7 December 2012

Tomás Saraceno—born in Argentina in 1973—has the enthusiasm of the experimenter and the romantic lyricism of the visionary. His imagination is peopled by flying cities, hanging gardens and gigantic spider webs. Steeped in the science of engineering and the rationalism of city planning, his artistic practice strives to conceive an alternative future for humanity, that of an existence led on artificial clouds suspended in the air. An architect by training and a pupil of Peter Cook in Frankfurt, Saraceno—winner of the prestigious Calder Prize in 2009—has exhibited at major art institutions all over the world, including the Venice Biennale (2009), the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin (2011) and the Met in New York (2012). His most recent work is on show at the Hangar Bicocca in Milan: the monumental “inflatable” installation entitled On Space Time Foam.

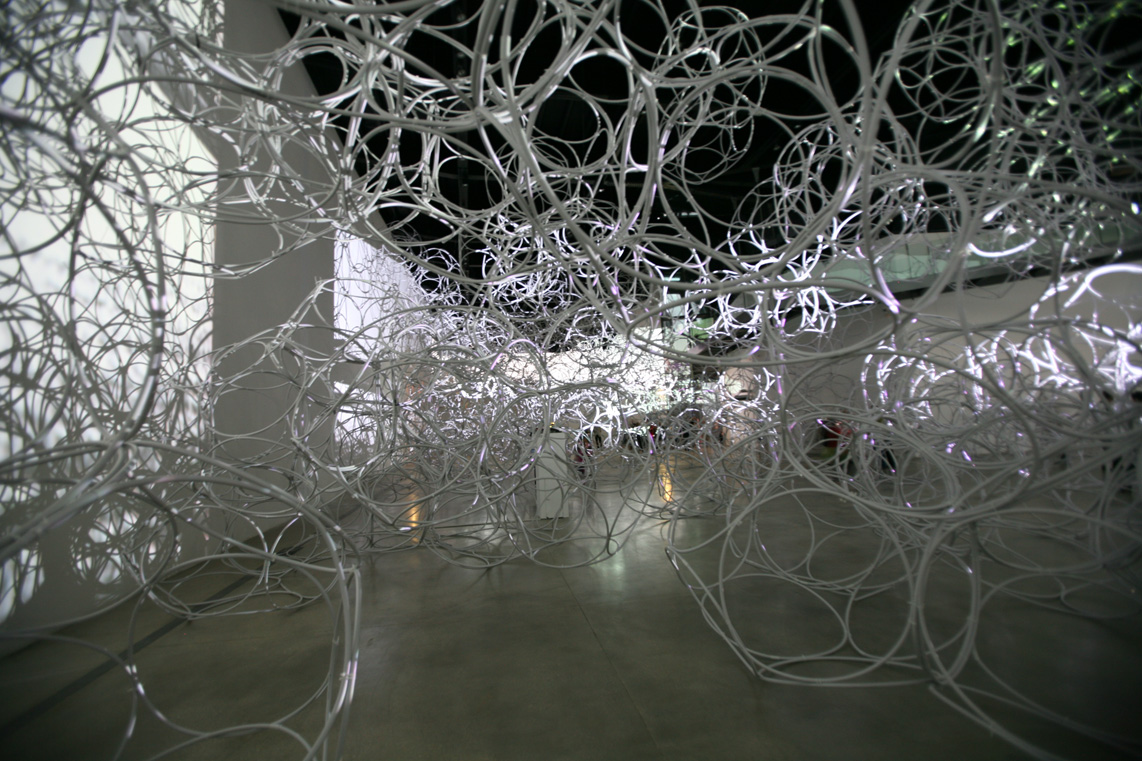

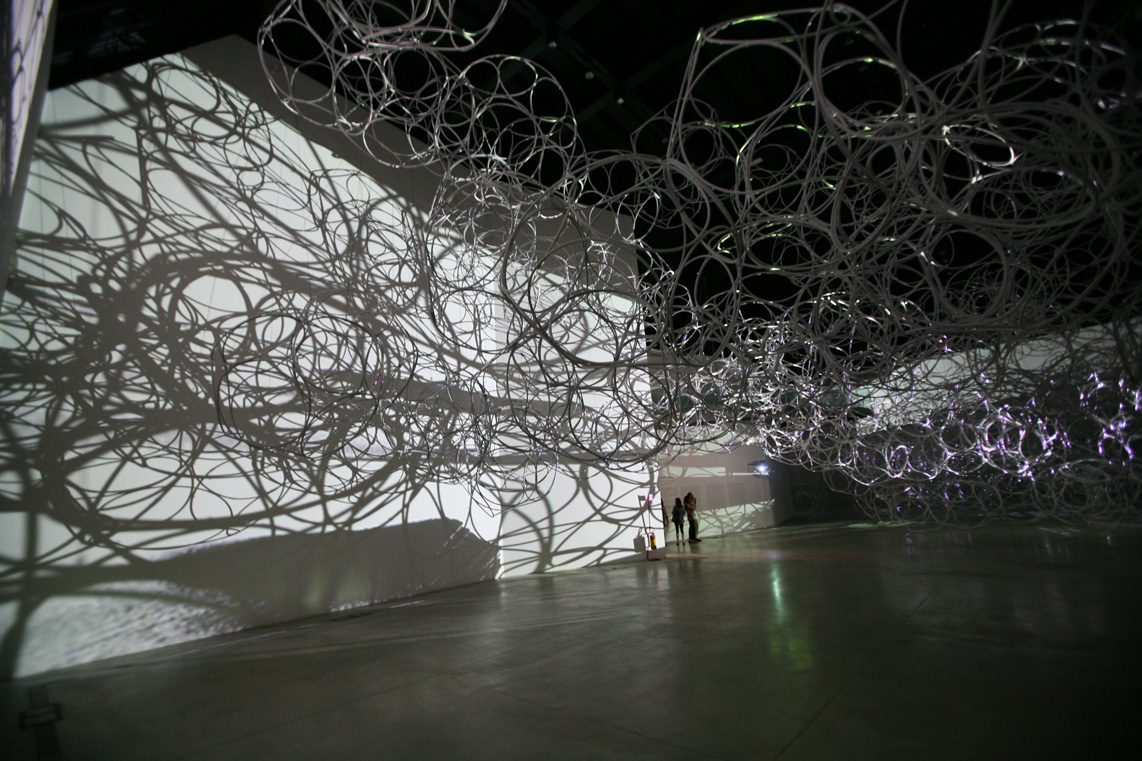

Tomás Saraceno, On Space Time Foam, 2012. Photo: Alessandro Coco. Courtesy: Fondazione Hangar Bicocca, Milan.

Your work calls to mind a celebrated declaration of Italo Calvino’s: “Take life lightly, for lightness is not superficiality, but gliding above things, not having weights on your heart.” All your art seems to take this advice literally, doing its utmost to attain an exemplary lightness, in the physical sense of the term. You want people to live on artificial clouds floating in the atmosphere; you have designed a flying and traveling installation, Museo Aerosolar; you have said several times that your works are made up 99% of air. And finally, in 2009, you took part in NASA’s Space Studies Program, where you carried out studies on gravity. What value does the absence of weight assume in your research as a visual artist?

I find the parallel with Italo Calvino very apt. I loved The Baron in the Trees, the story of a boy who climbs a tree and spends the rest of his life up in the branches, not wanting to come back down to the ground: a paean to the absence of gravity, in a sense. The concept of lightness, in my work, is closely connected with that of suspension in midair. I’ve always been fascinated by a project of Buckminster Fuller’s called Cloud Nine that was based on the assumption that enormous geodesic spheres would be able to float above the ground if the temperature of the air inside them was raised: it would be enough for people to breathe and exhale warm air to make possible inhabited flying cities, transported by the wind. I’m very struck by the fact that as automatic and unconscious an act as breathing could produce such an extraordinary effect. This idea pervades my works, from the suspended structures—part of the Air-Port Cities project—to the modular installation of the Cloud Cities series, including my latest intervention at the Hangar Bicocca in Milan entitled On Space Time Foam.

