29 January 2013

In response to great demand, we have decided to publish on our site the long and extraordinary interviews that appeared in the print magazine from 2009 to 2011. Forty gripping conversations with the protagonists of contemporary art, design and architecture. Once a week, an appointment not to be missed. A real treat. Today it’s Maurizio Cattelan’s turn.

Klat #02, spring 2010.

Sunday 28 June 2009. A few days after starting this interview, which then continued as an intermittent conversation, I get a press release from the address of Maurizio Cattelan announcing an opening, that same day, in New York, of an improbable posthumous retrospective entitled Maurizio Cattelan is Dead: Life and Work, 1960-2009. Without too much thought, I respond with spontaneous cynicism, typing AMEN in capital letters. But how am I going to interview a corpse, now? Then I start to think about the tragic destiny that deprived us, in just three days – with the due distinctions of proportion – of two pop cultural icons of the 20th century. After Jackson, Cattelan. How will the world survive? The most disturbing coincidence is the fact that a few days earlier, during our first chat, among his staccato, faltering phrases, as if he were always trying to avoid expressions that might sound the least bit presumptuous and ruin his low-profile image, Cattelan said: «We’re just walking dust». We laughed over that macabre turn of phrase. A reaction similar to the one often caused by Maurizio’s works: they make you smile or chuckle, like a sharp witticism, but then you realize they’ve left you with a strange sense of melancholy. My mother, as far as she knows it, likes Cattelan’s work, especially his infantile alter-ego that rides around on a remote-controlled tricycle (Charlie, 2003), because – as she puts it with (a)critical conciseness – «it makes me laugh, but then I get a lump in my throat».

Maurizio Cattelan, 2010. Photo: Pierpaolo Ferrari

Now that I’ve gotten over my gloomy musings on your untimely demise and ascertained, to my relief, that you are alive and kicking, I’d like to share a startled realization with you: I just noticed that you are 50 years old: 1960-2009! Obviously I knew you were born in 1960, but reading the two dates like that, in a pair, makes your half century of life seem like a considerable slice of time and experience.

I’ve been doing this job now for twenty years, and when I think about it I’m amazed, because I was never able to hold a job very long in the past. Art saved me. Not in the sense of giving me wellbeing and security, but precisely in the sense of saving me from the street. Otherwise I’d have ended up in prison. Or dead.

What you say is interesting: in “normal” society you were an outcast, a loser, but in the art world you have become an absolute protagonist. This proves that the two spheres are governed by different dynamics, different rules…

I was lucky (laughs, ed). Actually, in the art world you make your own rules. I did it and I followed them. It would be extremely presumptuous to say that what we do has an impact on the lives of people, on society. But art saves those who make it.

This idea of art as salvation, if not for society at least for the artist, is fascinating. I’d like to pursue this subject. First, though, let’s trace back through your origins as an outsider, before your artistic redemption. Recently I saw a TV program on terrorism in Padua at the end of the 1970s, and the things jibe: maybe that was the fate you were talking about, the thing that would have made you end up behind bars or six feet under, the fate you escaped thanks to art?

In the battle for independence I left home early, at the age of 18. But I had already decided to leave when I was 14. It was 1978, I wasn’t so far from certain circles, but I had my own plans: changing the world seemed boundless. First I had to try to change my own situation. And I couldn’t take chances: if I blew it I’d have to go back home. That would have been an enormous defeat for me. My struggle for independence meant gaining autonomy, getting free of the family discussions about every decision. I clearly recall the day of my 18th birthday: I had two plastic bags. My mother asked: «Where are you going?». And I said: «Away from home». «But away from home where?». «It doesn’t matter to you. I’m just leaving. Ciao». «Oh, c’mon, don’t be silly, no one leaves home with plastic bags». But I only had my underwear and socks to take with me…

Maurizio Cattelan, Untitled, 2007. Courtesy: Maurizio Cattelan Archive

And you never went back?

No. At first my mother took it very badly, like a rejection. My father, on the other hand, took it in his stride. One less mouth to feed!

Once you had left home what happened?

