7 February 2014

If you’re going to interview that undisputed master of contemporary design Enzo Mari, you need to bear at least two things in mind. The first is that chatting for an hour or so won’t be enough. Mari gets carried away, tells stories, strays from the topic: it’s going to take two, three hours, but perhaps not even a week would be sufficient. The second is that he asks the questions. And then comes up with lengthy answers to them, which give the cue for a few timid questions on the part of the interviewer too. Born near Novara in 1932, Mari has been the mind and hand behind many designs and objects that are simply brilliant: Il gioco delle favole (“Fable Game”) for Corraini and the 16 animali (“Sixteen Animals”) for Danese, the Day-Night couch and Delfina chair for Driade, the Tonietta for Zanotta, the Aggregato lighting system for Artemide, the Titanic juicer for Alessi. To mention just a few. But along with the works, there are the ideas: Alessandro Mendini has called Mari the conscience of design. Designer, critic and theorist, he has won the Compasso d’Oro four times (including one for Lifetime Achievement in 2011), has been included in the elite list of Royal Designers for Industry by the Royal Society of Arts in London and has been awarded an honorary degree in Industrial Design by Milan Polytechnic. He has taught at a number of schools of design and architecture, taken part in exhibitions all over the world, from the Louvre to the MoMA, and written several books. The most recent, published in 2011 by Mondadori, is the autobiographical 25 modi per piantare un chiodo (“25 Ways to Drive a Nail”), edited by Barbara Casavecchia. A few months ago he closed his studio in Milan and has “no intention of thinking about new projects.”

16 animali, design by Enzo Mari for Danese Milano, 1957.

We can start. I think that to conduct a proper interview I’d have to stay here, in your home, for at least a week.

Let’s try instead to deal with a few questions in the time available to us. Would you like me to reveal a secret straightaway? I realize it’s a suicidal thing to say, but I’m going to do it anyway: I’m a communist.

Really? Isn’t that a bit much to start with?

Let’s be clear, I’ve never been a member of the party. Partly because whenever I set out my ideas and tried to make contact with someone, I always got the same answer: you’re a good guy, but these are things that’ll be talked about in forty thousand years. The whole of communist culture was based on two words: structure and superstructure. They were the linchpins of Marx’s work, ownership and production. In other words, the possession of power: first Lenin and then Stalin.

Does communism still exist?

No. The current representatives of the PD [Democratic Party, heirs of the Italian Communist Party] are totally ignorant. And it’s not at all clear what its new secretary Matteo Renzi is driving at. And then there’s Berlusconi, who’s very clever, but has a brain from which the ethical compartment is completely missing. The fact that communism no longer exists is not just a problem for Berlusconi, but for the PD too, a party in which everyone is chasing a different illusion.

The question comes naturally, especially in view of your definition of design as “democratic utopia.” Is design political, should it be concerned with public affairs?

It’s a good question, and one which we all find easy to say yes to. As far as I’m concerned, ever since the years immediately after the war and then the fifties, when the first troubling rumors about Russia were already going around, one thing has always been clear to me: Marx never thought that the revolution was going to happen in Russia. He was thinking of France, Germany or the United States. Because the revolution ought to take place where capital, that is wealth, is being produced.

And so in today’s China too?

I’m not able to get a clear idea of what is going on in China, even though twenty years ago I had a great desire to go there. That said, I doubt whether the country is really being run by a communist party.

Timor, design by Enzo Mari for Danese Milano, 1967.

Yes, but in China today two fundamental factors are lacking: order and freedom.

You know, in 1989, at the time of the protests in Tiananmen Square and the massacre of students, I reflected on this with the small amount of information available to me: from a certain point of view, at a time when China was coming under the sway of capital, I thought that it was a legitimate reaction. What does it mean letting the young have their say? It’s like during the Salone del Mobile, when everyone is showing off their little things. In cases of that kind, freedom ought to be suppressed.

Would you work with the Chinese?

I don’t bother my head about things like that: the motivations of design should prevail under any conditions, whether it’s in Italy, China or Ghana.

You have a reputation for being surly and you’ve even been called the Savonarola of design. Judging by the way you look, though, you seem to be an optimist. Projects for the future?

I used to be profoundly optimistic, but now I find myself in deep difficulty. I’ve closed my studio on Piazzale Baracca, in Milan, and at the moment I have no intention of thinking about new projects. I’ve devoted sixty years of my life to reflecting and designing and now I’m full of aches and pains. And yet, even if Merlin the wizard were to come by and get rid of them all by magic, my only desire would be to go away.

What is the real secret you guard, that no one has understood yet?

