5 November 2014

William Kentridge is one of the most significant artists of our time. And yet, at first glance, his works seem to hark back to a distant past, when being an artist meant using a manual skill that since the 1960s has slipped into the background, or vanished completely. Since that time it is the concept that has ruled the roost in the contemporary art system: an abstraction of thought that is often reflected in the work in a didactic manner, or through abstruse processes of interpretation. Kentridge, instead, marries form and concept: with charcoal and collage he brings into question the fluidity of current imagery; with smudges and deletions he reveals the instability of thought and of the values underpinning history; and with his theatrical mimicry involves us, as actors and spectators. His work is rooted in a Modernism that extends well beyond the cultural and spatiotemporal framework in which we are accustomed to set it: not the 20th century, not the West. Being modern is a state of mind, it is understanding the world to be fragmented, it is speaking of colonialism and power, of emancipation and desire.

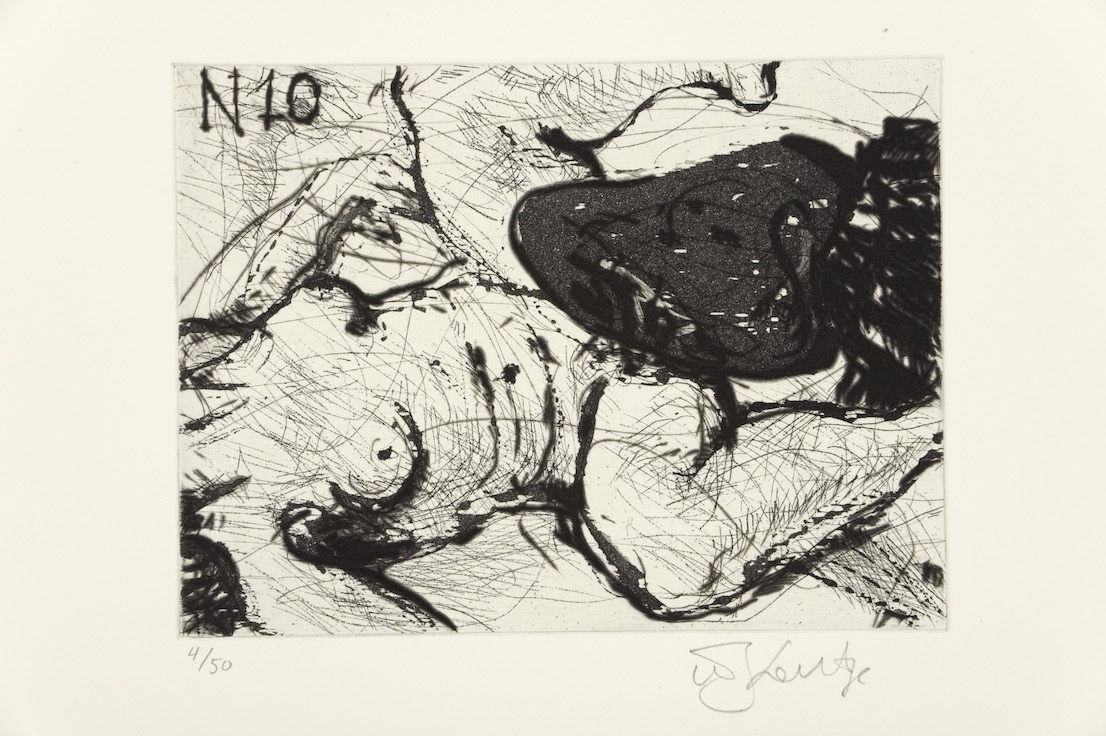

William Kentridge, Nose 10, 2008. Photo: John Hodgkiss. Courtesy: William Kentridge and Lia Rumma Gallery (Naples and Milan).

Your art has travelled to the world’s most famous museums. You, instead, have never left Johannesburg. What is this special bond you have with the place?

After fifty-nine years I am still in the same town. There obviously has to be a strong connection, I am not sure what it is. It’s a love and hate relationship. Very often I think it is insane: I am like a medieval peasant who never leaves his house. I am not showing people Johannesburg and there are no local references in my work. But Johannesburg gives a very clear context to it. So even if I’m speaking about Russia, as when I staged Dmitri Shostakovich’s The Nose, or I am looking at Alban Berg’s opera (Lulu is Kentridge’s latest production for the Metropolitan Opera House in New York, set to premiere in 2015, editor’s note), everything I do is filtered, contaminated by the city.

Your father, a lawyer, was deeply involved in defense of the weaker and marginalized groups in society under Apartheid, and critics have often seen this biographical motif in your work as a personal commentary on Africa’s social and political history. Do you agree with this interpretation?

