21 March 2014

Yuri Ancarani is not an artist who directs the scene or gives instructions on how his characters should behave. He is a simple man who observes, records, learns. He uses the camera lens to look for pieces of authentic reality, not touched by the frills that turn real life into fiction and people into copies of TV personalities. Ancarani goes beyond the boundaries of video art to produce short films that blend documentary cinema and contemporary art. In his research he sets out to explore regions of daily life that are not very visible, situations into which he ventures in person in order to cross unexplored thresholds, to enter territories that are often risky but so stimulating that they constitute a personal and professional challenge. His latest project is a trilogy—Il Capo (“The Foreman,” 2010), Piattaforma Luna (“Luna Platform,” 2011) and Da Vinci (2012)—devoted to the theme of work, or rather to those extreme, unusual and little discussed occupations that are carried out in fascinating and difficult settings, on the edge of survival. The three films have been shown at prestigious international festivals like the Cinema Eye Honors at the Museum of the Moving Image in New York, the Rotterdam International Film Festival and the Venice Film Festival. In 2014 Ancarani was one of the finalists for the MAXXI Prize. His first solo exhibition is currently underway at the Isabella Bortolozzi Galerie in Berlin and will last until April 5: La Malattia del Ferro / Die Krankheit des Eisens [‘The Disease of Iron’].

Yuri Ancarani, Il Capo, 2010. Courtesy: Yuri Ancarani and Galleria Zero.

You were born in Ravenna, and after finishing high school moved to Milan to study at the NABA, where you graduated under the supervision of Paolo Rosa. Was it there that you started to devote yourself to the video?

In the nineties the NABA was very small, but some big names were already teaching there: the president was Gianni Colombo, Hidetoshi Nagasawa taught the course of sculpture, while among the professors of art history there was Vittorio Fagone, who focused on land art and video art and took us to see exhibitions by artists like Robert Cahen or Gary Hill. For me, who had received a traditional education, it was a completely new world. The NABA also had a very well-equipped video workshop where I spent a lot of time learning the techniques of editing. The professor in charge of the workshop saw how interested I was and gave me the keys so that I could go in at night to work on my projects. All this to say that, yes, my first contact with the video took place right there.

You left Ravenna in 1991, but this city, the Riviera Romagnola and Rimini are places that crop up continually in your works. What do they represent for you?

In Milan I really missed Romagna, it was all so new to me. I remember that as soon as I arrived I called my mother to tell her that in Milan there were trains in the streets! I was eighteen, but I’d never seen a streetcar in my life. I realized that it was important to experience the big city, but at the same time I found it rather cold, distant: a perfect showcase to present my works, but I had to make them elsewhere.

And so you went back to Romagna often?

Yes, I was interested in telling the stories of a little world that I knew very well. In Romagna there is a great cultural vivacity, everyone has a bit of the artist in them and people set about doing whatever is their thing with a special passion. There is a lot of craziness and craziness is always useful. At the beginning of my career, when my budget was equivalent to zero and I still needed a great deal of practice to acquire the right technique, I always found the situation ideal in Romagna: lots of help and no one backing out.

Yuri Ancarani, La questione romagnola, 2002-2012. Courtesy: Yuri Ancarani and Galleria Zero.

The critics define you by turns as a video artist or a filmmaker. Your videos are shown in art galleries and presented at film festivals. Do you feel at ease with this union and dualism of art and cinema?

In 1995-96 I took part in the Video Art Festival in Locarno, an event that no longer exists today and that principally showed videos of the eighties and nineties. It was an important experience, and led me to mix up the world of cinema and that of video art. Today this seems natural, but just a few years ago it was not like that: making a film was very costly and took a long time, while a video was produced quickly, often at the expense of visual quality. They were two very different worlds, while today the overlap between art and cinema is very great, even from the technical point of view: you can use the same equipment to make videos, photos and films.

What does practicing art mean for you?

The world of contemporary art is a sort of refuge for the most disparate talents. At the outset of my career, I found myself in joint exhibitions with actors doing performances, architects developing projects of social urban planning, photographers of every kind, professionals using the blank container to carry out research. Well, that’s what I felt like: a professional using the blank container to carry out research. Contemporary society is centered on business, but the art world still offers this possibility. Today more than ever it is the task of the artist to get you to open your eyes and look at reality sideways.

