14 December 2017

To get themselves noticed, photographers usually try to develop a consistent and recognizable stile. This rule does not hold for Thomas Ruff, one of the most celebrated of the artists working in the field over the last forty years. His pictures, taken between 1979 and the present day, are currently on display in two solo exhibitions, at the Whitechapel in London and the Fondazione Mast in Bologna. Ruff, a prolific artist affiliated to the Düsseldorf School—founded by Bernd and Hilla Becher—that turned documentary photography into a conceptual instrument, has reformed the politics of images, ranging across the genres: from the portrait to porn, from photojournalism to forays into the domestic and architectural sphere, from war to the cosmos. His work creates a short-circuit between the act of looking and that of thinking critically about images, interrupting the spontaneous relationship between viewer and representation in modern consumer society.

You studied at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf and are still referred as belonging to and representing the so-called Düsseldorf School. It’s a label that you share with you old classmates Andreas Gursky, Thomas Struth, Candida Höfer and Axel Hütte. Besides most of you having studied with Bernd Becher and still living in Düsseldorf, is there anything else you still have in common with them?

When I joined Bernd Becher’s class in 1977/78, it was a historic situation that’s gone now and is never going to occur again. We all started more or less the same way, with large format cameras trying to make the most of documentary black-and white-photography. Everyone was looking for a photographic subject that no one else was working on, in order to stand out from the others. That was 40 years ago, and in those 40 years a lot has happened. We all followed different paths: Andreas developed his extremely large and composed imagery, Thomas is still working in a straightforward manner, as is Candida Höfer, who is probably still the closest to Bernd and Hilla Becher, while Axel concentrated on his version of landscape imagery. I went off on investigating on the structure of photography. So the starting point for all of us was similar, but then we diverged.

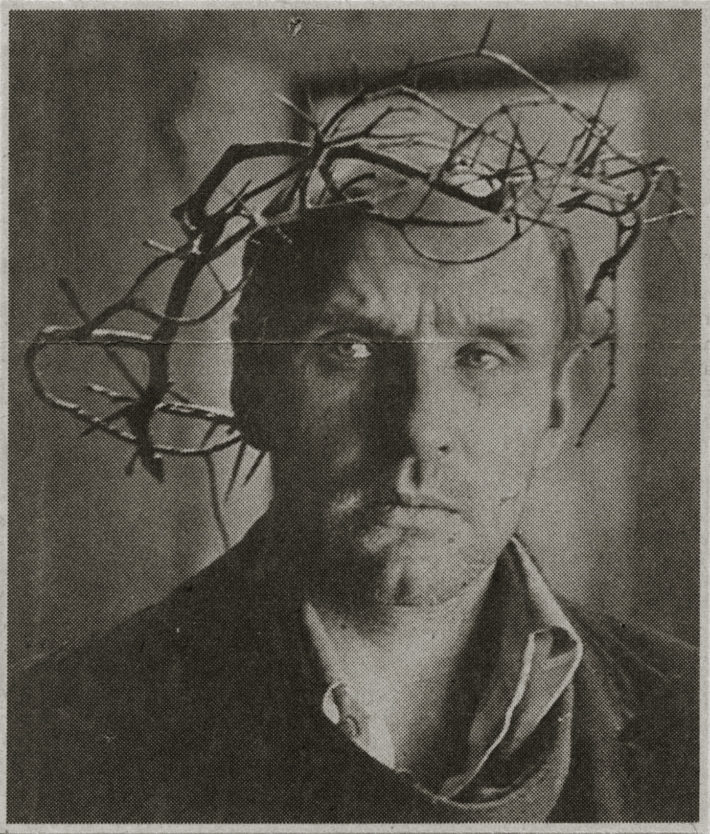

Porträt (P Stadtbäumer), 1988. © Thomas Ruff.

The large format camera allowed you to experiment with size and obtain large and detailed prints. Do you think size is as significant a feature of the photographic artwork as the camera or printing process?

Yes indeed, size is very important for the image itself. I chose a large scale for the Portraits (160 x 210 cm) because I wanted their physical presence to be overwhelming. But depending on the different series, the size can be small, medium or large. To choose which size is the right one, I print samples of the first images in a series in various sizes, stick them on the wall in my studio and all the prints but the right one “fall” off the wall.

Moving on to subject and ideas, as a teenager you shot the landscape of the Black Forest where you grew up. Later on, however, despite investigating many genres in photography, landscape was never the main focus of your work as an artist. Why?

