19 June 2018

Ten years have passed since Nicolas Sarkozy, president of the French Republic at the time, launched the monumental project of Grand Paris, with the aim of redrawing the boundaries of Paris, turning it into a megalopolis of modernity, a global city able to vie with New York, London and Tokyo. And despite the inevitable delays and rises in cost estimates, the largest urban revolution that France has undergone since the times of Napoleon III and Baron Haussmann is making good progress. New economic powerhouses and forms of transport, university centers of excellence and cultural spaces of the 21st century, regeneration of the outskirts and “sensual” train stations, sustainable districts and futuristic buildings, grandeur and foresight, combining an improvement in the living conditions of the city’s population with a reduction in geographical inequalities: this, in a nutshell, is what is contained in the scheme of urban development that is going to revolutionize the aesthetics and the everyday existence of the Parisian agglomeration by 2030. To get a better grasp of the ambitions, the scope and the challenges of the chantier du siècle, as it has been dubbed in France, we need to start out from a figure: 2.2 million, that is the number of inhabitants of Paris intra muros, a geographical and human entity bounded by the périphérique, the orbital that rings the capital and separates it from the banlieues. On the basis of this figure, the Ville Lumière comes at the bottom of the list of the world’s major cities in terms of population, far below Shanghai with its 24 million inhabitants, but also behind Berlin, Madrid and Rome, with populations of 3.48, 3.17 and 2.88 million respectively. And yet, if we add to the twenty arrondissements into which the French capital is subdivided the municipalities of the so-called Petite Couronne (“Little Crown”), formed by the three neighboring départements of Hauts-de-Seine, Seine-Saint-Denis and Val-de-Marne, the number of inhabitants rises to 7 million, not far off the 8.6 of Greater London, the administrative entity that comprises London and its boroughs.

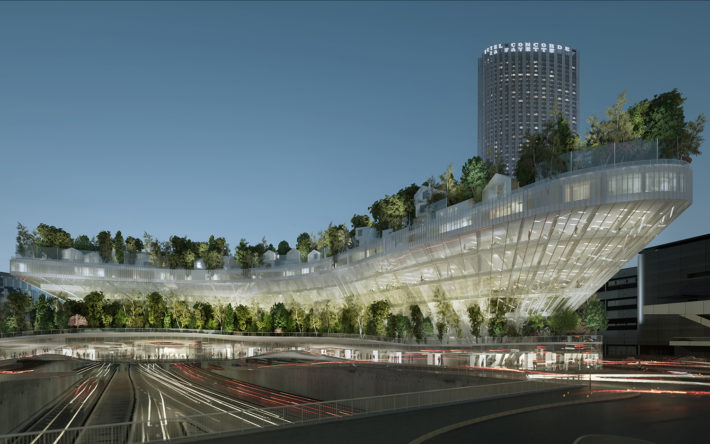

Forêt Blanche, project by Stefano Boeri Architects. © Stefano Boeri Architects.

This is how Sarkozy imagined it in 2008, when he entrusted ten international teams of architects, including Bernardo Secchi’s Studio 09, with the task of reflecting on an “exceptional project” within the framework of the multidisciplinary consultation process entitled Le Grand Pari(s)—which stands for Greater Paris, but also for Big Bet, or pari. And it is for this reason that the Métropole du Grand Paris, the new institutional entity that has taken the place of all the preexisting structures for intermunicipal cooperation, was set up on January 1, 2016, bringing Paris, the hundred and thirty municipalities of the Petite Couronne and seven more municipalities of the Grand Couronne that surrounds the French capital (comprising the départements of Seine-et-Marne, Yvelines, Essonne and Val-d’Oise) under the same administrative umbrella. From the economic viewpoint, the area of Grand Paris, beating heart of the Île-de-France region, is the strongest in Europe. And from the architectural viewpoint it aspires to become, within the next ten years, the epicenter of modernity and innovation. “Thanks to Paris, France has a fantastic advantage that not all countries share: the biggest European economy, Germany, does not have a ‘global city.’ In this context, the absence of major construction sites was in my view a sign of decline. I have traveled all my life. And I’ve never accepted this fact: when I went to foreign capitals, I saw cranes, building sites and work going on everywhere, then I returned to France and saw nothing. That’s where the shock came from! When a country constructs and embarks on new projects, it is undergoing a revival. When it stops building, it is in decline. It is in this sense that Grand Paris should be understood,” explained Sarkozy in an interview granted to the newspaper L’Opinion. In it, the former president illustrated his idea of a “global city.” “It is a city in which there is a unique meeting between economics, history, culture and mythology. In the expression ‘global city,’ there is a mystical, mythological dimension.” And he added: “It is the second motive that has prompted me to desire a Grand Paris, a fundamental motive, in my eyes: when one thinks of the city, one always thinks of technology, of questions of budget, of institutions, but too rarely of architecture, of quality of life and of that word which I consider very important and which has unfortunately disappeared from the political vocabulary, beauty.”

