18 December 2014

The work of the Montenegrin artist Irena Lagator Pejović turns around the themes of space and the relationship between individuals. Soliciting the interaction of the viewer, her installations, videos and photographs reflect on topics like the perception and understanding of reality, individual and collective identity and the responsibility of society and its single members. Lagator Pejović represented Montenegro at the 55th Venice Biennale (2013), while the most important exhibitions in which her work has featured are the sea is my land at the Milan Triennale (2014) and the MAXXI in Rome (2013); Mines of Culture—From Industrial to Art Revolution, Labin Art Express (L.A.E.) XXI, Croatia; Coexistence: for a New Adriatic Koine, Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Rijeka, Croatia (2014); Spring Exhibition 2013 at the Kunsthalle Charlottenborg in Copenhagen; The Society of Unlimited Responsibility at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Belgrade. In 2012, while she was artist in residence at the Neue Galerie Graz am Universalmuseum Joanneum her first book The Society of Unlimited Responsibility. Art as Social Strategy. 2001-2011 was published by Buchhandlung Walther König, Cologne. Lagator has two exhibitions scheduled for 2015: Fiery Greetings at the Museum of Yugoslav History in Belgrade and Coexistence at the Fondazione Pino Pascali in Polignano.

You were born in Cetinje, Montenegro, in 1976 and stayed in your country till you completed your studies at university in 1999. So you belong to the generation that grew up during the wars of the nineties. How was that experience for you and how has it influenced your artistic research?

The period of the wars in Yugoslavia had a profound influence on me. But the context in which my generation grew up before the conflict was very important too: the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia was a multicultural state and a land midway between East and West. Young people were raised under the motto of Unity and Fraternity—a concept that implied respect for the other, a meeting between cultures and constant communication. So for my generation it was particularly hard to accept the fact that the reality of war had replaced the “fairy tale” of Unity and Fraternity which had been fed to us.

How did you react to this disorientation?

It made me very soon understand the absolute importance of individual responsibility, of the choice between a passive acceptance of the new walls erected by society and the attempt to break them down personally. I started to ask myself existential questions, not linked solely to the wars, but also to politics, economics, the role of the other in society and belonging to a given culture for geographical reasons.

In your works you often tackle themes from everyday life, people’s desires and expectations. Can you tell me something about the installation Witness of Time—Now?

In 2002 I presented a work of mine entitled Reconstruction at the 4th Cetinje Biennale. I had been struck by the story of a condominium in my city that, under construction since 1987, had only been completed in 2002. The company that owned the property had sold the same apartments to several families, and they had reacted by bringing an action in the courts. So I decided to track down the proprietors, photograph them going about their daily activities and install blowups of the pictures on the open shutters of their empty apartments. In this way public space became a mirror of people’s real problems, and the starting point for a reflection on social responsibility. Passing in front of the building, the observer does not see just my photographs, but also the empty interiors of the apartments. Thus I succeeded in creating a diptych of anthropological and phenomenological questions, focusing on one that was to become central in my artistic investigation: the meaning of the term S.r.l. [the equivalent of the English expression, LLC, Limited Liability Company, translator’s note] from a social, legal, commercial, juridical and economic point of view.

Irena Lagator Pejović, Witness of Time – Now, 2002. Photo: Lazar Pejović.