It’s natural to investigate what is nearby. Back then I was living in the countryside—so landscape was what I was looking at. When I went to Düsseldorf to study, there was no landscape anymore, so I had to tackle other things. Maybe it’s also the lesson I learned from Becher: concentrate on your subject: if you decide it’s going to be the face, you should make a straightforward portrait and not have a distracting landscape in the background. If you shoot interiors, then that’s what you are looking at. It’s the same with buildings. In this sense I was as strict as Bernd and Hilla Becher. A very diverse taxonomy of subjects, none of which was just landscape.

Interieur 1A (Interior 1A), 1979. © Thomas Ruff.

The Becher’s typological grid you are referring to evokes an objective and detached perspective on the subject. Yet when it comes to detecting sources and influences, it all seems to be linked to a very private experience.

The initial choice of a subject always stems from a personal interest, and then by thinking about the image and working on it, it changes from an individual interest to a more collective one. If I go back to the first series, the Interiors, currently showing at the Whitechapel, I started working on them a year after I had left home. Just like the other students in the Becher class, I was looking for a subject I was familiar with and had easy access to—so that was probably the real reason behind choosing to photograph my parents’ house, my friends’ parents’ house and my own apartment, which by the way I didn’t leave for the next twenty years! If you look at the Portraits instead, I was just over 20 years old and only knew my generation. I didn’t know any small children or old people, so young people in their twenties became the center of my work. The Buildings series was a natural derivation of both Interiors and Portraits: once I had photographed the living spaces and the people who inhabited them, the next step was to look at the cityscape that surrounded us. I never think about this theoretical framework before I start working but react spontaneously to my personal surroundings.

press++21.11, 2016. © Thomas Ruff.

What is the passage, in your case, from photography to the work of art?

It’s very simple: in my everyday life, images show up and I can’t get them out of my mind, and so I start working—researching about the image, trying to find the core of it. In the end it’s all autobiographical.

Your approach reminds me somehow of MoMA photography curator John Szarkowski’s words about Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander and Garry Winogrand in the preface to the catalogue of the exhibition New Documents in 1970. He wrote they “redirected the technique and aesthetic of documentary photography to more personal ends. Their aim has been not to reform life but to know it.” Do you think subjectivity in photography is enough to make a revolution?

The German equivalent of Szarkowski is Klaus Honnef, who published several books on photography and emphasized the importance of the power exercised by the media over art. But is photography truly authentic and objective, or is it not always related to the position of the photographer in the world? I think photography is always the output of a specific time and can only take in a small, very special part of the world. Sometimes this can be very interesting, but sometimes also boring. But what do you need to “make a revolution?” I don’t know. I just believe that you should not only use the medium, but also reflect it.

jpeg ny01, 2004. © Thomas Ruff.

The medium of photography varies greatly in its aims, from tracing reality—a “pencil of nature” to quote William Fox Talbot—to more conceptual pursuits. You have explored much of its potential through series like Negative, press++ , Substrates and jpeg, all of which are part of two anthological exhibitions, at the Whitechapel in London and the Fondazione Mast in Bologna. So my question is: from your special vantage point, in which direction is the medium heading?

The medium will just go on. The abstract work and the “pencil-of-nature” work are just two possibilities for photography. I myself have used lots of different techniques and this will continue. I will carry on with my private interests, moving back and forth between the virtual and physical elements of photography. I don’t care about technology per se. I will always choose the technique that resonates with the image I want to create. It can be state of the art or it can be old-fashioned and nostalgic, as people say when they look at my press++ works. As for the future of photography, this prediction should be made by sociologists or philosophers.

Rather than of nostalgia, I would speak of danger. There is always something sinister in your pictures.

Maybe this is because I am skeptical of the image world itself. The worlds depicted in photography disappear. People lose their familiarity with a certain kind of photography—like the analog one—and photography itself changes. But I can study the different approaches, no matter which period they come from or what they represent. I don’t feel time to be a limit.

Haus Nr.11 III (House Nr.11 III), 1990. © Thomas Ruff.

With regard to the Photograms, homage to a practice that dates back to the Bauhaus and Modernism in general, I have read that you were inspired by two Arthur Siegel photograms you bought for your photography collection. Is collecting an important source of inspiration?

It’s a source, but not the only one. My photography collection is not based on an idea of quality. It’s a very personal collection. Half of it is probably made up of astronomical photographs, while the rest consists of strange technological and badly overexposed photographs—I’m very fond of them. I actually bought most of them at small French auction houses, as they sometimes have incredible stuff. In a way, what I’m seeking for my collection is the error in photography, images that show different ways of using the medium, some of them with very strange outcomes. In my eyes these photographs are great, because they are so strange. And before they disappear, I collect them. Maybe I am like the characters in Flaubert’s Bouvard et Pécuchet.

16h 30m / -50°, 1989. © Thomas Ruff.