My work is not political per se: it’s very much based on what happens in my studio. And there is a lot of politics that goes around and into the studio, and so it gets into the art. If we say a work is political, we have to say there is a political program, and there is no political program in my art. It responds to society and the politics around it. And I am sure that it is natural for a child growing up with parents who are lawyers to be influenced by this. But there is also a reaction to it. The work allows itself an openness which is kind of impossible in the realm of law. It’s a reaction against law.

Once you said that your art is not so much ideological as therapeutic: it relates to the treatment of illness. What did you mean?

It’s not ideological in the sense that there is no clear political description of the world that the work is seeking to illustrate. My work results in a resistance to claims of certainty, which also lay claim to authority, justifying violence.

Certainty is injected into our lives by politics and advertising campaigns through vivid imagery and catchy statements about what we want and who we are. You, instead, speak about the complexity of the real by avoiding the shortcuts, the appealing. Also, most of your work covers the spectrum between black and white. It deliberately shows imperfections and corrections, the images are fragmented. Is it based on an explicit renunciation of the formal possibilities of artistic experience?

When I started color was a rare luxury. If you wanted to use a bright blue, you had to crush lapis-lazuli, a semi-precious stone, just to get that blue color. If you wanted to have brilliant color, you would use it only in the smallest part of the painting, to show how it would look to the clients. Whereas now bright colors are kind of taken for granted. So it’s partly a resistance to that bright color, which is now the terrain of advertising. But it also has to do with sensibility. When I am working with charcoal, it’s a way of thinking; but when I am working with color I am making something pretty. It’s a terrible question for an artist to ask himself whether a work of art looks good or not.

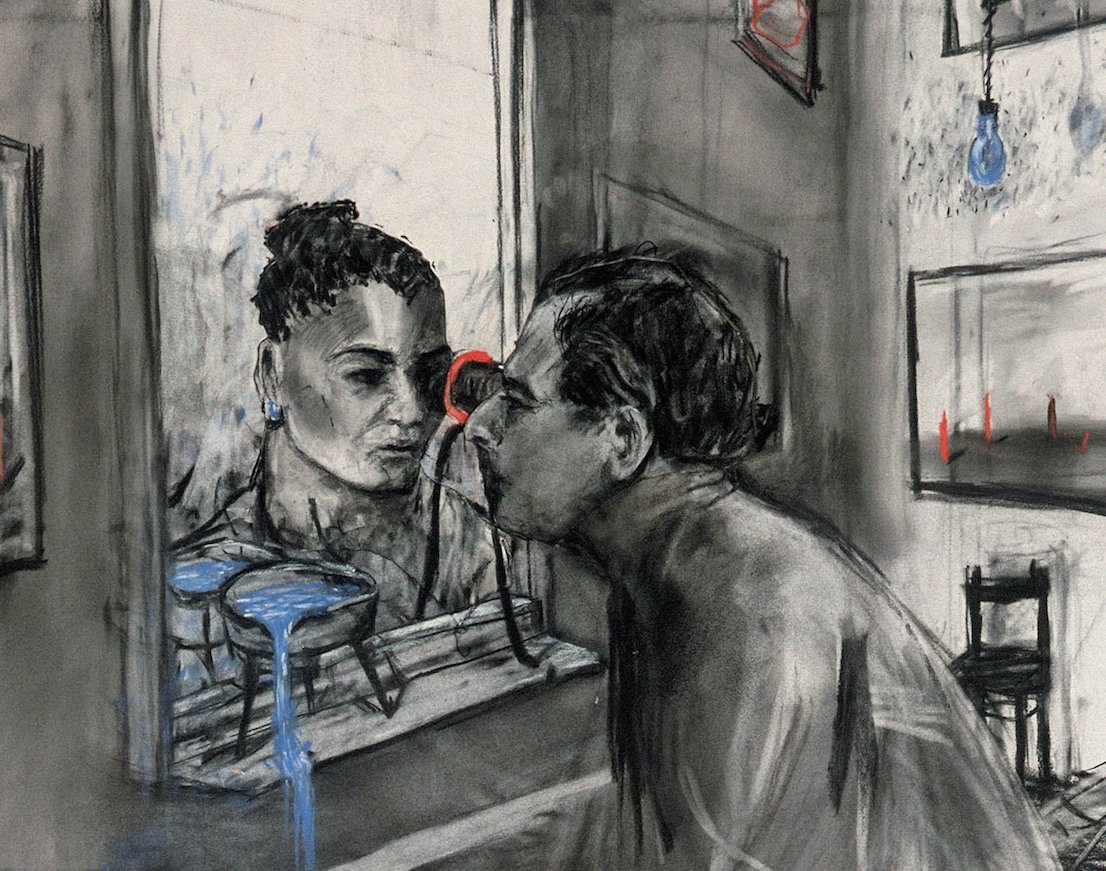

William Kentridge, Felix in Exile, 1994. Courtesy: William Kentridge and Lia Rumma Gallery (Naples and Milan).

