2 May 2013

In response to great demand, we have decided to publish on our site the long and extraordinary interviews that appeared in the print magazine from 2009 to 2011. Forty gripping conversations with the protagonists of contemporary art, design and architecture. Once a week, an appointment not to be missed. A real treat. Today it’s Alfredo Jaar’s turn.

Klat #01, winter 2009-2010.

One of the most radical voices on the international art scene, Alfredo Jaar has been exploring the pervasive character of the ideological manipulation carried out by the mass media for over thirty years. In the interview he has granted to KLAT, the artist talks about the early days of his career under Pinochet’s dictatorship in Chile, about his interest in Africa and about his admiration for the Italian culture of the 20th century. All under the sign of the ethical need to imagine (and create) a better world.

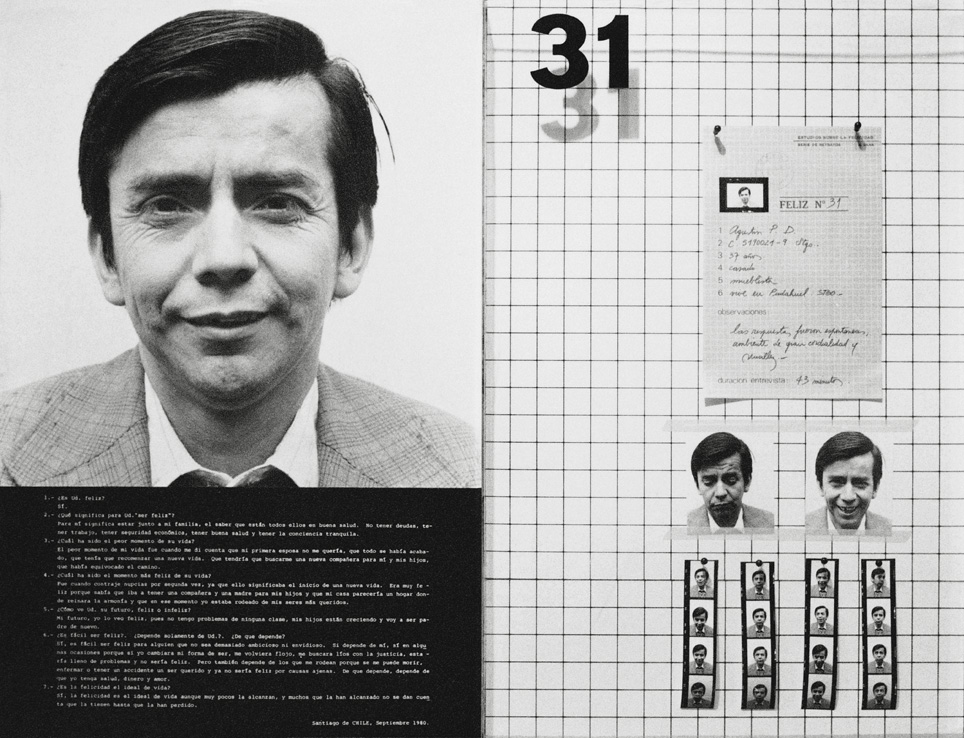

I would like to start our conversation talking about the beginnings of your artistic practice during the 70’s in Chile, your birth country. Once you said that when on September 11th, 1973 the democratically elected president Salvador Allende was overthrown by general Pinochet, with the support of the United States, Chileans had their small 9/11. It seems that your social engagement as well as your political struggle toward democracy originate from the oppression you and all Chileans had to face and endure after that day. Can you tell me more about the milieu in which your first major work Studies on Happiness came about?