La Cour Verte, project by Stefano Boeri Architects. © Stefano Boeri Architects.

To reorganize Paris and its suburbs in the name of beauty and harmony, Patrick Ollier, president of the Métropole du Grand Paris, launched in 2016 the largest consultation on urban development in Europe, which has seen the participation of 153 multidisciplinary groups: “Inventons la Métropole du Grand Paris.” A consultation based chiefly on private resources (7.2 billion euros of investments for 2.1 million square meters to be reinvented, with 14,000 new housing units to be constructed for around 27,000 inhabitants), in which the redevelopment of entire districts of the city has been entrusted to international teams of architects, in collaboration with local public bodies. The 51 ideas selected for the modernization of 55 urban sites located on the outskirts of Paris include Stefano Boeri’s Fôret Blanche, the first Vertical Forest in France that will be built to the east of the metropolitan area, at Villiers-sur-Marne, and will house residences, offices and commercial premises amidst its greenery. Working with Boeri on the maxi-project of innovative and sustainable development entitled “Balcon sur Paris” there will be, among others, the Japanese practice Kengo Kuma & Associates, which will redesign the congress center at Villiers-sur-Marne, and Manal Rachdi’s OXO Architectes, which will realize together with Sou Fujimoto “Le Potager de Villiers” [The Villiers Vegetable Garden], an area in which over 60% of the structures will be built of wood. The urban revolution of “Inventons la Métropole du Grand Paris,” with its objectives of large-scale transformation of the city and reduction of the costs borne by the community, has been able to attract some big names in international architecture, from Snøhetta to Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners, from Castro Denissof Associés to Dominique Perrault, as well as more recently founded French firms like Des Clics et des Calques and Encore Heureux. The fascination exerted by the diverse range of sites made available, as well as the ample room for maneuver provided by the dimensions of these urban places to be redeveloped, have certainly played a central role in catching the interest of the studios. And by the end of next year, if the timetable is adhered to, we will also know the winners of the second maxi-consultation, “Inventons la Métropole du Grand Paris 2,” who will have had to focus on the themes of smart housing, energy transition and nature in the city to shape their development plans.

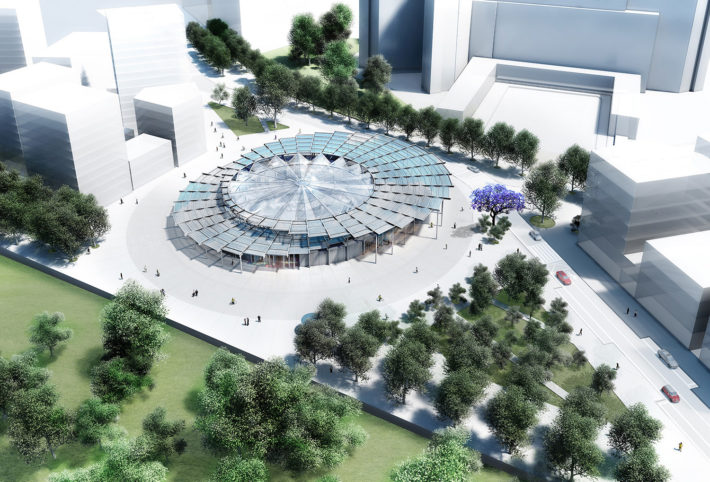

Gare Clichy-Montfermeil, Seine-Saint-Denis (line 16), project by Miralles Tagliabue EMBT and Bordas+Peiro. © Miralles Tagliabue EMBT, Bordas+Peiro, Société du Grand Paris.