I continued my education. But I couldn’t do it during the day, I had to work to support myself. For three years I worked eight hours a day and went to night school. My first job was as an apprentice bookkeeper. Then I cleaned stairs. But there was a logic to this path: I had understood that working eight hours a day was a waste of time. My objective was to reach zero hours per week, in other words not to work but to have income anyway. First, though, I had to detox, not so much from work as from the (limited) education I had received. I came from a traditional Catholic working-class family, that tells you: «if you don’t work you don’t eat». There was a punitive atmosphere at home. Since I was 12, I spent every summer working. I stayed in Padua until I decided to dump all jobs. It took me seven years to get free of work and the last six months were on sick leave. I worked at the morgue. I resigned in 1984 and spent another year in Padua, then I moved to an even smaller place, Forlì, where I stayed for five years.

Why Forlì?

Women… it was interesting there, because I found myself with the whole day free. I didn’t work. It was survival.

How?

You manage. A bit of this, a bit of that. With near-zero expenses you don’t need much. I lived on things I had saved and invested for income. When I worked I had also done it with the idea that at a certain point I would stop, so I had to be able to support myself. I had all the time I wanted, and that’s a privilege you cannot buy.

Would you go back to those days?

I’d go back to the days in Forlì: they were wonderful, for the dimension of continuous discovery. I wouldn’t go back to Padua, though!

When did you move from Forlì to Milan?

Actually I was already going back and forth. I’d go to Milan to sell the things I had started making, though I didn’t know what they were. I told myself: whatever you decide to make has to sell. Even when I began to work with galleries, I decided that if it didn’t lead to wellbeing in the course of three years I would change my plans. My nightmare was to end up making a bad replica of my family. And I couldn’t afford to find myself in a situation in which I was completely broke and had to ask someone for help. I had no safety net. I had stopped seeing my friends from Padua, and those from Forlì as well. Usually, when I moved to another city, or another scene, I also changed my set of acquaintances.

Maurizio Cattelan, Untitled, 2008. Photo: Zeno Zotti. Courtesy: Maurizio Cattelan Archive

What were the “things” you didn’t know how to define, at the time?

Functional objects, one-offs. I would make one every so often, just to get by. I had taken the yellow pages and copied the addresses of all the specialized magazines, then I went to all their offices with the photographs of those things and… I was pretty lucky. It’s true, I went to all of them, but they all published my stuff. All of them. But at a certain point, when they asked me to do something more substantial, I realized I wasn’t interested. My head was elsewhere.

Where? In art?

Yes, it was always there. I went to see exhibitions. Actually there was one year, maybe a year and a half, when I worked with Dilmos, and in parallel I had made a sort of catalogue – here the credit goes to the girl I was seeing at the time – showing the things that got produced in the workshop at Forlì; it wasn’t clear what those things were, so they could be functional objects, but also drawings and photographs. A bit of everything. I don’t know why, but already, back then, I wanted to go to New York, so I sent a thousand of these catalogues to all kinds of galleries in New York. Since I still had a dozen or so, I said to myself: what the hell, let’s send a few in Italy too. I got only four replies for a thousand catalogues sent, and one of them asked me to participate in a group show, in 1989. It was Galleria Neon in Bologna. Then they offered me a solo show, of my objects again, but I no longer liked them: I wanted to do something else, though I still didn’t know what, so I was confused and I put up a sign outside the gallery with the message “be right back” (Untitled, 1989). Both the objects and the works I made over the next four to five years developed in a way that was not very orthodox. I learned by doing and by watching what the others were doing. I had no idea what an artist was, no idea about how galleries work.

So where did this attraction come from, for a scene you didn’t even know about? Why were you so determined to become a part of it? It certainly wasn’t a matter of family background…

…nor did it come from friends. I don’t know. I have no idea.

I did know a group of artists in Forlì: what they did was very academic, so they were not a model for me and I was not a threat to them, given the fact that I didn’t know how to do anything. Their life was not so different from mine, but they had style, there was something that attracted me, like with a woman: you can’t say she attracts you for her nose or her mouth, it’s the whole. It was something that excited me.

So you took a shot at it. But when did you understand that you had really made it?

I don’t know what “made it” means. Let’s say that the Pope (La nona ora, 1999) was the turning point, when I finally felt like part of the system. Before that I said to myself: until they notice, keep it up (laughs, ed).

Maurizio Cattelan, La Nona Ora, 1999. Photo: Attilio Maranzano. Courtesy: Maurizio Cattelan Archive

You were very determined…

I had no choice. But I did press forward in an empirical way.

