, he was unveiling the iconographic baggage of some of the stars of his and our image-bank. From the performance of Veruschka at the Venice Biennial directed by Szeemann in 2001, to the 2007 edition – when Padiglione Italia was partially filled with large screens that showed the rhetorical, masterful images of Sharon Stone and Bernard-Henry Lévy, the actors in Democrazy –, Vezzoli’s work has never lost sight of its true objective: the construction and de-construction of a public persona. Whether it’s a model from the golden age, an aspiring inhabitant of the White House or a female art icon, everything depends on how one is able to get his own 15 minutes of fame, and then to transform them into something more stable and definitive. It is no coincidence that an integral part of the work of Francesco Vezzoli lies in convincing entertainment celebrities to participate in his works. We are not talking so much about the present situation, when being called on by Vezzoli for a video has become something of a must for movie stars. Just think about the early days, when Vezzoli managed to convince Helmut Berger to kiss him for a remake of Dynasty, or Silvana Mangano to embroider in the video entitled OK, the Praz is right! From that moment, when the embroidery was the private, uncool flip side of silver screen fame, to get to Sharon Stone took participations at three Venice Biennials and one Whitney Biennial, solo shows at the New Museum of Contemporary Art in New York, the Castello di Rivoli and Fondazione Prada, and a Hollywood production of Trailer for a Remake of Gore Vidal’s Caligula. In the meantime, Vezzoli’s real focus has emerged, with its total lack of commitment, irreversibly seduced (or corrupted, according to some) by his fascination with fame: to reveal the wily game behind the winning image we finally see. A focus that has allowed him to construct a magnificent allegory of fame and power, of their patient construction and inevitable decay.

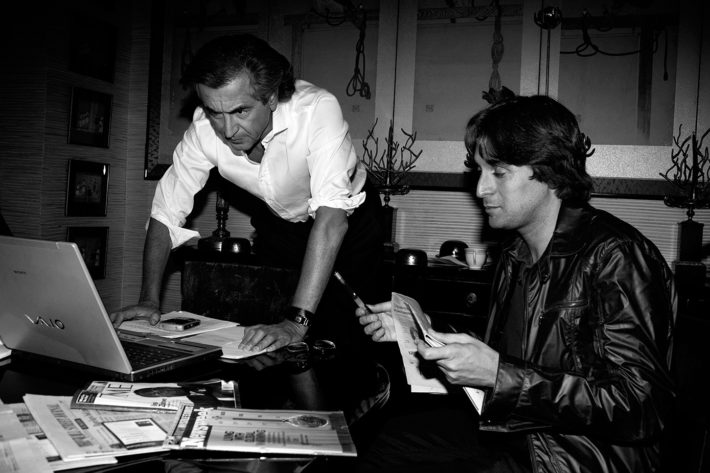

I’d like you to begin by talking about how the creative process of a contemporary artist works, since you might be seen as the epitome of that role. No studio, constant travel, ideas assessed with a collaborator with whom you have worked for many years.

I am a nomad artist, I go wherever I feel the need to go. I have no studio in a specific city, not even a house. Everything I earn gets reinvested in new projects. In this continuous movement, of course, I also need at least one stable reference point. Luca has worked with me for many years, we were classmates in high school, his role is to be an editor: he keeps the archives, gathers materials and information. I tell him my ideas and we discuss them. The stimuli for projects and works are filtered, evaluated, simplified, to get a clearer view.

Francesco Vezzoli, Trailer for a Remake of Gore Vidal’s Caligula, 2005. Courtesy: Castello di Rivoli, Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Rivoli (Turin). Photo: Matthias Vriens.

So the final projects are the result of intense discussion between two different ways of observing a theme, an idea.

I come back from my travels full of stimuli and ideas, and Luca helps me to put them into form. This also happens in the sphere of publishing: our work together can be compared to what happens in publishing houses. On the one hand there is the writer who creates his book, on the other the editor who monitors the work, to make sure its parameters are respected.

