5 September 2016

Michael Cunningham was born in 1952 in Cincinnati, Ohio. As a child he was always on the move, following in the footsteps of his father Don, who worked in the advertising sector. The family settled down in Pasadena, California, when Michael was ten. Here his mother Dorothy found herself living too restricted a life for a woman of her intelligence: Laura Brown, the depressed housewife in The Hours, is based on her. “If as a child you see your parents unhappy, you suspect this has something to do with you,” Cunningham said a few months ago in an interview published in La Repubblica. “But let’s look at it like this: if you’re able to accumulate enough guilty feelings when you’re young, you’ll have something to write about for the rest of your life.” His interest in literature was kindled during his adolescence, when the coolest girl in the school, with wild hair and long fingernails, persuaded him to read T.S. Eliot and Virginia Woolf, while in class they analyzed Bob Dylan’s lyrics. Michael read The Waste Land, but the book that made the greatest impression on him was Mrs. Dalloway: he was a 14-year-old Californian who dreamed of becoming a painter and, however curious it may seem, the mystery of art represented by that wealthy 52-year-old member of English high society became very much part of his life and never left him. He finished high school, put aside canvases and brushes and enrolled in the courses of English Literature at Stanford University. After graduation, he was admitted to the Writers’ Workshop of Iowa University and started to publish his first stories in magazines like The Atlantic Monthly and The Paris Review. He got his first positive reviews with the novel A Home at the End of the World: a few months earlier he had sent a chapter of the book to The New Yorker, convinced that it would be rejected because of its lack of commercial potential. And yet the magazine published it, creating a buzz around his name. This was followed by the marvelous Flesh and Blood, but it was The Hours that made him one of the most widely read contemporary American authors in the world. “By now my full name is the Pulitzer prizewinning author of The Hours Michael Cunningham,” he jokes. “There is no occasion on which I’m not introduced in this way.” Today he lives in New York. After seven novels and a short book devoted to his love of Provincetown, a town on the Atlantic coast 300 miles from New York, he has published his first collection of short stories A Wild Swan, brought out in Italy by La Nave di Teseo under the title Un cigno selvatico. Their characters are the heroes of the fairytales we remember from our childhood: Cunningham tells us about their future, as if now we have grown up the classic ending “and they lived happily ever after” were no longer enough.

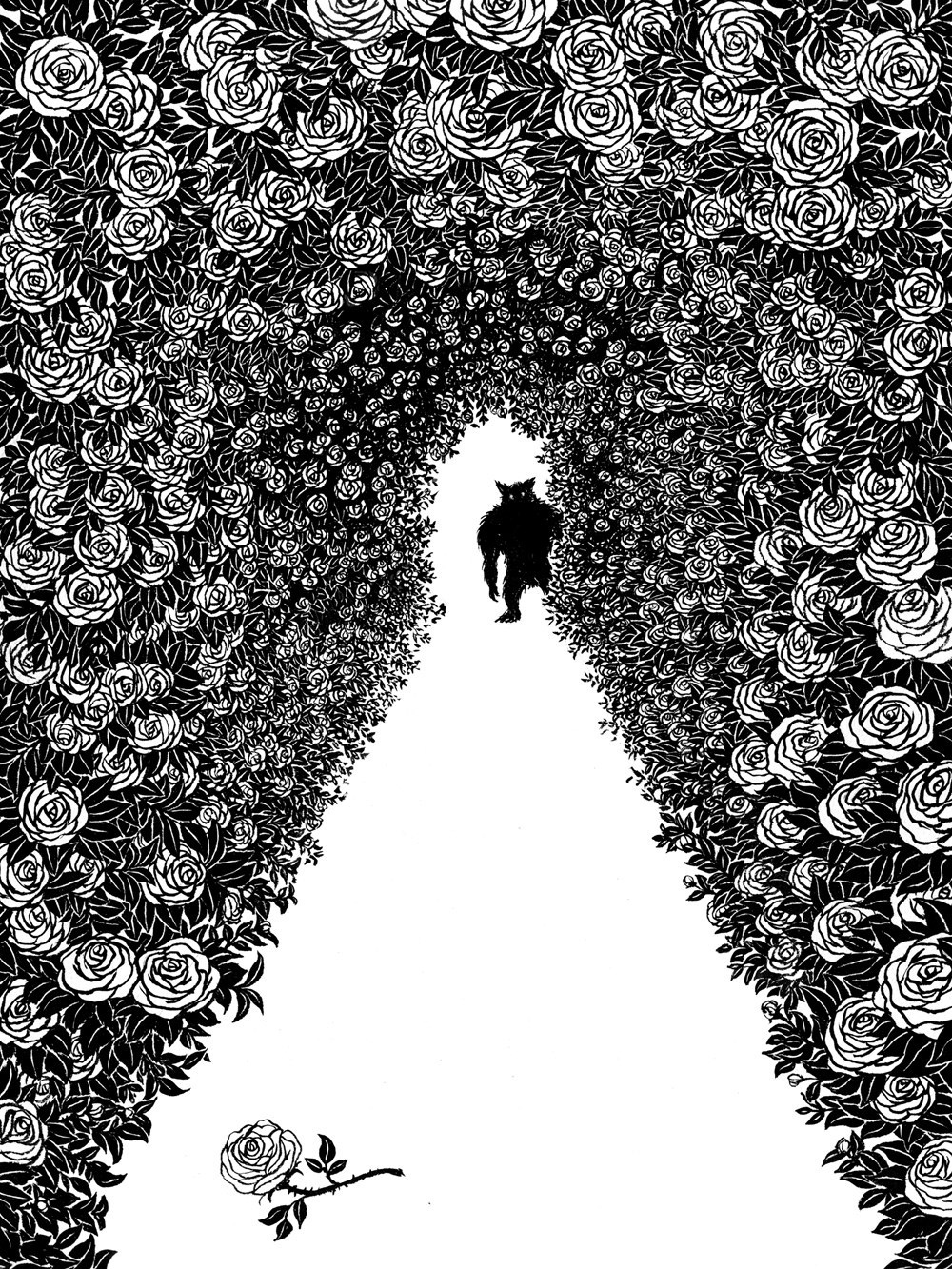

Beast. © 2015 Yuko Shimizu.

