8 May 2013

The art of Adrian Paci recounts, through the force of a limpid and highly poetic language, the drama that accompanies every passage, the pain of the transit from one place to another, from a beloved and familiar reality to a new and therefore unknown world. It is a story told with painting, video and performance—a story that takes its inspiration from the personal experience of the artist, who was born in Albania in 1969 and moved to Milan in 1997. Adrian Paci, whose work—now internationally recognized—has been shown at two Venice Biennali and at the MoMA PS1 in New York, currently has a retrospective in Paris, entitled Vies en transit. A retrospective that we will have the opportunity to see, although in a new guise, at the PAC in Milan next fall.

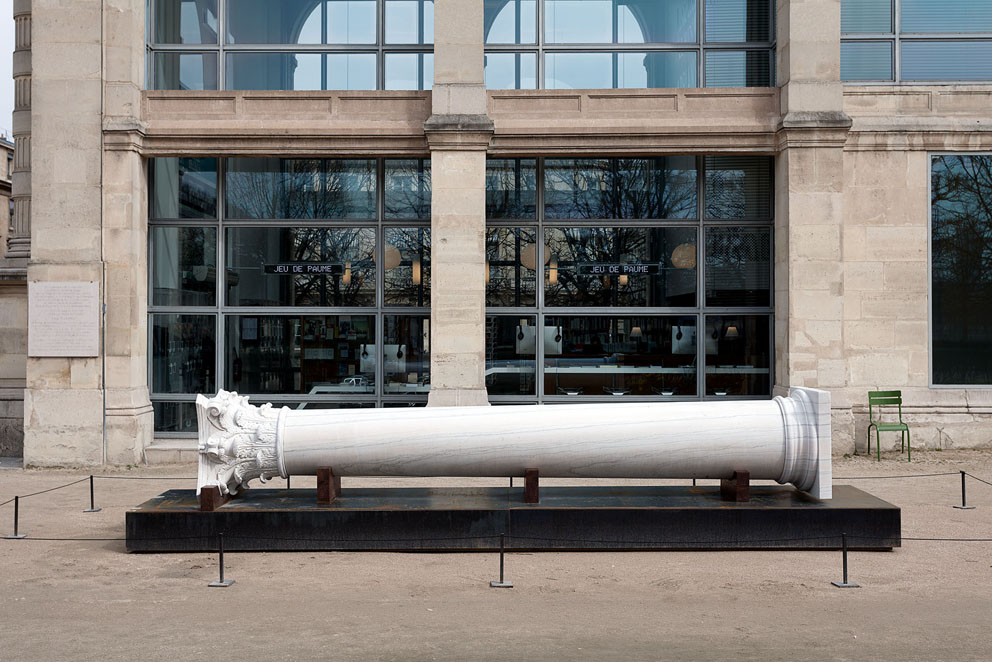

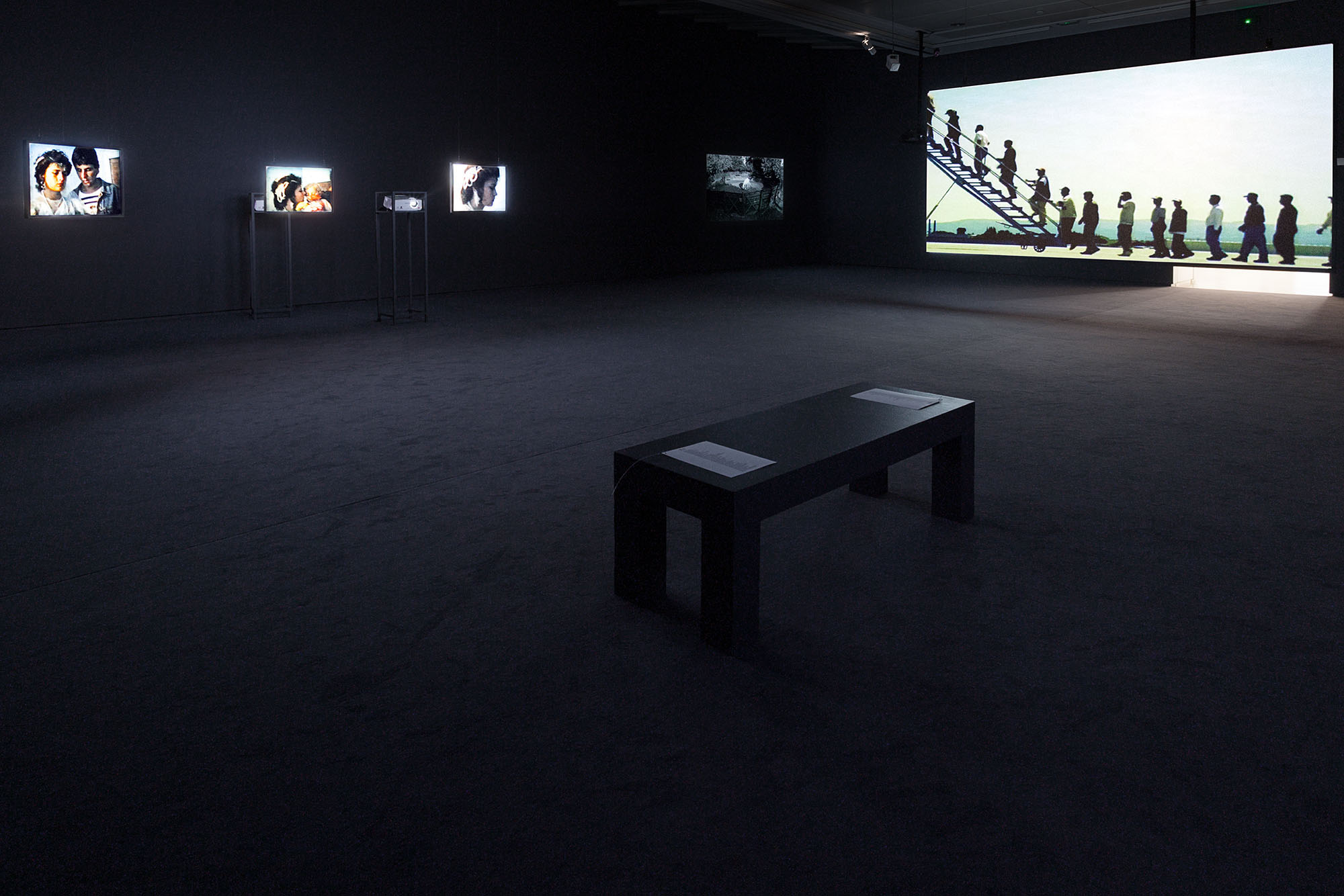

Adrian Paci. Vies en transit, Jeu de Paume, Paris, 2013. Photo: Romain Darnaud © Jeu de Paume

You were born in 1969 in Shkodër, Albania, the city that used to be known as Scutari. You came to Italy, to Milan, for the first time in 1992, at the age of twenty-two, thanks to a scholarship. In 1997 you decided to leave your country because of the political disturbances, and settled in Milan with your family. What impression did this city make on you the first time, and in what way have Italy and the Milanese artistic milieu contributed to the definition of your style?

The encounter with Italy and Milan in 1992 was fairly complicated. I came from a completely different world, and international art for me was just a pile of books. I had had no chance to visit museums or cities of art, nor to meet artists. Even my approach to the history of art was based mainly on a relationship with images, not