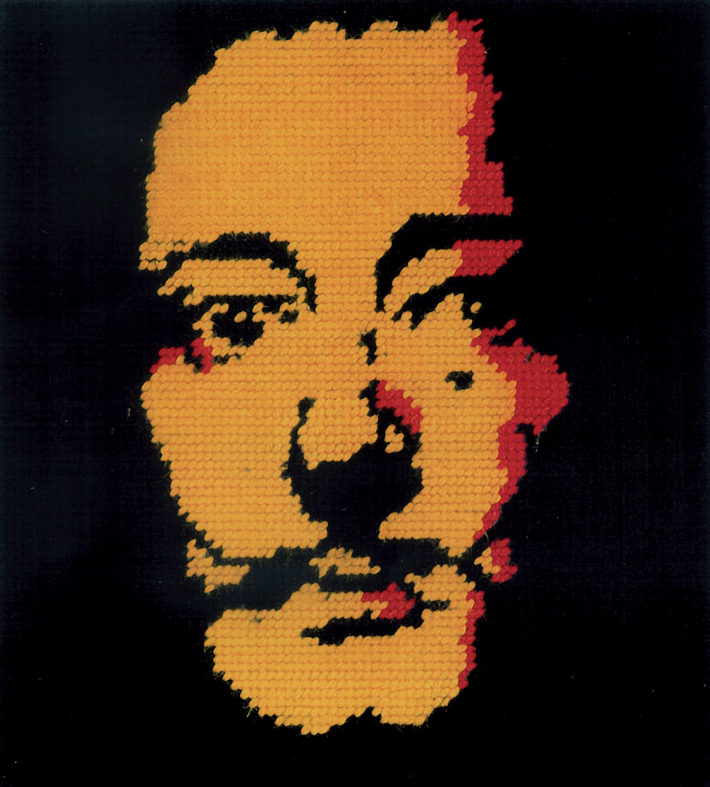

To approach the overall body of your work, which is quite vast at this point, I would like to begin with the technique that first made you famous: embroidery. The technique you are still associated with most, at least in Italy, perhaps. What is your experience of it? Do you think it is still timely? Does it still interest you, or is this tool for overcoming solitude no longer a part of your present world?

The technique is still mine, I chose it initially because for me embroidery represented a kind of zero degree of painting. There is painting, then watercolors, then embroidery: the least noble, most everyday form that can be taken by figurative technique. Furthermore, there is a psychosexual subtext of great impact, especially in Italy: my works are often interpreted as a part of gay iconography. Later, I understood that this interpretation had more to do with a lack of critical discussion of the subject than with a specific analysis of my artistic personality. On the Italian scene there are few artists who have approached this type of imagery. Thinking through the classic genealogy of Burri, Fontana, Arte Povera, Transavanguardia, no one has directly addressed this subject. My embroidery is a metaphor, or even a parody, of a typically gay language. So inside a very macho artistic tradition, this aspect of my work remains an original node, in both positive and negative ways.

Francesco Vezzoli, Time, Clock of the Heart (after Ingres), 2008. Courtesy: Galerie Yvon Lambert, Paris.

Let’s talk about the curators with whom you have worked: they include some of the most important in recent history starting with Harald Szeemann, who invited you to your first Venice Biennial, where you presented the famous performance with the model Veruschka. Did he give you confidence in your work?

Actually the first curator to believe in my work was Paolo Colombo. I did my first things with him at the Centre d’Art Contemporain of Geneva, he had chosen me for an exhibition entitled Fatto in Italia. At the time I was not officially an artist. Colombo was the first person that believed in my work. Szeemann came later.

How did that happen?

At the Venice Biennial in 2001, Szeemann chose and showed the embroidered pieces. There were also videos, but he focused, paradoxically, on the embroidery. I say paradoxically because that was the aspect of my work that the critics, or at least some of them, always seemed to find most problematic.

I had a very serene relationship with him.

That was a fundamental opportunity for your career…

I remember that everyone talked about your project. Definitely. Participating at the Venice Biennial is an extraordinary opportunity for an artist, to make his work known to a very wide range of people. When I took part at the Biennial curated by Harald Szeemann very few people, even among sector professionals, knew who I was and what I was doing, so it was very important. The presence of Veruschka who embroidered her own portrait triggered very strong reactions. I remember the director of a museum who attacked me, saying that my work was based on exploitation… Even the most negative reactions, for me, are strong stimuli, so I prefer exhibitions in museums instead of solo shows in private spaces, like galleries for example.

Francesco Vezzoli, Self-portrait with Vera Lehndorff as Veruschka, in collaboration with Vera Lehndorff and Gianpaolo Barbieri, 2001.

Is there any curator who has particularly stimulated your work?

I really enjoyed working with Chrissie Iles, the curator at the Whitney Museum, who is very well versed in the history of cinema and video art. She is an extraordinary person. Into the Light, the exhibition she curated on American video art, gave me an opportunity to see, on film for the first time, the split-screen video by Warhol, Lupe, which then inspired me to make The End of the Human Voice with Bianca Jagger. Chrissie Iles is also a person who reassures me in my work, because she doesn’t have problems regarding the presence of stars in my projects.