In parallel to the dynamism of Ollier and the Métropole du Grand Paris, the municipality of Paris, with Anne Hidalgo at its head, launched in 2017 the second stage of the competition Reinventer Paris—whose finalists were selected in March of this year—with the goal of constructing “the innovative, sustainable and supportive city of the 21st century.” “[W]e are rejecting a Paris fossilized by nostalgia or, conversely, drowned in a contemporary movement towards standardization. By opening up the scope of possibilities, by articulating urban, ecological and democratic revolutions, we are going to fashion the City of tomorrow: an open, decompartmentalized, vibrant and radiant place,” the mayor has written on the official website. Twenty-two projects have been selected for the first part of this scheme of urban regeneration, all centered on the concept of green building: they range from green roofs to bio-façades, passing through smog-eating concrete and aquaponics. Outstanding among the winners is certainly Manal Rachdi and Sou Fujimoto’s project “Milles Arbres,” which will see the light by 2022 in the 17th arrondissement of Paris, right on the city’s edge. Rachdi and Fujimoto have imagined setting a forest of a thousand trees inside a structure in the form of a boat, which will have a “house of biodiversity” run by the French Society for the Protection of Birds on its roof. “The underlying concept of our project is a new way of living in an urban environment which intimately combines nature and architecture in a special way. This particular site, on the ring road, is like the last border of Paris. Therefore I think it is the best location to show how Paris can create a new lifestyle for the 21st century, where the integration of nature and architecture will be a major theme. ‘Mille Arbres’ is to me like a dream, a floating village in the middle of a forest […]. I believe that this could be […] the symbol of New Paris,” Fujimoto has explained.

Centre Culturel Dédié au 7è Art, EuropaCity, project by UNStudio. © UNStudio, Flying Architecture.

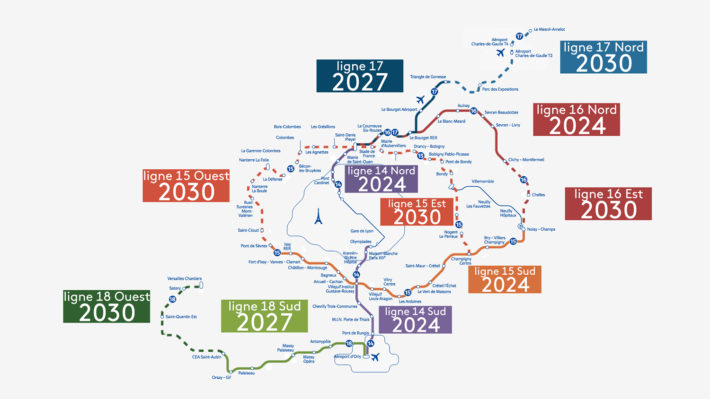

This reinvention of the French capital, which is going to provide 1341 new housing units between now and 2030, also envisages the transformation of the former Masséna railroad station into an “ecological tower of Babel,” as imagined by the DGT architecture studio, and an urban farm of 4000 square meters conceived by Jacques Ferrier and Chartier Dalix, on which co-working spaces, a school of urban horticulture, stores and even the first crop of Parisian tea will spring up. “Reinventer Paris 2,” the aforementioned second phase of the competition organized by Hidalgo, concentrates instead on the subterranean parts of the city, with the idea that these unusual, and often forgotten underground locations have in reality a great appeal and the potential for transformation into places emblematic of modernity. Thirty-four sites have been selected, including the tunnel under the Tuileries Garden and the subterranean passages of the Pont-Neuf, and the eighty-five finalists still have the whole summer to refine their plans and hope for victory. But now we come to what at bottom represents the hub of the Paris of the future, the pillar around which the chantier du siècle has been constructed: the Grand Paris Express, the group of rapid transit lines that will envelop the French capital, permitting an improvement in the connections between Paris intra muros and its outskirts, relieving traffic congestion and stimulating the economic development of the more disadvantaged zones. With 205 kilometers of new lines and 68 stations, the Grand Paris Express, constructed by the Société du Grand Paris (SGP) in collaboration with the transport authority of the Paris region, Île-de-France Mobilités, will double the current length of the Metro. The four new lines, fully automated and forming a ring, 15, 16, 17, 18, together with the extension of two existing lines, 11 and 14, will carry two million passengers every day and improve communication between the major economic, cultural, technological and air transport centers that surround Paris. In detail: line 15 will provide a rapid connection between the three départements of the Petite Couronne; line 16 will permit a better insertion of the northeastern part of Paris, an economically and socially troubled area; line 14 will allow people to quickly reach Charles-de-Gaulle airport, to the north of the capital, while line 17 will do the same for that of Orly, located to the south; line 18, finally, will have the objective of bringing the technological center of Saclay out of its isolation in the southwest of Paris, where President Macron and his government want to establish the French Silicon Valley.

