12 July 2013

In response to great demand, we have decided to publish on our site the long and extraordinary interviews that appeared in the print magazine from 2009 to 2011. Forty gripping conversations with the protagonists of contemporary art, design and architecture. Once a week, an appointment not to be missed. A real treat. Today it’s Martino Gamper’s turn.

Klat #02, spring 2010.

Martino Gamper, one of the most intriguing personalities in the world of contemporary design. Ron Arad has called him «a wizard, an inventive chef», while his friend the graphic artist Kajsa Stahl says he’s a «last-minute perfectionist». His method has something brilliant about it, ranging from crafts to improv to the conceptual. In all his projects, at dinner with friends,

in all his various theories, spontaneity and uniqueness

are his most outstanding traits.

Hi Martino. To define yourself, in what order should we list these terms? Designer, artist, chef…

As a profession I think of myself as a designer, but my approach to design is artistic, in certain ways. Like an artist, I can work without having a client. Not having a client can be a good thing, because you are freer, but the void can be scary too. My method has a lot to do with research, and less to do with creation, which is sort of the difference between a designer and an artist. The two spheres are set apart by the functional aspect. Art can be irrational, it doesn’t have to explain anything. On the other hand, I have to be able to define what I create and above all I want my sculptures, my objects, my furniture to be used. So to answer your question: designer, craftsman, artist and chef.

Italian by birth: Merano, 1971. Londoner by choice: you studied at the Royal College and then stayed in England. Why London?

London, first of all, for training. I escaped from Italy when I was quite young. After working as an apprentice with a carpenter, when I was 19 I left the mountains, and Italy, to explore the world. I felt isolated in the place I grew up. I love the mountains, but they don’t let you see what’s happening on the other side of their peaks.

Between Merano and Milan, where you gained experience during two years in the studio of Matteo Thun, there was the Academy in Vienna and many trips to different places in the world. I think that living in different cities, moving your thoughts in the world, has a decisive influence on a person’s character and way of being. What did you get from Vienna and the nomadism of your travels?

Vienna influenced me, it offered the great culture of Humanism, the start of crafts design, the Jugendstil, the Secession, but also the art in the 1970s and 1980s, Viennese Aktionismus, the culture of food and coffee. The experience in the studio of Matteo Thun was my first contact with industrial design. It was a useful, engaging, educational experience, because the world of work is hard to understand for someone who just got out of the academy or the university. I’d say that Thun taught me a method, but he also showed me what I didn’t want to do, helping me to find my own path, my own dimension, making me aware that I didn’t want to work for someone else, but only for myself. Before studying in Vienna I traveled around the world for two years: the United States, Central America, Guatemala, Mexico, Hawaii, New Zealand, Australia, the Philippines, Thailand. Every one of those places left me with something, it would take too long to list them all, but they all had a part in making me what I am today.

How did you choose your destinations?

I had a “round the world” airline ticket that lets you stop wherever you want, as long as you continue moving in the same direction, never backtracking, so at times the choices were obligatory. What did I learn from that trip? That the world is full of possibilities, and you are the one that has to choose. The world doesn’t make choices for anyone, when you travel you have to make a choice every day, about where to go and how long to stay there.

What does Italy mean to you? How do you see it, now that you live elsewhere?

Italy remains a point of reference, with my home, my family, a certain sense of belonging. From abroad, you can’t really understand what is happening in Italy, the media seem to only talk about superficial things or scandals, and it seems like the Italians can identify with this culture of appearances, void of meaning, tired. Actually, I think the mentality of young Italians has opened up in recent years, in search of a change the country doesn’t offer. They are starting to travel more and many of them, first by necessity and now also by choice, are looking for opportunities abroad.

What do you read to stay informed?

I read the New Yorker, the German weekly Zeit and every day I look at the BBC online, but I also visit the sites corriere.it, repubblica.it and stol.it, a Merano-based site, so I go from the world to Italy, my country.

Martino Gamper, Backside, 100 Chairs in 100 Days and its 100 Ways, 2005-2007. Photo: Åbäke, Martino Gamper.

Do you think you will ever return to Italy?

Not to live, at least for now, but there are many situations that take me there: vacations with friends, and work opportunities. And I am glad.