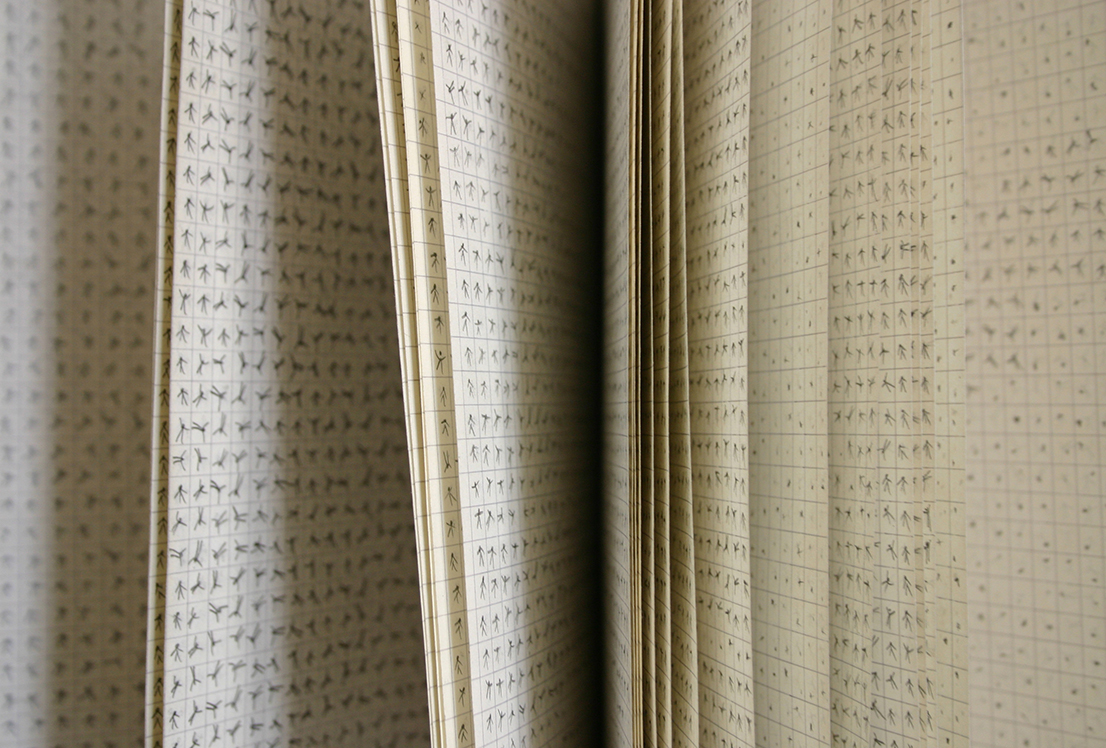

In 2006 you coined the term Society of Unlimited Responsibility and conceived a work with the same title: a school exercise book in which you drew an endless number of human bodies that turn on themselves, each resembling and yet different from the next. The individual and the multitude, the single and collective identity: why this title and what significance does unlimited responsibility take on in this work?

During a residence at the Neue Galerie in Graz I decided to spend my time drawing endless pictograms of a human figure that rotates around itself. This started me off on a long process of reflection on the role of the individual and on the sharing of experiences in common space. What interests me is to recreate the sociological phenomenon of responsibility because, living in a world racked by war and globalization, I noticed that what is lacking is the capacity to look at the primary elements needed to develop a peaceful and responsible society. After long research in the fields of economics, politics, history and etymology I came up with the idea of a society of unlimited responsibility. Today the question of responsibility is a crucial one, and the gesture of turning limitedness into unlimitedness allows me to criticize the world that on the one hand remains too limited in its responsibilities, and on the other knows itself to be unlimitedly responsible when it is a matter of the destruction of a culture, a people or a society. I asked myself the following question: how can we call ourselves a society if we declare our social responsibilities limited? Where is the development of a world characterized by more and more limited responsibilities and less and less responsible societies taking us?

Your work is a response to these questions?

The Society of Unlimited Responsibility is founded on the artistic postulate that the foundation of the world should be an unlimited and universal sharing of experience, knowledge and responsibility. In art, in fact, all cultures coexist and there is no responsibility without interaction, participation and compassion.