On Space Time Foam is an enormous floating structure made of transparent film, with a total surface area of 1200 square meters. The installation is accessible on several levels: visitors can walk around at a height of 15 or 20 metes above the ground, trying to keep their balance on a mobile and profoundly unstable surface. The titles alludes to a primordial state of matter, the “space time foam” out of which the universe formed. A taste of what it might be like to live on an artificial cloud. How did you conceive this work?

What characterizes my intervention at the Hangar is the dynamism of the space: the configuration of the work is defined by the people who walk around on it, a sort of sculpture modeled by their breath and their steps. The geometry of my works is strictly dependent on the topology of the space. The case of On Space Time Foam is exemplary of this. The initial plan was to hang a large sphere in midair, suspended by cables from the walls of the Hangar’s Cube. Later the single sphere became two, and then was transformed into a large inflatable structure that was not spherical at all. Several variables contribute to defining its final shape, such as the amount of air, the pressure of the materials and the weight of the people. It is the interaction between all these factors that keeps altering its appearance, as in a sort of artificial ecosystem made up of different but highly interdependent units.

Tomás Saraceno, On Space Time Foam, 2012. Photo: Alessandro Coco. Courtesy: Fondazione Hangar Bicocca, Milan.

An ecosystem in which each person is responsible for the overall equilibrium of the structure.

Exactly. If too many visitors gather at one point, then the surface of On Space Time Foam sinks like a black hole, undermining its overall stability. As soon as you decide to climb onto the installation, you are necessarily caught up in a play of mutual dependence. This experience helps to initiate a dialogue between people, through a body language that has no need of words. I like to think of this work as a kind of software, a computer program or a virtual network shaped by the number of clicks of millions of users scattered all over the world. A sort of inflatable Wikipedia, whose encyclopedic knowledge is built up through the participation and interaction of individuals.

In a few days you’ll be starting a residence at the CAST (Center for Art, Science & Technology) at MIT in Cambridge in the United States. On what will your research turn?

The idea is to continue the investigation embarked on with On Space Time Foam together with a team of scientists and engineers. We will study the possibility of creating a genuine model of habitation based on the transparent film of the work: a sort of floating biosphere to be positioned above the Maldive Islands. In the view of many experts, in fact, in 15 or 20 years’ time the archipelago of the Maldives will be entirely submerged: will it be possible, then, to construct a flying island, transported by currents of air and self-sufficient from the viewpoint of energy? Along with Andrea Lissoni, curator of the exhibition, I have thought a great deal about possible developments of the project and the residence at MIT is the first step in this.

On Space Time Foam can be considered part of a series of works aimed at creating airborne platforms that people can live on and that will be environmentally sustainable, of possible alternatives to an existence on the Earth. In Argentina you received a training as an architect and your interventions take on the characteristics of a utopian urban project for new solutions of habitation. What value do you assign to artistic practice in relation to planning and scientific research?