How do you make your works? Do you have a team working for you?

I work with a mini-crew made up of five people. I don’t feel like a director because I don’t direct anyone: the director works with actors, while my actors are real people who I leave free to act in a natural way. I start making my film with great humility and put myself on the same level as the person I’m working with: a workman, a technician or whoever. Then, as the project gradually takes shape, I start to talk about myself and what I’m doing. Until I arrive at the presentation of the film, when I explain that we have worked together on the creation of a work of art.

In your stories it is as if at a certain point a shift takes place from a simple account to a hidden, invisible side of the events. How are your films born?

I start out from stories told me by friends, by people I meet in the street, at the bar. Often they are strange stories, about little-known things. The stories become intuitions and the intuitions in turn make me imagine situations. I rely a great deal on my relationship with people, on what I discover by observing them. My method is based on images, and when you hear voices it is because they are significant as a source of information, as in Piattaforma Luna, where the characters have the nasal tone of voice that comes from breathing helium, which it was important to hear. It is hard to work like this, but I have imposed very strict rules on myself, I move within a veritable cage of rules. The fact is that as soon as you start to make the account explicit you get caught up in the mechanism of TV and the viewer becomes passive, whereas what interests me is that the viewer has a real experience and thinks about what he is seeing to the point where he “takes the work home” with him.

Yuri Ancarani, Piattaforma Luna, 2011. Courtesy: Yuri Ancarani and Galleria Zero.

In the collection Ricordi per moderni (“Memories for Moderns”), which presents fourteen videos made between 2000 and 2009, you speak of industrial zones, vacation spots, airplanes, sex, children, gambling, money. You try to reveal the hidden side of each aspect, to show what is known, but often not visible. Can you talk to us about this production?

The beauty of Ricordi per moderni is that there is fiction, there is performance, there is reality, and at a certain point it is no longer clear what is true and what is false. They are stories that come from my own experience, or from what I have seen or been told, or something that I have just imagined. They are videos that I made separately, but when I united them in a single collection I saw that together they had a life of their own. The occasion was provided by an exhibition at the Museo Marino Marini in Florence in 2012, where I created an installation with fourteen videos projected in three sequences on a set of four screens hung side by side. A fifteen-meter-long bench in front of the screens allowed people to have a vision of the whole thing and at the same time to watch each video individually.

Why this evocative title, Memories for Moderns?

The title is inspired by one of Pier Vittorio Tondelli’s writings. It seemed perfect for this collection of works.

You’re very attached to Tondelli, an Emilian writer who died very young, the author of novels like Rimini (1985) and Un weekend postmoderno. Cronache dagli anni Ottanta (1990). What does he represent for you?

After seeing my video Vicino al cuore (“Close to the Heart”), Tondelli’s trustee, Fulvio Panzeri, asked me to take photos for a publication to mark the tenth anniversary of his death. From that moment on, I started to read Tondelli’s books. He had also written about Lido Adriano, its architecture and the scenery of the Romagna coast, and so, following the suggestion of his writings, I began to photograph this beach resort, which in the meantime had become Ravenna’s ghetto for immigrants. The video that came out of these photographic works was made on a zero budget, so the nighttime shooting was illuminated with the headlights of my car, which I lowered or raised in a mechanical way: by driving the front wheels up or down on small platforms.

Yuri Ancarani, Ricordi per moderni, 2000-2009. Museo Marino Marini, 2012. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

In what way was the video related to the photos that you’d already taken?

The focus started out from the framing of the photos inspired by Tondelli’s text, and then widened out to reveal the new inhabitants of that strange resort. While my friends prepared the dolly and the shot, identical to the photo, I went around at night looking for the protagonists of the video. I found groups of people and asked them to come and do what they were doing in front of the camera. Then, without disturbing them, I let them move around, do things, talk. Obviously they were all speaking incomprehensible languages that have deliberately not been translated in the video.

In terms of shooting technique and content, what has changed between your early works and the more recent ones? Has your interpretation of reality remained the same?

My interpretation has always been based on the desire to go beyond. Now, for example, for the first time in my life I’m scouting locations abroad. Apart from this, my work has changed a lot from the viewpoint of technique: the early videos were all made on a zero budget, an experience that was necessary for me to understand many things and learn to make mistakes and correct them. But working on a zero budget is like a game, where you can do anything and its opposite. Now I work with film studios and can no longer allow myself to make mistakes: you have more quality, but less time.