Do you really think that in the United States anyone has problems about the presence of celebrities in your videos?

Let’s say my work tends to provoke strong reactions. I like that aspect, I’m proud of it. But at times the process gets complicated, triggering a form of resistance, of irritation.

Tell us about the different reactions to your videos or your installations. I imagine there are big differences between generations, for example, in the comprehension of your work.

Where the younger generations are concerned, the appreciation or irritation with my work has nothing to do with the use of celebrities. For a person who is 25 years old the presence of a star in one of my videos is just a fact, it is not seen as a challenge to critical thought, as in other circles. I like this, but it also upsets me at the same time.

Why?

Because I realize that the presence of a star no longer suffices to cause friction or to provoke a strong reaction. At the same time, this means that stars are now a vehicle of meaning, a contemporary symbol, in themselves. So I guess I got something right!

Francesco Vezzoli, Democrazy, set, 2007. Photo: Matthias Vriens.

Are there big differences between the reactions to your work in Europe and the United States?

Definitely. One symptomatic case was that of the double exhibition of Trailer for a Remake of Gore Vidal’s Caligula. It was shown first at the Venice Biennial and then at the Whitney Biennial in New York. In Venice everyone who entered the room where the video was projected seemed to be very amused. In New York, on the other hand, absolutely no one laughed.

Why have you moved away from the United States?

At the moment I don’t feel any need to settle in America. I move constantly, to places that attract me. The Americans seem to be particularly affected by the economic crisis. We Europeans are historically accustomed to coming to grips with economic and social problems, with financial upheaval.

Francesco Vezzoli, Surrealiz (Who’s afraid of Salvador Dalí?), 2008. Courtesy: Gagosian Gallery, New York.

In relatively recent projects you have concentrated on understanding the mechanisms that control American society and politics. For the next to the last Venice Biennial, where you were invited by Ida Gianelli, you made Democrazy, a fake TV ad for the primaries. Looking at it now, one year after the elections with the most intense participation in recent history, which led to the election of a candidate, Barack Obama, few observers thought could win, at the outset, Democrazy seems particularly apt.

In that project I was interested in understanding how the mystique of a persona is constructed, to the point of becoming The One: the man or the women for whom everybody wants to vote. To understand, in short, how the teams work when they manage, through the choice of a phrase, a slogan, a look, to gain the approval of millions of voters. Another factor I started with was the consideration of the growing “Americanization” of Italian politics: I wanted to look at the United States, where entertainment and political mechanisms are closely linked, also to understand Italy. From the pilot for a talk show that would never go on the air, like I comizi di non amore, to a trailer for a film that would never be made, it seemed perfect to do an election-campaign advert for an imaginary presidential candidate.

Given this interest in political communications and the time you spend in the United States, what was your impression of the last US presidential election?

I am happy about Obama’s victory, though I don’t really share the general enthusiasm, because I don’t think any profound changes will happen. The corrupt nature of power has remained identical since the beginning of human history. Of course the Obama campaign was planned perfectly, under the extraordinary patronage of someone like Oprah Winfrey, the most powerful woman in American journalism, and the results were exceptional.

The close relationship between entertainment and politics seems to have been partially reproportioned in this period of crisis, that has led to an effort to be more pragmatic, to look at results. Do you think this moment of global recession will also involve your work in some way?

Absolutely not! My work involves reflection on media and it seems to me that Hollywood and television are the only industries that keep on functioning!

Speaking of this relationship with the entertainment industry, you now have a show in which you are combined with a personality who understood, very early on, the importance of taking care of that side of his work…

It is a show that opened in September at the Moderna Museet of Stockholm, entitled Dalí Dalí Featuring Francesco Vezzoli. It is organized like a normal show on the Surrealist master, that then turns into a concise, ironic retrospective, in a Surrealist key, on my work.

Francesco Vezzoli, Salvador Dalí, 1998. Private collection.

Looking at your career, it is easy to imagine that you might be interested in Dalí. Did you choose organize this “encounter”?