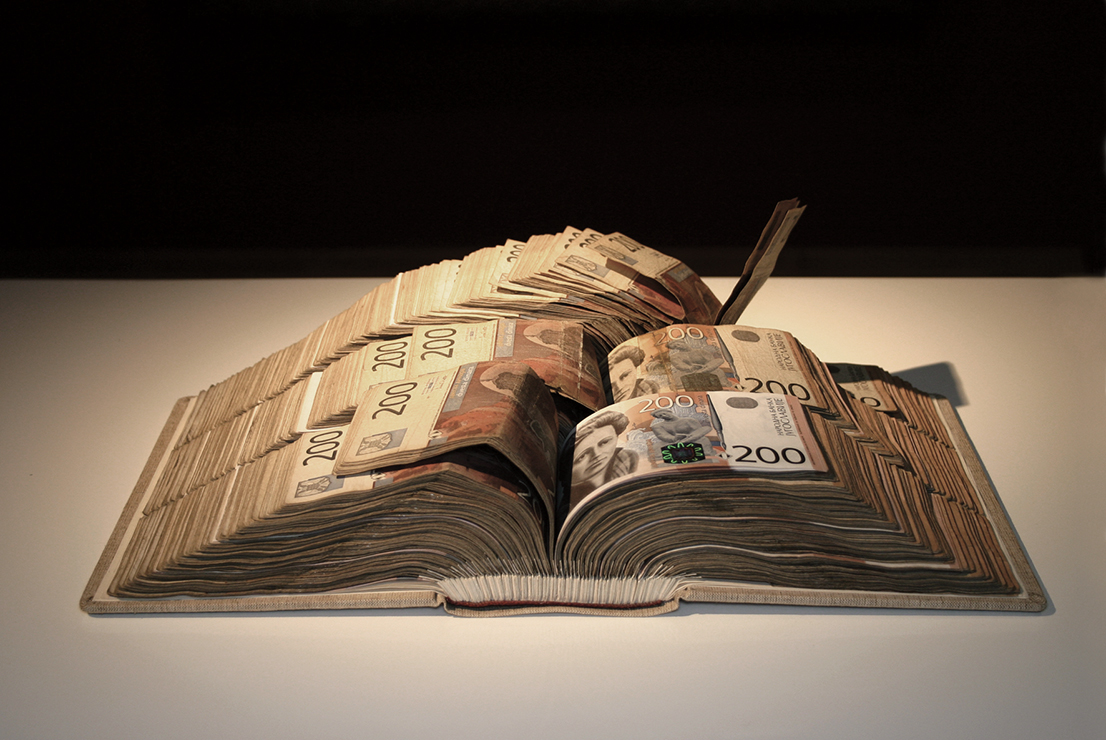

In 2007 you produced an artist’s book, After Memory. Unlike the exercise book with your pictograms, this contained 1800 banknotes each worth 200 dinars. What does this work represent?

On the occasion of the 24th Nadežda Petrović Memorial, the oldest biennale in the former Yugoslavia, which was entitled Transforming Memory. The Politics of Images, I came up with a project dedicated to Nadežda Petrović, a female painter who lived in the years spanning the 19th and 20th century and who spent her whole life working for the creation of Yugoslavia and the unification of its cultures. Studying her story I had discovered that her image had been used on the 200-dinar banknote. In addition, I had noticed that those same banknotes, in 2007, still bore the name of the state of Yugoslavia. So I decided to create a book that would be made up of the banknotes and assemble different cultural, social, political, economic and geographic aspects in a single object. The work began as an artist’s performance without an audience, with a request to the governor of the National Bank of Serbia for a loan to make a work of art. I promised that I would return the notes, but in the form of a work of art for the collection of the Museum of the National Bank. The money was still legal tender, but was soon to have been withdrawn as it still bore the name of the National Bank of Yugoslavia. So with this book I would be able to preserve forever the iconic value of a currency that had united different peoples, and the historic value of the word Yugoslavia. Finally, the use of the banknotes had made me realize how important the material had become for me: money has a very strong sensory component, both tactile and olfactory. Giving importance to the medium out of which my works, my life, my desires are made constitutes another fundamental aspect of my research.

Irena Lagator Pejović, After Memory, 2007-2008. Photo: Irena Lagator Pejovic

The choice of material is a focal point of your work. I’m thinking in particular of the works created with threads, with yarn: why did you choose yarn, a mutable and ephemeral element?

It all starts out from the experience of the viewer in the space. I analyzed the meaning of spatial installations, focusing on the one hand on the choice of the material and on the other on the quality of the visitor’s experience and perception. Yarn is not just a material that is easy to get hold of, but has a much broader semantic, historical and cultural value. In many cultures you find the expression “losing the thread,” which by contrast refers to the desire to maintain a relationship with one’s own culture, one’s own roots and to the mutability of the contemporary world. To obtain the material I turned to the big textile manufacturers, discovering an infinite variety of yarn, of different colors and thicknesses, sometimes so thin as to be almost invisible. So I investigated the importance of light. In the various installations constructed out of yarn [Please Wait Here, 2005, at the church of San Zeno in Pisa, and Own Space, 2006, at the Neue Galerie in Graz, author’s note], light is an integral part of the work and changes in relation to the colors and thicknesses of the yarn, while the experience of the space changes in relation to the interaction of the visitor. Time and the ephemeral are the central elements of these works. The viewer develops, modifies and concludes the work. Observers explore their own perceptions and realize that their presence counts and gives meaning to the work for subsequent visitors.