on words or critical analysis, because the latter were always contaminated by an extremely ideological position. Since my childhood I had liked looking at the books of my father, who was a painter. I tried to get to know art outside Albania through books, or rather, through the pictures in books. This was how I tried to construct an artistic culture for myself that was different from the one imparted by the regime. I arrived in Milan the first time with many hopes and expectations. Having obtained a scholarship, I belonged to a privileged class: I lived in a lodging house and went to a school. I studied Art and Liturgy at the Scuola Beato Angelico in Milan. I came from a country that was perforce atheist, but I had a very high opinion of sacred art. This dimension of spirituality had been completely denied to us during the years of communism: I was looking for something new, but this thing had to possess a strong spiritual charge. At the Scuola Beato Angelico there was also an Art College, at which the students did exercises with color and abstract forms—something I had never done during the years I spent at the academy in Albania because I had always worked on the human figure. But I was disappointed when I saw the work of these students: they conceived the abstract only as a play of colors, surfaces and forms. Whereas I saw it as the fruit of research into a deeper dimension. With respect to the traditional style of socialist realism, what was new for me was abstractionism, the nonrepresentational, the liberation of gesture and expressiveness. Something that in Italy had been out of fashion for years. It was as if I felt betrayed in my expectations about the genre of art that I wanted to practice and understand better.

