18 July 2013

Candida Höfer is a German photographer, born in 1944. In 1968 she began to contribute to a number of journals, two years later becoming the assistant of Werner Bokelberg, a famous fashion and commercial photographer who today lives and works between Hamburg, Paris and New York and has immortalized people like Picasso, Dalí, Brian Jones and Andy Warhol. She attended the so-called Düsseldorf school (1973-82) and in 1976 started to develop her own idea of photography under the guidance of the legendary Bernd and Hilla Becher, seeking from the outset the beauty hidden in public buildings (over time: museums, libraries, theaters, palaces, galleries, banks, offices, waiting rooms, zoos), and became famous for several series on foreign workers in Germany. Her pictures have been shown at numerous exhibitions all over Europe and in the United States. One of the most recent is still underway in Rome, at the Galleria Borghese, until September 15: seven magnificent photographs that portray the reconstruction of the original Borghese collection.

Rome, and other places too. One of your more recent exhibitions, A Return to Italy, at Ben Brown Fine Arts in London, consisted of thirteen new photographs of buildings in Mantua, Sabbioneta, Vicenza, Carpi and Venice. A great love of Italy, it seems.

Yes, I’m in love with Italy. Anyone familiar with my work knows how attached I am to the Bel Paese. I have taken a huge number of photographs in Italy: in Naples, Bologna, Venice, Rome and many other cities. In Italy there are wonderful places, rich in history and culture: for the kind of work I do it’s the best place.

Candida Höfer, Museo Civico Di Palazzo Te, Mantova (I), 2010.

The Grand Tour, the original one, had Italy as its final destination. Where Goethe once traveled, today there are more and more Chinese tourists who arrive, camera in hand, to explore a country that is often unfamiliar to its own inhabitants. Having seen these marvels, do you have any suggestions?

I don’t know. Let’s say that I’m an unconventional tourist, who tries to go anywhere I might find something that interests me. The Vatican is a tourist attraction, for example, but it’s a fantastic place anyway. In any case, it’s not easy for me to move around, for one simple reason: I don’t drive. So I need someone to accompany me everywhere with all my equipment. I’m very lazy, and then I’m a city person. Luckily I have good friends who suggest new places to me, theaters, villas or palaces to visit.

Mario Codognato, curator of the exhibition at the Galleria Borghese, points out in an essay that what characterizes the interior of a building you have photographed is the special light that turns it into a fragment of memory, of experience, rather than just a room. How do you choose these places and how do you transform them?

First of all I have to find the location, and the search can be conducted through books or even on the internet. Otherwise, as I was saying, friends, people who know my work well, suggest particular places to me and send me snaps of them. And then it can happen that I’m invited directly, as in the case of the Galleria Borghese: it was the director Anna Coliva who called me. Then there can be crossovers, as with Mantua and Vicenza, where one place suggests another, or fortuitous and special encounters, like the one I had recently here in Rome to photograph the Vatican.

Candida Höfer, Villa Borghese, Roma (XVIII), 2012.

Have you ever arrived at the prearranged location and changed your mind?

Rarely, indeed almost never. Perhaps it only happened once.