In my work as a visual artist I do not set myself the objective of coming up with definitive answers. I don’t like to use words like “solutions for habitation,” nor am I under the illusion of being able to make concrete “improvements” in the life of humanity as a whole on the planet. Rather my works are trials, experiments for presumed and possible futures. The aim of what I do is to try to expand the range of the dialogue, to make as many people as possible aware of the extent of the impact that each of us has on others and on the environment. This is the objective of my artistic practice: awakening people to the interdependence of the different elements that make up the system in which we live—the interrelations between objects, natural phenomena and living creatures. It is the idea at the root of the short scientific documentary Powers of Ten, made by Charles and Ray Eames in 1968 and based on the book Cosmic View by Kees Boeke (1957): the existence of an indissoluble link between the different orders of reality, from the infinitely large to the infinitely small, from galaxies to quantum particles. A great inspiration for my work has been and still is the French philosopher Félix Guattari, author of The Three Ecologies (1989), in which the traditional notion of ecology is reexamined and extended to other spheres of interest: environmental ecology, social ecology and mental ecology, the last of which makes the psyche and the realm of human subjectivity its field of inquiry. What characterizes the territories of the three ecologies is the fact that they are open and closely correlated systems.

What you’ve just said reminds me of the words of the French sociologist Bruno Latour, who describes your practice as “a potent attempt at shaping today’s political ecology—by extending former natural forces to address the human political problem of forming livable communities.” The reference to Guattari is crystal clear.

Bruno Latour, in this passage, is alluding in particular to the work that I showed at the Venice Biennale in 2009, entitled Galaxies Forming along Filaments, Like Droplets along the Strands of a Spider’s Web. It was a gigantic three-dimensional spider’s web made of elastic ties hooked to the walls and mounted in such a way as to form “webs” and “spheres” closely connected with each other. Latour saw this structure as the representation of a social theory founded on a heterarchical rather than hierarchical principle, an organization of society defined by the dialogue between cultures and the extension of the bounds of global communication while respecting local realities.

Tomás Saraceno, Galaxies Forming along Filaments, like Droplets along the Strands of a Spider’s Web, 2009. Photo: Alessandro Coco. Courtesy: © Studio Tomás Saraceno.

Finally, let’s talk about the people who have had an influence on you. You belong to the tradition of a certain radical architecture, with a utopian bent: I’m thinking of architects active in the second half of the 20th century like Buckminster Fuller, whom you mentioned earlier, Yona Friedman and Frei Otto. In addition, you were a pupil of Peter Cook, the founder of Archigram, at the Städelschule in Frankfurt. To what point do you feel influenced by this vision of design?

To the names you have cited I would that of Gyula Kosice, an Argentinian artist of Slovak origin and the inventor of hydrospatial cities. I got to know him personally while I was studying architecture in Buenos Aires: his utilization of space as well as his unique poetic inspiration made a great impression on me. As for Fuller and Friedman, I dedicated to them the title of a work of mine exhibited at the MACRO in Rome in 2011: Cloudy Dunes. When Friedman Meets Bucky on Air-Port-City, a true homage to their ideas. In particular, I have always been fascinated by Buckminster Fuller’s attempt to expand the processes of the sharing of material resources to humanity as a whole, and not just to a small part of it. Perhaps this is the greatest lesson that I have learnt from those teachers: the effort to share out what belongs to everyone, in an act of extreme generosity.

Tomás Saraceno, On Space Time Foam, 2012. Photo: Alessandro Coco. Courtesy: Fondazione Hangar Bicocca, Milan.

Tomás Saraceno, Museo Aero Solar, 2011. Courtesy: Museo Aero Solar.

Tomás Saraceno, Museo Aero Solar, 2011. Courtesy: Museo Aero Solar.

Tomás Saraceno, Cloudy Dunes. When Friedman meets Bucky on Air-Port-City, 2006. Photo: Alessandro Coco. Courtesy: © Studio Tomás Saraceno.

Tomás Saraceno, Cloudy Dunes. When Friedman meets Bucky on Air-Port-City, 2006. Photo: Alessandro Coco. Courtesy: © Studio Tomás Saraceno.

Tomás Saraceno, Galaxies Forming along Filaments, like Droplets along the Strands of a Spider’s Web, 2009. Photo: Alessandro Coco. Courtesy: © Studio Tomás Saraceno.

Tomás Saraceno, Cloud Cities, 2011. Photo and Courtesy: © Studio Tomás Saraceno.