Adrian Paci. Vies en transit, Jeu de Paume, Paris, 2013. Photo: Romain Darnaud © Jeu de Paume

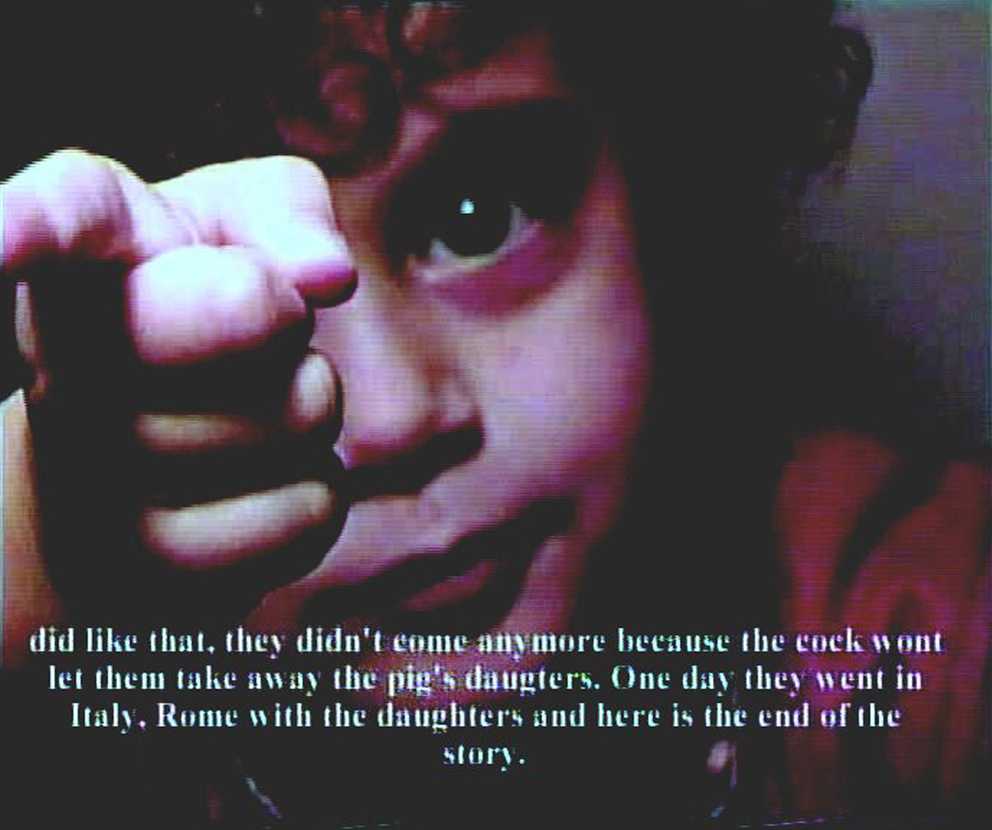

In Albania you studied painting, but the first work with which you attracted international attention was a video of 1997, Albanian Stories, presented two years later at the Venice Biennale. The protagonist of the work is your daughter Jolanda, who uses the language of the fairytale to talk about the dramatic political situation in Albania and tell the story of your move to Italy. How did you come to the medium of video?