In 2013 you represented Montenegro at the Venice Biennale with three site-specific installations. In the first, Further than Beyond, you chose a single color, gold, and created two tetrahedrons that preclude any interaction with the viewer. Why this choice?

The slender golden threads of Further than Beyond are arranged horizontally because they allude to the question of social horizontality. Today, with the breaking down of so many frontiers there are no longer divisions between worlds. So visitors find themselves in a gilded setting with a horizon that symbolizes the opening to the other. But they cannot interact with the threads, and so the interaction shifts to a mental level of intellectual awareness. Thought overcomes physical walls. In this sense, Further than Beyond is a manifesto against vandalism. In addition, the choice of gold has a historical significance and is a reference to conceptual research into the history of the contemporary image: on the one hand it alludes to Byzantine influences on my culture and the history of Venice, on the other it takes on a role of social categorization.

Irena Lagator Pejović, Image Think, 2013. Photo: Dario Lasagni, Lazar Pejović.

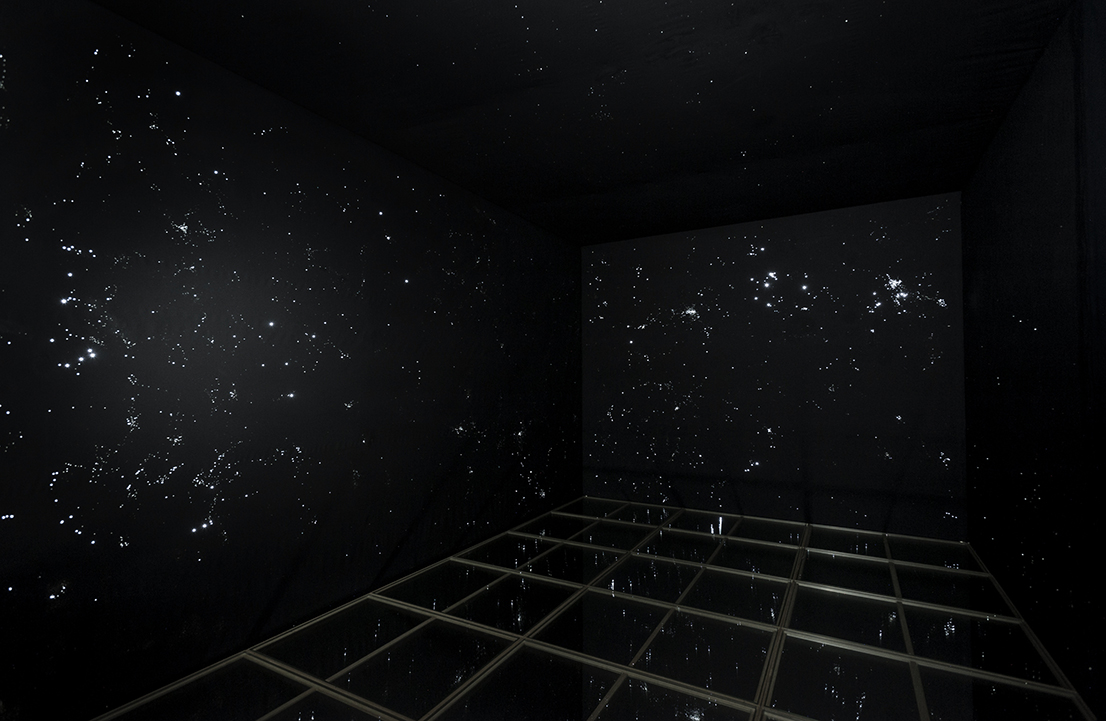

The second work, Image Think, is a room in which the floor is covered with mirrors and the ceiling and walls are covered with black polyethylene and perforated with needles to make holes that let light through. What relationship is established between the viewer and the space, between the perception of what is real and what is reflected by the mirrors?