Actually, as opposed to what usually happens, it was not my choice. The curators, John Peter Nilsson and Caroline Corbetta, came up with the parallel between my world and that of Salvador Dalí. For me, this was a dream come true, because Dalí has always fascinated me as an artist. And I am very interested in him, above all in relation to Andy Warhol. In the last phase of his life, Dalí undoubtedly influenced Warhol, also because they knew each other. In this relationship we can see the birth of the idea of the artist as a brand, appearances on television programs, the creation of fragrances, advertising promotion. Recently, this mutual influence has been the focus of study in the United States and Europe. I’m thinking about the exhibition curated by Eva Meyer-Hermann in London on the relationship between Warhol and television. It is a significant inversion of the trend, because until now the later Dalí, with his dark side, has not been taken seriously by critics, especially in Europe, where rehabilitation was hampered by ethical problems. For me, the idea of being paired with Dalí is a very great honor, even more so in an absolutely impeccable setting like that of the Moderna Museet.

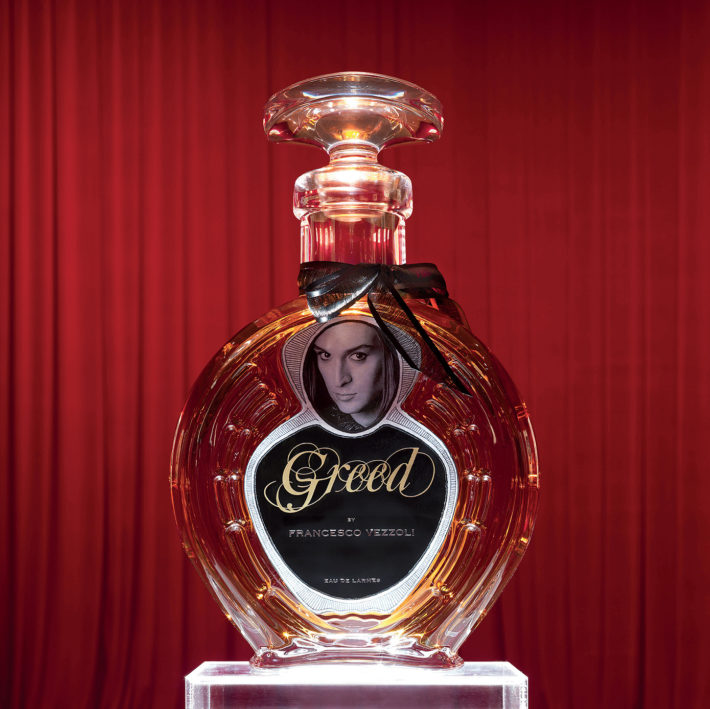

I’d like to talk about your recent show at the Gagosian Gallery in Rome. Your focus on the world of media was at the center of the Roman show, where behind a project presented as the launch of an artist’s fragrance, there lurked reflections on femininity, the pleasures and difficulties of female existence. Lee Miller, Frida Kahlo, Louise Nevelson, Eva Hesse: why did you want to transform the Gagosian Gallery into a Pantheon of 20th-century female artists?

I was interested, as often happens in my work, in shuffling the deck and using extremely different women artists as testimonials for my perfume, combining the sacred and the profane. I discovered, while I was researching the project, that the range of choice was actually rather limited: I thought I would have problems choosing, but once I had eliminated the women who worked together with their male partners, and the very many “muses”, only about ten protagonists remained. A profoundly macho dynamic has drastically reduced the number of female artists with a strong image in history. Female icons in art history are so few and far between that they can all be gathered in my show in Rome.

At the center of the Gagosian Gallery, to complete the main installation, visitors found a real bottle of perfume, Greed, which I think might be your very first sculpture…

It was precisely the specificity of the exhibition space, with its circular form, that suggested the need to create a center, by means of a sculptural feature. So what sculpture could I make, other than a bottle of a perfume that doesn’t exist? It seemed to be right in line with my previous work: trailer, spot, pilots for films and television programs, elections that would never happen. I wanted to materialize an absence, a non-existent perfume, in a circular, concrete, particularly definite place.

Francesco Vezzoli, Greed, The Perfume That Doesn’t Exist, 2009. Courtesy: Gagosian Gallery, New York.

It’s a lovely bottle. For those of us born in the 70’s, it is easy to recognize one of those giant versions they put in shop windows…

Exactly! My model was Eau de Voilette by Marcel Duchamp, a ready-made from 1921, but I imagined a decidedly less refined version, so I decided to use crystal instead of blown glass, precisely to make one of the shop-window models that were used above all in the 70’s. I didn’t want to exaggerate, making a Pop sculpture, but I didn’t want to make it so small it would become like jewelry either. I was helped by a childhood memory: precisely the proportions of those “magnums” that were once used in shops.