I came to video somewhat by chance. Video was not the objective: the aim was to find out what I could do, where I could place myself in the discourse of art. Albanian Stories was born out of this continual research. During research like this things can happen, you might end up faced with a situation that is worth observing and representing. This is what happened with my daughter’s stories. I couldn’t paint them or draw them or photograph them: I had to film them. The force of that video does not lie in me as an artist but in what took place in front of my eyes. It was a great lesson: as an artist you don’t have to talk to others about your problems, or show your skill or your deficiencies, your virtuosity or your incapacity. What you have to do is establish a relationship with something. Video was the filter needed and the most immediate one—it doesn’t indulge itself as a medium, nor does it set out to gratify its author.

Adrian Paci, Albanian Stories, 1997. Courtesy: Adrian Paci and Kaufmann Repetto, Milan.

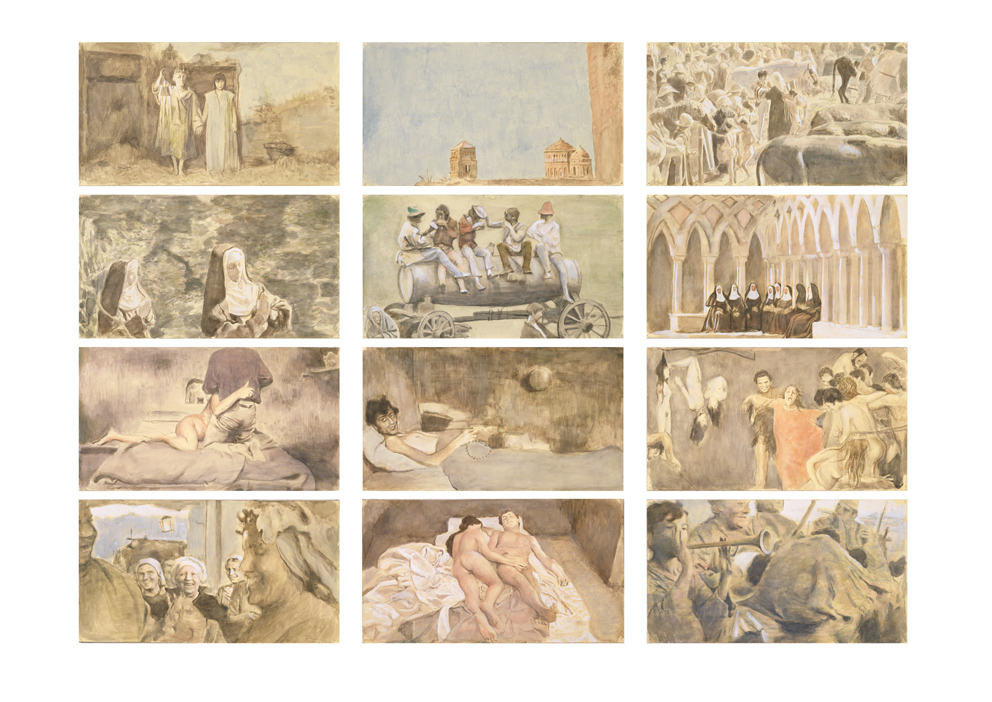

You often start out from the video image and rework it in painting—I’m thinking of the series of paintings based on footage of Albanian marriages or the works inspired by Pier Paolo Pasolini’s The Gospel According to St. Matthew. You once said you saw painting as a primitive and less costly form of cinema. What is the relationship between painting and video in your work?

As soon as I started using video—a medium about which I knew nothing from the technical point of view, but which turned out to be so successful, so effective in conveying that experience—in a sense I brought into question my relationship with painting, which I had practiced and studied for many years. So, after my first videos—not just Albanian Stories, but also Believe me I am an artist, Piktori or Apparizione—I took a different attitude toward painting. It became simpler, more direct, less concerned with constructing the image and more interested in expressing something imagined: like a voice reading a text that has already been written. Thus my paintings seek to respond to images that already exist in a dimension of film: my first action as a painter, therefore, is to seize hold of the image, wresting it from the continuous flow of the video.

Adrian Paci, Secondo Pasolini (Decameron), 2007. Courtesy: Adrian Paci e/and Kaufmann Repetto, Milan.

Adrian Paci, Secondo Pasolini (Decameron), 2007. Courtesy: Adrian Paci and Kaufmann Repetto, Milan.