Since you deliberately decided to become an artist, you have tried your hand at many media, from film to drawing, sculpture, theater and opera. Though everything stems from drawing, which is normally seen as an ancillary, secondary medium when compared to painting, the historically most compelling and luxurious form of art. What does drawing represent for you?

We are in Palazzo Tornabuoni in Florence, at the heart of that debate between colore and disegno: the battle between Venice and Florence, with Michelangelo thinking that no one taught Titian how to draw and Titian thinking that Michelangelo knew nothing about color. It’s all about the ways in which someone thinks about the world. Some people structure the world through ideas in color, and they work as painters. While I think the world in charcoal, almost as if the charcoal were some kind of writing.

You have described your latest production, a live cine-concert entitled Paper Music that was recently premiered at the festival “Firenze Suona Contemporanea,” as a reflection on the way “sound can be seen and images can be heard”: a synesthetic experience where every element contributes to the processes of constructing meaning. What has been the reaction so far?

I’ll give you an example: in one of the films set to music there is a panther walking in chains. It’s a loop of three minutes. The music and the text start very slowly, then at a certain point they change gear and get much faster. Everyone, including myself who made it, feels that the panther does too, but in fact it does not. Your eyes believe what you hear; and if you stop listening to the song and look at the images, you become obsessed with the idea of a narrative. Even though there is just a panther walking from one side of the cage to the other three thousand times, you expect something to happen.

William Kentridge, Drawing for Other Faces, 2011. Photo: Thys Dullaart. Courtesy: William Kentridge, Lia Rumma Gallery (Naples and Milan), Marian Goodman Gallery (New York, Paris, London) and Goodman Gallery (Johannesburg, Cape Town).

In older works this illusory effect was achieved through the surrealistic transformation of objects, through mesmerizing metamorphoses, the representation of highly contradictory feelings and a powerful iconography made up of characters, such as the businessman Soho Eckstein and his counterpart, the artist Felix Teitlebaum (Soho and Felix, 1989-2003), or the corrupt despot Ubu (Ubu and the Procession, 1989-2002). What is your relationship with metaphor and fiction?

I think about reality through the physical space of the studio: a place where the world is invited in, and it enters very literally as newspaper cuttings of the war, drawings done the day before, notes for drawings still to happen, half-finished projects, phone calls, the internet sitting in the computer on the desk, a text from Herodotus stuck on the wall or a memory of a conversation you had. All these tiny fragments come into the studio, where they get cut up and rearranged. But there is also a piece of black paper on the table, a physical material: you tear that black paper. So it’s not so much a deep interrogation as to what is material, immaterial, real or fictional. It doesn’t matter that it’s a real photograph of refugees in Rwanda I am inspired by. Everything has equal status in the imagination, as well as in the imaginary space of the studio. Close your eyes and think of the studio as an enlargement of the head: your thoughts moving from one part of the brain to the other, a four-centimeter journey to a memory, to a current action, to a speech. If you enlarge this it becomes the walk across the studio. And the gallery becomes a further enlargement. What happens in the studio is not reality, but it’s half of what it is. It reflects the need we have to predict and to complete, to make sense. What an artist does is a demonstration of what we do all the time.

You are currently working on Alban Berg’s opera Lulu, scheduled to be staged at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York in 2015. What attracted you to it?

It was premiered around the same time as The Nose (1936), the opera based on the short story by Nikolai Gogol that I staged at the Met in New York in 2005, and it’s one of the masterpieces of the 20th century. Yet the music is hard to understand: I needed a long and close involvement with it to understand what Berg, the composer, was doing. The fact that I couldn’t make sense of it musically was then part of the attraction.

In fact Lulu remained incomplete at Berg’s death and for the next forty years. Arnold Schoenberg was asked to finish the work by his widow, but he refused.

I know, and that was a very good thing! Schoenberg would have been a very bad person to complete it: he was too good a composer, content with its own style, and he would have never followed Berg’s lead. Lulu would have been transformed.

What about the subject? It was very provocative at the time. Is it still so today?

Well the theme is interesting. You can read it as a sex case, a sex murder. But for me it’s specifically about the instability of desire: all men want Lulu to be in a certain way and for none of them she can be, so they all end up dead. She also wants to be in a certain way, but she can never meet her expectations. Thus she ends up dead too. It’s about the impossibility of satisfying desire in a bourgeois society. It’s a very cruel opera, written at a time, the mid-1930s, when outside in the streets there was a cruelty and nastiness that Berg reflects. Totalitarianisms were rising to power too.