Entering the second room of the pavilion visitors find themselves completely in the dark, in a sort of black box. Perception of the space is activated only by gaining experience of the place through the physical exploration of seeing in the dark. Thus visitors discover they are walking on a floor composed of mirrors. The role of the mirror is reversed. I wanted to pose new questions about the nature of reflection: from a reflected I to a shared We, from the top to the bottom, to the base of things. Here what is mirrored first is the darkness of light, and so we have a reflection of our negative: once again, we are responsible in an unlimited and no longer a limited way. The polyethylene environment is perforated by thousands of needles and creates the image of a distant universe made up of infinite constellations. It is ourselves and our reflection that interrupts this image of the space, as we walk on the mirrors. What I wanted was to put visitors in a position to discover the world around them and make it visible through a process of taking responsibility for their own actions. And to raise crucial questions: who is the creator of reality? Is it us or society that creates the individual? How do we distinguish the creation of things from their use, and how can we be responsible for things that we do not understand? In addition, the title of the work, Image Think, comes from Orwellian Newspeak. I left the verb in the infinitive, in an attempt to activate mental images and individual responsibilities in order to go beyond the limits imposed by totalitarian regimes.

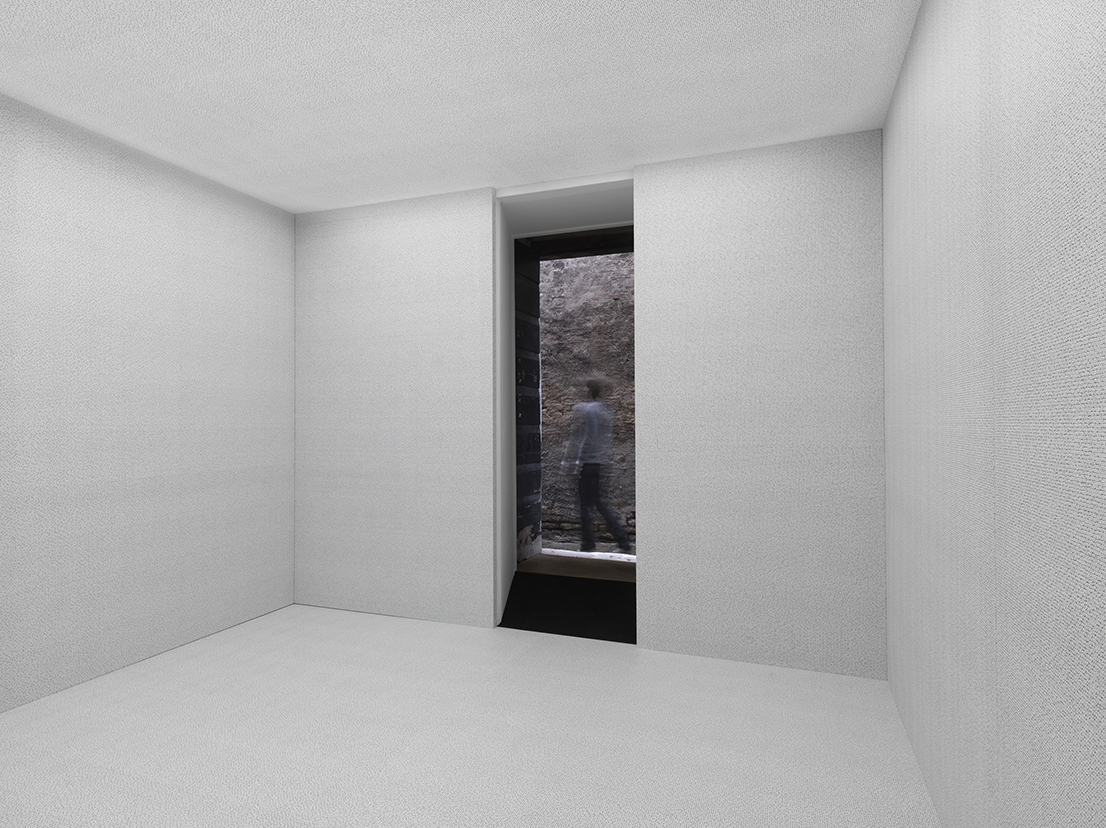

The last work, Ecce Mundi, is a room lined with white canvas on which you have drawn and printed tiny human bodies turning around their axis. What has changed with respect to the school exercise book in which the same pictograms were drawn on sheets of paper and what relationship or contrast is created with the two previous rooms?