There was also an advertisement directed by Roman Polanski. You have always said that you do not think of yourself as a director. Is this why you decided to get another author involved, rather than handling the directing yourself?

I liked the idea of connecting with the first three videos of my career, An Embroidered Trilogy, where the directing was by John Maybury, Carlo Di Palma and Lina Wertmüller. But I also wanted to state, in a moment in which many artists from the generation before mine make very successful films – like Julian Schnabel and Steve McQueen –, that shooting video is not what interests me, nor am I very good at it. Instead, I would like to be a producer, or to work on casting: I believe that an artist, in this role, could still create real controversy, and in my opinion that is the true role of art.

Do you think contemporary art can or should still raise eyebrows?

Raising eyebrows is very hard now, because everyone is playing with a multiple, public and private identity… It’s like a role-play game and, in the end, it’s what has interested me since the start of my career. I think the only really provocative thing would be to reveal a bit of truth: there are masks, imposed by the system, and once in a while it is nice to take them off.

This desire to reveal the mechanisms that regulate the world of communication and entertainment seems even more evident in the evolution of your work. The political dimension of your research is a very important element, even in the gallery shows.

Yes, in the show at Gagosian in Rome I continued analyzing the presence of the media in our culture. What attracts me most is the element of communication inside politics. As a child I wanted to be a journalist, and now I think my work can also be interpreted in this sense. In London I saw David Frost, the journalist who managed to interview Nixon and to get him to talk about the Watergate scandal. Probably, the means utilized in that legendary conversation were not orthodox, but he was able to do something extraordinary. As a journalist, I try to get to the bottom of the subject, I try to get a scoop, even if I have to get my hands dirty: I know how to make news, putting personalities together in a grand media theater. I set a role aside for myself in the game, but I leave the social interpretations up to the others.

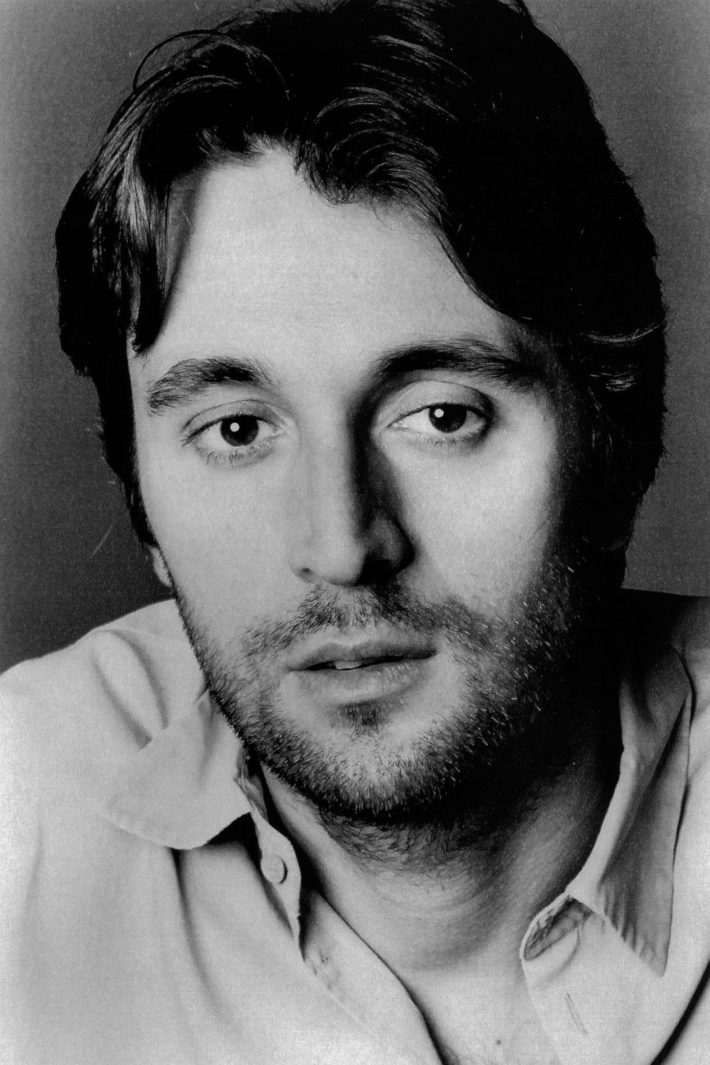

Francesco Vezzoli, Francesco by Francesco: before & after, 2002. In collaboration with Francesco Scavullo.