I noticed that women, even when they are not the central figures around which the work develops, are a driving force in your visual imagery. Their presence alone, or a very simple action they carry out, can change the flow of the narrative. Does this stem from a specific intention?

I am not a novelist, someone who can put himself in the head of another person and construct a plot. That’s a kind of imaginative leap. I am not doing this in my films, where the perspective is always that of a white middle-aged South African man. I once tried to do a film where Soho Eckstein’s daughter was the protagonist, but it never got off the ground: I didn’t know what her thoughts could be. However there is some literal evidence of the presence of women: in Paper Music (2014) there are two women singers. I started to work with them for The Refusal of Time (2012), and there are so many women—performers, editors, producers, technicians, collaborators—who are involved in my works. And it’s not just that women are, as far as the content is concerned, objects of desire and love, even though they are certainly that as well, in terms of a middle-aged love which is not the traditional terrain of romantic love. I suppose in my films there is a banal representation of men’s desire, desire for women or desire for power or an intersection of the two. A childish and incessant “look at me, look at me!” Of course what is an artist doing if not spending his life saying “look at me?” So I understand the infantile that needs a feminist correction, to find a balance.

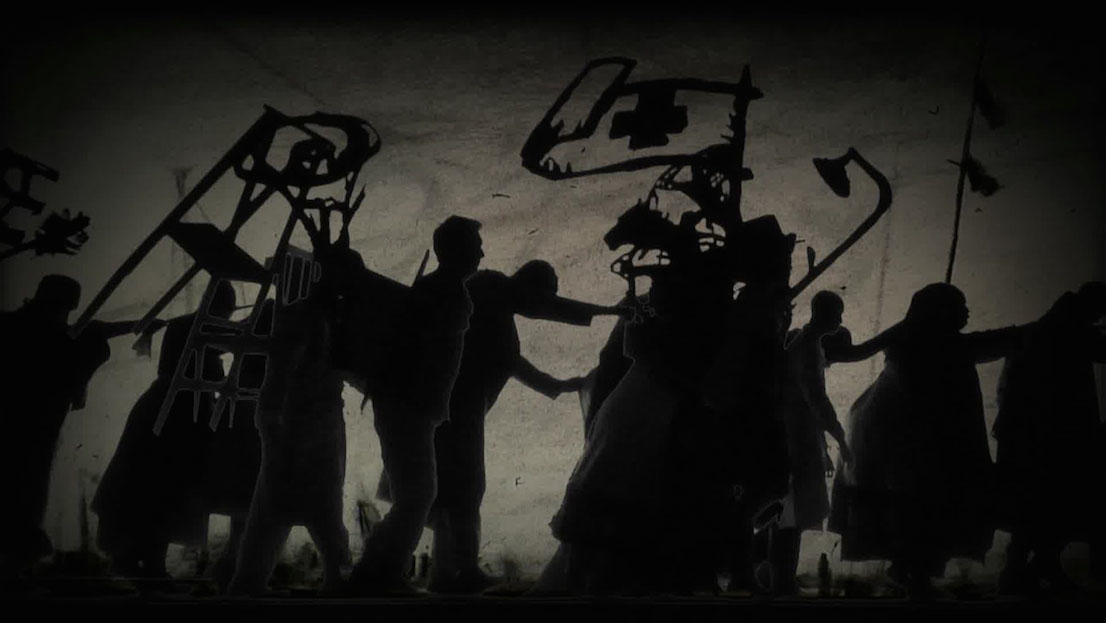

William Kentridge, The Refusal of Time, 2012. Courtesy: William Kentridge and Lia Rumma Gallery (Naples and Milan).

Do you find yourself thinking in grand categories like love, revolution, amnesia, history or truth?

I don’t. I am thinking much more in terms of: what kind of paper should I use and is there too much starch on the paper so that the ink doesn’t sit on it well? My work is the dissolution of the world into a thousand formal questions. And these big questions of history, philosophy and ethics come into the studio, and are taken apart into. Do I use this white paper, or this paper clip to join these two pieces of paper? Because you are focusing on the materials, the thoughts behind them have to look after themselves, and then reemerge once the figure is put together and starts walking across the page. When you finally see the film, it carries a certain input. So in the concert in Florence, for instance, some people told me they felt a strong emotional connection with what they experienced. I am pleased and astonished, because there was a whole series of bureaucratic decisions around the work, and it comes as a surprise that all these decisions come back as something that speaks for a rightness in the world, where music, image and performance come together. Still, there is a confidence, a pretension that in the end the work will show who you are. Everything in the end is a self-portrait, even if not drawn as a self-portrait. This is how I deal with these big questions.