The military coup occurred on Tuesday, September 11th, 1973. It was a tragedy of incalculable proportions. It lasted 17 years. For us September 11th became a dark day in our history, and indeed, in the history of the world. When the next September 11th took place in New York in 2001, it was a worldwide spectacle that was displayed simultaneously on TV screens around the world. And from that moment and on, our September 11th disappeared from the consciousness of the world. It was overtaken by an event that had taken place, ironically, in the country that had orchestrated our own tragedy, with Nixon and Kissinger financing the coup from the White House. It is in this context that in an interview I explained that even our tragedy, our September 11th had become “the small eleven”, el once chico as they started calling it in Chile, next to the “big one” in New York. Nevertheless, Chileans endured 17 years of dictatorship, murder, oppression and exile. But as Chile is a small country with no great geopolitical weight, this tragedy developed largely in silence and invisibility. I became an artist during those years of dictatorship. Among other things, dictatorship meant censorship. No one could express overt opposition to the Junta regime without risking being “disappeared”. Artists had to learn how to create, poetically, spaces of resistance. My project Studies on Happiness tried to create not only a space of resistance but most importantly, a space of hope. It was a very ambitious project in seven phases that lasted 3 years. In a country that did not have democratic elections, I invented a poetic, almost philosophical way for people to participate and voice their opinions. I was a young artist, almost fearless. I wish I still had that utopian belief in me today… But I strongly believe that we are the response to all the stimuli we receive. And if living and working in Chile during those years clearly shaped my early career (I left the country in 1982), there are many other stimuli and experiences that have also determined who I am as an artist and why I do what I do.

Alfredo Jaar, Studies on Happiness. Portraits of Happy and Unhappy People, 1980. Courtesy: Galleria Lia Rumma, Milano

Speaking about the intellectual stimuli that informed from the very beginning your art practice, I am thinking of your remarks this year in New York during a lecture held at the Whitney Museum ISP, where you stressed that you probably would have not become an artist if you had not encountered the political and poetic achievements of three major Italian thinkers of the XX century, Antonio Gramsci, Giuseppe Ungaretti, and Pier Paolo Pasolini. It is quite remarkable as a statement, because the three of them do constitute a philosophical legacy which belongs to the intellectual treasures of recent Italian history. Nevertheless they are, Gramsci most of all, rather forgotten nowadays in Italy and their ideas, engagement and struggle seem to interest hardly anyone and do not shape the current civic and political discourse of the country. Although you really wonder if today in Italy there is a civic and political discourse at all. Anyway, how did you get to know their works? Did they nurture the developments of your practice since your early Chilean years?

In Santiago I studied architecture and film. I discovered Italian cinema very early, particularly the neorealist movement. I still remember the shock of watching Rossellini’s Roma Città Aperta and De Sica’s Ladri di biciclette. I was also interested in Visconti, but it was Antonioni that captured my imagination. I wanted to be a poet like him. It was in this context that I discovered Pasolini, both as a filmmaker and a poet. His poem The Ashes of Gramsci directed me to Gramsci’s writings. At the same time, I realized that Gramsci was an important intellectual source for the anti-fascist resistance in Chile. I quickly realized that Pasolini was the model of intellectual I was interested in following. He was the most complete intellectual: a filmmaker and a poet, but also a writer, a critic, a playwright, a columnist, and finally a polemicist, fully engaged with the culture and society of his time. Gramsci’s writings were a revelation: he is in my view one of the most lucid and illuminating intellectuals. His radical political thinking coupled with his formidable cultural analysis are as necessary today as they were in his time. I have always liked poetry and it was Pasolini’s poetry that directed me towards Montale, Saba and Ungaretti. Giuseppe Ungaretti became one of my favorite poets because of the extraordinary economy of means of his writing, his brilliant capacity to say more with less. I never studied art and I still consider myself an architect and a filmmaker. When I am not making films, I actually describe myself as an architect making art. I still use the methodology of an architect to make art. Architecture is a major influence in my practice. But I have also been influenced by many great artists and intellectuals and in some recent Italian projects, you can say that I have been working under the shadow of Gramsci, Pasolini and Ungaretti.

Alfredo Jaar, The Ashes of Pasolini, 2009. Courtesy: Galleria Lia Rumma, Milano

So it is under this shadow that you enforced the idea of the revolutionary potential of cultural experiences, which is at the core of Gramsci’s thought and his belief of how culture can affect change and even bring about subversion within the political realm. This makes me think of your public intervention Questions Questions, part of your large exhibition It Is Difficult at Spazio Oberdan and Hangar Bicocca in Milan, in the fall of 2008. You raised a series of questions addressing the popular understanding of culture and made them visible in the public space as simple placards on public buses, billboards, subway and trams. That way you drew attention to essential although neglected questions, such as Does Politics Need Culture? What kind of reactions did you expect from the general audience of the city? And how did it actually go?