Photography has “died” many times, each time a new technique arises and sweeps away the old one. This cycle of birth, death and rebirth is taken to extremes by the speed of technological development. This is why I see photography, and especially the collecting of photographs, as an experience close to that of mortality, and I think your work fits with this vision. Do you feel the same?

The cycle of birth, death and rebirth is a universal principle—I guess it’s what evolution is about. Just the pace has changed, and not only in the technology of photography. Of course, if you look at a collection of photographs, you are looking back into the past and you experience mortality. In the same way, my investigations of photographic sources and ideas are research into the past, trying to keep it for the present. Maybe the way to put it is that I’m trying to work on a jigsaw puzzle about photography, and all the works or series are part of that puzzle, with the pieces sometimes fitting into each other, while at others holes are left. However, I don’t think the puzzle will be complete by the time I die.

How does it feel to look back at works like Nacht, which was a response to watching the First Gulf War on television in 1991 from the guilt-ridden position of a voyeur? I find the visual representation of war is even more critical today, in the aftermath of two more Gulf Wars and the Arab Spring.

My interest is not so much in war anymore but in political practices. I find the political agenda to be more and more just a matter of propaganda. During the most recent Third Gulf War led by George W. Bush, photojournalists were not allowed to document the reality of war anymore. Images were mostly prefabricated and underwent very strict vetting before being sent out. In the First Gulf War, instead, the imagery was quite naïve.

Nacht 9 II (Night 9 II), 1992. © Thomas Ruff.

In an era that seemed to promise a democratic and free view of the world, as a consequence of the digital revolution and the spread of the internet, we are paradoxically hostages of a manipulated, staged and Photoshopped imagery. Do you think the idea of a diverse, candid and unfiltered visual experience has been lost forever?

Yes, I don’t think there is a free circulation of images. The production of images itself is very diverse and spontaneous, but the images that are chosen by the media and by governmental agencies to be used and shared are only the ones that consolidate the dominant position. The politics of pictures is brutal, because political, social and economic interests always control it.

Zeitungsfoto 101 (Newspaper Photograph 101), 1990. © Thomas Ruff.

Do you foresee an even greater deviation between the potential of photography and what is in circulation?

Probably. We are coming from the apocalyptic vision of George Orwell’s 1984, and are heading towards the dystopic one of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. I look at my kids now, the way they use their smartphones, growing up with advertisements, Snapchat and social media. They adapt and imitate what they see. They have no critical approach and are thus the victims of a gentle brainwashing.

I believe that also derives from the fact that today photography is assigned a growing value linked to the ease of its distribution in the digital world. A value that has a cost, because noting—on Facebook, Instagram or Snapchat—is free of charge. It is just a matter of defining what is being exchanged in the transaction: time, attention, data. We could also say that the internet companies represent a challenge for artists, but in reality this is not so. How do you react to this phenomenon as an artist?

Do I have a chance? I can only reach 0,0001% of people.

I read that before becoming an artist your dream job was to work for National Geographic and take on the role of the documentary photographer. You never pursued this option. Was your decision based on a reality check?

Yes and no. National Geographic and plenty of other magazines that I was reading between the ages of 10 and 20 were very widespread in the 1960s and 1970s, and they made many promises about beautiful things going to happen and fascinating places to see. Earth looked like an amazing place to live and travel around. But the promises were not fulfilled at all. If I look at the world today, there are a lot of places I don’t want to travel to, because they are dangerous. There are others that you shouldn’t go to because they are extremely polluted or the people are suffering from hunger and dictatorship. The question was, then, how to react with photography to this awakening to reality? On the other hand, I also learned that Becher’s way of taking photographs was not the only one. There are thousands of different ways of doing it. I am a fan of Sebastião Salgado, for example, and I have noticed I am often interested in photographic work that doesn’t come out of the artistic field, as it happens to be truer than photographic work produced for the art market. When I look back I see that over the last forty years there have been astonishing technological changes in the camera and in the distribution of photographic images. And working with photography, I believe you should include, think about and deal with these issues.