The pavilion was an open circuit, so the visitor could choose whether to enter the white room first and exit from the golden room or the other way round. The choice of the pictograms is a reference to humanity, to the sharing of common space between individuals who live in the same place and agree on their responsibilities. It is a manifesto for a harmonious, nonhierarchical society. In addition, it was important for me to take these pictograms into a physical dimension. If the visitor to the white cube (which is also an allusion to the art system) starts with this room he or she has no problems of perception, seeing the white room at once and recognizing the drawings on the walls. If the visitor comes from the black box, then the experience is different, and the details become apparent only after a certain lapse of time. As their gaze sharpens, viewers realize that they are not surrounded by simple white walls, but by canvases that have been printed and drawn on. A drawing multiplied, printed and partly retouched by hand in ink. Walking on the visual representation of other individuals and different worlds, the viewer begins to ask various questions: can I walk on the work? Will I destroy it? I’m interested in investigating the civil involvement, the reflective attitude of viewers and their subjectivity.

Irena Lagator Pejović, Occupying/Liberating Space and Time, 2005. Photo: Irena Lagator Pejović.

In your works the titles, the meaning and etymology of words, often have great importance. Occupying/Liberating Space and Time, 2005/2013, is a series of photographs telling the story of a space that has a life of its own. What do you want to represent with this ongoing life?

For me language and the etymology of words have a fundamental role. In this case, the title of the work is a step beyond social themes. How could we imagine common space and shared time if our occupation of them were peaceful and poetic? The occupation of space is not just geographical, it is personal too: if we occupy the lives of others with existential questions, we are taking up their time and residing in their space. I’m interested in redefining the role of the citizen in space anthropologically, and changing the nature of the processes of occupation and liberation of space itself. I took these photographs over the course of eight years in a semi-abandoned town in Montenegro. In the windows of the uninhabited space (perhaps an office, perhaps a store) the only remaining form of life was the plants that grew over time. On the outside you can see a layer of gray plaster that had initially been laid on to cover the windows, but that has been removed by the townsfolk, little by little, day after day, to give light and life back to the plants. A simple act, in a small, almost deserted town, that takes on a universal significance. So I decided to return at regular intervals to take photographs of the windows. For this reason I inserted the dates of the pictures in the title of the work, as an indication of the passing of time and the involvement of the inhabitants. The aim was to make freedom of thought and the independence of civil judgment visible. This space shows a peaceful occupation by the plants from the inside, and in parallel a poetic liberation by the people who live outside and take the responsibility of interacting with the space. In this way, as in all my works, the viewer again becomes the protagonist of the work.

Your most recent work, Cinema Abbandonato [Derelict Movie Theater], tackles the question of the loss of the social and spatial relationship with places. What are you trying to investigate with these photographs that portray the desolate life of a movie theatre from the eighties?

Cinema Abbandonato is a photographic installation that shows the run-down state of a former movie theater in the Montenegrin town of Rijeka Crnojevića, the same location as that of my work Occupying/Liberating Space and Time. The theme of the desertion and transformation of the town interests me chiefly from a phenomenological and anthropological point of view: neglect versus cultural development, the exclusion and inclusion of cultures, the construction and deconstruction or reconstruction of the heritage, limited and unlimited responsibility. They are all core themes reflected in the state of this derelict movie theater from the eighties. The four photos form a cube one meter on a side that has been left empty inside. To look at the pictures, the visitor has to walk around the cube, while to discover its contents (or the lack of them) he or she has to go beyond the surface, enter the cube itself and establish a relationship between the space outside and inside. The objective is to make a connection between the passivity of the filmgoers who once frequented this movie theater and the interactivity of those who experience this space today with a new responsibility. Starting out from the discourse on space and time I therefore end up asking myself existential and cultural questions.

Irena Lagator Pejović, Own Space, 2006. Photo: Michael Schuster.

Irena Lagator Pejović, The Society of Unlimited Responsibility, 2006. Photo: Irena Lagator Pejović.

Irena Lagator Pejović, Further than Beyond, 2013. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

Irena Lagator Pejović, Ecce Mundi, 2013. Photo: Dario Lasagni, Lazar Pejović.

Irena Lagator Pejović, Please Wait Here, 2005. Photo: Aldo Mela.

Irena Lagator Pejović, Abandoned Cinema, 2014. Photo: Irena Lagator Pejović.