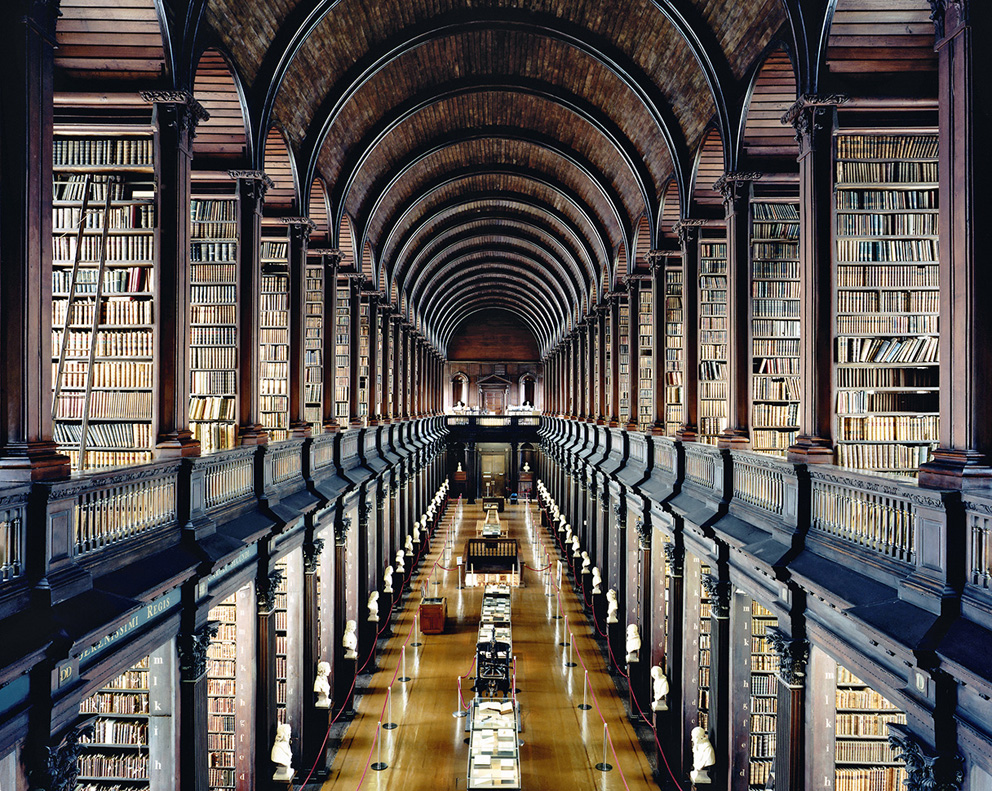

You’ve photographed hundreds of historic places and masterpieces of architecture: from the theater in Mantua where Mozart played at the age of 13 to the library of Trinity College in Dublin where Samuel Beckett and Oscar Wilde studied. Of them all, is there one series that you prefer?

As I always say, it’s the last work I’ve done that I pleases me. I can’t make lists of favorites, I love all the settings in which I do my work: if I didn’t like them, I wouldn’t even consider them as subjects. I must say, however, that in Naples there is the Biblioteca dei Girolamini which is breathtaking, and it was really difficult to obtain permission.

Candida Höfer, Biblioteca dei Girolamini, Napoli, (II), 2009.

Among the many public places there are even banks.

Banks have changed, just like libraries: there was once a time when these places had another significance. They were fascinating. This may be partly why people don’t like them anymore. Today I have really no interest in photographing them.

You have been described as an archeologist of the present, because you show that we started out from what we were, from our links with a magnificent past.

Present and past are equally important. In my photographs I speak of silence and distance. For me it is fundamental that the atmosphere, the light, the colors are grasped. Among those who look at my works there are some who find details that not even I had noticed, and that is a wonderful gift for me. This is my work and it’s what I was seeking when I chose to become an artist: being able to show people everything that I have to make them see.

Humanity is not present in any of your photographs, although it can be felt. Obviously there are exceptions that prove the rule: such as some pictures you took between 1960 and 1970, portraying Turkish immigrants in Hamburg, Düsseldorf and Cologne, or passersby in Liverpool. Why have men and women disappeared?

In the beginning I took photographs of some people, we’re talking about over forty years ago, and it wasn’t simple. Later I realized that for a shy person like me it was really hard to control people or make requests of them. So I started with some private places and found that the framing was much more discernible without people. There are no people there, but you understand that the places were made specially for them. This is very meaningful for me, and it’s exactly what I want to express.

Candida Höfer, Villa Borghese, Roma (I), 2012.

Through attentive and meticulous work, you turn your visions into perfect, ecstatic, highly accurate images. How do you see the photography of today, the pictures that everyone produces rapidly, in large quantities, and then shares through social networks?