This public intervention was my modest answer to the extraordinary control of the Italian public space by Berlusconi’s media and advertising network. This quasi total control has tragically rendered obsolete the meaning of public space. You can sadly declare that there is no public space in Italy, or almost none. It is an astonishing development that has relegated Italy to the 73rd position in the world regarding freedom of the press (source: Freedom House, editor’s note). This shocking reality was the environment in which I had to work. I decided to try to create little cracks in the system. I tried to occupy every single space available: public buses, subway, phone booths, street posters, billboards, electronic screens, a million postcards, a web site. For three months. If the spaces had not been donated to us, the project would have cost more than a million euros. The questions created a network of resistance in the city, a new space of hope. In terms of reactions, I didn’t know what to expect. I had the fear that people had been completely anesthetized by the Berlusconi system. But reactions were overwhelmingly positive, and we received an enormous amount of answers. We organized a one-day Symposium with a dozen intellectuals, we had full house. La Repubblica did a 4 pages story on the project and asked some twenty intellectuals to answer the questions. Bernardo Bertolucci, Dario Fo, Inge Feltrinelli and Michelangelo Pistoletto participated, among others. I discovered that people had a real, palpable need to express themselves and Questions Questions offered a modest space to do so. In a way, this was my most Gramscian project so far, a clear demonstration of the capacity of culture to affect change.

Moving on from this thrilling project, I would like you to further elaborate on your understanding of culture. In a statement of yours that originally appeared in the book JAAR SCL 2006 and then partly re-published in the catalogue accompanying your exhibition La politique des images, held in 2007 at the Musée Cantonal des Beaux-Arts in Lausanne, you said that, unlike that of media, the world of art and culture, i.e. museums and universities, «is the last place where you are still free to dream of a better world». I fully endorse this opinion and your concern about the ideological manipulation administered in the realm of media and popular culture. In fact, that reminds me of what Theodor Adorno wrote in his Aesthetic Theory, where he states that «art criticizes society by merely existing» and that, in the end, art defines itself as resistance to society. However, both Adorno and Horkheimer, during their exile years in Los Angeles in the 30’s argued that authentic thought cannot survive if it is treated as a cultural commodity and distributed to satisfy consumer demands as it is, even more now, in capitalist society. So how have you been coping with this puzzle within your practice, as an artist working within the commodified gallery system and with museums funded by powerful sectors of monopoly capitalism?

If you look at the history of art, and particularly at the final fate of the avant-gardes, it has been clear that it is impossible to remain outside the system. Even the most radical gestures are recuperated by the system and transformed in commodities. The system always wins. Dada was its victim. Surrealism was its victim. Fluxus was its victim. Arte Povera was its victim. Conceptual art was its victim. The list is long and depressing. In the face of such reality, I have, for the last 30 years, divided my work in three main areas: only one third of my time is dedicated to working within the so-called art world, a network of art galleries, museums and foundations where we address a limited audience which is a very privileged one, a small élite. It is because of this that I have dedicated another third of my time to create what I call public interventions, works that try to address real life issues in places and communities far removed from our little art world. It is a different audience, a different context, another world. Finally the last third of my time is spent teaching, directing workshops and seminars around the world: here I interact with the new generation of artists and intellectuals and I share my experience with them while also learning an enormous amount from them. It is only by working in such a fashion that I feel complete, both as a professional and as a human being. By directly addressing the élite, I may be able to affect change in those that have the power to actually trigger those changes. By working on my public interventions I try to expand the limited outreach of the art world and reach a much larger audience, in a context where I feel much more free and where I can be much more radical, without the normal constraints of institutional spaces. And by teaching I try to lead the new generations towards a more critical kind of practice, one that is responsive to the needs of our times and more particularly to the context in which it takes place. These are young and open minds, and eager to change the world. These three practices belong to the system, but allow me a certain amount of free space where I can experiment with certain radical ideas. As William Blake said, you have to invent your own system if you do not want to be enslaved by another man’s system. I have no illusions and like Gramsci, I am an intellectual pessimist. But also like him, I have an optimistic will. What I ask from myself and of my students is what Pessoa calls a «geography of self-awareness», a finely tuned consciousness that will help us better understand the world. And react to the dire unbalances surrounding us, instead of merely replicating them.

