29 October 2012

Unidisplay, the latest installation of the German artist Carsten Nicolai, is an attempt to produce a universal language––a worldwide alphabet of images and sounds––and is on display for the first time in Europe at the Hangar Bicocca in Milan. Resident in Chemnitz and Berlin, Nicolai is a “veteran” of the art world: winner of the Zurich Prize in 2007, he has taken part in Documenta X, at Kassel, and two Venice Biennali. A celebrated composer and producer of music under the pseudonym of Alva Noto, he turns his art into a meditation on noise and sound, on language and image. A research aimed at revealing the meaning of the most primordial of human experiences: the way we perceive the world.

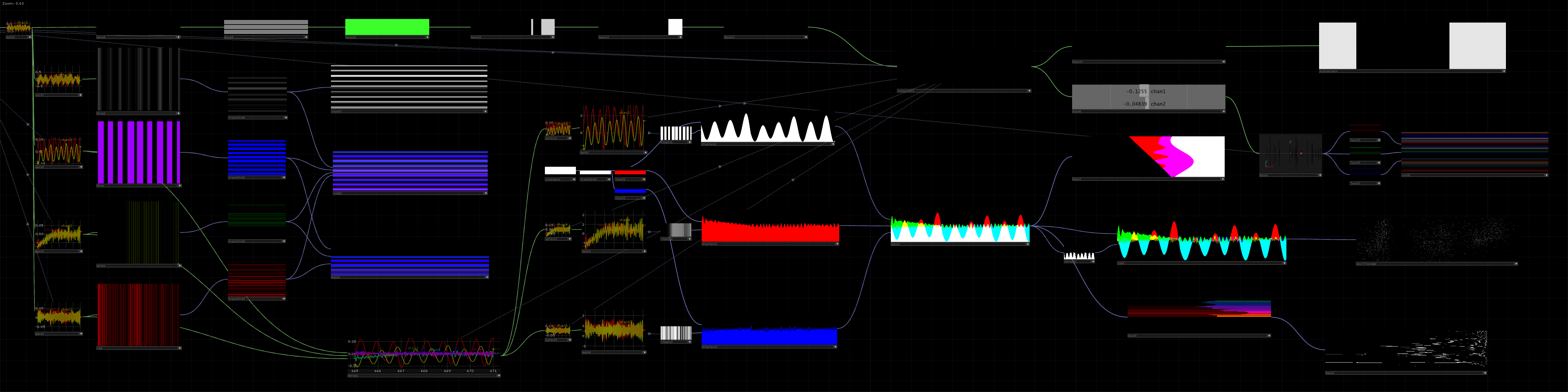

Let’s start with your most recent work: Unidisplay, on show at the Hangar Bicocca in Milan. The installation consists of a screen about 50 meters long over which move abstract images of a minimalist aesthetic that expand ad infinitum through the mirror walls at each end. The visual component is strongly correlated with the aural one, in a close dialogue between graphic forms, sounds and noises. The viewer sits in front of the screen, on a bench that vibrates with continuous impulses of sound. The title of the work is a combination of two words: “universal” and “display.” What are you trying to convey through this linguistic juxtaposition?

The term “universal”––universell in German––indicates a sort of container capable of holding several elements within it, each of which can constitute an installation in its own right. So “universal display” is tantamount to a simultaneous representation of more than one unit. In the specific instance, Unidisplay can be read according to three different parameters. The first is the one related to perception: the installation sets out to investigate the way in which our brain processes and perceives reality. The second is the semiotic aspect: the work reveals the existence of an alternative and universal language, based on images and free from letters or numbers. Finally, the parameter related to time: the work functions like a great visual clock, in which the various cycles of time are represented graphically.