Edi Muka has described your art as a “transposition” of images from one medium to another: like in a mathematical equation, you move the image to the other side, changing the sign of its recognition. The idea of transposition alludes to that of passage, of the journey and the transit. Not coincidentally, the title of your retrospective at the Jeu de Paume is Vies en transit. You made your latest video, The Column, for the exhibition: it tells the story of the transformation of a block of marble into a column aboard a ship that is sailing from China to Europe. And the theme of immigration, at the center of your work, is also connected with movement…

Immigration, more than a theme, is an experience of life for me. It doesn’t interest me so much as a politically and socially topical subject, but as a moment of passage of an individual from one context to another—an individual who in this passage brings himself into question as well as the place for which he is headed. And I try to talk about it not through concepts or abstract forms, but through concrete facts, the details, the peculiarities of the individual situations. Understood in this sense, immigration represents, in my practice, one of the possible variations on the theme of passage and transit. If I think about my work, about the relationship between video, photography, painting and performance, I find this dimension of passing and transformation: I don’t look for closed or definitive forms, but am interested instead in their mutual relations. The video The Column stems from a story told me by a friend: the story of a sculpture that could be produced on a voyage from China to Europe, on a ship. The video tackles the questions of work, of the circulation of goods and ideas, of the relationship between East and West—all located in a non-place and a non-time.

Adrian Paci, The Column, 2012. Courtesy: Adrian Paci and Kaufmann Repetto, Milan.

Many of your works describe the rituals and traditions of your country, as if you wished to crystallize ancient gestures and ceremonies in an image. What value do you assign to the gesture, to the past and tradition in your practice?

The gesture is a figure, a trace. Age-old traditions are crystallized in the gesture, and so it takes on a ritual value. I’m thinking of the handshake in The Encounter and The Visitors, a symbol of the need that every man has to relate to the other. As an artist, I want to celebrate this gesture, to pay homage to it and raise questions about it. On the subject of tradition, I find the idea of the new at any cost, of its celebration as a value, to be stupid. I myself come out of the failure of two models of newness: the communist myth of the new man and the capitalist one of prosperity, of the free man in the age of the consumer society. Following this twofold failure I started to look for a new model of humanity, one that would be linked to tradition, not out of a nostalgic desire for a return to the past, but to find something essential, archaic, original—and so close to humanity at any time.

Adrian Paci, The Visitors, MAXXI, Rome, 2012.

The theme of being an artist is at the center of some of your works, like Believe me I am an artist and Piktori. What does being an artist mean for you? What is the role of art in contemporary society?

I don’t feel myself to be an artist who has understood his role in the world and proclaims it to humanity; on the contrary, I belong to that category of artists who never get tired of seeking, of trying to identify their position. I believe that the artist has a responsibility to art, understood as language—and so to its different expressions like painting, performance, video—every time he creates a work. In addition, he has a responsibility to the world, to people and nature; without forgetting the one to himself and his private world. Practicing art, for me, is an incessant questioning: how should I conduct myself with the language, with myself, with others, with the world?

In the fall your retrospective in Paris will come to the PAC in Milan, and in September you’ll be taking part in the Thessaloniki Biennale. What projects do you have in mind for the future?

At the moment I’ve a great desire to paint. I have several works in mind, including some videos. I can’t wait to be freer and to spend time in my studio every day, on a regular basis. I’d like to have more time to reflect, in silence, without too many telephone calls or emails!

Adrian Paci, The line, 2007. Courtesy: Adrian Paci and Kaufmann Repetto, Milan.

