20 July 2017

For Francesco Vezzoli the past is a mine of wonder and radical gestures, a mythological backdrop of truth and aspirations to be placed at the service of contemporary society. In his most recent mise-en-scène, the artist has produced not a work, but an entire exhibition devoted to the most controversial and unresolved years in Italian history, the ones from 1968 to 1980, recounted through the filter of the Italian broadcaster RAI and selected works of art that he has arranged in three chapters—art, politics and entertainment—in the spaces of the Fondazione Prada in Milan. In a powerful recollection that intertwines irony, glamour, kitsch, ambiguous personalities, interrupted liberations and never forgotten illusions, Vezzoli invites us to rediscover the fresh and alluring fascination of an emerging mass culture at a moment in which anything was possible, and a great deal actually happened.

TV 70: Francesco Vezzoli Looks at the RAI is not a monographic exhibition on your work, but the story of a moment in cultural and social history mediated by the public TV broadcaster and distilled by your own gaze. Can you tell us something about its origin?

It is a long-term project, and embraces everything I’ve always loved. I’ve waited years for the opportunity to carry it out, and at a certain point I was afraid that someone else would get there before me. After all, the art industry is on the rise and if the number of institutions is growing it is also necessary to diversify what is on offer, to go beyond Matisse and Picasso. And instead it’s been left up to me, because the right moment has come and because behind me there is the Fondazione Prada, which is anarchic and visionary.

View of the exhibition TV 70: Francesco Vezzoli guarda la Rai, Fondazione Prada, Milan. Mario Schifano, Paesaggio TV, 1970. 9 artworks. Photo: Delfino Sisto Legnani and Marco Cappelletti. Courtesy: Fondazione Prada.

A right moment that coincides with the crisis in traditional television. Do you think the solution lies in looking at the models of the past?

The crisis in television does not concern television in itself, but the digital revolution, the fact that the mode of use has changed completely. The television of those years was like a Solemn Mass and as such it created myths. It was a ritual and people were attached to its idols; not in a hysterical manner, because it wasn’t rock ’n’ roll, it was “home.” How do you create a home? You have to do it in such a way that people want to come back to a place at a certain time to see and listen to a particular person, stimulating a process of affection-building. None of this exists any longer and it won’t be coming back, just as videorecorders and DVDs won’t be coming back. Now we live on digital platforms: someone watches Montalbano at nine in the evening, someone else at three in the afternoon. TV programs no longer have fixed times.

A program like Milleluci had 30 million viewers. Is this the hub of the exhibition?

Yes. Milleluci could be the cultural and social equivalent of a show watched by 90 million people in America. The Italian television of those years was entertainment for the masses, which is a very difficult thing to produce, especially in non-totalitarian regimes. What comes to your mind when I speak of entertainment for the masses? Girls in uniform spinning hoops, propaganda, and Mussolini looking on smugly, no?

And yet the nascent public service broadcaster did not think entertainment had a political dimension, and Milleluci was hosted by two women, Mina and Raffaella Carrà. An error of judgment?

All churches—be they political, ideological or religious—find it hard to adapt to technological revolutions. We had the revolution of radio, then that of television and now we are going through the digital and computerized one. Now even the pope has to tweet. Women, who are by nature more pliant, even intellectually, were inserted into the segment of power that was the TV of the seventies, when someone thought they might be a nice bit of decoration. But the puppy was a pointer, a spearhead, not a lapdog.

View of the exhibition TV 70: Francesco Vezzoli guarda la Rai, Fondazione Prada, Milan. Renato Guttuso, La visita della sera, 1980. Photo: Delfino Sisto Legnani and Marco Cappelletti. Courtesy: Fondazione Prada.

And how has the artist Francesco Vezzoli, influenced by that ritual experience of the television, adapted to the new dimension of cultural entertainment online and on demand?

By nature I’m a compulsive consumer of culture. I can watch a box set with a season of the television series The Good Wife in five days, then I get emotionally involved in the story and I dream about the characters at night. There is no ritual, there is no schedule. I decide, I enjoy and I suffer. As Francesco Bonami said at the Venice Biennale he curated in 2003, for some time now we have been living in a dictatorship of the viewer. Certainly, you still have to go and see the Biennali and exhibitions, but you watch TV programs whenever you want.

In this connection, you had also worked on another exhibition project with the Fondazione Prada, the Trilogy of Death (2004), inspired by two of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s films, Love Meetings (1965) and Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975). To what extent do these two projects represent different moments in the course of your development , or if you like of your relationship with television, and what connects them?

What they have in common is an exceptional partner like the Fondazione Prada, something that should not be undervalued. On the plane of the contents, however, in 2004 we focused on Berlusconian aesthetics through a classic reality show on couples and the romantic relationships, using famous actresses. This project is the exact opposite: pure philology. We went digging in the archives of the RAI and brought to light everything that was as distant as possible from that that imagery.