Another very interesting work of yours is In God We Trust of 2008, which tackles a range of highly topical subjects: money, the relations between different cultures, the integration of peoples. What prompted you to focus on money and the Nigerian community?

Curiosity. When I went back to Milan after spending the weekend in Ravenna, I saw lots of handbills in English around the station advertising Nigerian parties. So I started to ask people for information, but no one would tell me anything, until I met the head of the Nigerian community in Ravenna and told him that I wanted to film these parties. He agreed and so I found myself at a party that ended with money being thrown in people’s faces. It’s a tradition, a sort of ritual: in the same way as we might make a contribution to the expenses of a party, they throw money in the organizer’s faces to recompense them for their efforts. They use dollar bills because they are a symbol and because to some extent they feel themselves to be Afro-Americans, but that simple gesture, which is not at all mysterious for them, is charged with all sorts of meanings for us.

Yuri Ancarani, In God We Trust, 2008. Courtesy: Yuri Ancarani and Galleria Zero.

The trilogy formed by Il Capo (2010), Piattaforma Luna (2011) and Da Vinci(2012) investigates the relations between man and machine. What attracted you to the world of work?

Just as for the other videos, the idea for these three films came from real stories, told me by people I met. For Il Capo, it was a photographer friend of mine who told me about a marble quarry that was really worth visiting. For Piattaforma Luna, the stories of divers overheard in a bar near the port of Ravenna were decisive. As for Da Vinci, the idea came to me both from conversations with a friend who is a biomedical engineer and from thinking about my mother’s work as a nurse.

In Il Capo you present the work that goes on at a quarry in the Apuan Alps. How long did it take you to make it and under what conditions?

I spent a year shooting everything that went on in the quarry, and then carried out a long work of selection in postproduction. Out of everything that I had seen and filmed, I thought the most interesting moment was the one in which the quarry foreman directed the cutting away of the blocks of marble. Then I did a work of synthesis around this scene.

Piattaforma Luna recounts the experience of six divers on the Luna A platform, in the Ionian Sea, which works on the extraction of natural gas under extreme conditions because of the high pressure underwater and the atmosphere filled with helium. How were you able to shoot these scenes?

The length of time I worked on Piattaforma Luna was very different from Il Capo, for obvious reasons connected with permits and the material conditions in which the filming was done. I shot it all in seven days: three days of filming in the hyperbaric chamber and four outside it. It was a tough, difficult experience, you can’t perform miracles in three days. And in the end I understood that the platform is a really dangerous place.

How important was Maurizio Cattelan’s involvement in the production of the video?

Maurizio played a fundamental part. I was still working alone, without producers. I was collaborating with him on something for the magazine Toilet Paper and had got to know him better. I told him about all the difficulties I was encountering in making Piattaforma Luna, with permits: I had finally been given permission to go to the platform, but without being allowed to enter the hyperbaric chamber where the filming would have to be done by a specialized operator. Maurizio did not agree with this at all, and offered to produce the work on condition that I was the one who went into the hyperbaric chamber to do the filming. I accepted the challenge, and insisted until I was granted permission to spend three days inside the chamber. Maurizio kept his word and we coproduced the film. In the end I realized the value of his advice, not so much from the economic viewpoint as from the fact that he made me understand that my film had to be shot by me and no one else.