100 Chairs in 100 Days: your biggest show, which went from London to the Milan Triennale. The exhibition illustrates your creative capacities. Each seat has its own personality, they seem like portraits, three-dimensional collages. When I saw it I had the impression that you had infinite combinations available, to reach the design of each chair. How did you choose certain combinations instead of others? Was there an immediate creative impulse that guided you in the choice of the combinations?

The 100 chairs are finished projects, but those ideas have led to an equal number of others. The time limit made the project intriguing. I really did make them in 100 days, though not consecutive days, obviously. I enjoyed translating my ideas into a three-dimensional space, creating a sort of sketchbook.

Tell me about the titles you gave to each seat. Are they spontaneous or do they contain a key of interpretation?

I was asked to give them titles only when I began to do the catalogue for the show, so they came a posteriori. In some cases all I could do was associate the chairs with persons, humanizing them, though I had not previously thought about them as portraits. In other cases I wanted to be ironic about historical references or fantasy characters, like Barbapapà in Vienna, Sonet Butterfly or Charles and Ply.

When you start to work, assembling two chairs, do you already have an idea in mind about the result? I saw a video on YouTube, the making of aradson, showing you and one of your staff, Harry, in the design phase. You’re losing the initial idea sketched on the table with a pencil, and then at a certain point you say: «I want to save it». What did that mean, in that precise moment?

It’s easy to find a type of chair on which to start working, but if I don’t manage to finish I get stuck, so I move on to something else, and then go back to the work later. I’m not so tied to the starting point, but when I’m working on a prototype I have to at least try to complete that initial idea. In the case you saw in the video, I wanted to save the first idea, but in the end the result was different from what I previously had in mind…

Your way of working gives new life to forgotten objects, and at the same time it sacrifices the lives of objects that have made history, furniture by Gio Ponti or Carlo Mollino. Is this an attempt at interaction or reinterpretation of those works, or is it a matter of irreverence with respect to certain great masters?

I think that to create something new you have to deconstruct what exists or forget the past. I believe it is hypocritical and wrong to imitate a master or to want to become a new Ponti. For me, it is important to “cut up” what already exists: I do it respectfully, I see it as a sort of process of knowledge. I don’t have to start with pure raw material. Even something that has already been worked or utilized, and has its own form, can be seen as raw material from which to make another object. It’s not a question of “too much respect”, but of the evolution of thought. Excessive respect can hold you back. In the first performance I did at Design Miami/Basel, in 2008, If Gio only knew, I used the furnishings of the Hotel Parco dei Principi in Sorrento, designed by Gio Ponti. I felt hesitant, hampered by a form of excessive reverence. At the tenth work I let myself go, gripped by the enthusiasm of changing the fate of those objects. I thought that actually there was not much of Ponti in those furnishings, they were produced in a series, industrial, for a hotel. I didn’t want to destroy Ponti because he’s Ponti. There was certainly an element of provocation, and it is no coincidence that I chose to do the performance at Basel, because at a fair that defines itself as a fair of contemporary design most of the stands were offering Gio Ponti and design from the 1950s and 1960s. I didn’t see any space for young designers…

Martino Gamper, Sonet Butterfly, 100 Chairs in 100 Days and its 100 Ways, 2005-2007. Photo: Åbäke, Martino Gamper.

Speaking of the design market, what do you think about Ron Arad and Marc Newson, two of today’s contemporary design stars? Are they still designers or are they artists?

I’m a bit perplexed, not so much about their identity as designers, as about the fact that we’re talking about design or the market. Ron Arad was my professor in London and Vienna, I admire him very much. One day in class he said: «I will make the first chair you cannot sit on». From that point on, for me it was no longer design. Ron wanted to shock the design world and the market. He wanted to choose for the market out of fear that the market would choose for him, reaching the point of almost controlling him.

You’ve never done industrial productions?

That question comes at the right time. I’m just about to do my first industrial production, though I can’t announce anything here. Maybe you’ll see something at the next Salone del Mobile. I am curious about working with industrial processes. The industry, in my view, has entered a cul de sac, because it has not opened up to new processes and it doesn’t have clear ideas. It often approaches a designer without knowing what to commission him to make, just fishing for proposals. The industry doesn’t have time to devote to the creative process, but without it there can be no room for new ideas.

