3 October 2013

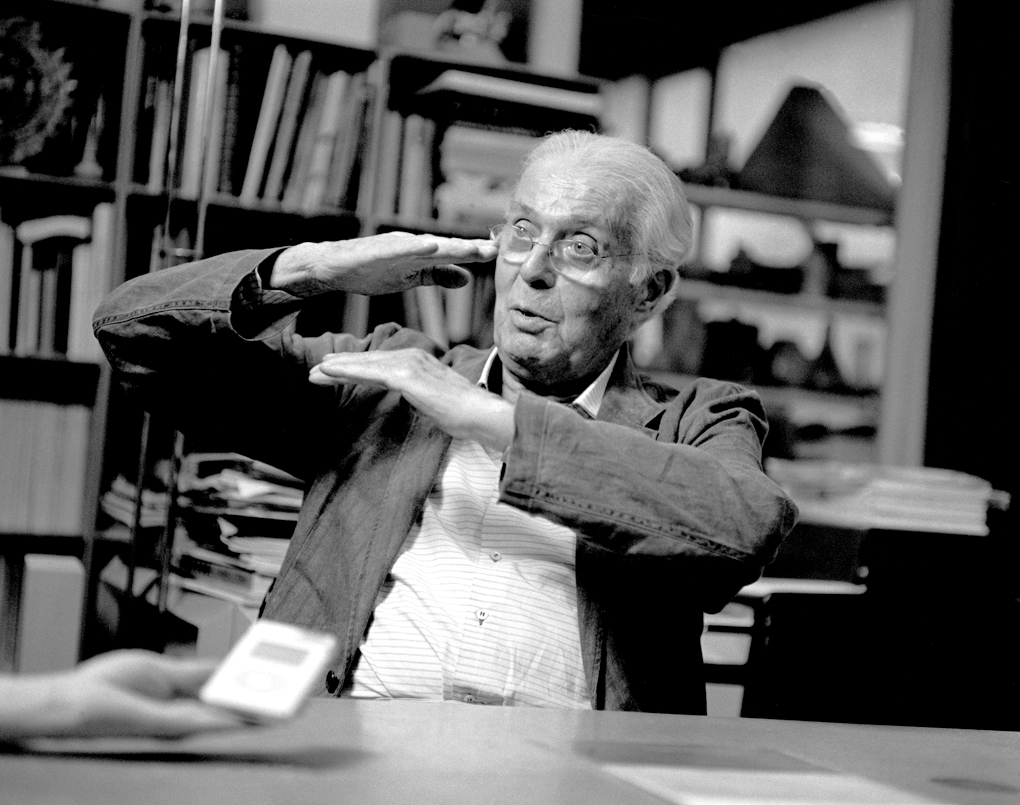

In the dense jungle of the Mato Grosso, in Brazil, there is a very rare kind of wood of a purple color that only a few people have seen. “It was something out of this world. I had brought a few pieces home, and treated them like gold. I polished it, stroked it; it was like touching glass. Despite taking every possible care over it, the wood vanished. Somebody stole it, but to tell the truth I’d have stolen it too. To go to a place like that, in Brazil, in the midst of vegetation where you don’t even know where to put your feet and you risk falling over with every step you take, you have to be off your head. Or have a wooden head, like me.” Pierluigi Ghianda, the cabinetmaker from Brianza who together with the architects of the Polytechnic has written fundamental pages in the history of Milanese design, has a wooden head and heart. Ghianda—appropriately, the name means “acorn” in Italian—is a living legend. Born in 1926, he is known not only as the poet of wood, but also for the eclecticism of his art, which reaches extraordinary levels. He has collaborated with some of the most famous designers in the world on furniture, objects, prototypes… Among others: Gae Aulenti, Mario Bellini, Cini Boeri, the Castiglioni brothers, Ettore Sottsass, Richard Sapper, Eileen Gray, Aldo Cibic, Slegten & Toegemann. And then the companies: Hermès, Rolex, Knoll, Classicon, Dior, Memphis, Rochas, Pomellato, De Padova, Loro Piana and many others. From his hands have come the historic desk of the Crespi family at Il Corriere della Sera, the first prototype of Vico Magistretti’s Vidun table, a masterpiece of dovetailing, and Cardinal Carlo Maria Martini’s library at the archbishop’s palace in Milan. Dressed in an impeccably tailored suit and seated at the desk of his studio at Bovisio Masciago, part Renaissance workshop and part alchemist’s laboratory, Pierluigi Ghianda is surrounded by thousands of objects (all made of wood, obviously), a few books, family photographs and the scent of pear, ebony and rosewood.