Talking about self-portraits, you once said you feel fragmented as your tiny pieces of paper, and then you added that, absurd as it may seem, you find yourself in all your characters: the good ones and the evil ones. Who are you now?

I guess I am in between things! However, I have a fear that at a certain point I am going to turn into a rabbi: those people who speak with such certainty, you give them a topic and a portrait. I sometimes look at myself and I ask: “Oh my God am I giving a rabbi’s sermons?” Too many words, and my wife always reminds me to listen to the drawings.

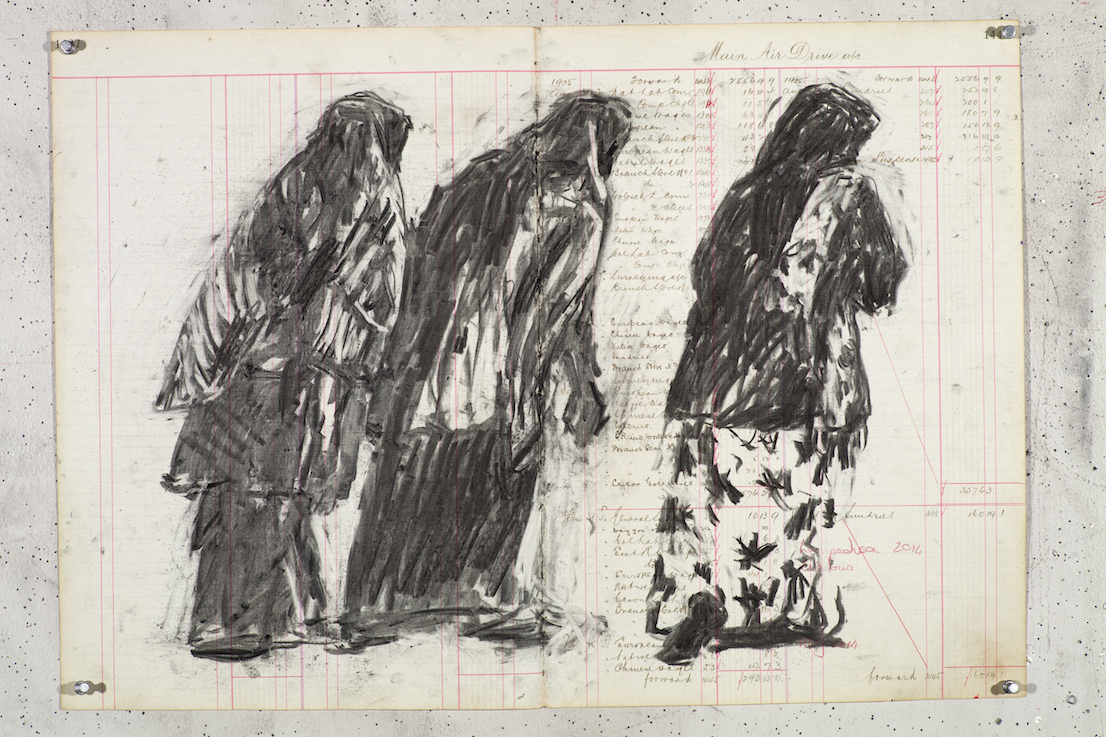

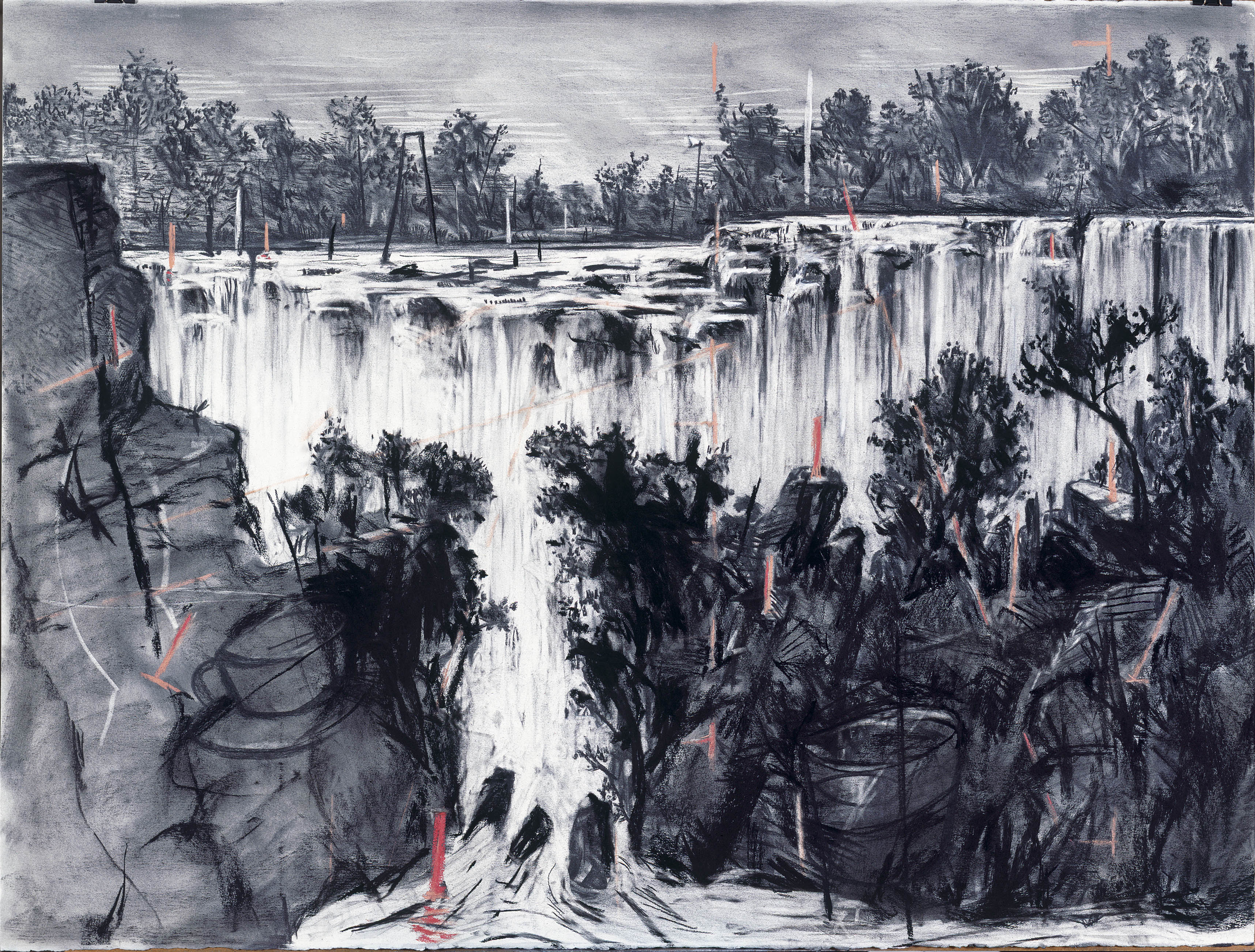

Before you go, I’d like to ask you about your work in progress, Triumphs and Laments (2015-16), which was conceived with the Tevereterno organization some years ago as an ephemeral public intervention in the city of Rome. Much has been said in the newspapers and magazines about the difficulties encountered in realizing it. What is it about and will it eventually see the light of day?

The project is a large-scale temporary frieze, five hundred meters long by nine meters high, on the urban waterfront of Rome. I am not removing anything from there, just cleaning some of the dirt on the walls to let a procession of human figures emerge. I have spent a lot of time doing preparative work, and I do not begin to understand the competitive nature of Italian cultural politics. If the people leading the project through this nest of vipers can reach the other end safely—namely the project happens and