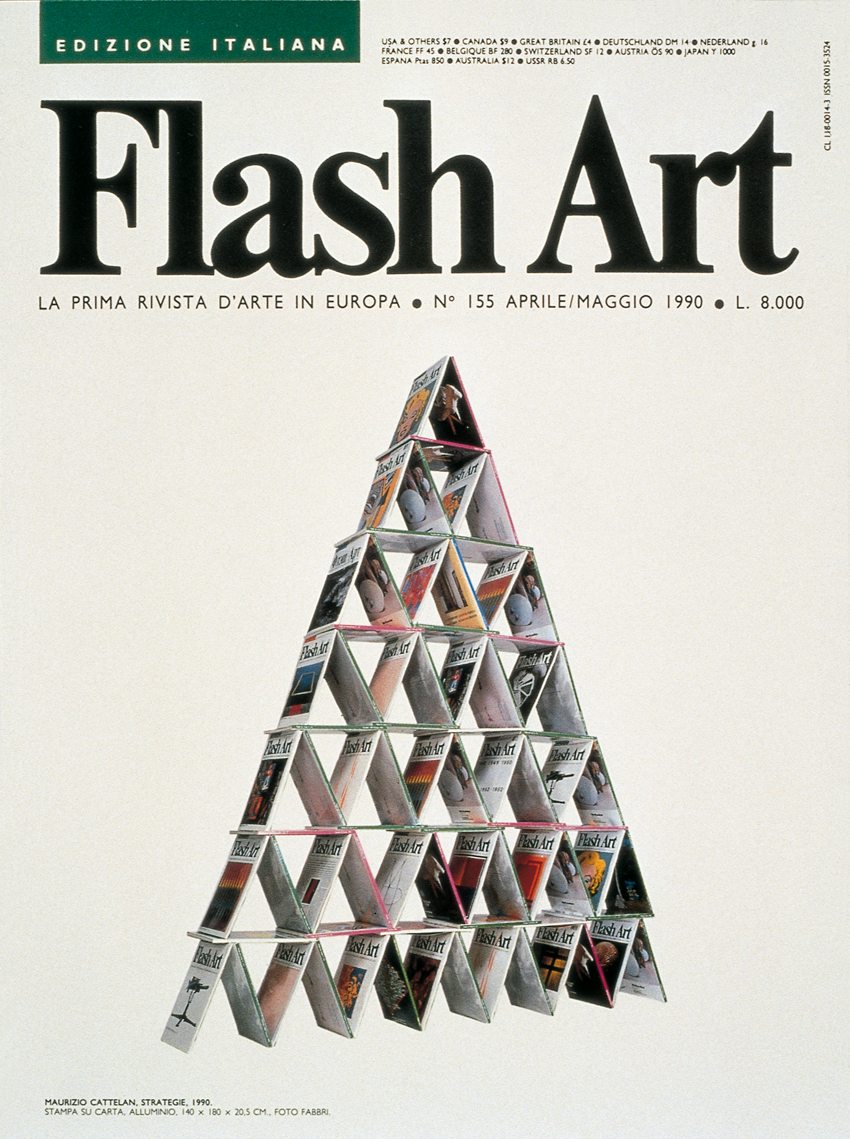

You’re telling me you didn’t have a strategy? But you even grabbed your own cover of Flash Art…

I thought about the rules of the system and it was clear that they would not put me on the cover, so I thought I might as well do it myself. It was a self-legitimizing action. I went to the printer who works for Giancarlo (Politi). I bought a thousand copies that still hadn’t been bound… I don’t remember, maybe I bought them from the editorial staff. Anyway, in Ravenna I had my cover printed (Strategie, 1990). I presented the magazines in three galleries, because they had to be seen in multiple places: Studio Oggetto in Milan, Studio Leonardi in Genoa and Neon in Bologna. I don’t remember where I bought the advertising, but it was a project with a precise structure.

And Politi?