Workshop. Photo: Patrizio Saccò.

Let’s start with your hands. How are the hands of the man who signs wood, as you were dubbed in Studiolabo’s documentary L’uomo che firma il legno?

They’re all right now, because they no longer touch wood, but they used to be full of cuts. All carpenters and joiners worthy of the name, the ones who practice the craft out of real interest, have hands like that. But I’m talking about my generation: with today’s machines you no longer need to know wood. They do the work for you. They stop, reflect and decide how to cut. All you have to do is set up the computer, insert the piece, press the button and wait for the finished object to come out.

But what does wood mean to you?

For me wood has an unlimited value, woe betide if you spoil a piece. Because all wood, unlike metal, is precious: it’s a gift from God. Once some ladies from New York who were wandering around the workshop asked me the same question. I came out with something I can’t even remember now and they took it like a Confucian saying or a poem. But it’s enough for you to know that when someone asks me “what do you do for a living?,” I simply answer: “I’m a carpenter.”

Trays, design by Gae Aulenti. Photo: Marirosa Toscani Ballo.

This summer you went to Japan, where on June 27 the exhibition Gli artigiani [“Craftsmen”] opened at the Cassina IXC showroom in Tokyo. Your passion has taken you all over the world, both for exhibitions and on an almost endless quest for rare types of wood. What is the place closest to your heart?

I’ve been to Japan many times. There cabinetmakers are called “the craftsmen of God,” because there is a different, almost sacred view of this craft. I travel a lot for my work, even though now, given my age, I find it very hard. Let’s say that the whole world is beautiful, including the poorer countries, places where when you look around you can’t understand how people manage to live. But the place closest to my heart, obviously, is Italy.

What is a typical day for Mr. Ghianda?

My typical day has always been the same: I wake up, look at the clock and realize that it’s already too late because the work had to be finished and delivered the day before. In the absence of a timesheet, one of my assistants once wrote down in pencil the number of hours he had put in in a day. “But how many did you do?” I asked him. And he said: “Twenty-five, I went home at one in the morning.” In Brianza before the economic boom there was work and nothing else. With affluence, the young started to prefer automobiles to the hand plane. But I think that before that there were only three cars in Bovisio Masciago: the mayor’s, the doctor’s and the shoemaker’s.

Who does the Ghianda workshop work for today?

Mainly for Hermès, as it is the only company that aims at unconditional quality. Their articles are perfect. Not that there aren’t companies in Italy that produce quality furniture, but nowadays houses are hardly furnished at all: we find them with everything ready, and the level has gone down.