“Happily ever after is more than enough,” declares the writer, “it just doesn’t seem like a realistic view of anybody’s future. Sometimes one is happy, or at least hopes to be. At others one is unhappy. That’s life.”

Sigmund Freud said that if we were constantly happy, we wouldn’t recognize it as happiness at all, it would simply be our ongoing condition, it wouldn’t feel extraordinary.

I agree with old Sigmund about that. I do believe in happiness but I believe more entirely in a life that encompasses the full range of emotions.

Short stories are perfect for our frantic era. Why did it take you so long to publish your first collection?

I don’t really write short stories, though I read them all the time. I don’t think, narratively, in the short bursts required by short stories. I need more time and space for the characters and their stories to develop, I don’t do well with the economy a short story demands. It’s simply how my brain is wired. The fairytales, of course, had to be short. But I’m 100 pages into a new novel now, and don’t expect to write any more short stories in the near future (though of course, one never knows).

A Wild Swan and Other Tales is illustrated by Yuko Shimizu. What do you think her illustrations add to your words?

I love Yuko’s drawings. When she agreed to illustrate the book and asked me what I had in mind, I told her I wanted her to have complete freedom; to choose the images that most struck her, and draw whatever she wanted to draw. The result, to me, is simultaneously an illustrated book of fairytales and two books combined—one made up of the stories themselves, and a second one made up of Yuko’s ravishing artwork.

A Wild Swan. © 2015 Yuko Shimizu.

Why did interrupt your dream of becoming a painter?

I didn’t feel like I had a real gift for painting, as much as I wanted to paint. I started writing, and wasn’t sure if I had a gift for that, either, but found that my interest in writing—that is, in the challenge posed by creating life using only ink, paper and the words in the dictionary—was fascinating to me in ways painting had never been. I don’t feel like a good writer every single day, but I never lose my fascination with the process of writing. I’m obsessive, I’ll write the same sentence ten or twenty times over, until it feels right. I’m not sure one can be a writer, or an artist of any kind, without that obsessive quality.

What are your favorite contemporary art galleries in NYC?

There are so many. But of all the New York galleries I love, I find that Paula Cooper—who’s been showing art for decades—consistently shows work I find moving and remarkable.

What contemporary artists do you like the most?

Again, too many to name, but the ones who come most immediately to mind are (in alphabetical order: a few of them are no longer alive, but I think of them as contemporary): Carl Andre, Felix Gonzales-Torres, Anish Kapoor, Gerhard Richter, Robert Ryman and Rachel Whiteread.

Is New York still the city famous for welcoming people who have a dream to make come true?

It seems sometimes like the entire population has come to New York in pursuit of some dream or other—if you weren’t pursuing a dream, why would you put up with the difficulties of New York? That’s not to say that all those dreams come true, far from it, but I do love living in a city so densely populated by dreamers.

Poisoned. © 2015 Yuko Shimizu.

Where do you keep your Pulitzer Prize gold medal?

On an unobtrusive shelf. I don’t want anyone to come to my apartment and be confronted with the prize, that would seem so pretentious.

Who are the young American writers we should read?

There are so many. Among them: Teju Cole, Garth Greenwell, Adam Johnson, Tea Obreht, Karen Russell, Sarah Shun-Lien Bynum and Hanya Yanagihara, just to name a few.

Have you ever been afraid that reading other authors’ novels might influence your own writing?

Not at all. I hope to be influenced by other writers. I mean, I’m not going to turn into William Faulkner or Gabriel Garcia Marquez by reading them. I’ll just take in a molecule or two of their genius, which is the kind of influence I want.

What’s the last film you enjoyed watching?

The last movie I really loved was Mad Max: Fury Road.

Do you have a favourite movie theater in Manhattan?

The Film Forum. Close second: Sunshine Cinema.

Ever After. © 2015 Yuko Shimizu.

When did you first move to New York?

About 25 years ago.

You travel a lot. Is there a country where you feel that freedom of expression is at its greatest?

I love Berlin, it’s so alive right now. And London. But really, I feel most free right here in New York.

I read that you lived in a Greek cave overlooking the Egean, years ago. Is that true?

It is. I was in my mid-twenties, had saved up a little money and went with my then boyfriend to live in Greece (which was incredibly inexpensive then), because if not then, when would I? We lived in a cave overlooking the Aegean. It was amazing. We stayed until our money ran out, which was almost an entire year. It was important to me to spend some time outside the US. It’s still important to me, but especially so when I was young, when I’d never lived anywhere but America. It was great to be shown so forcefully how other people in other countries live—the ways in which we were similar, the ways in which we were different. It was a significant aspect of my education.

Y. © 2015 Yuko Shimizu.

N. © 2015 Yuko Shimizu.

© 2015 Yuko Shimizu.