I don’t think he even noticed. The thing didn’t get much attention. But right after the cover I did the immigrant soccer team (AC fornitore sud, 1991). I thought about what is the most popular thing in Italy and I used soccer to convey, through a very simple principle, the emerging phenomenon of immigration from outside the EC. I had them play matches where I was the coach and the president of the team. The idea of making a table soccer game (Stadium, 1991), where my team of immigrants could challenge a team of Italians, came after the invitation to participate in the group show Anni 90 at the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Bologna. Speaking of that show, I clearly recall being at an opening in a gallery in Brera (I went to see how things were done) and there were all the hot artists of that moment. They were all talking about that show in Bologna. Listening to a conversation, I heard one of them say: «I’m not doing it, they invited too many artists». And I thought: you don’t go, I will, and I’ll show you. In the end, someone’s always ready to eat somebody else’s leftovers, and to gain by doing so…

So you started by scavenging the “leftovers” of others, and you became a star! As you were saying at the start of our conversation, you’ve been doing this job for 20 years now. What happens today?

With the outbreak of the crisis, about a year and a half ago, suddenly, from one day to the next, our way of seeing things changed radically. Luckily these changes happen, that let you see how things really are. The artists who were idolized until yesterday have disappeared today. The wheel turns. Now the challenge for us, for the artists of my generation, is to survive. Things can never go back to being the way they were before. You can be the world’s greatest artist, but this cyclicality is unavoidable. For me, personally, it is a very interesting moment of reflection. Now I can do more shows with the same works, but with different atmospheres, depending on how I handle them. The shows in progress (at the Menil Collection in Houston) and future shows (at the Guggenheim in 2011 and at Versailles) allow me to take stock of what I’ve done. I would never have imagined that an exhibition could put you in the position of analyzing what you’ve done, of seeing dominant lines in your production. Not that you can manage to understand why you did certain things and not others, but you can identify some obsessions. And you can understand what caused you to make the weaker works. My mistakes are undoubtedly the result of the fact that I don’t have a studio, so the moment of testing is the exhibition itself: it is there that you understand if the work functions or not. So this realization that a mistake has been made, or that good results have been achieved, is never a private matter. The thing that surprised me, in this reflection on my work is that somehow, if you’ve haven’t totally “dropped your trousers”, integrity pays off. In the sense that no matter what happens, if it all goes to hell, you can still hold your head high. No one can take that away from you (laughs, ed.). Not that I’m all of a piece, there have been moments in which I’ve done things that, looking back, make you throw up your hands in despair, works done because someone showed up and said the groundwork was missing, that I ought to think about works of a certain kind, because those foundations are important. Doing them in a calculated way, you put things into circulation that may also constitute a nice “ornamental show”, but then they get separated, they show their frailty and you’re no longer there to defend them, to do your little promo campaign. And then the authority of the space is gone: the works find their way into someone’s home or some foundation, and have to stand up in dialogue with other works. In short, some pieces become boomerangs.

Maurizio Cattelan, Stadium, 1991. Courtesy: Maurizio Cattelan Archive

Are you very aware of the fate of your works?

I’ve learned. Now I may also destroy things.

You’ll never tell me which works you were talking about when you said «they make you throw up your hands in despair», will you?

I don’t need to, they are there for all to see. Now the challenge is to see if my works, even the “mistakes”, can have a life all together. At the Guggenheim retrospective all the works will be installed in a new format. It’s a big test, in visual terms. Then there are the technical-organizational problems, but it’s an opportunity to demonstrate that my works, good or bad, can have an ensemble dimension, in spite of what people say, namely that they are just “one liners”, wisecracks…

Do you feel as if you still have to prove something to someone?

I hate to admit it, because I’m not a great salesman for my things, but there are those who call my work scandalous, superficial like a wisecrack, clever. The usual three or four things people say about my work. Maybe they’re right, but I look at a lot of images every day, and I realize that an image without content deteriorates very fast and is destined to vanish – you don’t need to be an expert to understand this. While some of my works, after ten years, fifteen years, are still there, we’re still looking at them (me too) and saying: damn! About a dozen of my works will have no problem continuing to circulate for another five or ten years. I think the perception of my work has at times been overly influenced by media sensationalism, making the audience interpret it in a superficial way.

You were talking about integrity. What does it mean to you?