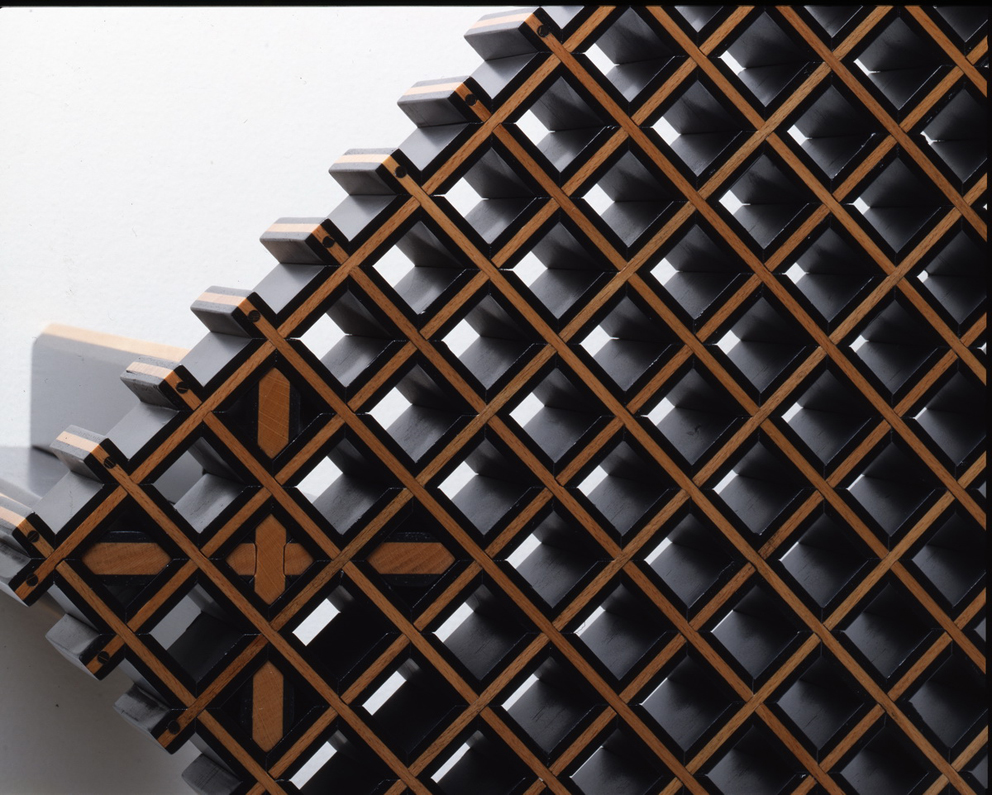

Kyoto, design by Gianfranco Frattini. Photo: Marirosa Toscani Ballo.

Who is responsible for this loss of quality?

The fault lies with society, which demands everything at once. In addition, technological progress does not sit well with craftsmanship. Quantity takes precedence over quality, plastic over noble materials. The skill of the craftsman has not vanished, but it has been drastically reduced: only a few today achieve perfection, excellence. To make a handcrafted object properly takes hours and hours of work, whereas the machine does it in a moment: it’s not the same thing, but it does it. As a result, the mastery of the craftsman is doomed to extinction.

You have worked with the historic names in Italian design. What is left of that tradition?

Nothing. The needs of the clients have changed, and there is no longer anyone who understands that to make a dovetail joint instead of using a nail really makes a difference. Today the only people come to us are the ones with old houses or houses to restore. There are only a few of us who know how to do certain works by hand, but even people with money prefer to spend it on other things. They end up buying another car or an airplane.

Hanging on one wall, along with photographs, there is a drawing by Ettore Sottsass. What relationship did you have with him?

I got to know him when he was already getting on in years, but I learned a lot from him all the same.

Bookmark. Photo: Marirosa Toscani Ballo.

You knew Gio Ponti too, who used to come to see your grandmother in the workshop. How do you remember him?

The first time I met Gio Ponti I can’t have been more than fifteen. I was in the old workshop, and my grandmother was receiving some foreign clients. Gio Ponti was standing a bit to one side. Everyone was talking about prototypes, and at a certain point he came up to me and said: “Samples cost less than prototypes, tell them to make a sample.”

The love of wood, a passion that has lasted for generations. Where did it come from?

My father, who died young, carried on the tradition of my grandfather Luigi. But the origins of the workshop date all the way back to the beginning of the 19th century. There are documents that attest to its cabinetmaking activity. One of the earliest items in the catalogue was a folding music stand that dated from even before the Risorgimento: we supplied the accessories for a piano factory in Vienna. Today the firm has about ten employees, all the children or grandchildren of former workers, because the workshop has always been a family affair.

In psychoanalysis wood symbolizes above all the relationship with the mother, because it is associated more than other things with growth and maturation. What sort of tie do you have with your family roots?

During the war, the firm was entirely in the hands of my mother Serafina. A special woman, a true matriarch. All she had to was say: “Is there any water?” and three of us were already on our feet. My daughter Beatrice takes after her a lot. She’s the only one of my three daughters who takes an interest in the workshop. She looks after everything, from the materials to the orders, from the accounts to the clients, and is the custodian of family lore.

Some extraordinary objects have passed through your hands, like Gianfranco Frattini’s Kyoto table (1705 joints to create a texture with 1600 holes), Gae Aulenti’s frames for the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, Mario Bellini’s Étagère and dozens of other historic pieces. Is there an object of which you’re particularly fond?

What can I say? We’re talking about an entire life. But everything started with the setsquare. To be hired or to go from being a shop boy to a worker, you had to know how to make a setsquare, it was obligatory. And you had to do it as well as possible, because many people were going to assess it, looking at it from every point of view. The result had to be up to the standards of the master: excellent. To obtain that result you made a lot of trials, attempts, finishes; you had to acquire perfect manual skill. When clients spoke to my mother, in the workshop, they always said to her: “Don’t forget, just a bit of wood and a lot of labor.”

Setsquare. Photo: Mauro Donzella.

Étagère, design by Mario Bellini. Photo: Marirosa Toscani Ballo.