Something you’d like to ask Mollino?

Why didn’t you ever teach?

A question for Gio Ponti?

If I had cut up Mollino’s chairs back in your day, would you have spontaneously given me your pieces?

Speaking of teaching, you have done it for five years at the Royal College in London. Why is teaching so important for a designer?

When you teach you are no longer the center of attention. You have to shed all your baggage, your convictions, to help students to understand what design is, guiding them in the direction of their talents. Students are very critical and you can learn from criticism. And to develop the ideas of others, you have to be very flexible.

The Trattoria al Cappello, a project for a nomadic, multidisciplinary restaurant, comes from your collaboration with the graphic designers Maki Suzuki, Kajsa Stahl and Alex Rich, all classmates from college. How did the idea come about, and how was it put into practice?

In London restaurants are too expensive, the quality is low, and we’ve always liked good food. We often organized dinners together with friends. That led to the idea of putting our work and our passion together, so we decided to organize a happening once a month in which we would design everything, from the menu to the furnishings, cooking for a limited number of guests. The guests were never only friends, we would also add some people we didn’t know. The first people to respond to an invitation sent out by e-mail would have a reservation.

Where did the name Trattoria al Cappello come from?

Hattonwall is the name of a street in London’s East End, and there was a bar there run by friends, the Hat (Cappello) on Wall, a semi-legal place with just a counter: that’s where we held the first ten dinners.

Do your dinners – veritable happenings – always have a magical combination of art, food and friendship?

Yes, for the guests. We always try to find the right combination, experimenting with new things, but something always eludes us. Sometimes the guests don’t make a good mix, often they are strangers, and they find themselves sitting at the same table…

You once said that the design process is like cooking. Could you tell me about the connection between ideas and chance?

In the kitchen you work with ingredients, and in design you start with materials. You constantly have to deal with chance, because you work with heat, you have to make quick decisions, there is no time to think. That also happens in my workshop. The dish doesn’t always come out perfect, but there is still something interesting that makes it worth tasting. I know the world of cooking, when I was a student I worked as a cook and a waiter, to make ends meet. In my family some of my uncles have businesses, like guesthouses and rural tourism facilities. My parents are farmers, so I know about the raw material of food. What I want, though, is not to get into the logic of a restaurant: I want to experiment, guided by curiosity. For me socializing has more value, I put the accent on that.

Trattoria al Cappello, London, 2009. Created by The Trattoria Team: Martino Gamper, Maki Suzuki and Kajsa Stahl. Photo: Amit Lennon

Your favorite dish?

Pasta with ginger, my recipe.

In 2004 I was involved in a workshop with Rirkrit Tiravanija entitled No Vitrines, No Museums, No Artists. Just A Lot of People, organized by Domus Academy. The performance of the trattoria reminds me a bit of the subtle spirit of his works. Rirkrit has created situations in which people spontaneously socialize, often around a hot stove. His work abandons individualism and opens up to the audience; the viewers are no longer spectators, but players. Could that also be a leitmotiv of your works?

Yes, involving people is a part of the heritage of mountain people. Culturally, I’m used to inviting. I am closely tied to the context in which a project begins, the client or the person it is for, and every element of the process. I want to pay attention to every step, in every object I create there is a piece of someone, not just because I use objects that have already been experienced, but also because they are born with an already shared destiny.

Is your work intentionally ecological? There’s a lot of talk about recycling, above all…

Yes, but I don’t like the term recycling, it has connotations of poor quality: after recycling material is never at its best, never retains its fullest potential. In English, there are the terms recycling and upcycling, another cycle, another life. The chair you find on the street, that no one wants, has no value, so giving it an idea and including it in one of my sculptures means revaluation. More than recycling, it would be better to talk about sustainability today. We need to think and create so that things will have a longer life. Ecological things, if they are based on pure recycling, last even less, so they reinforce the idea of a weak system of ongoing consumption. A chair should not cost 30 euros, it should cost much more and last a lifetime. It is true that everyone can afford to buy chairs nowadays, but in the end we’ve reached an absurd situation in which each of us could buy himself one chair a day. Instead, we should think about why food costs so much and chairs cost so little…

Your works are one-offs or limited editions, choices more common in the art world… why?