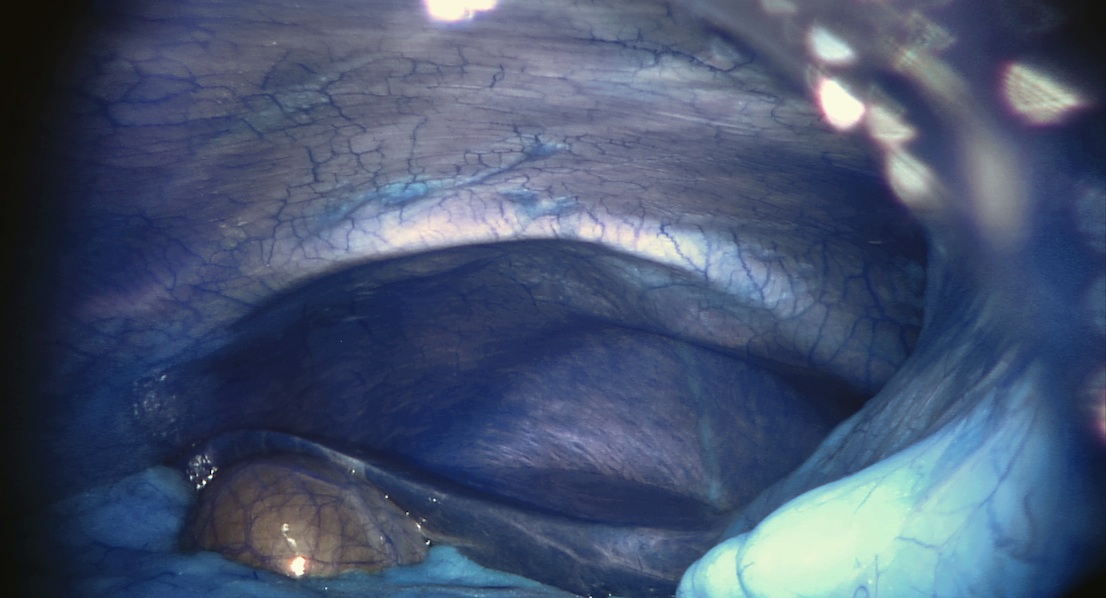

In Da Vinci you film an operation of robotically-assisted surgery in which the protagonist is a surgeon working on a real patient. What was that like as an experience?

My executive producer Alberto Salvadori and I had contacted hospitals in Milan, Naples and Florence: at the beginning no one was willing to authorize the shooting, until we got a positive response from the department of robotic surgery at the Cisanello hospital in Pisa, a structure connected with the university where the surgeons were used to having groups of students in the operating room. So I was able to start the shooting by blending into the students, and gradually I got to know the procedures of the hospital so that I was able to move around like the medical staff: I dressed like them and went into the operating room knowing when I could ask questions, when it was better to keep silent or when to get out because the situation was becoming delicate.

Yuri Ancarani, Da Vinci, 2012. Courtesy: Yuri Ancarani and Galleria Zero.

A challenging experience.

I spent a month filming in the hospital. Obviously, at the beginning the impact was traumatic. The first open-heart operation that I witnessed was really shocking. Then I grew accustomed to some extent and was able to attend the operations without becoming emotionally involved. The problems emerged in postproduction, when I was severely criticized by my assistants after they saw the crudest scenes and got me to ask myself some questions: what did I want to achieve? Was it right for people to see certain things? And if it was right, how could I show these things to them? In the end I decided to cut the most disturbing moments, so as not put the true content of the work at risk.

Your trilogy turns ordinary people into “mythic men,” heroes to be remembered. Who for you is the hero in today’s world?

I’d say that in the trilogy heroes are present chiefly in Il Capo and Piattaforma Luna, while in Da Vinci it is the machine that prevails, overshadowing the human being and coming out on top. Apart from this, the theme of the hero is a very important one. These days we live in a work of fiction where a bogus vision of the hero predominates, something that is conveyed in particular by television. Instead we ought to be talking about the people who do their jobs, often dangerous ones, every day with passion. Some know that they are risking their lives, but don’t want to change, and for this reason too are real heroes. The interesting thing, though, is that these “mythic” figures often have figures from TV dramas as their own heroes. The divers in Piattaforma Luna, for example, are clones of Fabrizio Corona [an Italian TV personality currently serving a jail sentence for blackmail; translator’s note]: he is a continual source of inspiration for them. Or at least he was: when they saw themselves in my film, they realized the unique value of their own personalities.

Yuri Ancarani, Da Vinci, 2012. Courtesy: Yuri Ancarani and Galleria Zero.

Yuri Ancarani, Rimini, 2009. Courtesy: Yuri Ancarani and Galleria Zero.

Isole di acciaio, Isole d’acciaio, 2005. Courtesy: Yuri Ancarani and Galleria Zero.

Yuri Ancarani, Ip Op, 2003. Courtesy: Yuri Ancarani and Galleria Zero.

Yuri Ancarani, Il Capo, 2010. Courtesy: Yuri Ancarani and Galleria Zero.

Yuri Ancarani, Da Vinci, 2012. Courtesy: Yuri Ancarani and Galleria Zero.