we get the permissions—Triumphs and Laments will see the light of day. If it isn’t unblocked by the end of the year, I will stop trying. We started talking about it long before my exhibition at the MAXXI in 2012. I have already drawn sixty out of the ninety figures and it’s not supposed to be a difficult project to produce: it can be done in a month, it’s easily manageable.

Who are the figures?

The work covers four thousand years of the history of Rome. So you have Remus lying dead on the ground having been killed by Romolo, the dead body of Pierpaolo Pasolini, the ecstasy of Saint Theresa, Marcello Mastroianni and Anita Ekberg in the Trevi Fountain from La Dolce Vita, a procession of widows of people who have drowned trying to reach Lampedusa, the abdication of Pope Gregory and Henry IV during the Sack of Rome in 1084. There are scenes from Trajan’s Column: as the actual frieze I have drawn inspiration from is damaged, it will look like the people are too. Then you have a group of people sailing in a boat: are they African asylum seekers or Romans seeking for shelter from the flood of the Tiber in 1939? The question is open.

You think the political content of this work might have been a problem?

The work shows all these images which are there in order to discover what politics really is. Somebody will find his or her triumphs, others their laments: it’s the ambiguity of history.

Thank you.

William Kentridge, Drawing for Triumphs & Laments, 2014. Photo: Thys Dullaart. Courtesy: William Kentridge and Lia Rumma Gallery (Naples and Milan).