The reason why I have never done industrial productions is simple, and it is connected with my method: the fact that I use objects that already exist and manipulate them, in the workshop, prevents me from using the industrial process. The limited edition makes no sense, it only exists for the market. For example, the Together bookcase, which I made in an edition of 12 pieces for the Nilufar Gallery in Milan, is a system that could be reproduced, but it is composed of modules of different sizes, so all the pieces are different.

The commissions for some of your works come from colleagues and friends.

About 70% of my work happens spontaneously, without a client, or from a personal commission.

You have always worked on a small scale, with objects or interiors. What fascinates you about that dimension?

I’d say that choice is dictated by the fact that I have not had other opportunities. You can’t work on a large scale by yourself, or in the workshop.

Are you attracted by the idea of working on a larger scale? Of course that would mean losing much of the crafts approach…

Yes, I would like it, but I don’t have the expertise of an architect. I must say that if I could choose, I’d be more interested in doing a building than an urban plan.

You are always restlessly looking for new ideas, and you’re a dreamer: a stool can lead to a rocking chair, a football can lead to a lamp. Would you tell me something about your idea of craftsmanship? That’s a word that works best in English…

The aspect of craftsmanship helps me to express myself, if I was good at drawing I wouldn’t make sculptures. Why should I do something that looks industrial? The defects of my works are also their beauty, industry can’t do that. It’s my way of standing out. It is not a marketing strategy, but something very close to my way of thinking.

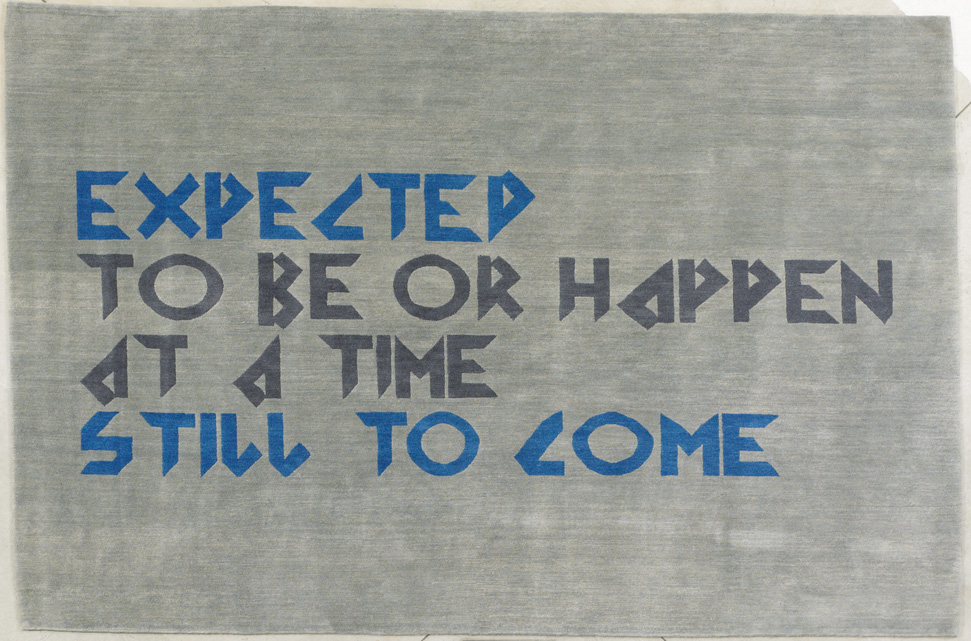

For the Nilufar Gallery you produced a carpet, Carpet Future, made by hand in Nepal, bearing the inscription Expected to be or happen at a time still to come. What does that phrase mean to you?

That was a piece commissioned by Design Miami/Basel in 2008, for the selection Designers of the Future, which presented four designers. It is my interpretation of the future: waiting for the moment that is still to come. The font I chose for the phrase is typical of Seventies science fiction, when the future was still a fantastic vision.

Martino Gamper, Carpet Future, 2008. Courtesy: Galleria Nilufar, Milano

What has changed, with respect to the vision of the future of thirty years ago?

Today we have a more disenchanted vision of the future. Time passes quickly, but our world does not change so quickly. In London we go on living in Victorian houses and we don’t imagine ourselves in spaceships. The appeal of science fiction has been replaced by the vintage trend. In short, the future will be slower than what we imagined thirty years ago. The only serious questions to consider are: how will we be able to live on this planet without any resources and with climate changes that have already had disastrous effects?