That Italian design was not invented by the designers of Milan, but the craftsmen of the South who then lost their jobs as a result of urban migration and the spread of technology. The craftsmen produced essential objects for people working the land. For example, they would make a bucket out of a sheet of metal. The problem is that that bucket wasn’t called design, but was seen as the fruit of handicraft.

Is there a need which no one has met yet?

Lots of them. Let’s start by saying that I saw the birth of design: in Milan I was the youngest, and the people who were older than me—Marco Zanuso, Ettore Sottsass, Achille Castiglioni, Franco Albini—said that I was a promising young man. I’ve been good, but I failed to attain my utopian goals. Apart from discovering, at the age of forty, that when I was eighteen and twenty I’d been a little genius. But I gave it my all.

Tonietta, design by Enzo Mari for Zanotta, 1985.

What would you like to say to the young today?

We were all very poor in my family, and I didn’t go to any school. First of all it would be necessary to explain to the young what industry is, and to remind them that design is not an industry, but an activity for small entrepreneurs. Industry and design only went hand-in-hand with Adriano Olivetti, who was an exception, and not just in Italy. As for the others, even the ones who invented the Vespa for example, they were not designers but small-scale entrepreneurs who produced a useful object at a time when everyone went around on foot.

What would you invent today?

Let me make a basic statement. Industry was born in the middle of the 18th century when 28 million people lived in France. If you eliminate the rich, that means there were 27 million poor. When the word égalité was pronounced for the first time, people wept with happiness and wonder. But after the initial enthusiasm they started to need shoes, underpants and all the rest. It was then that they understood what equality really means, and it was then, at that moment, that industrial production was born. The handcrafted object, made in Versailles, was simply too costly.

What is the real mechanism of industry?

Industry relies on the low cost of labor, and the price of a product being established precisely. Let’s say that it takes two euros to make an object. To set the price, the owner of the factory decides to multiply those two euros. In the case of design, the multiplier is a factor of five or six, so that two euros become twelve. For the luxury end of design, which is the only segment of the market that is still healthy, that multiplier can be as much as eight or twelve.

So what does the designer have to do?

The designer has to understand the mechanism of industry, which requires a worker to cost as little as possible. It all started when the first assembly line was created. Thinking is prohibited on the assembly line. Workers agonize because they are no longer able to think, they can no longer use their brain. If I was a government minister I’d close the vocational schools and tell everyone that they have to do it on their own. A few small industries would understand, but not the workers and the unions.

No workers.

If I were in good health and had the determination I used to have, I’d say that workers should be eliminated. Not that I’d send them to jail, but we need to get rid of the figure of the wage earner, who is worse off than the slave in ancient Rome. When I say let’s eliminate workers, I’m not saying we should invent robots to replace them. The worker ought to earn his living in a different way, he should be getting a percentage, even a small one, of the proceeds of his labor. He’d no longer get paid a wage, but after fifteen years he would become a partner in the company. The last people to understand an argument of this kind would be the workers, who still believe that their salary is the solution to all the problems.

Titanic, design by Enzo Mari for Alessi, 2000.

But what are the difficulties faced by industry today?

We, and I mean those of us in the US, Europe, Japan and a few other small countries, live in the well-off part of the world. It is the West that invented modern culture, scientific knowledge, manufacturing, engines, capital and the exploitation of capital. And it has produced affluence. An affluence that stems from five centuries of plunder of the planet. Without capital, there would be no schools, hospitals and many other important things. The West has developed around this ambivalence: plunder and wellbeing of the population.

And the other part of the world?

Bear in mind that a Third World country, in the course of a generation, is acquiring all the economic capacity of the West, and this is going to make things worse and worse. The real crisis will come when people start shooting in the streets, for the Fourth World will acquire our technological capacities. China, even though today it prefers to speculate with real estate, that is capital, would be able to produce all the manufactured articles of the West in the space of a year, if it wanted to.

You see no way out, it seems.

In Italy we could react with reforms, with laws, but it’s too difficult: how can you make laws with Grillo? Passing laws means changing things radically, but ordinary people would not understand and would fall back into the arms of those who say “no taxes on the family home.”

Let’s talk about design.

Design is not an industry. I’d throw out all those who teach design in schools, because what they pass on are interpretations, theories and points of view. It’s necessary to understand things in a concrete way, based on experience. If I go to a field of tomatoes I don’t rely on an interpretation: I know that they’re tomatoes. If I don’t know, I taste one and find out. People know what a tomato is, but they don’t know what design is. Do you want me to tell you how you mold the mentality of sixty million Italians, or if you prefer seven and a half billion human beings?

Please do.