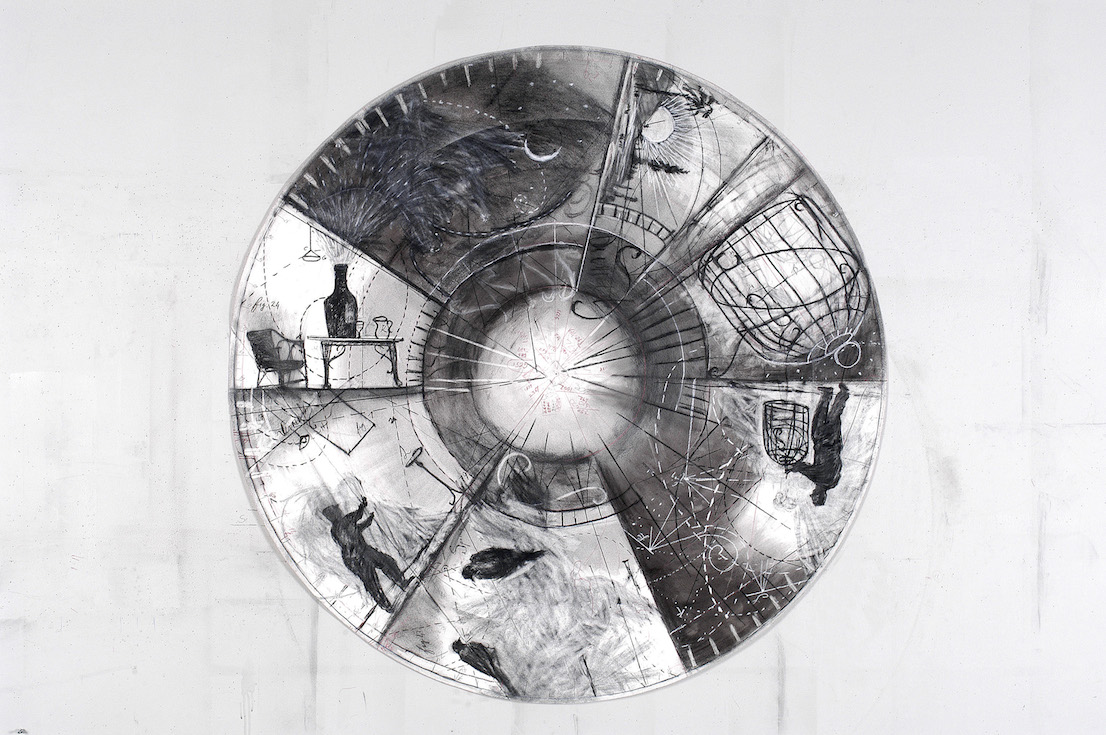

William Kentridge, Particular Collisions, 2013. Courtesy: William Kentridge and Lia Rumma Gallery (Naples and Milan).

William Kentridge, Colonial Landscapes, 1995-96. Courtesy: William Kentridge and Lia Rumma Gallery (Naples and Milan).

William Kentridge, Drawing for The Magic Flute, 2004. Photo: John Hodgkiss. Courtesy: William Kentridge and Lia Rumma Gallery (Naples and Milan).