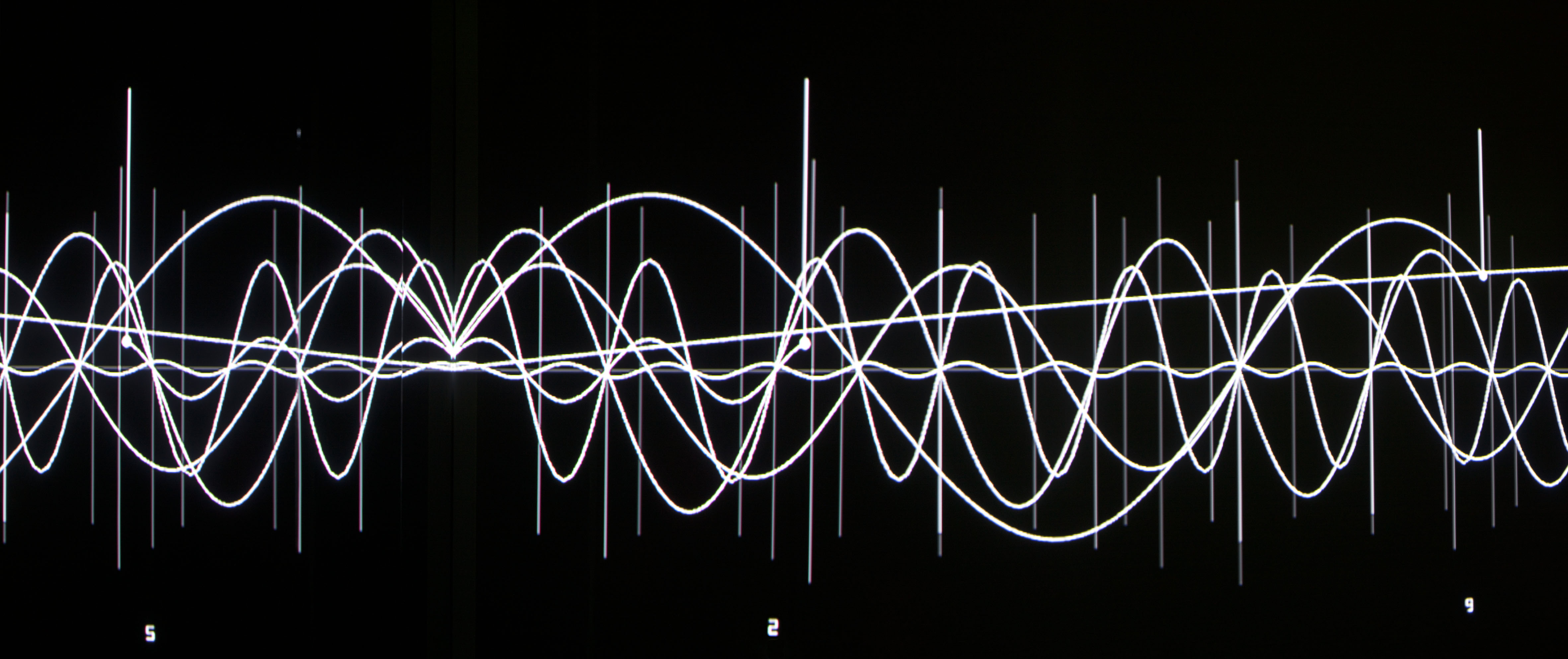

Carsten Nicolai, Unidisplay, 2012. Photo: Agostino Osio

Carsten Nicolai, Unidisplay, 2012. Photo: Agostino Osio

What relationship is there between Unidisplay and your previous works? I am referring in particular to the Uniscope series.

Uniscope is the title of a set of works that accompany my musical performances. They are “visualizers” of sounds in real time. Unidisplay is the “visual” companion of Uniscope, given that the driving force of the former is no longer sound, but the image. In Unidisplay the aspect of sound is no more than a gentle support for the succession of forms, it is no longer necessary.

So it is possible to speak of a shift in your artistic practice: from the attempt to turn music into image––born out of the desire to make sound visible––to the attention paid to the image in itself and the modes of visual perception. Perception that, in Unidisplay, is constantly disturbed by the use of particular visual effects like optical illusion, flickering and the complementarity of colors.

In reality I don’t think you can speak of a true shift, as both the approaches that you describe have always been there in my work––but perhaps were not visible in such an obvious way. I have always tried to make a conceptual distinction between my live performances and my installations: the performance has a limited duration, and thus a beginning and an end, during which I want to express the physicality of the sound. When I create my installations, on the contrary, I’m interested in extending the duration: first of all there is no need for me to be present, and in the second place anyone can decide to come and appreciate the work at any moment. In addition, in an installation I am seeking to generate in the viewer an experience of constant intensity, not at all “dramatic” or discontinuous as in the performance. My installations can be compared to plateaus, not to mountains that go precipitously up and down.

Carsten Nicolai, Moiré S7, 2010. Courtesy: Galerie EIGEN + ART Leipzig/Berlin and The Pace Gallery. Photo: Uwe Walter, Berlin.

You were born in Chemnitz, known as Karl-Marx-Stadt in the time of the DDR, a city with a strong tradition of textile manufacture. Do you think that this has influenced you in any way?

Totally. I grew up surrounded by cloth mills and industrial machinery: Chemnitz looked more or less like Detroit. In addition, there were schools of textile design and I lived in the midst of people who had machines for engraving. After the Wall came down, these factories closed their doors: this gave me a chance to explore them. I discovered splendid collections of designs made for looms and specific devices. The patterns of these drawings have had a strong influence on the way I try to visualize sound. Works like the Moiré Drawings (2010) take their inspiration from just these fabrics.