It is a very personal thing. As I was saying, in the art world you make your own rules and you are the one who has to obey them. I’ve done that, and I think I could have “dropped my trousers” a lot more than I did. The temptation of money and of the privileges it can grant is very, very strong. And then you may find yourself producing things just to sell them. If that choice is consistent with your work it’s OK, as I said before, but if the economic aspect becomes overwhelming and weakens your work then it’s a shame. From this viewpoint I can’t say I’m completely unscathed, but I’ve managed to defend myself.

For whom do you really make your works?

For myself, above all, and for two or three other people I have in my mind. If I can satisfy those people I have in my mind, then I’ll satisfy all the others – including the audience – because their level is very high…

They are your points of reference?

No, it’s something else… Let’s take an example: you’re a child, at school, you write a very good paper and get the best mark, you go home and you’re happy. Why?

Because I can tell Mom and Dad?

Voilà. Doing better than your best, to be able to say it, even ideally, to those who represent a reference model. That’s what keeps people going.

Doing better than your best to make them happy or to prove something to them?

That depends.

Maurizio Cattelan, All, 2008. Photo: Markus Tretter. Courtesy: Maurizio Cattelan Archive

So could it happen that the production of an artist, at a certain point, loses its intensity precisely because those people have ideally been satisfied?

It’s possible. Or it can also happen because the artist has resolved his problems. Where I’m concerned, work can be therapy. The therapeutic effect isn’t always there. But if you’re lucky you can find yourself faced with moments of revelation. Things come to the surface that have happened, that you repressed, tragic moments, obviously. I am always grateful when it happens. Now, looking at my works all together, I see that death is a vivid presence, and there is also the recurring theme of childhood. And there is certainly a lot of repression. When they say that the sins of the fathers shall be visited upon the sons it is true, in a way. Very true, in fact. In this case art is a therapy that, when it works, lets you understand what made you become who you are. If you’re good, you use it not to change yourself, but to understand yourself. So the work can permit me to understand myself, and that is already a major victory. All the other aspects, like economic rewards or public acclaim, are important, but in any case they are temporary. In the end, if you stay lucid, and try to understand why you are doing this job, you don’t do it for those reasons. The more material things you possess, the more time and concentration you have to devote to them. They won’t get you away from your obsessions, because the obsessions remain.

Is that why you seem to have a rather spartan lifestyle?

I’m a monk with many sins (laughs, ed). It’s funny: between the house I have now, the house I had twenty years ago an the house where I lived with my parents, nothing has changed. Only the address. I’m still here with a mattress on the floor. Now I have a spacious home in New York, but I still work in a corner by the mattress, facing a window. The other day I was thinking: here it’s the same, I still work in 16 square meters. The privilege is that maybe instead of being on the ground floor you’re on the tenth. I’ve been a prisoner for years, for good conduct.

Have you ever been psychoanalyzed?

No… I make a work every week!

Maurizio Cattelan, Untitled, 2007. Photo: Axel Schneider. Courtesy: Maurizio Cattelan Archive

Are you religious?

I grew up in a very religious environment. I was an altar boy and I spent a lot of time at the parish center and in church, because it was the way to be free. Am I religious? If I were not a believer, in some way, certain works I’ve done would not exist. I still haven’t come to grips with sickness and suffering, so I haven’t thought about it very clearly… But there’s a part of me, the good part (laughs, ed) that feels something…

Fifty years old. A time for taking stock. Haven’t you ever thought that to more effectively exorcise your obsessions, instead of producing Charlie you could reproduce a flesh-and-blood child?

Every work is a way of defeating death. You know, there are three ways to ensure yourself continuity: reproduce, make a will that covers donating your organs, or make works that, if you’re good, will last.

Maurizio Cattelan, Untitled, 2009. Photo: Zeno Zotti. Courtesy: Maurizio Cattelan Archive

Maurizio Cattelan, Untitled, 2009. Photo: Zeno Zotti. Courtesy: Maurizio Cattelan Archive

Maurizio Cattelan, Untitled, 1989. Courtesy: Maurizio Cattelan Archive

Maurizio Cattelan, Strategie, 1990. Copertina Flash Art. Courtesy: Maurizio Cattelan Archive

Maurizio Cattelan, Untitled, 2009 Photo: Nick Ash. Courtesy: Maurizio Cattelan Archive

Maurizio Cattelan, Ave Maria, 2007. Photo Axel Schneider. Courtesy: Maurizio Cattelan Archive