With this exhibition you have finally turned your back on the image of the narcissistic artist, seduced by Hollywood and the stage, that accompanied you for many years following works like An Embroidered Trilogy (1997–99) or Marlene Redux: A True Hollywood Story! (2006). The glamour in your work is above all a veil through which to observe society. To what extent do you regard yourself, then, as a political artist?

To what extent I’m not going to tell you, but I’m certainly more political than narcissistic. There are people who think I live in a house adorned with red velvet and the mannequins of Iva Zanicchi’s costumes in Canzonissima, or that I spend the whole day lying on a couch and listening to Vincenzo Bellini’s Norma with tears running down my cheek. It is not so, it’s an image of me that doesn’t match reality. Moreover, if I were so caught up in all this I wouldn’t be able to conceptualize it, to take the right distance. I’ve always tried to explain that putting certain figures on the pedestal of contemporary art is a cultural act, just like the project on the RAI. Seeing the works in which I used my image as an unmistakable sign of my vanity is a great misunderstanding: I play with the narcissism of the art system.

View of the exhibition TV 70: Francesco Vezzoli guarda la Rai, Fondazione Prada, Milan. Michelangelo Pistoletto, Serigrafo bianco, 1963-77. Photo: Delfino Sisto Legnani and Marco Cappelletti. Courtesy: Fondazione Prada.

On the subject of misunderstandings, the exhibition at the Fondazione Prada begins with RAI broadcasts devoted to artists. One struck me in particular: it is a documentary made by Franco Simongini on Giorgio de Chirico in which the great artist paints a sun, but declares that he prefers rainy days; he says that he often uses the car, but you don’t see any in his pictures; he is irritated by autographs, but if he isn’t asked for them feels bad. Is this dichotomy between the man and the artist true for you as well?

Francesco Vezzoli is someone who, having made a thorough study of the glamour and celebrities, knows their dangers. They are moments of great euphoria, but when they vanish they leave an emptiness behind, like love. And emotionally they wear you out, leaving deep and terrible marks. History shows us this. And I think I’m closer to being an expert on stars than a star. And if I were the Roland Barthes of glitter?

At the beginning of your career you worked with embroidery, a means of expression once relegated to the world of folk culture, remote from that of contemporary art. Than you started to make use of TV formats, dressing up as Marlene Dietrich, working with actresses like Natalie Portman, Sharon Stone, Cate Blanchett and Lady Gaga. You’ve always demystified art and its taboos. What has guided you on such a multifaceted and yet consistent journey?

Irony, an unfashionable and undervalued concept today. For me it is extremely valuable, it has something to do with survival. Call it slippage if you will, it is my guiding thread, my attempt to smile at the drama. Gore Vidal told me that if there is a country where irony has always been punished it is America, and the divine punishment visited on us now is to be the country that clings tenaciously to irony in order to bear the present.

You have described television as “the place where you find pure truth as well as its antidote.” Light and shade, therefore. What was it like for you?

There were no alternatives: there was no internet and there were no cellphones, there were no social media. Those who had no direct relationship with the structures of power came to know what was happening in the world from the opening sequences of newscasts.

View of the exhibition TV 70: Francesco Vezzoli guarda la Rai, Fondazione Prada, Milan. Giulio Paolini, Apoteosi di Omero, 1970–71. Photo: Delfino Sisto Legnani and Marco Cappelletti. Courtesy: Fondazione Prada.

In those days the RAI treated artists as public figures, with a social role and a specific educational function. Do you think there has been a parting of the ways between art, society and its representation on television?

Berlusconi has certainly been a game changer. However, I believe that the television of today, with its digital micro platforms, offers even more culture than that of the past, only that the numbers are small. There are far more sophisticated programs than the ones I’ve put on show. Public broadcasting still carries out a cultural service, it’s just that you have to go and look for it. It’s no longer the Centre Pompidou, it’s the State Archives.

What does it change if television becomes a private experience?

In the sixties everyone could see Roland Barthes, Alberto Arbasino and Giosetta Fioroni’s production of Carmen. Television spoke to the masses, but it could allow itself to broadcast high-quality contents or uninhibited ones, like Cicciolina in a state of undress or Amanda Lear in a transgender version. All at dinner time.

What happened, in your view, to that revolution?

Forty years have gone by, and in many ways it has not had the impact people thought it would have. Showing even just fragments of it today stirs emotions. I myself have been moved when I was hugged by women who lived through this story in person. Women who feel betrayed by this so reactionary moment. Perhaps something more was expected from all those battles.