Alfredo Jaar, Questions Questions, 2008. Courtesy: Galleria Lia Rumma, Milano

For me, one of your most impressive projects is The Skoghall Konsthall, precisely because, with all its theoretical and practical insights, it seems to encompass perfectly these three crucial aspects you are engaged with in your work: the problematic role of institutions, the social potential of public interventions and the urgency of a radical art-pedagogy. You provided an ephemeral paper-made Kunsthalle for a small one-company town in Sweden, where they had no culture facilities at all, addressing that way the role of art institutions in the public realm. Then, in spite of the general feelings of the local community, you staged a kind of performance burning the institution down only 24 hours after its opening, in a public intervention to create awareness about the need for culture in our cities. Basically, you succeeded in generating a much debated controversy within the inhabitants of Skoghall. The positive conclusion of this years-long dialogue with the city makes the project a striking example of institutional critique practice. Can you recount what happened?

I was invited to Skoghall, a small Swedish town renown for the paper industry that gave it its birth. Stora Enso, the largest paper producer in the world, has its headquarters there and is the main employer in the city. In my research I quickly discovered the alarming absence of a kunsthalle or major space for exhibitions. I immediately proposed to work directly with the paper mill company instead of using the city funding, as it seemed logical to me that as “creators” of the entire city infrastructure, they had to also offer the inhabitants of Skoghall a place for culture. Stora Enso accepted my proposal and decided to cooperate fully in the design and construction of the first Skoghall Konsthall. Naturally, we built it out of paper produced by the paper mill. I curated an opening exhibition of 15 young Swedish artists, who where invited to respond to a paper kunsthalle in a city known for its paper industry. It was a popular event and the entire Skoghall community attended the opening by the mayor of the city. Exactly 24 hours after the opening we burned it down, and this event was even better attended than the opening. Before the burning, a group of concerned citizens approached me to inquire about the possibility of saving the Kunsthalle. I was thrilled as they had reacted exactly as I wanted. But I insisted in the grand finale I had designed. For me, it was important not to impose the community an institution they never fought for. And burning it was a most dramatic way to illustrate the absence of culture. The following year Skoghall selected its disappeared Kunsthalle as its most significant building. Seven years later I was invited back to Skoghall, as an architect this time, to design and build the first permanent Skoghall Konsthall. I never considered this project as an example of so-called institutional critique. The obvious reason being that there was no institution to start with. Besides I have always found the concept of institutional critique quite problematic. I see this project more as institution-building, in close collaboration with the Skoghall community. In order to accomplish this I had to create that geography of self-awareness I was talking about earlier, and let the community itself come to the realization of its needs.

