22 October 2013

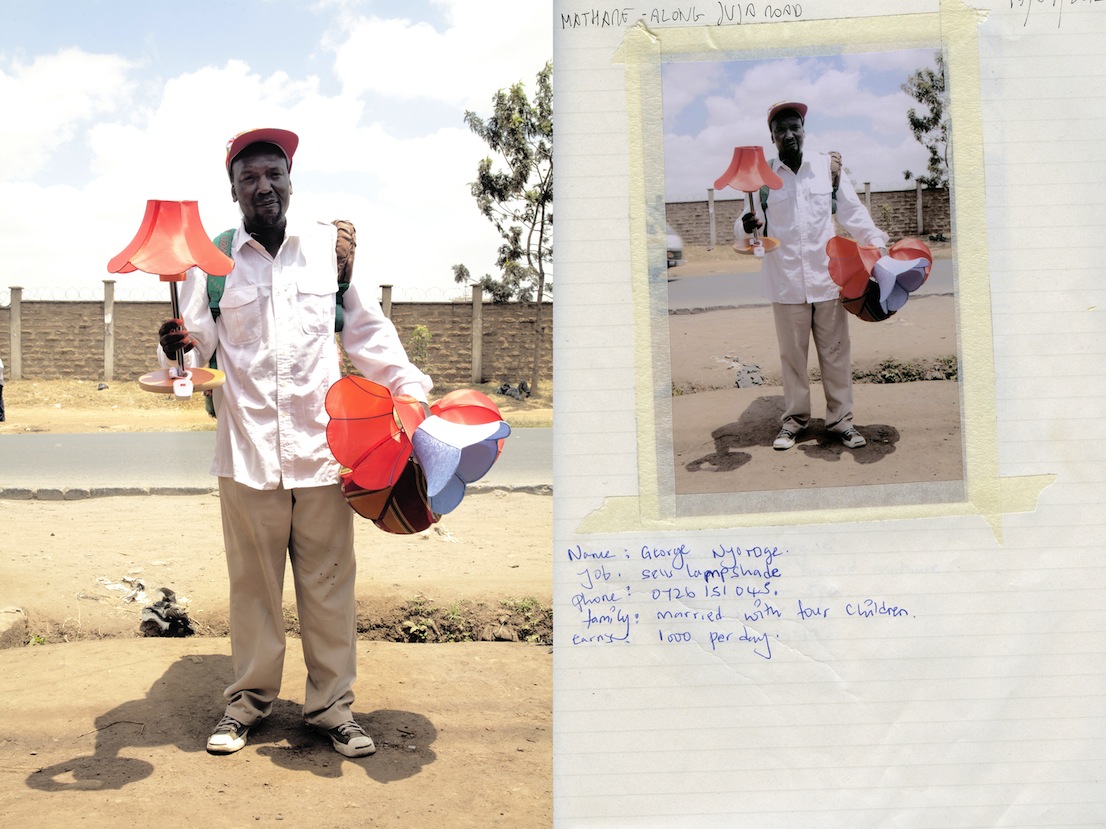

If they were not among the most hackneyed buzzwords of the moment, self-production and the rediscovery of craftsmanship would be ideal keys to the interpretation of Francesco Faccin’s work. But it is precisely the recent popularity of this approach to design that makes a preamble necessary. Faccin, born in Milan in 1977, has shown an interest in the crafts since way back, and with a determination very rare among the designers of his generation. His is the commitment of an authentic researcher, and for him the level of inquiry continues to play an essential role quite apart from the material results of individual projects. To take just one example, Faccin has just opened an exhibition at the Milan Triennale, Made in Slums. Mathare Nairobi, devoted to an assortment of highly unusual objects of which he is not the author, but the collector. Objets trouvés from a place where the glut in consumption produces its most pernicious effects. An African slum that can almost be seen as a submerged iceberg of which the West is the visible tip. Unknown territory for most, but one where something is moving amongst the garbage and, luckily, not just rats and parasites.

Made in Slums. Mathare Nairobi, Triennale di Milano. Photo: Filippo Romano.

Can you tell us something about this story?