Mille Arbres, project by Manal Rachdi OXO Architectes + Sou Fujimoto Architects. © Manal Rachdi OXO Architectes + Sou Fujimoto Architects.

Yet there is a far from negligible problem of funding. The cost of the work, initially estimated at 22 billion euros, is now verging on 35 billion. For this reason Macron appears to be thinking seriously about speeding up, without exaggerating, the project of the Grand Paris Express, in part because the Olympics are going to be held in the city in 2024, an event that will require a lot of funds and one for which France wants to be sure that the preparations will be perfect. Thus the uncertainties over the final bill will not change the substance of the project, which places at its center the station, conceived as a space of meeting and life, and not just as a place where you take the train. “The station is on the front line for the transformation of the city […]. We have imagined it as a landscape, an efficient and technological one of course, but also a place where the technology will be able to do a disappearing act and leave room for other sensations,” explains Jacques Ferrier, the architect who is coordinating the design of the stations of the Grand Paris and the man who invented the concept of gare sensuelle. A station that is no longer a cold and impalpable place, but a “sensual” space, constructed in accordance with a logic of continuity with the outside and an identity shaped in the likeness of the place in which it will be built. “Developing the concept of sensual station, Jacques Ferrier’s response takes an innovative, creative and forward-looking view of the station of tomorrow. This vision turns the station into an experimental laboratory of contemporary urban life, a space where new ways of being and living together will be tried out. In addition, it inserts it as a public space perfectly integrated into the city, one that will again become an urban point of reference,” wrote Étienne Guyot six years ago, when he was president of the SGP, explaining the choice of Ferrier. In the upper echelons of the République, given what is at stake, talk of the Grand Paris is in measured tones. “This project constitutes a source of immense hope and must not become the cause of immense frustration,” the French prime minister, Édouard Philippe has declared, pointing out that there will inevitably be delays for technical and financial reasons, but that the project will, come what may, be completed by 2030 as planned.

Hôtel de luxe, EuropaCity, project by Atelier COS. © Atelier COS, EuropaCity.

The future of the Île-de-France depends on the realization of this great metropolitan serpent, which will make the life of the outlying districts more dynamic, allowing their inhabitants to travel in just a few tens of minutes from Luc Besson’s Cité du Cinéma, in Saint-Denis, to EuropaCity: 80 hectares devoted to culture, recreation and commerce designed by the Danish starchitect Bjarke Ingels that will spring up near Charles-de-Gaulle airport in 2024. Finally there is the project of regional communication between Grand Paris and Le Havre, the biggest port in France and the maritime front of the French capital. “Grand Paris will clearly have to be organized around a main axis: the Seine. In all the architectural projects, the Seine is central and I’ve never imagined Grand Paris limited to the Île-de-France,” Sarkozy told L’Opinion, before adding: “Look at the city’s coat of arms: you will see a sailing ship that reminds us that Paris has a port, Le Havre. If we separate Paris from its maritime dimension, we separate the city from its economic driving force. Our ‘global city’ begins at Le Havre. From here, it can extend its influence to the south, north and east of Europe.” It is up to Macron, now, to turn these dreams of grandeur into reality.

Grand Paris Express, map of the future Metro system. © Grégoire Courtois, France 3 Paris.

Gare Pont de Bondy (line 15 Est), project by BIG and Silvio d’Ascia. © BIG, Silvio d’Ascia, Société du Grand Paris.

Station Villejuif Institut Gustave-Roussy (lines 14 and 15 Sud), project by Dominique Perrault Architecture. © Dominique Perrault Architecture, Société du Grand Paris.

Saint-Denis Pleyel Emblematic Train Station, project by Kengo Kuma & Associates. © Kengo Kuma & Associates, Société du Grand Paris.