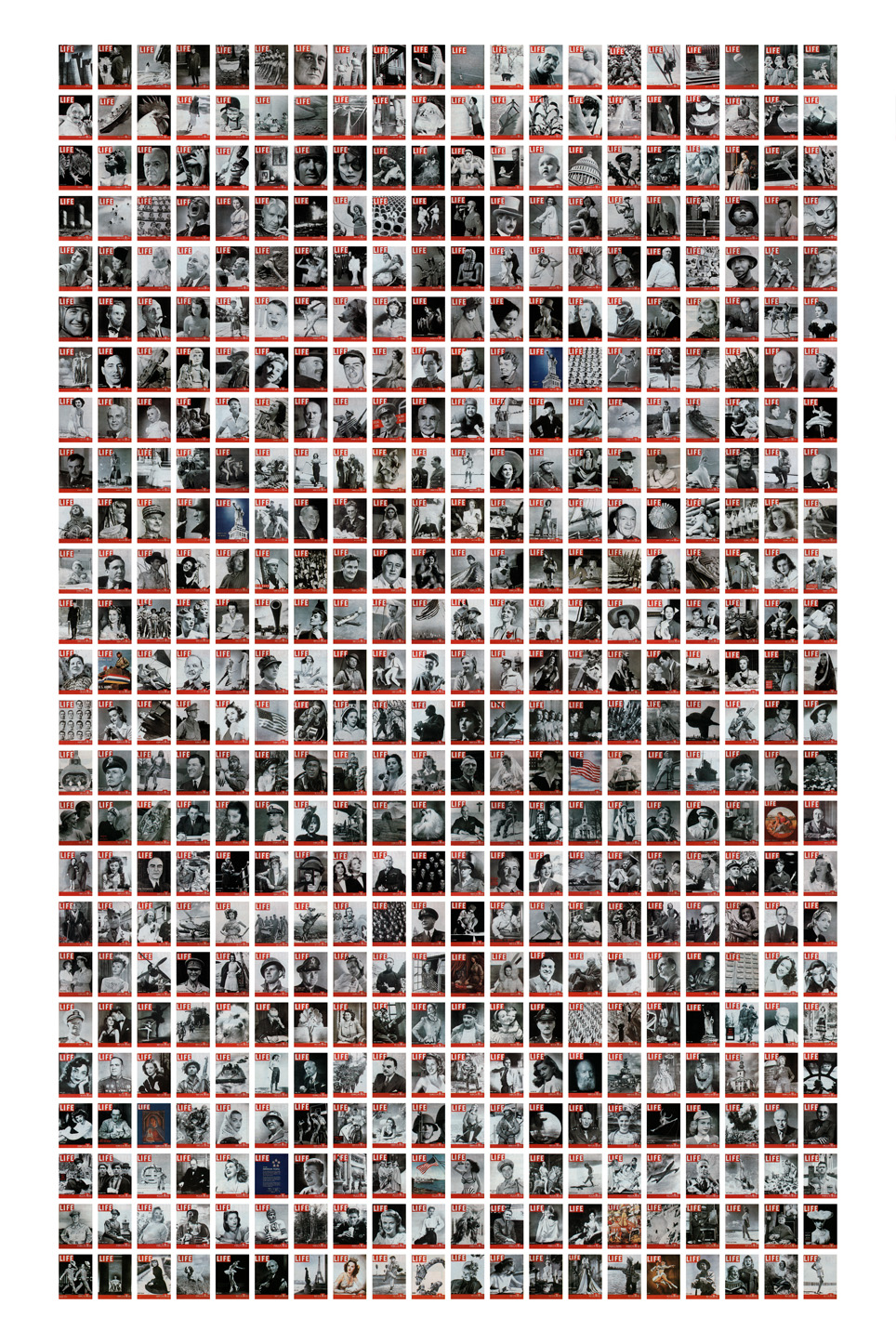

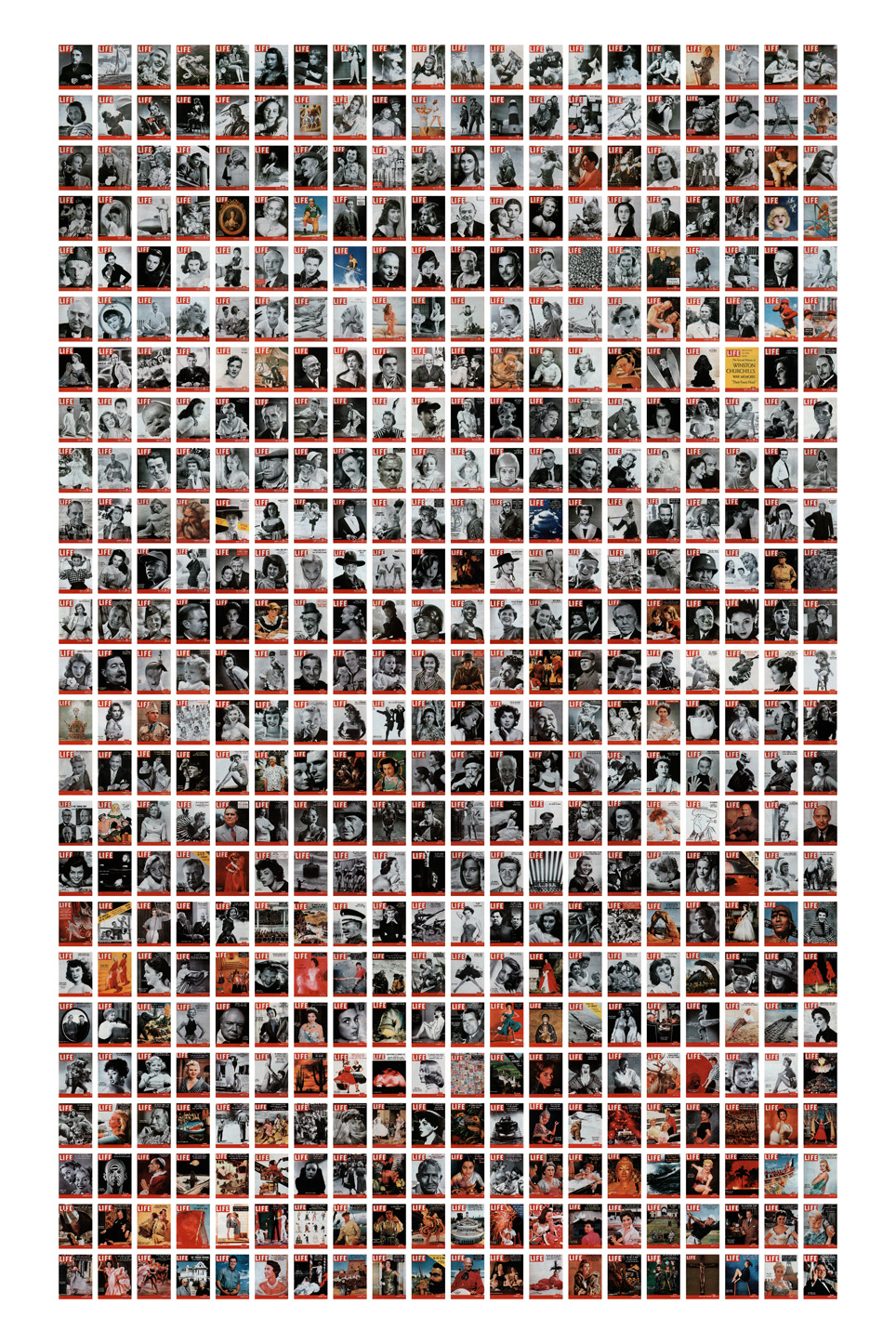

Alfredo Jaar, Searching for Africa in LIFE, 1996. Courtesy: Galleria Lia Rumma, Milano

I would like to know more about your interest for Africa, which is one of the main threads going through your work. I am thinking for instance of the series of projects you developed during 6 years about the 1994 Rwandan genocide. In general, it seems to me that you have been attempting to draw attention to the situation in Africa by unmasking the ideological way in which the media erased the presence of the African continent from our consciousness during the last decades. Your work Searching for Africa in LIFE is a quite clear statement about the role of the media in this regard. By looking at the covers of this popular magazine, one realizes that the subject of Africa comes hardly up, and when it does it is only in terms of animals and wild nature. The social tragedy of the continent is completely ignored, as are other aspects of its reality. How did your research on Africa begin? Do you collect magazines and newspapers on a regular basis?

I am a news fanatic and I subscribe to an absurd quantity of publications. The news media is responsible for shaping our world view, in an uninterrupted, relentless process controlled by communication experts whose objective is to sell us products and ideas. We absorb the messages that they deliver without warnings, without mercy. We might know how to read, but with regards to images we are illiterate: very few of us can decode their true meanings, their silent affect on our consciousness. I have always been fascinated