Mathare is a shantytown in Nairobi that houses half a million people, practically a city within the city of the Kenyan capital. I went there in October 2012, invited by the NGO Liveinslums to design and realize the interiors of a school. Spending every day in the community, I realized that a multitude of stalls immersed in the mud were displaying goods that I had never seen before. I mean articles of everyday use that the artisans of the slum assemble, make and sell; things that are literally born out of the garbage that invades the whole of the surrounding space. However absurd it may seem, a shantytown like Mathare in fact “lives off” garbage, because where there is waste there are resources that can be reutilized, not just food but also and above all material.

What do they make out of it?

All sorts of things. In part imitating industrially made consumer goods—buckets, watering cans, saucepans—and in part creating new models. The common denominator, however, is necessity: in everything they invent or re-create there is no concession to decoration.

Don’t you think that the rhetoric of design is risky for the other 90% of the world? Instead of getting their hands dirty on the spot, many prefer to stay in their studios and send designs from there to the underdeveloped countries.

Sure, because then you go there and you realize that in the slum, for example, there is no electric current, which is not exactly a minor detail if you have to make wooden furniture. You have to work with a handsaw and aluminum nails that bend if you just look at them, and this scarcity forces you to redefine the whole process of production, trying to avoid any waste of material and energy. The most important element of my project was probably a sort of assembly line made up of a template with various blocks of wood to hold the strips so that they could be glued in the right position. But it’s not that I went there simply to take them my template: I constructed it with them and explained how it worked to the people who were going to use it. Now they send me pictures of the range of objects they have developed using this tool.

Made in Slums. Mathare Nairobi, Triennale di Milano. Photo: Filippo Romano.

So it is not a matter of the usual cobbling together of recycled pieces, but of a parallel economy made up of products created and replicated on the basis of the law of demand and supply. How important is the concept of necessity today?

The question of the necessity of an object in our lives is I think the only real one that we have to ask ourselves as designers. We go on racking our brains over the crisis in the design system, but the problem is not the system of industrial production as such or the fact that less is being sold. Design is in crisis because we no longer know what is necessary. People think that a product that sells is a good product, but this kind of thinking leads to great confusion about the actual value of things.

In practical terms, what alternative are you seeking?

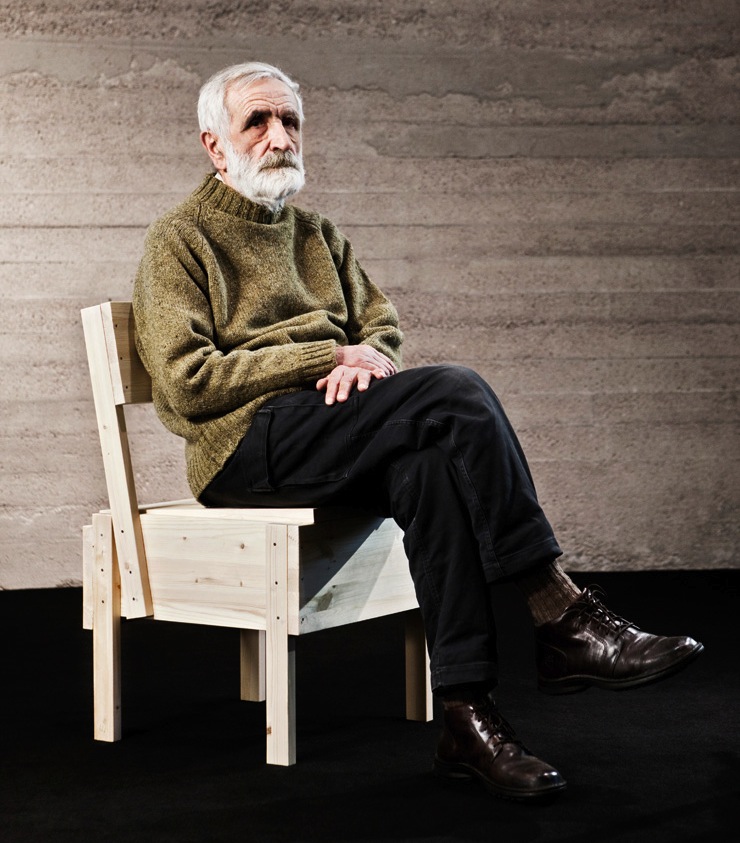

When I’m called on to design something, be it a wheelbarrow or a restaurant, I always try to tackle the job in such a way that the main point of interest is not the final object, but the process. As in the case of the 28 Posti restaurant in Milan: I’m very satisfied because I’ve had very few comments on the aesthetics of the furniture and a lot on what went on behind the scenes, on the involvement of convicts from San Vittore in the construction of the pieces. This for me is a response to the complete lack of reflection on what it means to design today. Then the dream is that each design should be a page in a coherent story, that there should be a guiding thread leading beyond the success of a single product on the market.