Desk organizer, design by Gae Aulenti. Photo: Marirosa Toscani Ballo.

Frames, design by Gae Aulenti for Musée d’Orsay. Photo: Marirosa Toscani Ballo.

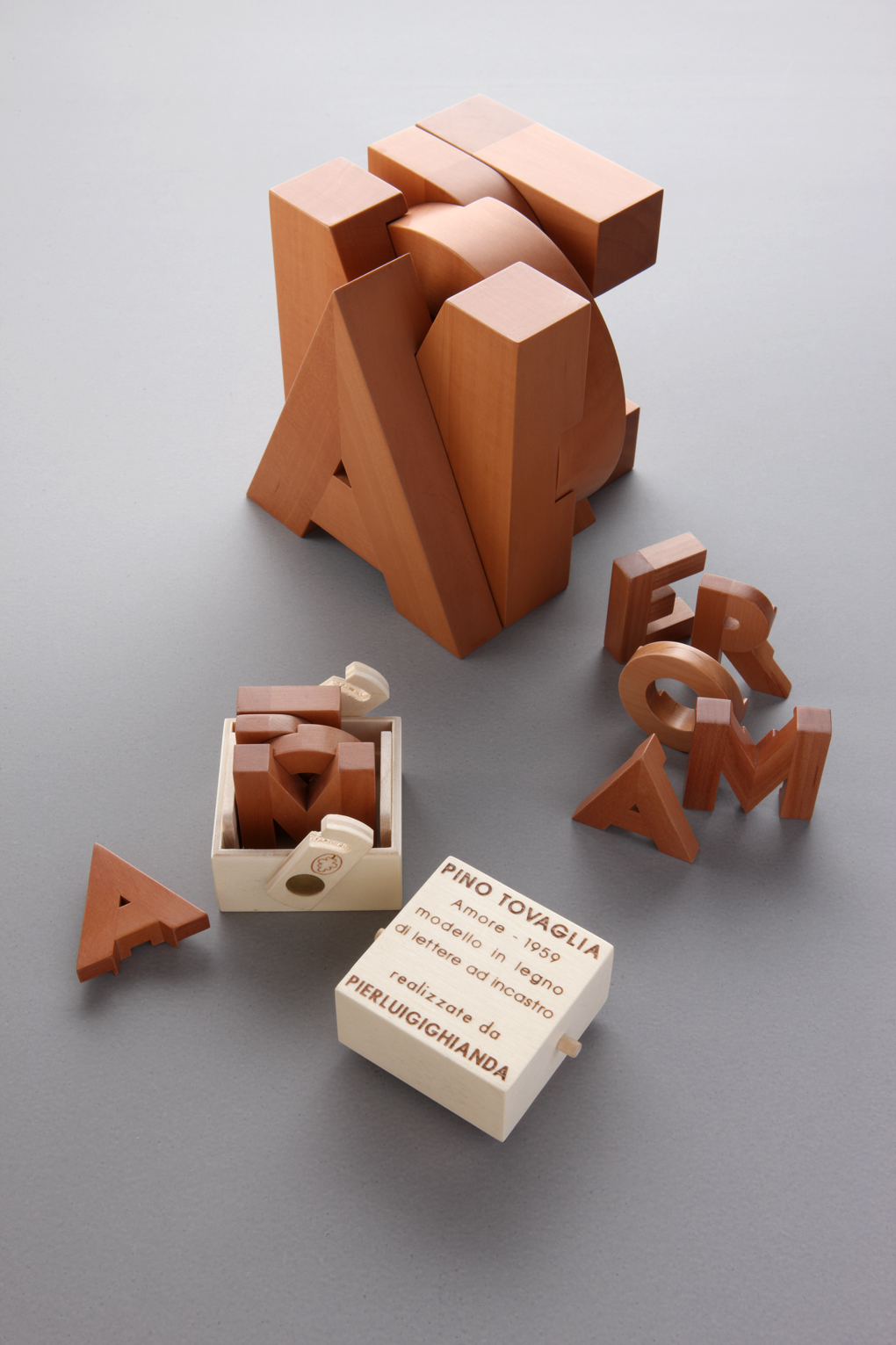

Amore, design by Pino Tovaglia. Photo: Marirosa Toscani Ballo.

Photo: Giancarlo Pradelli.

Photo: Giancarlo Pradelli.

Photo: Giancarlo Pradelli.

Photo: Giancarlo Pradelli.

Photo: Giancarlo Pradelli.