by this process and in my work I have focused on different strategies of counter-balancing the media’s influence of our way of thinking the world. The way most of the media distorts, offends and humiliates the African continent on a daily basis is one of the most shameful, criminal chapters in the history of journalism. It is based on racism, ignorance, prejudice and old colonial habits. It is in my view, an unacceptable reality. The Rwandan genocide started on April 6, 1994. It lasted one hundred days. A million lives were lost. Two million people were made exiles. Another two million were displaced within Rwanda. It took 17 weeks since the beginning of the genocide before Newsweek magazine dedicated a cover to the tragedy. I call this barbaric, criminal, racist indifference. The Rwanda Project 1994-2000 was born as a reaction to this media-crime. I created some 25 projects that were exercises in representation. Futile exercises born out of rage and sorrow. Searching for Africa in LIFE consists of more than 2500 covers of LIFE magazine, from its first cover in 1936 to its last in 1996. They offer us a fascinating glimpse at the values that LIFE magazine believed in and disseminated around the world. They educated Americans. Or misinformed them, by omission and exclusion. We live in a media landscape that has constructed an imaginary image world where African culture, African science, African architecture or African fashion are invisible, or worst, seem to not exist. Media constructs knowledge and it is imperative that we, cultural producers, try to correct the flawed, unacceptable media constructions that we witness every day.