28 posti. Photo: Filippo Romano.

So let’s tell this story of yours. How did you start, what schools did you go to?

In the first place let me say that the schools should all be closed: I think that to do this job there is no need at all to attend a school. The only thing that counts is the chance to meet people who want to practice the same profession as you. In this sense, the IED in Milan is the only truly international school: there I met Alvaro de Ocón, who became not just my best friend, but also a partner with whom to construct “our” idea of design. We have been complementary for a long time, using the years of our training to devour images, exhibitions and places, traveling all over, from London to South America.

What styles and what examples have influenced you?

I’ve had my love affairs. One of the first was for minimalism. Then the phase of excessive severity passed and on a trip to Mexico I discovered Luis Barragán: it was love at first sight without reservations. I don’t consider him just an architect, but an all-round designer, because he thought of the house as a place of relationship between human beings, as a reflection on proportions and thicknesses, on materials and light. He was a master of complexity and through his work you understand that when architecture is done well it does not concern the form of spaces, but the life that goes on inside them. Perhaps it is because of this degree of complexity that I have looked for my teachers more among architects than among designers. Architects capable of designing not walls, but sensations.

Who else, for example?

One designer who has changed my life is called Giuseppe Galimberti, and he is an architect who has spent his whole life in Valtellina, creating unknown masterpieces. He is a Barragán of North Italy. He works with traditional structures, using concrete and stone in a totally innovative way and building houses for cultured clients able to grasp their significance. And he’s never come down from the mountains. He lives up there with his wife and his goats, and you can’t find even a trace of him on the internet. There I realized that you can do things of very great quality without putting yourself on show.