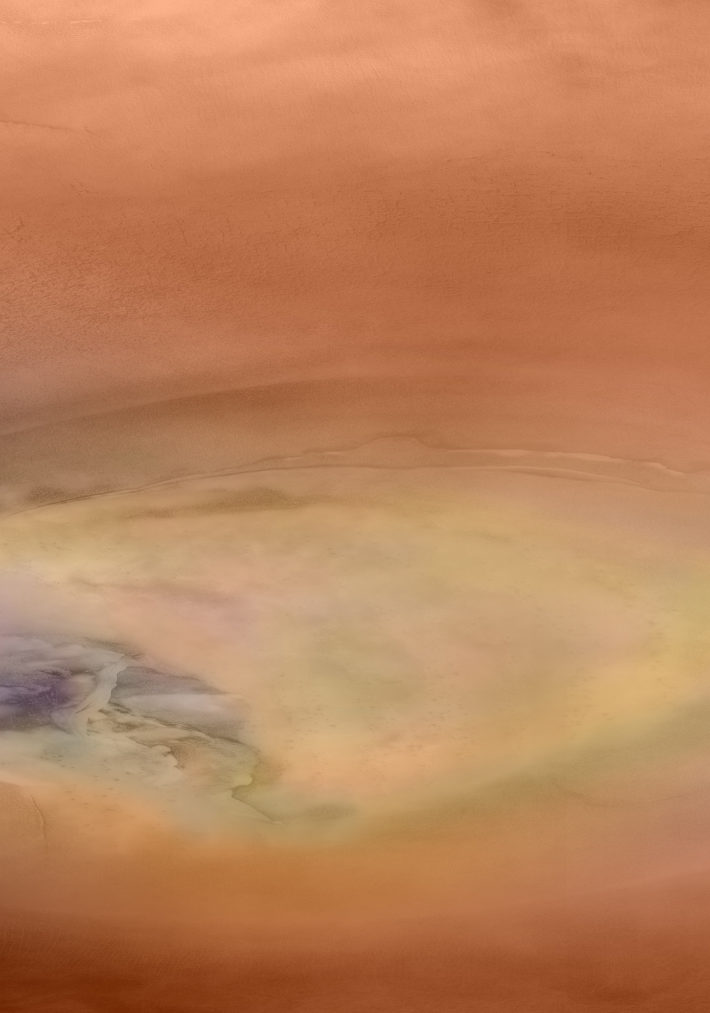

ma.r.s. 01_III, 2011. © Thomas Ruff.

Outer space is a subject you have often tackled—in the ma.r.s. series, for example. Its representation is closely bound up with the evolution of technology. There, the simple act of looking or editing is not enough, because space is invisible to the human eye. What are the instruments available today?

You should ask a physicist or an astronomer—they might know. Electromagnetic radiation in the universe ranges from 10,000 to 10-17 meters in wavelength, but for the naked eye the visible spectrum is between 380 and 640 nanometers. A telescope might be able to capture a wider spectrum, but it would need technical additions to make that light visible. Radio telescopes are picking up electromagnetic waves you can’t detect with the eye, and with certain tools you can also visualize them. So actually, if we want to look at space more accurately, we should use different prostheses and not only the camera. Photography is only a small part of our access to understanding things in space.

Have you ever thought about moving to another medium in order to tackle space better?

What kind of medium are you thinking of?

I don’t know what instrument or what technology. Something that reflects a more profound research into the act of looking. What are we really looking at when we observe outer space?

You look into a past that goes back 14 billion years and you look into a space that you can’t imagine. It is just too much for our small human brain.

Substrat 31 III (Substrate 31 III), 2007. © Thomas Ruff.

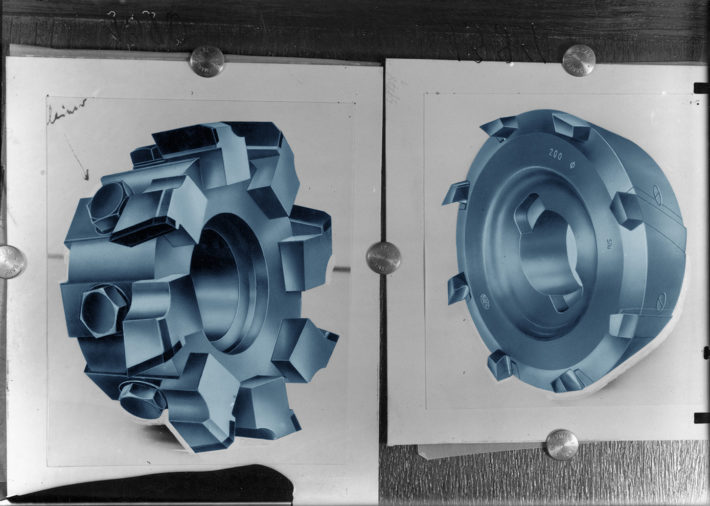

Maschine 1390 (Machine 1390), 2003. © Thomas Ruff.

phg.07_II, 2014. © Thomas Ruff.

nudes lk18, 2000. © Thomas Ruff.

jpeg CO01, 2005. © Thomas Ruff. Courtesy: Thomas Ruff and Lia Rumma Gallery.

© Thomas Ruff.