Alfredo Jaar, Searching for Africa in LIFE, 1996. Courtesy: Galleria Lia Rumma, Milano

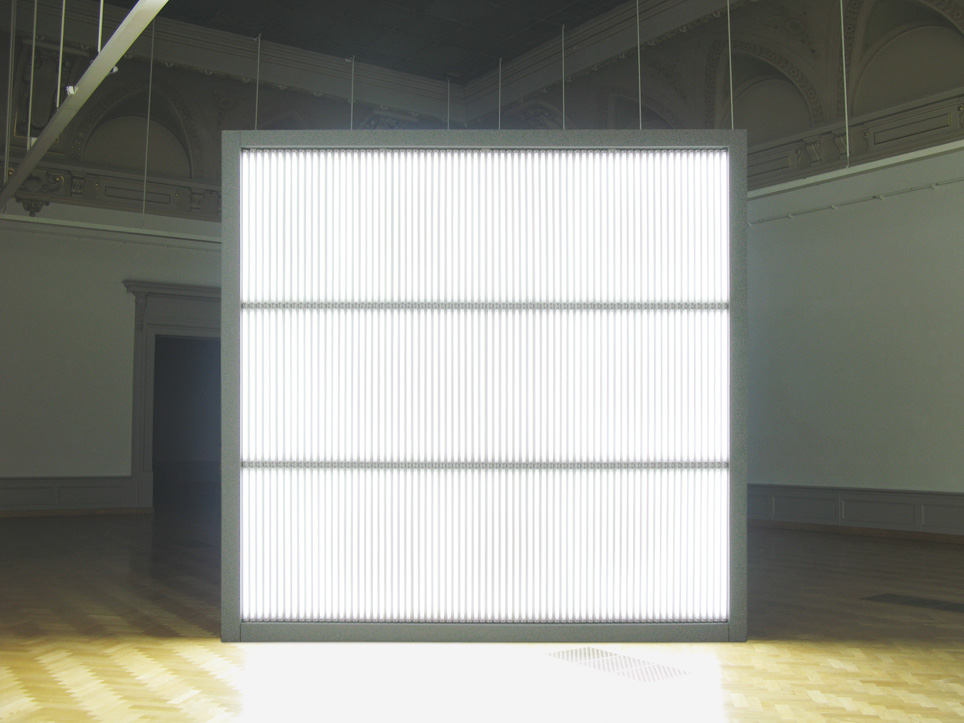

In your most recent exhibition held this spring at Galerie Lelong in New York, titled The Sound of Silence, you recounted through a cinematic format, inside a dark room, the life story of Kevin Carter, a South African photojournalist. Carter won in 1994 the Pulitzer Prize with a photograph depicting a vulture observing a little girl starving in a desertified area of Sudan. Carter was heavily criticized on an international level as a “vulture” himself for not having helped the little girl. As a consequence of that extraordinary image and his distressing professional life, Carter committed suicide. You staged his life story in an extremely synthetic and direct way, with a sort of crescendo, till the point where four flash lights blind the viewers, giving them the feeling of being photographed themselves. Experiencing that work, I think it is impossible not to perceive a strong sense of discomfort and dismay. Nevertheless, it conveys an intense statement on humanism, a kind of hope for the capacity of human beings to testify about their time, to make things visible and eventually act. In the end I see it as a political statement, a call for personal responsibility.

The Sound of Silence is a theater built for a single image. Perhaps, the most extraordinary image ever taken about famine and a world out of balance. In this work it was my intention to explore the ethical as well as the aesthetical questions about the making of an image. And confront the audience, in a clear and direct way, with the fundamental issues that we face as artists when we try to represent the world. We actually never succeed. Because reality cannot be represented. We can only create new realities. These realities are models of thinking the world. The Sound of Silence is a model of thinking the process of image-making. I have always felt incredibly privileged to be an artist. But I have also always felt that this privilege comes with a responsibility. The responsibility to respond to the context and conditions in which we live, or in which other people live. To respond with poetry. To respond with art. To respond with culture. We are free not only to dream a better world, but also to create it. We are creators of models of thinking the world. That is what we do as artists. We create models and throw them to the world. These models, the most successful ones, have a life of their own and are unstoppabble. They exist on their own and affect the way we see the world, affect the way we live the world. It is difficult. Very difficult. It is an almost impossible task. But I cannot imagine a greater privilege and a greater responsibility than this.

Alfredo Jaar, Questions Questions, 2008. Courtesy: Galleria Lia Rumma, Milano

Alfredo Jaar, The Ashes of Pasolini, 2009. Courtesy: Galleria Lia Rumma, Milano

Alfredo Jaar, The Skoghall Konsthall, 2000. Courtesy: Galleria Lia Rumma, Milano

Alfredo Jaar, Searching for Africa in LIFE, 1996. Courtesy: Galleria Lia Rumma, Milano

Alfredo Jaar, The Sound of Silence, 2006. Courtesy: Galleria Lia Rumma, Milano