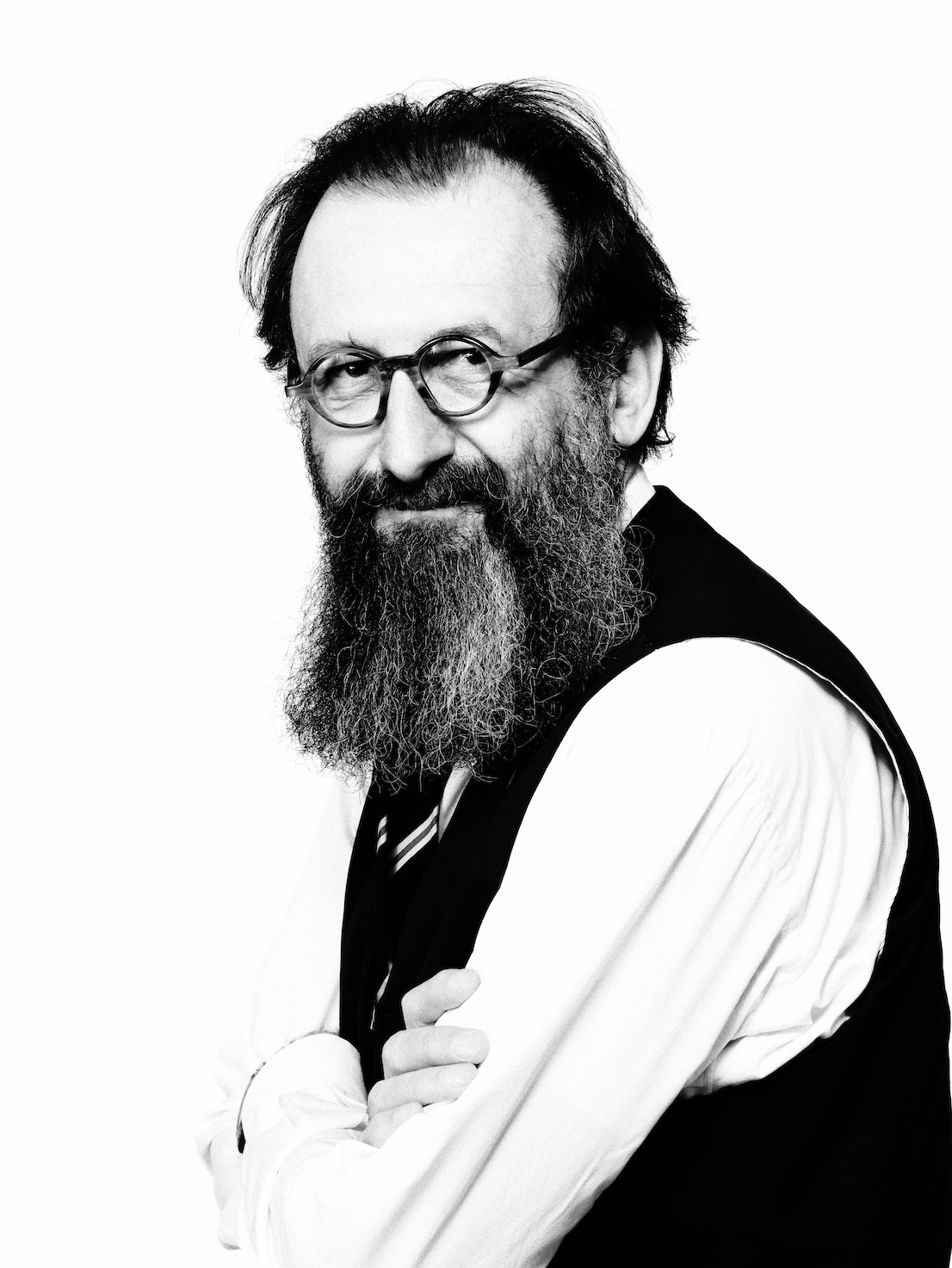

How did you meet Enzo Mari?

I wrote him a letter, completely by hand, and sent it by snail mail. I wrote to him because he’s the only one in Italy who embodies the attention to detail, quality, material and traditional knowhow to be reinterpreted. In addition he was the only designer in Milan who worked without using the computer, an instrument that I hated too. So two weeks later I got his answer, written with a black felt-tip pen, in which he invited me to come for a chat. The meeting didn’t go at all well: he slated everything I’d done up to that moment, but thinking back on it he had a point.

Enzo Mari. Photo: Jouko Lehtola.

He must have spared something…

He liked the assemblages that I made with salvaged materials, more a work of “art” than of design. Then and there he sent me away, as bluntly as only he can be. But a week later he called me and gave me a chance: six months working in his archives, cataloguing articles in magazines and newspapers by means of a system of index cards with brief summaries that he had developed himself. In the end, in the last few months, he put me to work on the Mariolina for Magis. Obviously all laced with his proverbial moodiness. So that in the end I went away convinced that I would never be a designer.

And what did you think you would do instead?

I looked for a job where quality would depend more on doing than on thinking. So I apprenticed myself to a craftsman. In reality he was an architect who had gone to the instrument-making school in Cremona and had a “cultured” vision of the crafts. Together we built a large number of architectural models: beautiful objects, all made by hand out of high-quality solid wood, working in a 19th-century spinning mill where the atmosphere was decidedly that of the Renaissance.

And there you were able not to think?

I learned to use chisels, to work just with my hands without thinking about the design. Thanks to this experience my creative process today involves constructing rather than drawing. I don’t work with the computer anyway, and I’m not good enough at drawing to express myself fully with it, so the material approach of the model is the one that suits me best. I have to construct things in order to understand them, so I often create objects without drawing them first. Then once I’ve made the prototype I produce a technical drawing from it. The Centrino table, for example, I built first and only “designed” afterward. In the beginning I felt this method to be a limitation, as if I were a sort of illiterate of design. Later I understood that it is simply my way of thinking.

When did you begin to feel you were a designer?

After the 2010 Salone in Milan, when I took part in the Satellite with Alvaro de Ocón: the Stratos chair was taken up by Danese, I attracted the attention of the press and I won the Design Report Award. That was when I realized that I could give it a go.

Stratos, design by Francesco Faccin for Danese, 2011.

Recently you’ve taken part in many joint projects, in which the crux is the establishment of relations. You’ve developed the ability to put yourself at the service of a collaborative project, which is a quality typical of the craftsman.

For me the fundamental thing is to find an ethical approach to the project in which I’m involved. If a bank called on me to design its head office, I would ask myself how to do it in the most ethical way possible. I would ask myself, for example, what is the role of the bank today in the West.

As another of your teachers, Michele De Lucchi, has done.