Tell me about the carpet as object.

Carpets interest me because they have been totally undervalued in contemporary design. I don’t only concentrate on the graphics, the floor as a design element is just as fundamental as a table or a chair. In the Orient the carpet is the most noble of all domestic objects, it was used to pass on stories; in the Occident, on the other hand, it has completely lost its narrative value, and become a purely decorative object.

What are your historical references in design and art?

Many and none. To name a few names: Franco Albini, Dino Gavina, Carlo Mollino, Gio Ponti, Ettore Sottsass, but also Mathieu Mategot, Charlotte Perriand, Jean Prouvé. Some of my teachers, like Ron Arad and Enzo Mari. And, among the artists, Michelangelo Pistoletto, Gianni Colombo and Martin Kippenberger. I am free, I don’t look at them.

You’re obsessed by corners. It is an obsession found in many of your projects: from the public ones, like Berlino Bench (2004) and The Book Corner (2002) for the British Council, to others like Sit Together Bench (2000), Totem Shelf 01 (2000), Booksnake Shelf (2002), the various Corner Lights (2000-2003), all the way to the Kid’s Corner (2002). What does this element represent for you? Is it a challenge or an old traveling companion?

Definitely an old traveling companion. My college thesis was on the corner as a design element. The corner has to do with the inside of a space. Architects don’t pay much attention to it, and designers fear it. All rooms have unresolved corners, so I like to think of the corner as the place where furniture and architecture meet. Then there is also a social side: beyond their geometry, corners are places that make you feel safe, solitary places where you can seek refuge and think. At the same time, they can be claustrophobic, isolated… just think about certain expressions, “go stand in the corner”, “the safest corner of the house”, “he’s in my corner”. The corner is contradictory, but it has great potential.

Can you tell me about an idea you’ve never been able to put into practice? A scoop, a dream to tell, an appeal…

A suitcase. I can’t find a suitcase I like, one that is functional. I would like to invent one.

The most important project, for you?

100 Chairs in 100 Days and its 100 Ways.

The project you regret, if there is one?

Lots of little things I wouldn’t have wished to do, but I don’t even remember them.

An opportunity lost, an opportunity snapped up?

All kinds of lost ones… snapped up: to make an industrial chair.

Martino Gamper, Cover Version’s, 2009. Photo: Anna Arca

Besides you, is there someone to whom you own much of your success?

Many people: my friends, above all, the Åbäke studio, my wife, the Nilufar Gallery, my family, my teachers.

Maybe when you were a child you liked Lego… how have you transported childhood or the past into your work?

Life in the mountains is different from life in the city: even had I wanted them, there were no video games. I spent my time helping the others, cooking, doing chores. I really liked helping people.

You recently got married… do you think this new life will change you?

It already has… in a positive way, of course, I live a different life. I work a bit less and that’s good for my activity too. I would like to be less egotistical. My wife and I work together: she is an artist, we met because she wanted to involve me in one of her projects, that’s how the story began. She helps me and I help her.

What is lacking in today’s design?

Design today lacks reflection on the object as something that lasts in time, and ages well. Enzo Mari has always said this. Unfortunately, because we are all fashion and trend victims, to some extent, design is done by thinking about a very short life cycle for the work. We too are afraid of aging badly, and I’d say

we are also afraid of the passage of time.

In your view, was it easier to get known in the past?

The world of the media is fast, it offers you many more possibilities than before, but it forgets you just as quickly. Everyone is in a hurry to become rich and famous. I believe this attitude generates a flawed approach to life. I think it is more interestingto develop your thinking, without the tiresome pursuit of fame. In the end, time will be the judge…

Martino Gamper, Omback, 100 Chairs in 100 Days and its 100 Ways, 2005-2007. Photo: Åbäke, Martino Gamper

Martino Gamper, Robot Chair, 2008. Courtesy: Galleria Nilufar, Milano

Trattoria al Cappello, London, 2009. Created by The Trattoria Team: Martino Gamper, Maki Suzuki and Kajsa Stahl. Photo: Amit Lennon

Martino Gamper. Photo by Maria Ziegelböck.