Let’s move on to your method of working. You make constant use of sophisticated technological equipment and your practice brings together different disciplines, including physics, chemistry, mathematics and the psychology of perception. How do you develop your ideas?

At the base of my work there is an incredible fascination with machines and technology: I study these tools, carrying out constant research. From the theoretical viewpoint, I’m not a scientist at all. Sometimes I end up reading scientific papers, but I approach them as if they were poems and take what I think I have understood as a starting point. Very often the same ideas come back again, even after many years. There are strong connections between all my works. In any case, when I make an installation I think of the objective I want to attain: it consists in tracing a line between an element A and an element B. I can reach my goal only through discussion, distortion of the initial assumptions, error. I don’t follow any strategy, just my personal needs. What I do stems, in a certain sense, from an egocentric and egoistic attitude.

The polarity between two elements is one of the major themes of your artistic practice. I’m thinking of a work like Inver (2005), in which you contrast two opposing elements: on the one hand a very white source of light, on the other a deeply black spot. Explain this concept better to me.

In my works I often want two conflicting elements to meet. But what interests me most is the space in between, a real physical space. This interest probably derives from my training as a landscape architect: it is possible to create spaces in the open air without erecting walls, but by grouping different units. In this way it is possible to generate median spaces, interstices between elements.

Carsten Nicolai, Snow Noise, 2001. Courtesy: Galerie EIGEN + ART Leipzig/Berlin and The Pace Gallery. Photo: Uwe Walter, Berlin.

The concept of polarity takes on other aspects in your work: it also becomes a dialectic between image and sound, as we have already seen, between order and disorder, visible and invisible.

My installation Snow Noise (2001), inspired by the essay entitled Snow Crystals: Natural and Artificial by the Japanese scientist Ukichiro Nakaya, contrasts the process of the creation of crystals of snow––a process that happens in real time thanks to a special machine––with a schematic representation of the different types of crystals on the opposite wall. There is never a complete correspondence between the real crystal and its representation, since there is always an element that escapes any categorization. In this sense, my work investigates the relationship between order and chaos, with the aim of understanding the role that “error” plays in reality. The same is true of the polarity between visible and invisible. While we exist and walk through the streets, we have no idea of how reactivity or magnetism work. Many of my installations set out to reveal these “invisible” mechanisms. A source of great inspiration for my creations has been the scientist of Serbian origin Nikola Tesla, who carried out a lot of research on the frequency and transmission of waves. He believed in telepathy…

You have an alter ego, Alva Noto, a musician active on the experimental electronic scene in Berlin. In 1999 you set up the record label Raster-Noton, you have collaborated with extraordinary musicians like Ryuichi Sakamoto and Ryoji Ikeda and you give performances of your music all over the world. What is the relationship between your activity as a visual artist and that of musician?

They are two activities that, on the outside, tend to separate. The world of art and that of music constitute two extremely different structures, based on different dynamics and systems of communication. On the creative and personal plane, however, they are not two distinct practices at all, they stem from the same pressing creative need.

To conclude, tell me something about your upcoming projects.

At the moment I’m working on a new music project, entitled Diamond Version, together with the musician Byetone. It’s a clear, limpid and highly rhythmic project. As a visual artist, on the other hand, I want to continue along the line I started on with Unidisplay: I’m thinking of extending the work conceptually, so that it becomes my new main theme of inquiry.

Carsten Nicolai, Unidisplay, 2012. Photo: Agostino Osio.

Alva Noto, Uniscope, 2011.

Carsten Nicolai, Inver, 2005. Courtesy: Galerie EIGEN + ART Leipzig/Berlin and The Pace Gallery. Photo: Uwe Walter, Berlin.

Carsten Nicolai, Pionier II, 2009. Courtesy: Galerie EIGEN + ART Leipzig/Berlin and The Pace Gallery. Photo: Amedeo Benestante

![Carsten Nicolai / Marko Peljhan, Polar ᵐ [mirrored], 2010. Courtesy: Galerie EIGEN + ART Leipzig/Berlin and The Pace Gallery. Photo: Ryuihci Maruo (YCAM Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media)](http://www.klatmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/CNMP_10_polar-m_02.jpg)

Carsten Nicolai / Marko Peljhan, Polar ᵐ [mirrored], 2010. Courtesy: Galerie EIGEN + ART Leipzig/Berlin and The Pace Gallery. Photo: Ryuihci Maruo (YCAM Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media)

Carsten Nicolai, Frozen Water, 2000. Courtesy: Galerie EIGEN + ART Leipzig/Berlin and The Pace Gallery. Photo: Uwe Walter, Berlin