Michele is much more of an entrepreneurial designer, although for him too reflection on the crafts is crucial. He has the ability not just to satisfy his client, but to become his client, to identify with him. But I have another outlook: I believe that in your choices you should not try to be of broad appeal, but radical. Essentially I look for clients who will give me the opportunity to tell my own story.

But then why did you turn to De Lucchi?

Because I had decided that I wanted to work with industry, that the craft dimension was no longer enough. And in Italy Michele seemed to me the designer who best straddled the worlds of the crafts and industry. It goes without saying that I contacted him too with a handwritten letter.

Why do you think everyone is talking about the crafts today?

With the industrial system completely in crisis, the only way to go on producing objects is to turn to those who know the materials and can realize designs. If the doors of industry are closed, then the crafts are the only alternative. Craftsmen are the only ones who still have real skills.

People talk about the crafts and put together things that are very different from one another: the phenomenon of makers, of 3D printers. What do you think of them?

It’s a new form of production, but it’s probably not correct to talk about crafts. We don’t know how this phenomenon will evolve, from this point of view we are still in the Stone Age. However, the idea that one day we are going to print our own refrigerator at home seems to me ridiculous. If for no other reason than by that time the fridge will very likely be an obsolete product, replaced by who knows what.

Francesco Faccin for “Why not” Academy. Photo: Filippo Romano.

So industry in crisis, the crafts in crisis. What is the third way?

If we’re talking about the crafts proper, the highly specialized kind that works without a designer, then it’s natural that it should be in crisis. I’ll give you an example: this year in Rome I worked on a systematic mapping of quality craft workshops. This opened my eyes to a harsh reality that is hard to accept: up until a while ago the craftsman was at the service of an urban fabric that had a continual need to mend things and buy new ones, whereas today he works almost exclusively for tourists. The basket maker used to provide a real service, he made baskets to hold the laundry when you did the washing, not to sell to tourists as something pretty to put fruit in. So today certain crafts are dead because the needs that kept them alive are dead. Then it’s clear that some niches survive: the Chiavari chair will go on being made as a product of the highest quality, an excellence unique in the world. But it is and should be a rarity, not the norm.

Right now what would you like to be designing?

I don’t have a favorite type of object. The more things frighten me the more I think I ought to tackle them. In this sense the thing most alien to me is the computer, but if I had to design one I’d accept the challenge and set about studying the problem. For it is usually in these “uncomfortable” situations that you make the leap toward something really different. When they offered me the chance to go and design in Africa and make the furniture for a school in the slums, or when they told me to go and work in a prison at Bollate, I was terrified too.

How much does the material influence the design? I’m thinking not just of your many objects made of wood, but also of the bowls made of an extraordinary bioplastic derived from the waste from the process of milling rice…

I think the material ought to determine the form of things, and in fact I can’t bear it when certain materials are misused. I’m thinking, for example, of two buildings in Rome, very close to one another, Pier Luigi Nervi’s Palazzetto dello Sport and Zaha Hadid’s MAXXI. In the latter, concrete was used in a wholly improper way, requiring it to make an effort to support the forms desired by the architect. In Nervi’s case, on the other hand, the concrete is self-supporting, it was designed in that form for reasons of statics. Well, for me the ultimate is when aesthetics and structure coincide, or rather, when the structural element is beautiful precisely because it exploits the natural potentialities of the material.

Made in Slums. Mathare Nairobi, Triennale di Milano. Photo: Filippo Romano.

Made in Slums. Mathare Nairobi, Triennale di Milano. Photo: Filippo Romano.

Centrino, design by Francesco Faccin for Bolia, 2011.

Michele De Lucchi. Photo: Giovanni Gastel.

Made in Slums. Mathare Nairobi, Triennale di Milano. Photo: Filippo Romano.

Made in Slums. Mathare Nairobi, Triennale di Milano. Photo: Filippo Romano and Francesco Giusti.

Made in Slums. Mathare Nairobi, Triennale di Milano. Photo: Filippo Romano and Francesco Giusti.

Made in Slums. Mathare Nairobi, Triennale di Milano. Photo: Filippo Romano and Francesco Giusti.

Made in Slums. Mathare Nairobi, Triennale di Milano. Photo: Filippo Romano and Francesco Giusti.

Made in Slums. Mathare Nairobi, Triennale di Milano. Photo: Filippo Romano and Francesco Giusti.