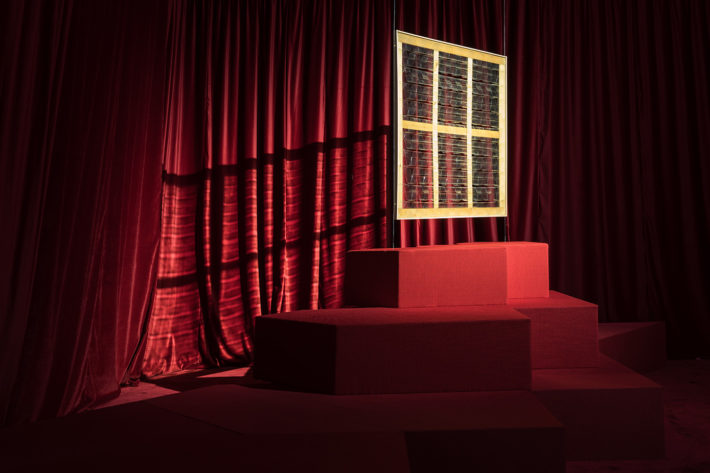

View of the exhibition TV 70: Francesco Vezzoli guarda la Rai, Fondazione Prada, Milan. Photo: Delfino Sisto Legnani and Marco Cappelletti. Courtesy: Fondazione Prada.

Speaking of the masses, what is your relationship with Instagram?

It fascinates me greatly, and I study it under cover. I’m not on Instagram, but I do look at it. I’d never have the courage to post one of my photos, I’m afraid of other people’s judgments, even though I often expose myself in my work. Instagram is a world of perfect bodies, withering quips, it makes me feel inadequate. I look at the others: what wisecracks, what putdowns, what biceps! I’ve not yet succeeded in competing with all this pithiness. But I follow it, and I’m aware that part of the future lies there.

Alongside social media, where do your studies take you?

I drift in history: from Instagram to ancient Rome to the 1970s. In despair, I look at Instagram, a world filled with implausible bodies, and react by plunging into Roman relics and the historical archives. I try to comprehend a present that does not match the one that had been forecast to me, ad meliora. To me it seems more like a continual mise-en-abyme, or perhaps a real abyss.

Are you nostalgic?

No, I like to understand things, I’m not nostalgic. I would like to understand, for example, how physicality is manipulated not just on Instagram, but on Grinder too: all to generate an illusion or a sense of glory. The question is whether there is a reality today, whether there is a desire that goes along with this staging of the body. Are we so dazzled by virtual reality that we no longer see the physical one?

Has this dissatisfaction with the new imagery presented on the social networks stirred in you a desire for a return to the origins?

In a certain sense yes. In a year and a half I’ll be opening an exhibition at the Lambert Collection in Avignon on all the artists who have had the courage to look back to classicism at a moment in history when to do so was politically risky. The starting point is Cy Twombly, and I’d like to go back in time, telling the story of how an imagery has been used politically as a means of propaganda.

View of the exhibition TV 70: Francesco Vezzoli guarda la Rai, Fondazione Prada, Milan. Photo: Delfino Sisto Legnani and Marco Cappelletti. Courtesy: Fondazione Prada.

View of the exhibition TV 70: Francesco Vezzoli guarda la Rai, Fondazione Prada, Milan. Carla Accardi, Casa Labirinto, 1999 – 2000. Photo: Delfino Sisto Legnani and Marco Cappelletti. Courtesy: Fondazione Prada.

View of the exhibition TV 70: Francesco Vezzoli guarda la Rai, Fondazione Prada, Milan. Carla Accardi, Grande trasparente,1975. Photo: Delfino Sisto Legnani and Marco Cappelletti. Courtesy: Fondazione Prada.

View of the exhibition TV 70: Francesco Vezzoli guarda la Rai, Fondazione Prada, Milan. Photo: Delfino Sisto Legnani and Marco Cappelletti. Courtesy: Fondazione Prada.

View of the exhibition TV 70: Francesco Vezzoli guarda la Rai, Fondazione Prada, Milan. Giosetta Fioroni, La spia ottica – Ovvero la mia camera da letto, 1968 (2017). Photo: Delfino Sisto Legnani and Marco Cappelletti. Courtesy: Fondazione Prada.

View of the exhibition TV 70: Francesco Vezzoli guarda la Rai, Fondazione Prada, Milan. Giosetta Fioroni, La spia ottica – Ovvero la mia camera da letto, 1968 (2017). Photo: Delfino Sisto Legnani and Marco Cappelletti. Courtesy: Fondazione Prada.

View of the exhibition TV 70: Francesco Vezzoli guarda la Rai, Fondazione Prada, Milan. Photo: Delfino Sisto Legnani and Marco Cappelletti. Courtesy: Fondazione Prada.