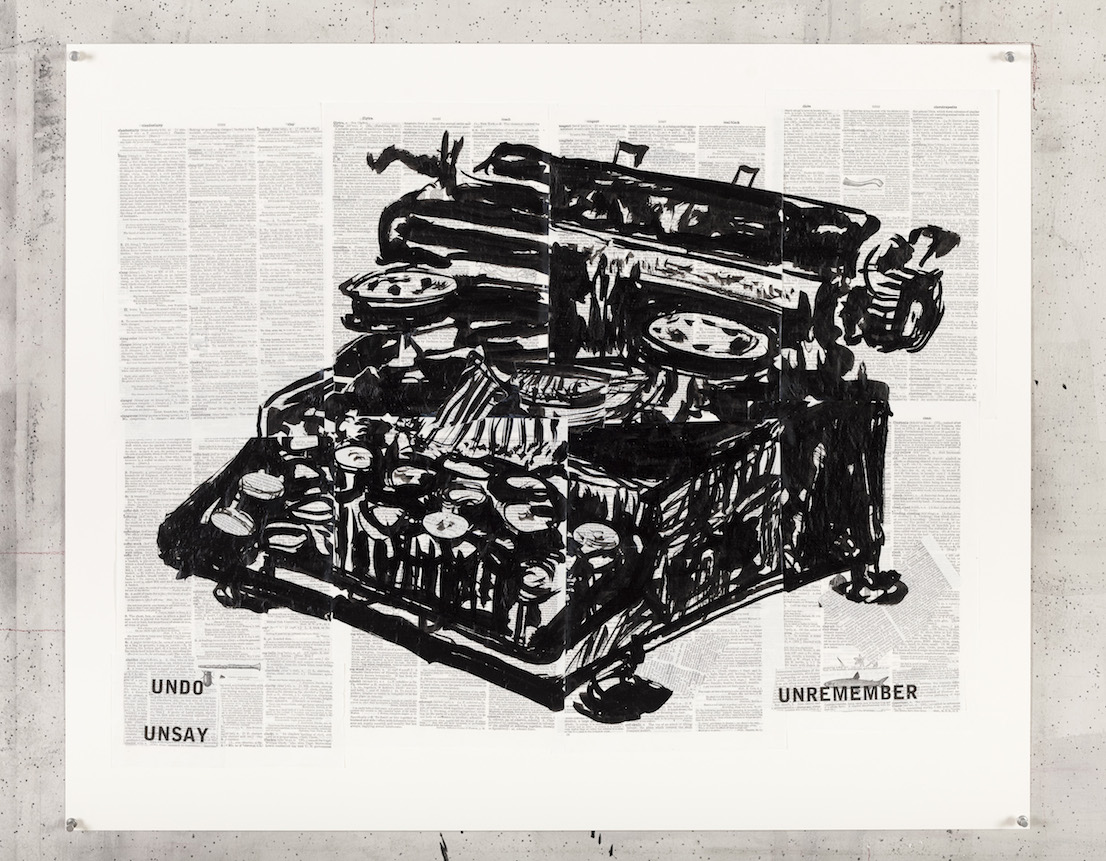

William Kentridge, Undo Unsay, 2012. Photo: Thys Dullaart. Courtesy: William Kentridge and Lia Rumma Gallery (Naples and Milan).

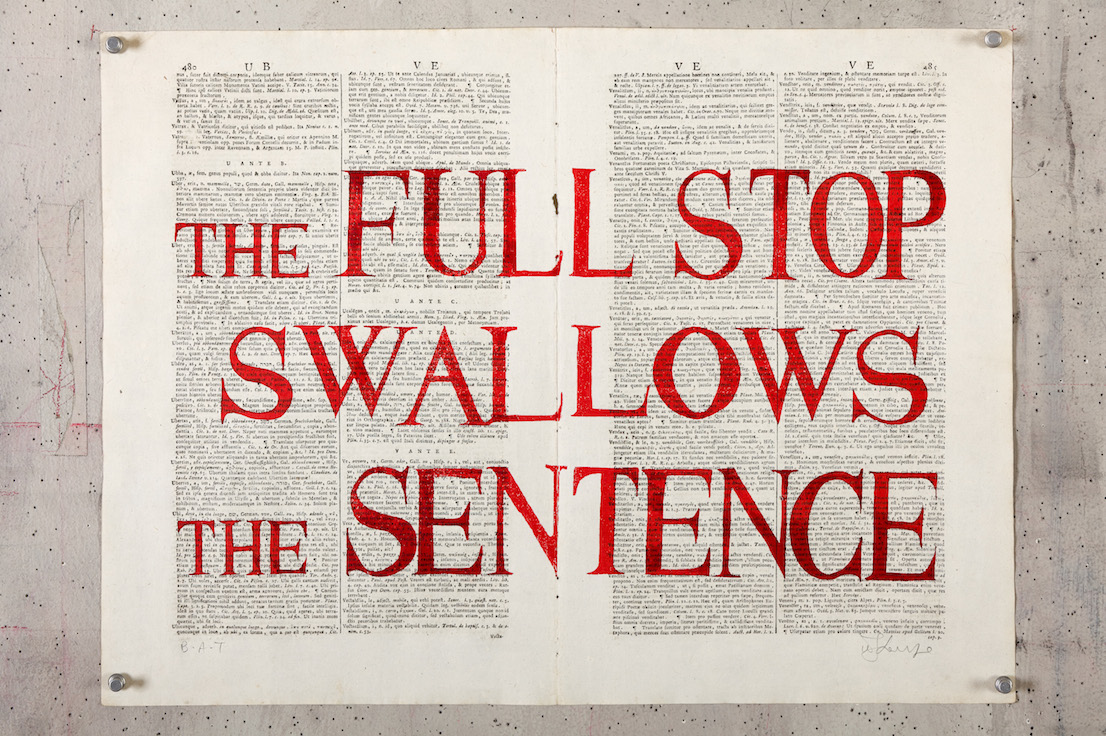

William Kentridge, Rubrics, 2012. Photo: Thys Dullaart. Courtesy: William Kentridge and Lia Rumma Gallery (Naples and Milan).

William Kentridge, Die Zauberföte, 26/04/2005. Le Théatre Royal de la Monnaie, Brussels. Courtesy: William Kentridge and Lia Rumma Gallery (Naples and Milan).