When someone is young and hasn’t been to university yet, he starts to dream about a certain kind of activity. Often he allows himself to be influenced by his friends and by the girl he likes. He begins to think vaguely about an identity. In exceptional cases he has an important family behind him, or the luck to be able to talk to someone older who knows what’s what. Otherwise, he observes his peers and focuses on the ones who give him the impression of having a bit more drive. He uses them as a reference, to form an opinion. The problem is that on these bases he then makes a definitive choice.

Mariolina, design by Enzo Mari for Magis, 2002.

He follows a model.

In the countryside horses and donkeys go around with pieces of leather placed on either side of the eyes to make sure they always go straight ahead and are not distracted. But such an attitude kills the brain, even though the brain is very powerful and has the sole defect of aging as time passes. When a child is born it has billions of neurons connected to each other, and in fact children are very intelligent. It’s something I often say: they ought to give the Nobel Prize to a two-year-old.

How do you take blinkers off?

You have to make choices. There are tens of millions of Italians who avoid choosing. We have to think about the quality of life. The quality of life lies in discovering, in trying to do one thing and discovering something else. I’ve devoted my life to removing people’s blinkers, but I’ve failed miserably.

What can still be done?

Today it’s necessary to tell people how industry functions, because industry needs ignoramuses who don’t waste time thinking. As for design, it’s a requirement for those who want to surround themselves with things that seem beautiful, but often they are not. I feel like saying: that’s enough, get a life, damn it! Close down the schools of design and get back in contact with reality. After all, it’s real life that matters.

Apropos of real life, why are there so few women designers?

First of all, there is the weight of history. In the past, only women in wealthy families had an identity. In poor families, the woman was just another worker who did all kinds of jobs, and then everything else as well. The woman is a designer blessed by God. Because she designs, realizes and, finally, constructs other human beings. The male is more robust, and this has its importance. But the woman’s deepest concern is her own making of human beings, and it’s a profound characteristic, even in women in their 40s, 50s, 60s. You know who used to be the ideal life partner for a woman?

Who?

A fat man, because it meant that he had money and enough to eat. Women used to say: “I prefer someone with money who can support me and my children.”

What do you think of the women of today?

If I look at women, especially young women, I have more faith. They have more determination, are more willing to change, because they are occupying new spaces in life. Whereas men are freaking out, they no longer have points of reference. They have lost their passion and their madness.

What is your relationship with Lea Vergine, your life partner and a famous art critic, with whom you were accused of concubinage in the sixties?

We’ve been quarreling for fifty years. I was married before, I’ve had girlfriends. I met Lea by chance, in Naples, after I’d asked Giulio Carlo Argan to suggest someone who could take care of the graphics of a magazine. So I went to Naples, to a hotel, which I entered around midday. I could see no one in the great hall. Then at the back of the hall I saw a man and her. She was 26 at the time. I stood there like an idiot. Lea was a beautiful girl, but I was too shy and thought about beautiful girls in vaguely mythological terms. For me they were a sort of gift of the gods that arrived from heaven. If God thought that you deserved it, he gave you this chance to meet the woman of your life.

Love is a project?

No, it’s much simpler than that. Standing there like an idiot, at the back of the hall, with her looking at me, taking two or three steps toward her. And her taking two or three steps toward me. Perhaps love is taking two or three steps in the same direction.

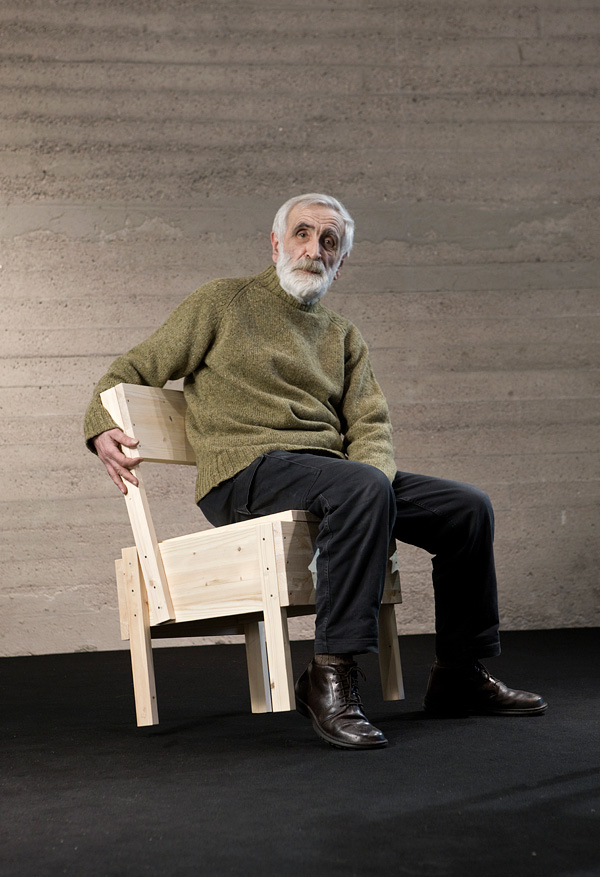

Enzo Mari, 2012. Sedia 1 Chair, design by Enzo Mari for Artek, 1974.