I couldn’t say, it takes time to judge a phenomenon on that scale. Sometimes I take many pictures too and I believe that everyone has to make his or her selection. It’s important to select.

Along with Thomas Ruff, you were one of the first of the Bechers’ pupils to use color. What role does it play in your works?

An important role. At the end of a shoot, when the part in the lab starts, I look first at the colors and the brilliance, both of which are fundamental. With the digital it is great to able to control the colors, and it’s simpler. It was possible to do it with analog photography too, but it took much more time to get the color perfect and the light right.

Each of your photographs is based on an equilibrium, it seems to have been taken at the just the right time: not a moment after, nor a moment e before. How long does it take to find the point of equilibrium in the shot?

This can be a big problem, it depends on a variety of things. On the size of the room: when it’s small, it’s much more difficult to shoot, you need to have more patience with the exposure time too. It depends on the light: when there’s a lot, it’s easier, when there isn’t, as in theaters, it takes longer. For the photographs at the Galleria Borghese, taken last winter, I needed three or four days. We started very early in the morning because we had the privilege of entering just before opening time, or afterward, when everyone had left.

Candida Höfer, Villa Borghese, Roma (X), 2012.

Is there a perfect season for taking pictures?

The winter is a terrible time to take photographs: the mornings are dark and the daylight lasts a really short time. You have make the most of it. Fall or spring, on the other hand, are ideal moments for photography.

What haven’t you photographed and what would you like to photograph?

The Vatican certainly, and then I’d like to work in Asia. I have friends in Taipei and Hangzhou, I know gallery owners in Hong Kong and people working in the art world who have very interesting spaces. I’ve taken a few snapshots in China, just as I do normally, but there is another scale over there: a city with 5 or 6 million inhabitants is considered small. We shall see.

Candida Höfer, Villa Borghese, Roma (IX), 2012.

Between 1997 and 2000 you had an experience of teaching at the Karlsruhe University of Arts and Design. How was it?

Positive, but I don’t see myself as a teacher at all. The only thing I could pass on to the students was the teaching I had received in Düsseldorf: one of those schools that teaches without teaching. When I was learning it was another time, no importance was given to photography, still less to those who took and made photos. Today it’s totally different.

You’ve had mentors like Bernd and Hilla Becher. What have been, in addition to the German couple, the points of reference in your photographic research?

There have been many. Until the end of August some works of mine from a long ago are on show at the Galerie Thomas Zander in Cologne. Black-and-white photos that were attributed to this or that artist when they were exhibited for the first time: many of them are American photographers that I was studying at the time and who certainly inspired me, more or less consciously. However, I’m not one of those people who is interested solely and exclusively in photography. For me it’s also very important to look at paintings, to visit museums and exhibitions, without focusing my attention in a single direction. At times the suggestions come directly from the places. For example, when I photograph a space, a room, I let myself be influenced by the colors of the walls. I find different points of reference in everything I do and I never stop learning.

Candida Höfer, Museo Civico Di Palazzo Te Mantova (IV), 2010.

Candida Höfer, Weidengasse Köln, 1975.

Candida Höfer, Villa Borghese, Roma (XV), 2012.

Candida Höfer, Biblioteca dei Girolamini Napoli (I), 2009.

Candida Höfer, Uffizi Firenze (I), 2008.

Candida Höfer, Trinity College Library, Dublin (I), 2004.

Candida Höfer, Volksgarten Köln, (I), 1974.

Candida Höfer, Villa Borghese, Roma (XIII), 2012.

Candida Höfer, Villa Borghese, Roma (XIII), 2012.

Candida Höfer, Universitätsbibliothek, Hamburg (I), 2000.

Candida Höfer, Deutsches Hygiene-Museum, Dresden, (VI), 2000.

Candida Höfer, Palàcio da Bolsa Porto (II), 2006.

Candida Höfer, Teatro della Pergola Firenze (I), 2008.

Candida Höfer, Teatro San Carlo Napoli (I), 2009.

Candida Höfer, Galleria Degli Antichi Sabbioneta (I), 2010.