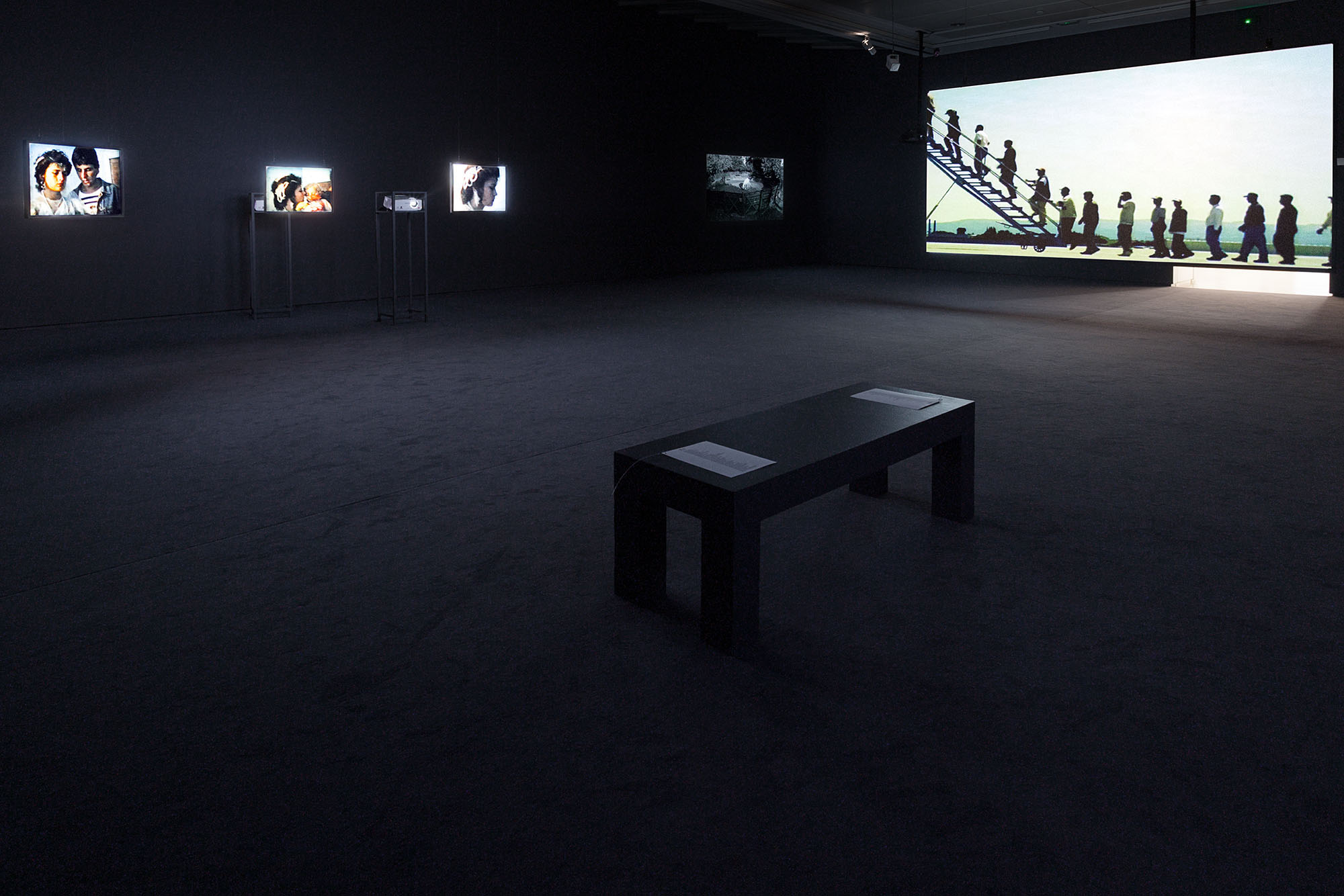

Adrian Paci. Vies en transit, Jeu de Paume, Paris, 2013. Photo: Romain Darnaud © Jeu de Paume

Adrian Paci, Apparizione, 2001. Courtesy: Adrian Paci and Kaufmann Repetto, Milan.

Adrian Paci, Secondo Pasolini, 2010. Courtesy: Adrian Paci and Kaufmann Repetto, Milan.

Adrian Paci, Centro di permanenza temporanea, 2007. Courtesy: Adrian Paci and Kaufmann Repetto, Milan.

Adrian Paci, Albanian Stories, 1997. Courtesy: Adrian Paci and Kaufmann Repetto, Milan.

Adrian Paci. Vies en transit, Jeu de Paume, Paris, 2013. Photo: Romain Darnaud © Jeu de Paume