Formosa, design by Enzo Mari for Danese Milano, 1963.

Sei Simboli Sinsemantici: Undici, Cubo, design by Enzo Mari for Danese Milano, 1972.

Globo, design by Enzo Mari for Magis, 2001.

Aggregato, design by Enzo Mari for Artemide, 1976.

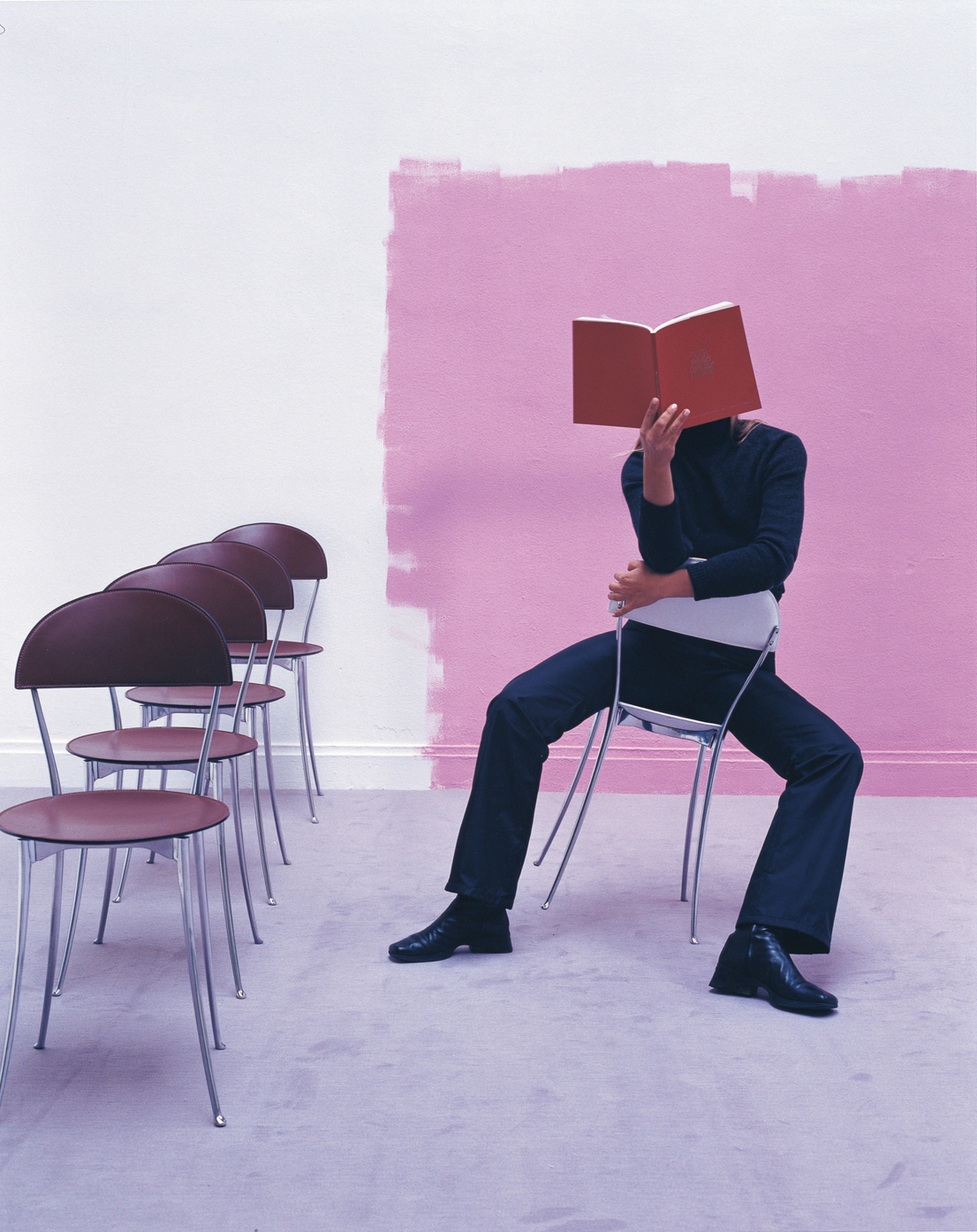

Delfina, design by Enzo Mari for Driade, 1979.